Editors’ note: Like many others on campus, we have dear friends who, as victims of sexual assault, have been ill-served by their University. We believe that the University’s mechanisms for responding to sexual misconduct can be substantively improved, and we are confident that in responding to the complaint to the Department of Education under Title IX, the University will become a safer, better place for students of both sexes. Ann Olivarius was a plaintiff in the 1977 case Alexander v. Yale. Even though the suit was all but thrown out, the plaintiffs succeeded in establishing a precedent that forced schools around the country to adopt policies to address sexual harassment. We asked her for her perspective on the complaint and on the history of sexual misconduct at Yale. —Max Ehrenfreund and Jacque Feldman

…

As a Yale undergraduate, I was one of the plaintiffs in Alexander v. Yale, in which a group of students sued the University after it refused to create a centralized grievance procedure for sexual harassment. Now, when such mechanisms are nearly universal in businesses and universities, the objective seems uncontroversial; even then it seemed reasonable. But Yale fought the idea tooth and claw.

Initially, we did not intend to sue. In the spring of 1977, I led a group in preparing a report to the Yale Corporation on the status of women at Yale after one decade of coeducation. When we surveyed female students, we began to hear a steady drumbeat of complaints about professors who had pressed for sex in return for better grades or access to high-level courses and in some cases fondled or raped students. It was a “dirty” problem, one nobody wanted to talk about—but the women to whom this had happened were deeply upset, ashamed, traumatized. Many of the professors involved were flagrant repeat offenders, but because no one talked about their offenses, female students kept signing up for their classes. Institutionally, there was no central system for collecting complaints. If the student actually worked up the courage to tell her residential college dean or master, the usual reaction was to express sympathy, but to advise her that this was “all part of life.”

We asked Yale to introduce a central grievance mechanism. The University said it would study matters, made sympathetic noises, and strung things along until those who had been pressing for reform were about to graduate; then it refused to act. Hours before my parents were due to arrive for graduation, University Secretary Sam Chauncey, with whom I had been meeting almost every week for three months on friendly terms, called me to say I was about to be arrested for libeling one of the most notorious offenders—Keith Brion, a professor of music and band director, who had assaulted multiple students and raped at least one—by reporting him to the Yale authorities. You actually can’t be arrested for libel, but I hadn’t gone to law school yet, and I was alarmed. I asked him if Yale was going to provide me with legal help. “No,” he said. “We’re supporting Keith.” Yale knew how to play hardball. Its deputy director of public affairs, Steve Kazarian, told a reporter from Time Magazine that I was flunking out (I graduated summa, a soon-to-be Rhodes Scholar) and was a lesbian (I’m glad for people who are, but I’m not).

So we went to court, asking not for compensation but for a comprehensive reporting system. We pioneered a new legal approach, arguing that the pattern of sexual harassment and assault that we experienced as female students hurt our access to education and constituted sexual discrimination, putting the University in violation of Title IX. To give some idea of how far our society has come, this case was one of the first to utilize the concept of “sexual harassment.” The book by prominent feminist legal scholar Catharine MacKinnon that would formally define the term was still a manuscript. We argued in our complaint, “Failure to combat sexual harassment of female students and its refusal to institute mechanisms and procedures to address complaints and make investigations of such harassment interferes with the educational process and denies equal opportunity in education.” That last sentence could have been lifted out of the Title IX complaint lodged this year.

Because this was a brand-new field, we had obstacles to overcome that today’s complainants will not: We had to argue that students had standing to bring a suit under Title IX (that is now established); we had to demonstrate that sexually assaulted and harassed women could represent a “protected class” rather than a collection of individual incidents (they can now); and we had to show how a consistent atmosphere of sexual harassment could impact the educational attainment of women (these days, that’s a gimme). The environment in the 1970s may also have been marginally harsher toward outspoken women. Keith Brion stalked me at night as I was cleaning dorm rooms to prepare for reunions. I reported this to the administration; his behavior did not change, and he kept his job. His wife LaRue was the secretary of my college master, and she threatened to tamper with my file and scholarship applications. I received letters containing death threats, a used condom, defaced pictures of naked women, and a knife.

Our suit was thrown out on technical grounds. Mostly because all of the plaintiffs had graduated, we were found to be ineligible to bring suit, and one woman was found not to have a “quid pro quo” case because the sexual proposition she endured from a male professor did not actually result in a better grade. However, our legal argument was upheld and found wide acceptance in subsequent cases. In the next five years, hundreds of universities across the country instituted grievance procedures.

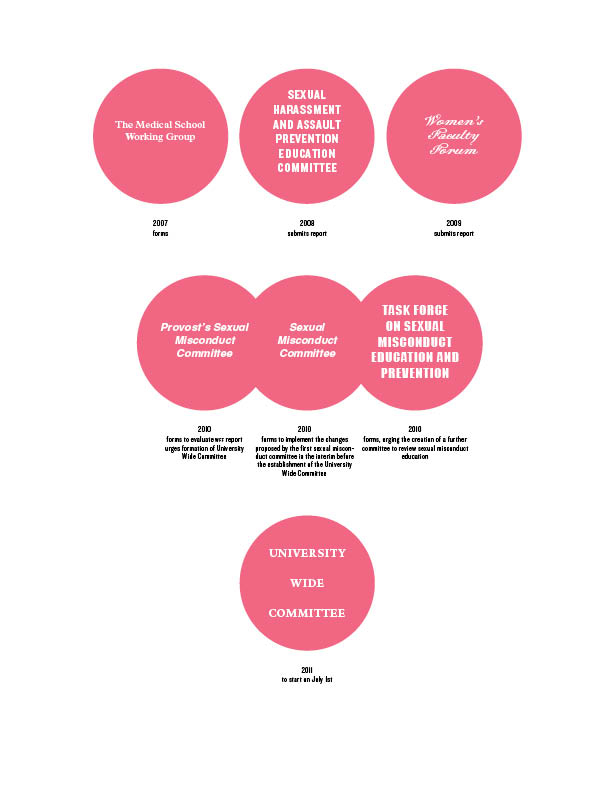

Yale itself created the Sexual Harassment Grievance Board. We thought that the problem was ignorance about harassment and assault and their effects, and so a reporting system would be enough. Yet as with many other confident expectations of the women’s movement, progress has been slower and more ragged than we expected. We were right that ignorance was the problem, but every new generation of women and men, it seems, must relearn fundamental notions about how to treat each other equally.

To its credit, Yale has evolved dramatically since 1977. When I go back to the University, speakers introducing Alexander v. Yale celebrate the plaintiffs, cheerfully glossing over its place on the wrong side of history. By claiming those who brought this landmark case for its own, Yale continues its tradition as the proud alma mater of unconventional thinkers who have led social change. Indeed, Yale has produced some of the greatest forces for contemporary women’s rights: Judith Butler, Hilary Clinton, and Catharine MacKinnon, who was a second-year law student when she wrote the legal theory behind our 1977 complaint, to name a few out of thousands. It is in the footsteps of these forward thinkers that I believe the 16 co-signers of this current Title IX complaint now tread.

Today’s complainants, as I understand it, are highlighting two aspects of Yale life that violate Title IX: inadequate response to many incidents where groups of men disparage women in public with chants such as “No means yes, and yes means anal” or by stealing the T-shirts created by victims of sexual assault for Take Back the Night; and a disciplinary system that does not appear to take sexual assault seriously enough. As for the first problem, I understand the frustrations administrators must feel as they try to regulate the activities of drunk young men taking advantage of the tolerant cocoon university life deliberately provides. Nevertheless, it is clear from the reactions to these incidents that many people think that given the great privilege of a Yale education, a little sexual harassment by frat boys in the evening is not something to make into a federal case. In 1977, we, too, were told that the occasional proposition or grope or rape was something we should simply learn to handle. Now the general public has come to agree that sexual harassment is not to be tolerated, and Yale no longer belittles victims’ concerns.

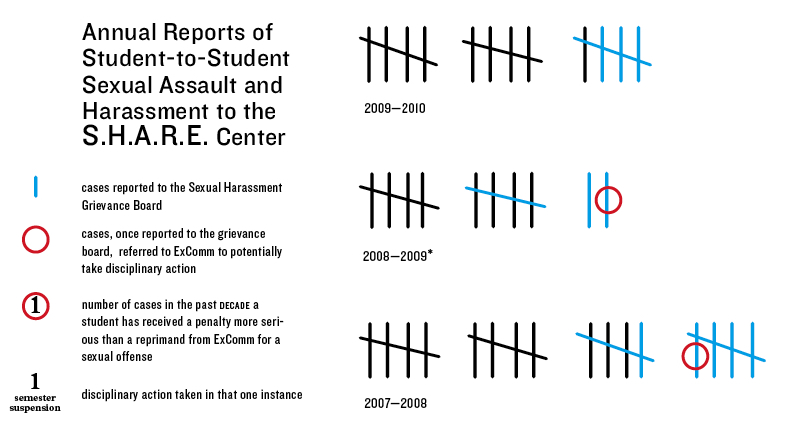

But it does not seem to want to take them seriously either: It often cites a free speech argument in defense of the status quo, claiming that it would not be possible to punish the dirty mouths on campus without risking greater harms. I am not convinced by this. Yale’s own policies impinge on free speech rights in this very area. Students being disciplined for sexual harassment before the Executive Committee must stay silent; whatever incident gave rise to the charge effectively disappears from the newspapers and campus dialogue. No one really knows: who are the perpetrators, who are the victims, how frequent and how serious are their crimes?

As it did in the 1970s, Yale still keeps disciplinary issues fiercely in-house. It counts sexual assaults by Yale students against other Yale students, in buildings where no one but Yale students live, apartment buildings as well as frat houses, as exempt from Clery Act reporting because they are “off campus.” Yale’s disciplinary and counseling systems encourage women victims of sexual assault to pursue their cases internally. Private resolution saves the University lots of bad press. Confidentiality may have advantages for many women, but for others, living on the same campus as their assailants, who are punished lightly if at all, can be distressing and traumatizing.

Change is often slow, and inertia is powerful. But more can be done. I am encouraged by the announcement of the University Wide Committee, which furthers the Alexander v. Yale plaintiffs’ decades-old goal of a single, campus-wide reporting system for sexual misconduct. Hopefully, this Title IX complaint will accelerate the speed and expand the scope of such action. One potential approach could be a major report on the status of women and the state of sexual harassment drawn up not only by Yale students and staff but also outside experts and observers not dependent upon Yale for promotion. These outsiders could also form the backbone of a standing committee on equality issues, meeting regularly and reporting in public annually, able to hold up a mirror to Yale to test whether its actions are meeting its intentions.

Yale College Dean Mary Miller wrote in her recent e-mail to the Yale community: “I can also say that what I have heard about the substance of the complaint does not reflect the Yale that I know.” I am sure she is sincere. I think the project at hand is fundamentally an educational one, as it was in 1977, to encourage people to reexamine their assumptions, so they see the evidence around them in a different light. I have had two daughters go through Yale, and we have hired dozens of Yalies as legal assistants for our law firm. I regret to say that the complaint does reflect the Yale many of them have known. On the Juicy Campus Web site several years ago, a man who said he was in my older daughter’s college discussed in detail how he planned to rape her, and another commenter compared the “fuckability” of my two daughters. Yale did not defend Juicy Campus, but like the excrement I received in the mail, these anonymous comments were symptoms of the large and complex problem the school still faces from misogyny. It is a problem, one that seriously affects the lives of Yale women and men.

Yale remains one of the best places in the world to get an education and to grow as a person. I am grateful to it, and so are my daughters. But Yale can get better. The University should embrace the complaint as an opportunity to become a pioneer for preventative programming and resources. Yale has the opportunity to be a model of transformation. As it does in many other areas, Yale should aim to lead.

Dr. Ann Olivarius is a 1977 alumna of Branford College and the founding partner of McAllister Olivarius, an international law firm in London.