I was walking down Chapel Street one day two years ago,” Steve Maler explains to me at The Edge Tattoo Parlor, which borders the New Haven Green. “And I thought, ‘I need to get a red star tattooed on my neck.’ So I walked in here, and this guy Jeffrey gave me the star, and we became good friends.”

Steve is 26, white, and remarkably tall and thin. When he walks, he floats, leaning forward a bit and striding slowly. The Adam’s apple on his skinny neck bobs as he speaks. The star on the neck symbolizes nothing; Steve simply thought it would look cool. Indeed it does, while announcing both whimsy and daring: One’s neck, unless it’s very muscled, is a particularly painful place to get tattooed.

When Jeffrey noticed that Steve was always drawing and doodling, he taught him how to tattoo at home. Later, The Edge offered Steve a job, so he happily quit his post at an aluminum factory to become a professional tattoo artist. He’s been at The Edge since last February, and is delighted with his life now: “I love coming to work every day, while I used to hate it.”

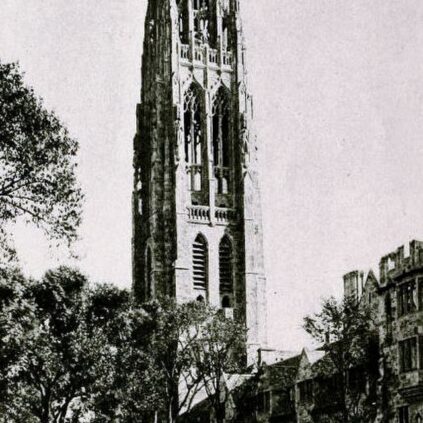

The interior of the large shop is tidy and tastefully decorated, even elegant. Imitation Tiffany lamps hover on various counters, joined by stone gargoyles that recall Yale’s gothic architecture. To the right of the lobby, a corner nook is full of books that offer inspiration for tattoos. The library includes several coloring books featuring pictures of “prehistoric mammals” or “medicinal plants,” the full series of Disney Beginning Readers, Ranger Rick’s Best Friends, The Family Life of Birds, A Handbook of Greek Art, and Lettering and Lettering Display. The lobby and the anterior tattoo area are divided by a counter where I sit and chat with waiting customers. About half the clientèle are walkins, the other half appointments. Often customers come in with their own image in mind, or have an idea of what they want and work with an artist to design it. Others choose from the “flash,” the posters of commercial tattoo designs that hang all over the shop. Behind the counter, the tattoo area itself consists of four stations stocked with the necessary needles, inks, and miscellaneous jars and bottles. All surfaces are gray or black, and look sterile and new. This being the week before Halloween, occasional plastic skulls accompany the vats of vaseline at some of the station.

The Edge, open from 1 to 8 p.m. daily, is a well-run establishment, due in no small part to Tyrone’s management. He’s worked here for almost the full decade the shop has been around. The company owns three other branches in Connecticut and Rhode Island. On Chapel Street, sometimes an artist will barter for a tattoo in exchange for another service. Tyrone explains, “You give me your used car, I give you a $600 sleeve.” (A “sleeve” is a tattoo that covers one’s whole arm.) He continues, “We say we’re pirates—you know, ‘cuz all they did was barter. A little Chapel Street joking thing.”

Like the red star on his neck, Steve’s other tattoos—or “tats”—recall details of his life. He shows me the green flames on his thumb, done by Jeffrey when the two had just become friends. His right arm boasts a bright sun held by a darkly-colored Chernabog, the villain from Fantasia. The sun was done on Steve’s 18th birthday; only recently did Jeffrey give Chernabog some color. “I’m really into the old Disney scene,” Steve tells me. “And late ‘80s, early ‘90s TV cartoons. Have you seen the new image of Strawberry Shortcake? It sucks!”

Around Steve’s neck hangs a red tat of a chain and dog-tag, not an uncommon design. In bubble letters, the tag reads, “Groove is in the Heart.” Steve has to enlighten me: “That’s a Delight song. It just works, because I think music is one of the most important things. I like dancing, too.” His taste in music is eclectic: Beatles, The Cure, Biggie Smalls, Wu Tang Clan, Beastie Boys, Massive Attack, and other electronic and trance music. On Steve’s right calf, a red-headed girl lifts up her shirt to reveal her midriff. This is Steve’s own work: “Eventually I’ll make it really extra-special. . . It’s gonna take a while ‘til I get my own style. What I really want to do is pointillism, shading.” He’d like to take figure drawing classes so that he’s “not just copying cartoons and Maxim and other shit like that.” He’d also like to study photography, learn to use Photoshop, practice piano, take up snowboarding, and draw more.

The first time I met Steve, he gave me his trademark handshake, a four-step maneuver he picked up a decade ago from a friend. He says he uses it “with almost everyone, even old people.” Steve’s girlfriend, Alyssa, confirms: “He acts goofy even with people he doesn’t know.” He makes no pretense of politesse or machismo. He eagerly shows me designs he’s working on for upcoming appointments: a horizontal rose rippling the water it lies on; a nautical star for Alyssa; the elaborately lettered word “MOTIVATION,” surrounded by stacks of cash and marijuana leaves.

While we talk, Jess, the only female artist at The Edge comes over. She is short and tough-looking, often glowering. “Whatcha doin’?,” she asks Steve. “Eating dinner.”

Jess gives him the finger. She later tells me, “Steve and I understand each other. He’s unique. He wears women’s sunglasses— yellow tinted, pink, or sparkly.” Steve loves to sail Frisbees across Chapel Street. He rides down steep hills in a rolly chair. When asked to describe Steve, his close friend Farleigh recites the nonsense sounds “Mao mao mao,” like an incantation, then explains, “This describes Steve’s sense of humor. He’ll just say this when he has nothing else to say. And when he picks up the phone, he’ll say random words or stutter, ‘Hey, hi, hello, hey, hi, hi’… He’s a good guy.” Tyrone, the manager of The Edge, says, “He’s such a calm individual, he’s a pleasure to work with. An old-school tattoo artist would say to me, ‘Who the hell are you?’”

Tyrone, a fit, short 35-year-old black man with several facial piercings and arm tattoos, offers this recent history of the business: “Ten years ago, tattooing wasn’t something to do. Now, I get doctors, lawyers, judges. If you don’t have one, it’s like not having a vehicle. It’s like”— and then he assumes a high, incredulous voice—”‘You ain’t got a car?!’ ‘You ain’t got a tattoo?! Why not?’”

“Old school” tattoo artists come from a lineage of tough guys and troublemakers. Tattooing came to Europe after mid-16th century sailors encountered the art among Polynesian islanders. Later, tattooing was practiced mainly by marginalized groups, such as circus performers, criminals, and French revolutionaries. The first mention of the word “tattoo” in English lies in the journals of the British Captain James Cook, who sailed around the Pacific and spent time with the Tahitians. In 1769, he wrote, “Both sexes paint their Bodys, Tattow, as it is called in their Language. This is done by inlaying the Colour of Black under their skins, in such a manner as to be indelible.” In the Tahitian language, Tattow means “the results of tapping or striking.” Cook’s recording of the word coincided with the rising trend among European sailors, so it stuck.

In the East, like in Polynesia, the custom has traditionally been associated with spirituality; in the West, with subversion. The early Jewish, Christian, and Muslim traditions all prohibited tattoos, and both the ancient Judeo-Christian and Greco- Roman cultures associated tattooing with barbarians, slaves, and the poor. To be tattooed indicated that one was under someone else’s power. Supposedly, the Roman emperor Caligula once commanded all of his citizens to get tattooed, purely for his entertainment. Two thousand years later and halfway around the world, the Patau Islanders in 1832 forced the captured American sailor Horace Holden to endure full-body tattooing. While Caligula’s citizens had no recourse but to oblige their sadistic ruler, back home in New Hampshire, Holden wrote a bestseller about his experience.

Just as being forced to get a tattoo indicates subservience, getting one voluntarily indicates dominance and power. Tattooing, like prostitution, concerns control of one’s body and, by extension, of one’s identity.

In America, the popularity of tattooing has been on the rise since the mid-19th century. Nevertheless, it has been subject to its fair share of scorn. During World War I, the Navy banned tattoos, with the desired result of a healthier crew, and the unintended result of new recruits wearing corsets and camisoles to cover their chest tats. In the 1920s, the conservative, law-obsessed impulse that bred Prohibition prompted many American cities and states, including New York, to outlaw tattooing altogether.

Since the 1980s, American tattoo culture has been shedding its exclusive associations with rebels and bikers. People with tattoos are now as likely to drive a Volvo as a Harley, and artists are as likely to be MFA candidates in need of a job as ex-cons in need of a pay stub.

Today, a tattoo indicates an aspect of one’s identity more than it does rebellion. In the days after 9/11, Tyrone and his crew gave free tattoos memorializing the event. They were overwhelmed the abundance of people, many of whom were first-time tattooees, wanting flags, eagles, the Twin Towers, and even the planes crashing into the towers. “Us Americans,” says Tyrone, “We don’t want to be left out of something, and we want to show our heritage. So we get tats.”

What accounts for this mainstreaming? Perhaps in such an unsettled political climate, people get tats because they offer something permanent in a world in flux. Perhaps Americans love to categorize themselves. Or perhaps people get tats to invite conversation. At least, these are some of the theories academics propose. In the last ten years, as much ink has been spilled writing about tattooing as has been used in tattoos themselves. Not only are there a dozen tattoo magazines, but scholars have pounced on the subject, writing books such as Bodies of Inscription: A Cultural History of the Modern Tattoo Community and Mutilating the Body: Identity in Blood and Ink. There are several country-specific histories of tattooing, and several accounts of the connection between tattooing and the sea-trade. And although tattooing has vaulted into the specialized world of academia, it is a rare Yalie who moves beyond the anthropologic study of a tattoo and actually gets one. Most of the customers at this New Haven parlor, one block from campus, are from outside the University system.

I had feared tough-guy posturing when I first ventured to The Edge, but I do not find much. The second time I come into the shop, Tyrone tells Coniah, one of his main artists, “Be nice to Emily, here.” Coniah, a student at Paire Arts School, seems suspicious but soon warms up. When a customer asks if I am there to get tattooed, Coniah jokes, “We’ll strap her to a chair soon enough.” And Sebastian, a 32 year-old, unusually talented, handsome, and wisecracking artist with whom I had originally met some resistance, adds, “She’s from Yale—they’re sending their spies down here!”

One Wednesday, as I watch Ralph, another artist, tattoo a dragonfly onto the left wrist of a 55 year-old woman, he asks me why I wanted to write about The Edge. Many customers and other artists here have asked me this, and have been intrigued when I’ve told them, “I wanted to explore the tattoo world because it’s totally foreign to me.” I have been flattered when customers have assumed I am there to get a tattoo myself. Really, me? Thank goodness, I don’t look like a total square! But I should not be so flattered: Anyone might get a tattoo these days, even a 55 year-old social worker with big glasses and a grandmotherly haircut. Ralph is not intrigued by my answer; he is indignant: “You think this is the tattoo world?! It used to be guys on Harleys. This is the way the industry is going—it’s Starbucks, it’s mainstream.”

As the industry has grown, there have been more and more tattoo conventions across America, at which renowned artists give custom tattoos and compete for prizes that recognize their work. Ralph regularly went to conventions until, at one organized by Hell’s Angel’s, a woman won a prize for cosmetic tattooing of eyeliner. Ralph’s disillusionment grew when Harley- Davidson, Warner Brothers, and Walt Disney sued tattoo parlors for using copyrighted logos: “Come on, people have been getting tats of Mickey Mouse since he was invented. And now yuppie ass wants Mickey Mouse.”

Yet Steve still feels at home, despite being opposite of the stereotypically surly “old-school tattoo artist” to which Tyrone referred. He grew up in a middle-class, three-child family in North Branford. The Malers have always been involved with arts and crafts, and they approve of Steve’s career path. Steve has loved to draw since childhood, and took art as his only honors class in high school. Between high school and The Edge, he went through some rough times. He explains, “I was just a real bad kid for years—drinking and drugs… I don’t think there’s a chemical out there that I didn’t use in extreme amounts. I had my fun. But then it just becomes horrible. You don’t realize there is another way.” Steve helped overcome his addictions by going to AA meetings, at which Jeffrey joined him. He considered becoming a nurse, but is happy to have fallen into the right business. He says, “The only thing that keeps me sober is helping others.” Steve currently lives with his parents and their relationship is better than ever. Since July, he has been casually dating Alyssa, a pretty, petite 18-year-old bartender whom he met when she came in for her first tattoo, a moon on her foot.

Ralph is a kinder version of what Tyrone calls “an old-school tattoo artist.” While skulls litter the Edge to honor Halloween, at Ralph’s station they sit year-round. There they are joined by a skeleton and demonic jester, both of which dangle from Ralph’s lamp. Bio-hazard stickers stipple everything. A book titled Dogs: How to Draw Them sits near his Tupperware jars. ‘Ralph’ is a fake name, because after numerous scrapes with the law he is a bit paranoid. As we talk he looks away from me, loudly clinking needles into jars. He is a white, middle-aged, former biker with a square torso and a tremendous belly. A thick lip-barbell and triangular silver studs between his eyebrows, combined with his many and macho tattoos—King Neptune, tombstones, eagles, knives, daggers, wizards, a guy in quicksand holding up his middle finger—make him look more threatening than the rest of the artists at The Edge. But he acts gentler than he looks.

Like many middle-aged tattooed men, Ralph got his first tattoos at home when he “started messin’ around real young with India ink.” He has been giving tats all over Connecticut since 1987. Right now he is on probation (he won’t tell me why) and is working at The Edge because it is the only parlor in New Haven that gives a pay stub, which the probation officer requires. Unlike Steve and Coniah, Ralph never studied art before learning to tattoo. “I didn’t get into the business to tattoo,” he explains, “I got into the business for the money.”

And the money is good: A tattoo artist can take home up to $1500 a week. The artists split their profits with the store, but at $150/tattoo, each of which takes around an hour, the net profit accumulates. Despite Ralph’s intimidating facade, the fact that he makes a good living from tattooing reveals that in addition to being a skilled artist, he is agreeable with customers.

At The Edge, I don’t see much of the “yuppie ass” to which Ralph referred, but I do see a diverse crowd. I meet Keri, a sensitive 17 year-old waiting for her fiancée to finish getting the Biohazard symbols tattooed on his wrists. She has a black tribal decal on her lower back, as do many tattooed young women. I meet Jim, an 18 year-old getting the logo for the straight-edge lifestyle (a vertical “X X X”) tattooed on his right calf. He explains to me that he doesn’t smoke, drink, or do drugs, but he’s not as conservative as straight-edge kids who abstain from tattoos. Neither Keri nor Jim, nor any other teenager I meet, gets grief about tats from their parents. Some parents are even inspired to follow their kids’ lead.

Christina, a statuesque, glowing, 48 year-old blonde with an MBA, quit her job as a CEO of the Wadsworth Atheneum to become a massage therapist a year ago. She received her first, subtle tattoo (a butterfly) at 35, but now says, “I’m braver. I wanted to do what I wanted to do. I’m more comfortable letting people know who I am.” Coniah is tattooing the Chinese words “healing woman,” as well as a peacock, which symbolizes “goddess” in tantric philosophy on her left leg. Coniah designed the image just for her. Two real peacock feathers are draped Coniah’s station. Christina, sprawled out on a stretcher like a reclining deity, keeps looking down her leg with pleasure at the evolving tat. She murmurs, “Isn’t it beautiful?”

Though abundantly-tattooed women occasionally feel disrespected, most women receive compliments on their tats—from coworkers and friends, if they have visible tats, or from lovers and gynecologists, if they have more hidden ones. Men are more likely to have multiple, visible tattoos, and so are more likely to feel judged by the non-tattooed. Sebastian, an artist who is pretty much covered in black tats, reports, “I go to the doctor’s and they look at me like I’m halfway dead already. Old male doctors especially are like that.”

All the artists at The Edge except Steve and Ralph believe strongly that tats should be meaningful. Steve has no clear ideology on the issue—his philosophy is: Get whatever makes you happy. Ralph snorts at the idea that tats “should” have meaning. But then he tells me that each of his tattoos, while not having symbolic value, is a happy reminder of the friend who gave him that particular tattoo, even if the friendship faded long ago. If the artist doesn’t like a customer’s idea for a tat, he or she will try to tactfully talk the customer out of it. Steve once refused to do a tattoo of the yellow brick road, “because the perspective was all wrong and too difficult.” Tyrone forces his customers to think seriously about their whimsical ideas: “Don’t just get a heart or a rose because ‘it’s feminine.’ Do you like hearts? Do you like roses?” Sebastian was once asked to tattoo argyle socks onto an old man’s feet. He told the guy, “You’re an idiot.”

It is a privilege to see how a tattoo is made. Many artists believe that the art must pass only from artist to artist, not from a book. Coniah explains, “Only when [knowledge of a craft] becomes popular does an art form die.” But Steve believes that “if somebody’s interested, they should know about it.” And so he walks me through the tattooing process as we sit at his station. It is sparsely decorated. On his counter sit two framed photos, one of the singer Prince (Steve’s “higher power,” notes a friend of his), the other a still from the film of The Outsiders (when I say I knew only of the novel, Steve jokes, “You would”). Steve’s sketchbook lies open revealing anime drawings, cartoon faces that Steve calls “crazy head pictures,” and many sketches for tattoo designs.

Steve places the materials necessary for a tat on the counter. He smears Vitamin A and D ointment onto a large popsicle stick so that it will hold tiny plastic pots of glycerin ink. He shows me the two kinds of needle-tools used for every tat job—one for outlining, the other for coloring. Both resemble little guns with long needles instead of a bullet-shaft. In the first kind, five needles pack closely together; in the second, the five are spaced more widely apart. The needles are actually very thin tubes that take up ink if touched into a pot. Out of the guns’ handles twist cords that connect to a foot pedal on the floor. Steve taps the pedal, demonstrating how the needles (currently empty) would spin to release ink. Then we move to the back room, where he prepares the skin-transferable print of a conjoined sun and moon for an imminent appointment. He puts his drawing of the design between two sheets of chemically- coated paper, then runs the three sheets through a machine that makes transparencies. Out comes a purple print between the chemical-sheets. Steve will press this against the skin of the client.

She arrives: Cindy, a cute blonde in her late twenties. She is cheerful, giggly, and dressed for a Gap ad. She is here for a cover-up of a moon on her belly, a tat she got in 1994. Cover-ups, along with tats that circumscribe the upper arm, are the bane of every tattoo artist. The latter requires an extremely calm, still patient; a cover-up demands that the artist have great skill and humility. One needs skill to transform the original design, and humility to face altering another artist’s vision.

Steve has designed a half-moon to fit over Cindy’s faded crescent. He takes a “before” photo of the crescent, then attempts to line up his print over the tat. He cleans Cindy’s faded moon with rubbing alcohol, then swipes clear deodorant over the skin so the print will stick. The print lines up only after three tries. Steve makes a new print and re-cleans the skin for each attempt. After the successful fourth try, Steve takes up the outlining needle and traces the purple print. Cindy does not flinch, reporting to me that “it doesn’t really hurt, just feels a little irritating, like an ongoing bee-sting.” After outlining, Steve switches to the coloring needle. Every trickle of color is dabbed and wiped with a paper towel. Soon Cindy’s stomach looks like a finger-painting project. Steve wipes another towel over the chaos, to clean away excess ink. Color stays only where the needle has actually touched the skin. When the tat is finished, Steve disinfects the needles in a hot sterilizing solution and throws them out.

“In the old days, we used needles over and over,” Ralph once told me with nostalgia. But Tyrone is proud of the cleanliness and safety of his parlor, which forbids pets, food, and smoking. Any impurity in the air might taint the ink, which in turn infects the bloodstream. Steve takes Cindy outside to look at her tattoo in sunlight, and Sebastian comes along to approve the job. Once back indoors, Steve takes an “after” photo of that tat to add to his album of work. He then covers the sun and moon with Vitamin A and D ointment and tapes gauze over the tat with band-aids. He hands Cindy packets of the ointment to apply to the area for three to four days after. Cindy is clearly pleased with Steve’s work. She thanks him and says goodbye.

“Hello,” announces a customer to Steve one day. He is a middle-aged black man with bulging, tat-covered arms. He is at once solemn and frustrated. “I had an appointment for right now with Sebastian, and he’s not here. I need this tat. I just got back from my mother’s funeral.” He is here for the day from Florida, and Sebastian is the only tat artist he works with anywhere. But Sebastian apparently forgot the appointment. The man wants the image of praying hands (modeled after Durer’s sculpture) entwined with a rosary tattooed on his upper arm. All the artists at The Edge know how to do this popular image, but Steve is reluctant to take Sebastian’s client. The fellow is desperate: “Please, man. Make it special for me. Dude, I don’t move.” Steve considers a bit, and agrees to design the tat. He retreats to his station to sketch, while the man joins me at the counter.

I hesitantly smile. He speaks first. “I take a lot of pride in this place. Steve, for example, that’s good that he’s doing my tat. I don’t like to see this place slipping—I mean, where’s Sebastian?” I nod. I don’t feel uncomfortable, just sort of baffled by the situation—that this is where the man has come right after his mother’s funeral, that I am the person he’s talking to. I ask the man the same question I’ve been asking everyone at The Edge: Can you tell me about your tattoos? He extends his right arm near me, holding it so I can see a large cross on his biceps with names on each limb. “You see this? I got four kids—daughters—and with their names here, that’s unconditional love. Those kids are mine. It’s not like a marriage. When you put that on your arm, that’s total devotion.” Then he starts weeping, pauses, and keeps talking. His eyes dry as he talks.

His name is Chet McGill. He shows me his right arm, on which sprawls one of Sebastian’s designs, an eagle killing a snake. “See, Sebastian thinks of me as a warrior— an eagle—because that represents strength.” And there is precedent for his getting a tattoo in memory of a loved one: When Chet’s Cherokee grandmother died, Sebastian designed a tattoo of an Indian on a horse for Chet’s upper back, the Indian’s head down in mourning.

Steve finishes Chet’s design in about twenty minutes. Chet has invited me to watch him get the tat, so I perch on Steve’s counter to watch him work. His job right now seems enormously important. This would-be nurse and dedicated artist with a natural bedside manner is far from the old-school bully-tattooer. He rolls up Chet’s sleeve and begins to tattoo the praying hands.

Emily Kopley, a Senior in Branford College, is on the staff of TNJ.