Ray Joyner pulls his cab up to the New Haven Hotel at the intersection of Temple and George Streets in response to a call from a customer looking to travel a few blocks to Union Station. Because New Haven is a busy city, especially during rush hour, there’s nowhere to pull over to wait for the customer to appear. So Joyner decides to drive around the block instead.

But New Haven’s grid, filled with one-way streets, does not make circling easy. Joyner continues heading southeast on George Street, turns right on Temple and right again when the street dead-ends at North Frontage. He can’t take a right on College, so he has to go up to York. From there, he turns on George and drives three blocks before making it back to the hotel where he started.

“By the time we go around the block again, we have no customer,” Joyner explained. “On a Friday, it can take ten to fifteen minutes to go around the block.” Potential patrons, often in a hurry, hop in a car from one of New Haven’s ten other cab companies.

“Ninety percent of the people I was supposed to get, I never get,” Joyner claims. He picks up a customer, sure, but it’s usually not the one who called.

Yale Security and New Haven police don’t let cabs block traffic downtown, so customers asking to be picked up at Phelps Gate, the entrance to Yale’s Old Campus, often run into similar problems. According to Joyner, “they yell and scream and curse” when they walk out of the gate to find no cab waiting.

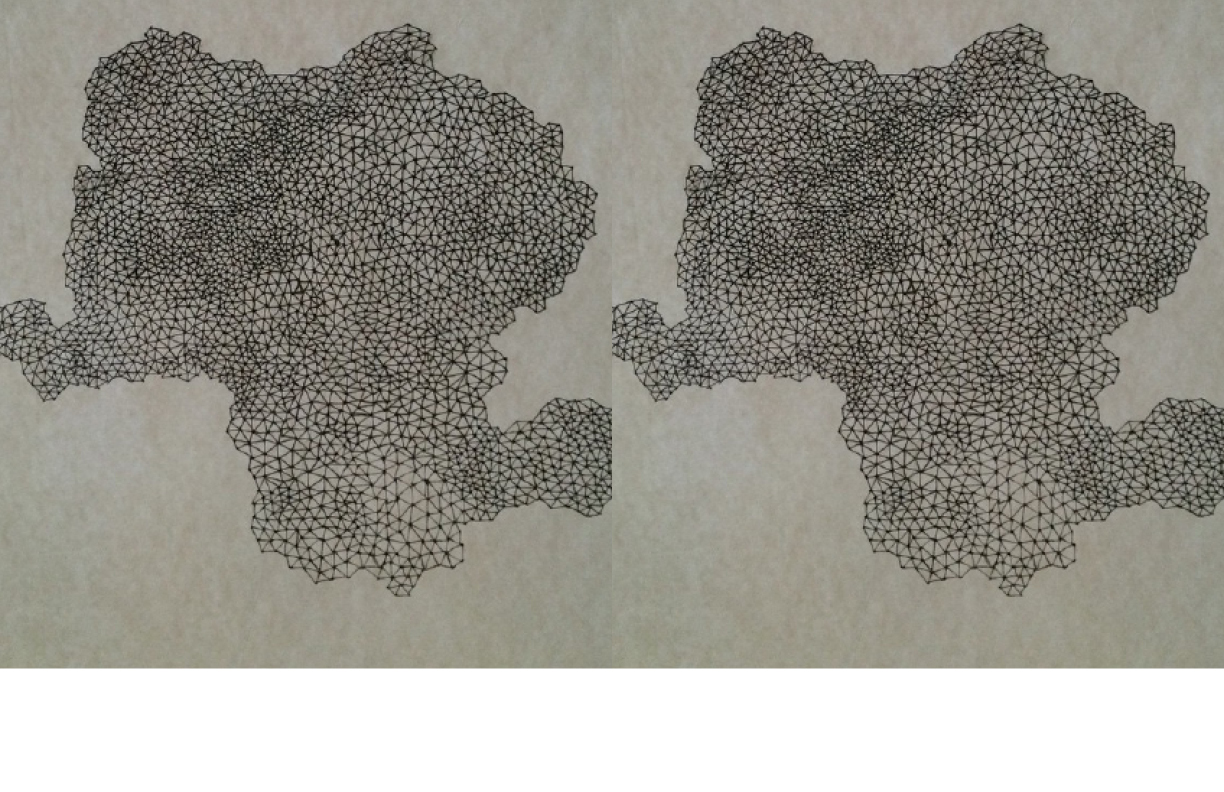

New Haven’s streets were first laid out in 1638 around a system of nine squares. This design, a perfect grid, was considered extremely innovative. Doug Rae, New Haven’s former Chief Administrative Officer and current Richard S. Ely Professor of Management at Yale, explains that the city’s plan was “very rare for that period.”

Two hundred years after the grid was first set down, the automobile made its debut, and with it came congestion. By the 1960s, in an effort to calm traffic, the city made most of the streets downtown one-way, an arrangement that has persisted to the present day. This design, Rae said, is meant to speed up car traffic. “Traffic moves in New Haven now maybe twice or even three times as fast as it did seventy years ago,” he said. City Engineer Richard Miller, for one, thinks it’s been relatively successful. “I don’t receive many complaints about the one-way streets,” he said.

But the one-way streets can annoy anyone in a car used to walking by more direct routes. To get from Phelps Gate to Broadway, for example, Joyner must drive four blocks out of his way. “Customers get upset because they think I’m taking them for a ride,” he said. “In some instances, it’s quicker to walk.”

Though he now lives in Stratford, Joyner, 49, grew up in New Haven. “When I got my license, people drove with a little more courtesy,” he said. Though the layouts of the streets haven’t changed, “traffic is ten times as much as it was when I was younger.”

Joyner’s stint as a New Haven cabbie began about a month ago. Before that, he drove in Milford and Bridgeport, where two-way streets and free parking abound.

“New Haven is pretty unfriendly to the automobile,” Rae said. “The really vital thing about New Haven is that the downtown and Yale neighborhoods center on pedestrians, and, to a lesser extent, bicycles.”

According to Miller, there are an increasing number of cyclists in the city, a fact he attributes to the resurgence of the green movement and the heavy concentration of schools in the downtown area. Yet there are few bike lanes on New Haven’s streets and biking on the sidewalk is illegal, so cyclists, like Brian Tang, TD ’12, have to ride next to cars.

Tang, a former intern with the New Haven Transportation, Traffic and Parking Department, says that, “From the perspective of a Yale student, it feels like somebody should be making an effort to make things safer for Yale’s campus and to make it easier” for bicyclists to get around safely. It’s the duty of a city to protect its citizens and facilitate transportation. Bicyclists, however, aren’t always playing by the rules either.

Though bicyclists are supposed to obey traffic signals just as cars do, many often cross the street with pedestrians instead of waiting for a green light. Moreover, in an effort to avoid the same indirect routing drivers face, cyclists often go the wrong way down one-way streets. The problem becomes particularly acute on smaller, single-direction roads not intended for through-traffic, such as Wall Street, whose direction switches every couple of blocks.

In an effort to reconcile the needs of drivers, bicyclists, and pedestrians, the city is working on compiling a Complete Streets Manual, to be finished by the end of the year. The pamphlet will assess the conditions and usage patterns of every street in New Haven. “We’re looking at trying to be much more aware of the context” to determine how to address traffic needs on each street, Miller said. He stresses that many forms of technology for traffic control have already been developed; the city only needs the money and time to implement the new ideas.

For now, people like Joyner and Tang try to adapt to the idiosyncrasies of New Haven’s streets. Perhaps in time, the city will realize the need to adapt to them instead.