Architecture tells stories.

Before books, buildings, the silent stonework of buildings conveyed elaborate narratives sans words. In churches and cathedrals, sculptures, carvings, and stained glass windows told religious parables to those who couldn’t read or gain access to books. Who needs bound pages when you could have dappled light illuminating characters rendered in marble or limestone? Victor Hugo wrote that before the invention of the printing press, men who were born to be poets became architects. After Gutenberg made the mass production of the written word possible, men who were born to be poets could just be… well, poets.

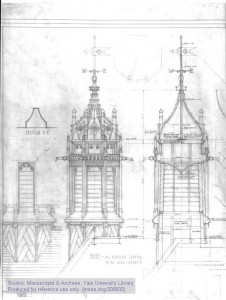

But James Gamble Rogers, the architect of Yale’s Harkness Tower, Sterling Memorial Library, the Law School, and many other campus landmarks, was something else: a poet-architect. “Every door, every nook, every cranny tells its own story,” says Yale School of Architecture Dean Robert A. M. Stern of the buildings. “Students have come to fiercely and passionately embrace his charms and storytelling and wit.”

Harkness Tower, for example, boasts four grotesque birdlike figures that represent the misshapen, malleable freshmen who come to Yale to be formed into successful graduates. Above them are four statues representing professions that Yale students generally pursued: law, business, medicine, and the ministry. Some conventions, it seems, really are set in stone.

A hallway in Sterling Memorial Library leading to the Manuscripts and Archives room contains twelve carvings of students, one between each window, memorializing the lifestyle of high scholarship. One boy drowses over his books, while another drinks an overflowing mug of beer beneath a picture of a curvaceous woman. A student listens to a radio, books neglected, while another reads, in large type, “U. R. A. JOKE.” The final stone student, however, sits on a globe, triumphantly clutching his diploma. He is the successful Yale graduate, on top of the world.

The mood of Roger’s architecture may be lighthearted, but his work was ambitious and artistically serious. “The level of detail – the scholarship and invention and wit – that went into the design of those buildings… was something that had never been seen at Yale’s campus,” said Stern. “It celebrates the entire history of the university. It’s filled with tributes or references to where Yale was located, where its founders came from, who the great professors were and so on.”

According to Judith Schiff, the chief research archivist for the Sterling Memorial Library, each stained glass window in the library corresponds to the purpose of its room. Even the faculty lunch room, now sparsely furnished with a fridge and a microwave, has beautiful stained glass windows with motifs of food from Mother Goose rhymes: Little Jack Horner, the “Queen of Hearts who made some tarts,” and Jack Sprat “who could eat no fat.” “It’s not the beautiful place it once was. It’s become more utilitarian,” said Schiff of the lunchroom, whose windows no longer get the attention they deserve.

In a library room intended for natural sciences seminars, a fire-breathing dragon keeps company with birds, fish, reptiles, and serpents. In one meant for the study of mathematics, a glass James Watt tinkers with a tea kettle in one window, while Benjamin Franklin flies his kite in a lightning storm. Huckleberry Finn is up to no good in a stained glass medallion in a room for American literature, while Moby Dick swishes his tail in another.

The Law School, too, is rich in embellishment. Take, for example, the carving at the gothic entrance at 127 Wall Street, depicting a lawyer with the head of a parrot and his client with the body of a goat. In the panels found over the doors at this entrance, two scenes with darkly humorous implications confront the already offended law student: In the scene to the left, a stone courtroom is filled with clamoring lawyers doing their best to convince a sleeping judge of their cases. To the right, an earnest professor lectures to a classroom of snoozing students. All that’s missing are cartoon Zs floating up to the ceiling.

Elsewhere, over an entrance to the Law School on High Street, a student slumbers, surrounded by books. Next to him are an owl, a friendly-looking mouse, and some cobwebs. The slacker, it appears, was an endless source of inspiration for Rogers. On a stone cornice at the east end of the north wall of the Law School courtyard, and with seemingly with little explanation, is a stone figure of a snail. Wigs and Woolstacks, a 1934 pamphlet on the facility’s architecture, helpfully explains that the gastropod—what else?— “represents the speed with which the law works.”

Snails and slackers aren’t the only noteworthy figures immortalized in stone. Ask Dean Stern where to stop on an architectural tour of the Law School, and he’ll send you to his own favorite detail: a portrait of its architect embedded in the building’s stone wall. Perhaps Stern, who is designing Yale’s two new colleges, has ambitions of his own portrait being incorporated into the university’s architectural narrative. He wouldn’t say straight out. It seems, however, visitors to colleges 13 and 14 should be on the lookout for a little stone Stern.

“Consider the hint dropped,” he said.