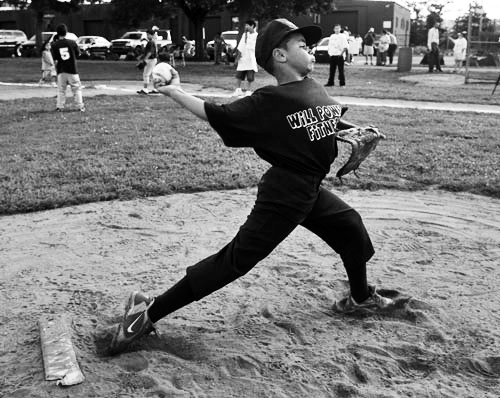

Three years later, the remnants of Jericho Scott’s brush with youth baseball superstardom reign neatly over his small bedroom. A signed shirt from television personality Jimmy Kimmel hangs on the wall next to Jericho’s own FatHead, a brand of oversized wall sticker usually emblazoned with the likenesses of major league all-stars, not scrawny nine-year-olds pitching for pizza parlor-sponsored youth teams. His limbs flailing and his face scrunched into a ball of childish effort, the Jericho whom the sticker depicts hurls one of the famed fastballs that got him kicked out of his league and into the national media spotlight. Today, Jericho cringes a bit at the image. “I don’t like how I look in that one,” he says.

…

On August 20, 2008, Jericho, now 13, took the mound at New Haven’s Criscuolo Park for the then-undefeated Will Power Fitness team of the Liga Juvenil de Baseball, a small summer league he’d joined mid-season. The L.J.B. warned that Jericho, an above-average pitcher in this new league who was still only the third-best pitcher on his spring PONY League team, threw too hard and needed to change positions or move into an older age group. Jericho’s coach and parents ignored the warning and sent him out to pitch. After league officials promptly declared the game a forfeit and Jericho broke down in tears on the mound, editorials from New Haven to Idaho argued that the young boy was punished simply for being too good.

Over the coming weeks, as the Scotts raised money for a lawsuit against the league and the league held press conferences defending its decision, media outlets around the country trained their gaze on Jericho and turned a few bad decisions into a morality tale for the ages. It started when Jericho’s mother, Nicole, brought the story to News Channel 8 in New Haven. Soon journalists descended on Jericho’s home. Jimmy Kimmel and Jay Leno came calling. Mourn the enforced mediocrity of our youth! yelled talking heads on ESPN. Look at the home mortgage crisis if you think youth baseball is the only place where people are no longer allowed to fail! wrote others. Jericho was featured in a three-minute segment on the CBS Early Show in which he’s seen pitching on a sidewalk in New York City. He fumbles his catcher’s nervous return tosses and hides behind his mother’s legs as a crowd looks on. The eager host exclaims at a 47-mile-per-hour fastball that is in fact average speed for a nine-year-old.

It was a display of rampant journalistic moralizing, though Jericho and his parents say they never felt victimized by the media. But why did Jericho become a national media figure in the first place? I was amazed when I stopped to think about what Nicole reportedly yelled that August afternoon. “This will be the last year,” she shouted. “Once the lawyer is done they’re gonna eat shit and there ain’t gonna be a league next year.” I wanted to know why it all mattered so much.

…

Nicole runs a lively, orderly home in the rundown community of Fair Haven. Outside, teenagers hang out on street corners and trash litters abandoned yards. Inside, when I visit her, Nicole gracefully juggles the needs of her three daughters, who all have come down with a bug. She passes judgment on requests for soda and Wii as we talk about her children. “This neighborhood’s not the best,” she says. “I try to keep them focused on doing things to stay positive, enrolled in stuff so they’re not in the neighborhood.” Leroy, Jericho’s dad, stops in for dinner between a full day at work as an auto mechanic and a class his union is holding.

Jericho is an A student and a self-professed “neat freak” who has become one of the best thirteen-year-old pitchers in New Haven, according to his long-time coach Mark Gambardella. Gambardella coached the better-organized spring outfit on which Jericho played before and since the pitching incident. Yet still, Jericho’s parents worry. “You don’t want me to talk about Jericho,” Leroy said abruptly when I called. “Me and him, we’re having a tough time.” As Leroy sees it, Jericho’s been dealt a good hand—two parents, a stable home, a supportive coach—and hasn’t quite had his eyes opened to the misery that is only a few bad decisions away for him. “He doesn’t know what it’s like to have nothing.”

Jericho has never been in serious trouble, but Leroy wants him not to forget that his talent and upbringing alone won’t save him in a town where “you have fourteen-year-olds holding pistols.” Jericho carries himself with self-assuredness, but both Leroy and Gambardella know a sensitive boy beneath the “city front.”

“I’m not sure how strong he is on his own,” Gambardella said.

…

Once the public outcry against the league’s injustice faded, the Scotts became easy targets for criticism. John Williams, the prominent New Haven civil rights attorney who handled the Scotts’ lawsuit, describes the case now as a “typical example when adults meddle needlessly in the lives of their children.” Craig Fehrman, a graduate student in English at Yale and the reporter who covered Jericho’s story for Deadspin, a sports news Web site, told me that Nicole and Leroy “were putting a bad energy into the kid, where the way he performed in sports was a reflection of them.”

Nicole, who admits that she and Leroy are “the loud parents” at games, can certainly be held responsible for feeding the media fire. Gambardella said that “Jericho would have stayed probably quiet if it was up to him.” Nicole still thinks that her lawsuit against the league will make it to court and vindicate her, even though Williams says he gave up years ago. “It could go on till Jericho’s 19 years old,” she proclaimed.

And the notoriety has worn on Jericho. “He doesn’t show it, but it’s really hard on him,” Leroy said. “With the exposure he’s had, it’s a little worse for him. He’s known in the community. You can’t be an average kid egging someone’s house on Halloween.”

Yet to criticize the Scotts for their stubbornness would be to ignore the central place baseball occupies in their lives. Baseball is not a peripheral passion for the Scotts, a game during which they relax their parenting principles and indulge in narcissism. In a neighborhood they mistrust, the stakes are high, and baseball is the game to which they cling for signs that Jericho is the courageous boy they need so badly to see. For better or for worse, baseball is the community, the coach, and the ethics that the Scotts are betting will guide Jericho into adulthood.

Mark Gambardella knows well what could lie ahead for his players. “I had one team that, right now, my first baseman has killed a teacher at Cross, my shortstop put an ice pick down at Fireside Café into somebody’s back, my catcher did armed robbery,” he said. (Cross is a nickname for Wilbur Cross High School in New Haven.)

Baseball doesn’t just keep Jericho out of trouble. It offers a home to the whole Scott family, from four-year-old Carizma, who is Jericho’s most loyal fan, to Jericho’s older brother Alex, who also played for Gambardella. Nicole joined the ranks of youth baseball coaches this season, signing on to lead a tee-ball team that included her young daughters. Next year, she says, two of her daughters will be playing for Gambardella, who also coaches girls. Even sitting in the stands is important to Nicole, who said she doesn’t hang out much around their home. Jericho’s team includes many families from outside Fair Haven, and early Saturday mornings at the local field and late evenings on tournament trips to Long Island have built friendships that the family holds dear. “That’s what we do,” Nicole said. “We get dressed in the summer and we’re at the baseball park. That’s where we’re at all day.”

Then there’s Gambardella, who played as a boy in the same league in which Jericho now plays and has spent the last thirty-two years coaching youth baseball, seven of them with Jericho. In terms of cost and time, Gambardella offers the Scotts and other families a bargain they won’t find elsewhere. He started a small new league this summer because parents’ other options were too expensive, and twice as many kids signed up as he expected. Gambardella and his son simply doubled their coaching duties. “We made a commitment,” he said.

“Mark is part of our family, outside of sports,” Nicole said. The man whose connection to Jericho was forged through hundreds of pitch signals now comes to every birthday party and graduation ceremony. He was there recently as the family mourned the death of Nicole’s grandmother, who had lived with Nicole her whole life.

Gambardella can identify with his players. “I was no angel growing up, either,” he said. He knows that his duties extend into foul territory and well beyond the fence. “We try to teach ’em life. I like to give ’em someone to talk to outside of their family.”

Jericho has been begging Gambardella to coach an older team next year so that he doesn’t have to move on. “He’s like a father to me,” Jericho said. “And my mom. More like a grandfather to me.”

I wanted to tell this story without any made-for-TV moralizing. But for the Scotts, Jericho’s story does have a moral—an important one. They depend on baseball to teach in an immediate, physical way lessons that aren’t communicated elsewhere in Fair Haven. In the old news stories, the Scotts’ complaints about the bad message the league was sending sounded trite. In person, their claims were urgent and alive. “I teach him, whatever you do, try to be the best at it, in school and baseball and everything else,” Nicole said. “He wasn’t doing anything wrong.”

Leroy’s voice rang with the same intensity as his wife’s. “If you practice hard enough, you can be the best you can be,” he said, after I asked him why the incident made him so angry.

Now, Jericho sometimes finds himself unable to keep up with older kids’ fastballs. “Am I gonna say ‘I don’t want him playing and your kid can’t pitch to him anymore’?” Nicole asked. “If my kid can’t hit, then he needs to practice more. He needs to go to the batting cage and turn it up a little bit and practice more. You can’t hit ’em today, but next time you will. And sure enough he does.”

…

Back in his room, Jericho mostly mumbles through our conversation about baseball. But his voice perks up for the first time when he tells me that he also likes to draw. He shows me a handsome sketch he made of Goofy—nose wrinkled, eyes protruding, face lit in bright Crayola hues—with a note for his mom on her birthday. He has more, he says—his favorite piece is a picture of a skull and crossbones with guns—but they’re all packed away. After all, months of attention taught Jericho what I’m really interested in. He takes an 8.5 x 11 glossy photo from a stack in the kitchen and offers to sign it for me. “Thank you for your support,” he writes.

Photograph: Douglas Healey / Associated Press