Eight-year-old Yaqub Bajwa is, on average, a foot shorter than his friends and ten to fourteen years younger than them. Their stature gives them a bit of an advantage over him in volleyball, but he is their equal in games of Risk. Sometimes they talk about basic chemistry and other times they talk about Madagascar 3. As a kid growing up at Yale, Yaqub regularly interacts with a world he is too young to fully participate in—or understand—but that doesn’t keep him from trying.

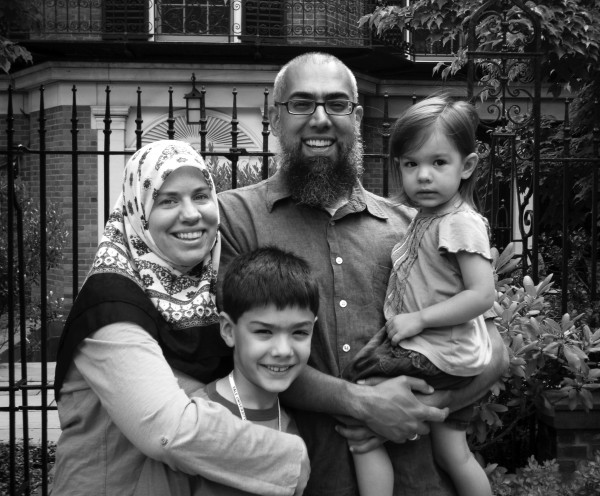

At 5:30 one evening, I see Yaqub saunter into the Timothy Dwight dining hall beside his mother Lisa Bajwa, TD resident fellow, who holds his two-year-old sister, Aya, propped on her hip. His father, Omer Bajwa, has some business to attend to tonight as Yale’s Muslim Chaplain, so it won’t be a full family dinner.

Yaqub runs into his friends as he meanders through the dining hall. When they ask him how his day is going, he launches into the saga of his extraordinary life: how his sister has recently learned how to turn doorknobs and keeps coming into his room to steal his stuffed animals, or how he hid a plastic spider in his teacher’s book as a practical joke. Yaqub knows how to work a room.

I catch a glimpse of Yaqub as he rolls his eyes at his sister Aya when he sits down at a table. She is pushing her toy stroller around the dining hall, but it won’t quite fit between the packed tables and she is starting to fuss. I sense his mom panic ever so slightly about a temper tantrum brewing. She placates Aya by promising her that she can draw with the sacred box of markers when they get back to the apartment.

Yaqub and Aya have to behave beyond their maturity levels because they spend so much time in public. Yaqub in particular has to assume two personas—one that’s playful and relaxed inside their resident fellow’s apartment and one that’s composed and well-behaved around TD. “When we moved in, we sat [Yaqub] down and told him he had to have a certain respectful tone of voice in public,” Bajwa said. “You always have to be on when you’re out.”

Bajwa believes that his son has grown up a lot even in the few months since his family moved into TD. Since Yale students lavish so much attention on him, Bajwa sees what he calls their “emotional intelligence” beginning to rub off on him. “My kids have become more socially mature and more sociable since coming here,” he said. “It’s noticeable. My parents have said it. My in-laws have said it.”

Being a Yale kid comes with perks. Clare Hungerford, eleven-year-old daughter of Morse Master Amy Hungerford, and Marty Keil ’12, son of former Morse Master Frank Keil, both told me that one of the best parts of being a campus kid is the Master’s house. When Marty moved into the Master’s house at age 11, he was most excited that it had the Game Show Network. When he went to dinner in the Morse dining hall at night, he could drink as much soda as he wanted.

Clare gets to have a lot more sleepovers than before because the house is much more spacious than her old one in East Rock. When her friends come over on Saturday nights, they watch movies and talk and play, and marvel at the floor-to-ceiling glass windows on the lower level of the house that reflect the image of the living room at night. But her peers are conscious of the oddness of her home. “They think it’s cool, but they wouldn’t want to do it,” Clare said.

Having people in your house so much of the time takes some getting used to. A self-proclaimed dog person, Clare uses her new puppy, Toller, to help her integrate into social situations with older people. Her mom has noticed. “It helps her to feel like she has a role if she’s taking care of him in this context of a busy party,” Hungerford said.

Clare learns a lot from the guests and students she meets, but knows that she occupies a strange space at Yale. She’s not a peer, not a friend, but rather a fixture of Morse life. “Yale students are nice,” she said. “I kind of talk to them. But they talk more to each other.” Ultimately, this place is a club to which she is occasionally given elite access and from which she is also occasionally barred.

That boundary between Clare and Yale students even exists for 17-year-old Kate Bradley, daughter of Branford Master Elizabeth Bradley, despite her involvement in campus activities. She plays intramural squash for Branford, uses the library and the gym, goes out to New Haven restaurants for dinner with her brother, and gets advice from Yale students about what to study and what college life is really like, but Kate still knows that there is an invisible gulf between herself and the average Yalie. “A lot of students are only one year older than me, but it feels like there is such a difference between us,” she said.

During his seven years living in the Morse Master’s house, Keil took full advantages of those boundaries. He said any student who happened to see him walking around Morse when he lived there would have thought of him as that “quiet Master’s kid.” He isolated himself from Yale student life, choosing instead to focus on the trajectory of his own life; it took him until senior year of high school to learn how to get to Old Campus from Morse.

His world felt a little more normal than many Master’s kids’ because most of his friends at Hopkins School were also connected to Yale. His good friend Joe Schottenfeld, son of Davenport Master Richard Schottenfeld, is exactly Marty’s age. Joe had his bar mitzvah party in the Davenport dining hall. Marty had his eighth grade graduation after-dance in his living room. It was an unusual way to grow up, but they normalized the experience for each other.

At fourteen years old, Marty told the Yale Daily News that he was “definitely tired of Yale,” but now admits in retrospect that he did not even really know Yale until Bulldog Days, when he thought about it as a college option for the first time.

Clare is adamant about not wanting to go to Yale for college. “If I stay in one place and experience everything I have all over again, it’s not really a completely new experience or getting away from mom and dad,” she reasoned. Clare already overhears students stressing about midterms and congratulating each other on consulting jobs. She sees fliers for information sessions about studying in China and running HIV clinics in Ecuador. And she hears her mom get out of bed at 2 a.m. to break up parties, knowing that students are outside behaving in ways that she has been taught not to behave.

Amy Hungerford is not too worried about Clare observing those moments. “I am sort of fearless about knowledge in children,” Hungerford said. “There’s an occasion to talk about what they’re learning and seeing in the world.” These conversations happen very openly in Kate’s family as well. “When we talk about it, my parents treat me like an adult,” she said.

Since Bajwa is raising his children in the Muslim faith, which prohibits drinking, college partying will eventually call for serious conversations as Yaqub and Aya get older. But those discussions are still a long ways off. “I think if my kids were teenagers and they were seeing kids partying on Friday nights, that would have been more worrisome for me,” Bajwa said.

The kids of Yale see hundreds of examples of ways to be in the world while growing up here. These kids are imagining how they will navigate their college experiences and, like the students, learning how to mold the people they will become.

As Yaqub and I walked out of the dining hall after dinner, he pointed to the lit windows around the TD courtyard to show me where all of his friends live. He’s seen some of their rooms multiple times. He was sad that I had to leave, but he wanted to know what residential college I was in. Although he hadn’t heard of Morse before, when I mentioned that it was right next to Stiles, his eyes lit up. “My family eats in Stiles all the time. Maybe I’ll see you there at dinner again.” Just like any Yalie, Yaqub has learned how to organize his social life around meals. I’m sure I’ll see him there soon, stealthily carrying a plate of French fries to his seat before his parents can stop him, and beaming with pride every time a friend puts out a hand to give him a low-five.