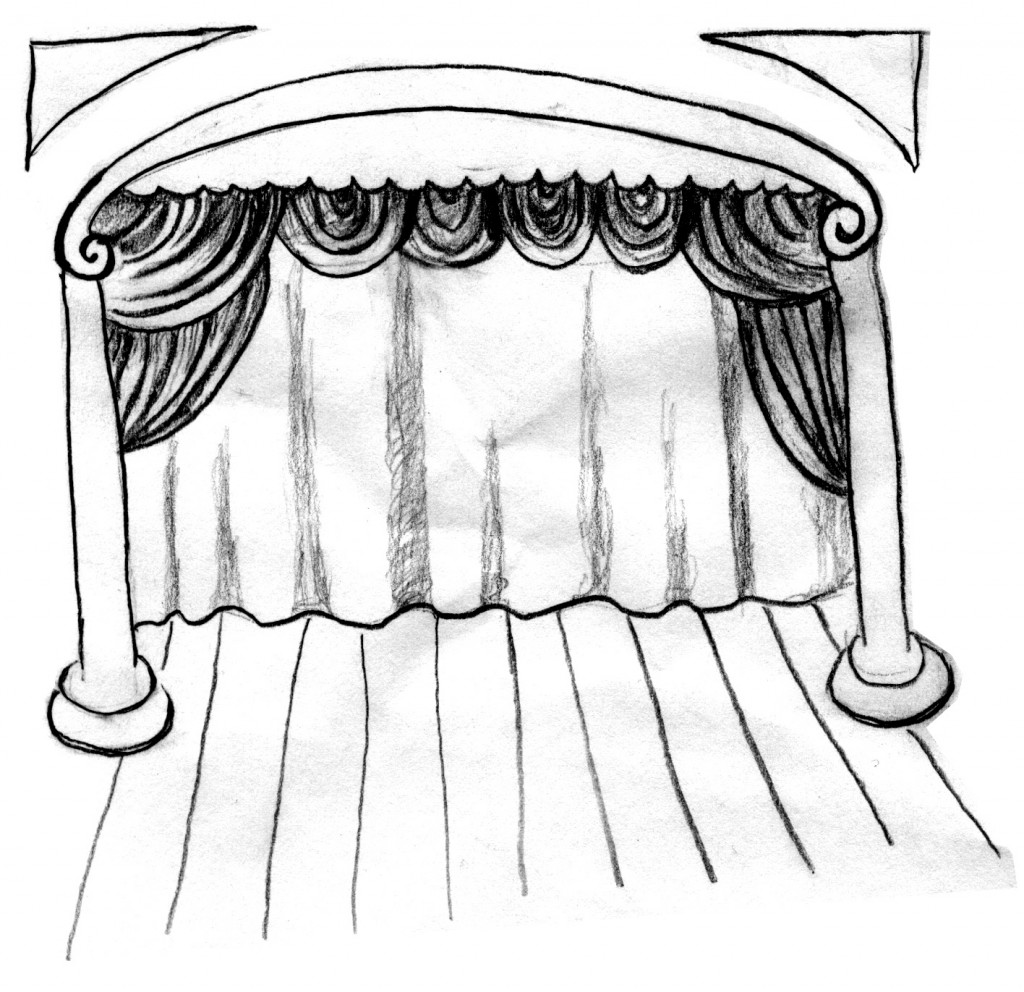

One minute at Lyric Hall and I was on stage, under the 1913 proscenium arch. Dim yellow chandelier lights gave the brawny columns a static glow.

One minute at Lyric Hall and I was on stage, under the 1913 proscenium arch. Dim yellow chandelier lights gave the brawny columns a static glow.

I hadn’t played a piano with ivory keys since the old tattered one at my neighborhood music school. Rough on the skin, this piano recalled the other’s grandmotherly world-weariness. Plastic keys aren’t for John Cavaliere, the owner of the building and the proprietor of Lyric Hall Antiques and Conservation—they’ll never have the charm, the honesty of ivory. He’s built his business, his home, and his life on preserving that honesty, on reviving the old and celebrating the forgotten.

Founded in 1913 as a vaudeville house by Italian factory workers, Lyric Hall now plays three roles: that of Cavaliere’s antiques and conservation business, that of a performance space, and that of his home. Cavaliere, who studied art at Connecticut College, is a master craftsman. He specializes in gilding, but also works with wood, metal and upholstery. He purchased Lyric Hall in 2006, and since 2010 it has hosted various theater productions, musical performances, and poetry readings.

When I walked in at 2 p.m. on a Sunday, Cavaliere, who has a slim goatee and curly hair that creeps onto a wide forehead like ivy, greeted me and brought me straight into the theater at the back of the building. A teal 1930s cigarette machine offering Kents and Marlboros for 30 cents a pack stood conspicuously in the cold foyer.

The first objects to catch my eye were five golden, shell-like footlights that sat poised in a row upstage. Traditionally, ornaments of this sort were used to shield stage-illuminating candles from the wind. At Lyric Hall, armed with electric bulbs, they are less practical. Cavaliere laid new gold leaf on the old shells himself.

When Cavaliere bought the building almost a century after its construction, it was in ruins. “Nobody knew it was a theater for eighty years,” he says. All that remained from its vaudeville days was the proscenium arch. Light projected into the theater space through cracks in the walls and gaping holes in the ceiling. Cavaliere tore away strata upon strata of flooring and carpeting, each layer corresponding variously to the building’s days, post-vaudeville, as a bicycle shop, a flower shop, a joke shop. He and a revolving cast of friends, craftsmen, and hired help tore away the filth, repainted the walls, replaced the ceiling, and redesigned the façade. They began installing structures they found in antique shops or unused theaters and hotels. The building is a part of the antiques collection that it houses; you can almost feel the haphazard, stitched-together quality of the walls.

Cavaliere developed his love for old objects as a kid visiting his grandparents on Eld Street in East Rock. They had bought their house, fully furnished, in the thirties. Cavaliere liked to play with the antique furniture and other paraphernalia stored in the loft of their back carriage house.

After focusing on portraiture in college, Cavaliere turned to antique restoration. “I learn from things that have been around, things that are well made, that tell a story,” he explained. After he found Lyric Hall—“it found me,” he insists—he moved his business to Westville and made restoring the building his raison d’être.

Cavaliere and his assistants do restoration work in the studio, which is filled with scattered tools, containers with viscous adhesive liquids, and brushes of all sizes. In a corner sits an old parlor stove, a gray boom box, and a fragment of an old car wheel. A piece is missing from an enormous King George frame; he’s in the process of reconstructing it.

He took me upstairs to a balcony that hangs over the back of the theater, which is adorned by a balustrade he’s had, in pieces, for years; he salvaged it from the deteriorating Hyperion Theater on Chapel Street. I didn’t need to see that Cavaliere sleeps there to understand: He is Lyric Hall.

We sat down in the kitchen. He painted me a picture: a night at Lyric Hall. After the show finishes, everyone mingles in the reception room next to the theater, drinking white wine among ancient ships that hang in ornate frames. Cavaliere, in a thrift store tuxedo, is running around greeting and introducing, laughing and joking. “When you get all these interesting people cheek by jowl,” Cavaliere told me, “there’s this wonderful spirit. This place has this universal appeal that’s so sacred.” At night, in the shadow of the dusted and revived, Lyric Hall sustains a community. It’s a different kind of preservation.

But the hall was empty on a Sunday afternoon. Cavaliere woke up behind the Hyperion balustrade, theater empty and the floors creaky, to show me around. In the kitchen, a 1924 Glenwood stove was heating up a teakettle; Cavaliere took milk from the ancient GE fridge. A modern electric heater, probably from Home Depot, sat on the floor by the kitchen table; we laughed at how out of place it looked.

As he began to eat his cereal, Cavaliere reflected on his new role as theater producer. His friends call him the “accidental impresario.” He broke off for a moment, looked at a wall. “Actors like working here,” he said. They tell him the place has good ghosts.

Illustration by Katharine Konietzko