Four years after I hold Bill Fischer’s hand for the first time, he learns my name. “Dana? Diane?” He asks.

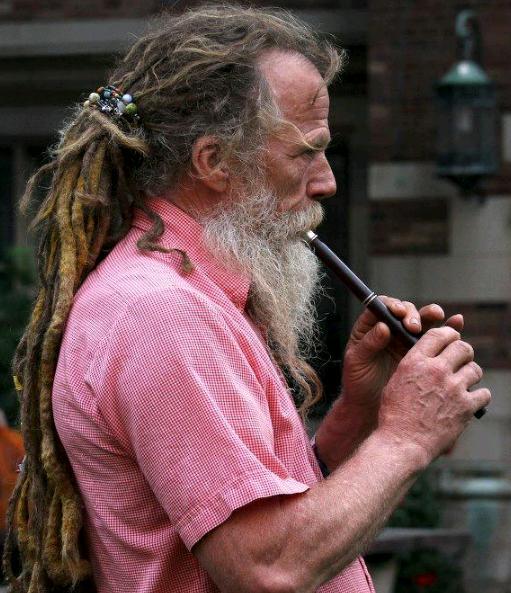

Bill’s hand grips a microphone. He is calling a contra dance—a style of group folk dance—in the barn attached to his house. It is one of his monthly parties, which require no invitation, called “Bethany Music and Dance”—BMAD for short. His fuzzy blond dreadlocks, dotted and decorated with beads and string, are bunched together on his back. His face is wrinkled and leathery, the look of someone who spends more time outside than in. His shirt reads, “May Day 2002, War on Terrorism, War is Terrorism.” His feet are bare.

We stand in the middle of the barn, below the arched beams of the high ceiling. Braided ribbons and fabrics hang on the walls and above the heads of the eighty-odd people now crowding inside, ready to dance. Wooden sculptures of bodies dangle from wires attached to the ceiling. In one corner, there is also a paper skeleton from Bill’s former doctor days. The walls are covered in posters: an old American flag with the slogan, “Give it Your Best!”; fields of wildflowers; patchwork designs on leather; an old sepia portrait; yellowed and fraying newspaper clippings. The band is warming up in the corner near the fireplace; tonight it includes a recorder, a fiddle, a mandolin, and a banjo. The air is thick and hot. It smells of woodchips and dust, mixed with the dewy, late spring breeze that occasionally makes its way inside from the open door in the back. We haven’t started dancing, but Bill’s face already shines with sweat.

He squints at me, then smiles. “I recognize you now,” he says.

**

In 1980, a slightly younger Bill Fischer had just moved back to New Haven—he graduated from Yale in 1966—when he and his wife first tried contra dancing. They were drawn to the live music and the community of strangers dancing and following instructions to the beat. Back then, New Haven had a vibrant contra dance scene, with dances three times a month, and a regular get-together for those who wanted to learn how to play the barn dance music.

A decade later, Bill bought his house in Bethany—a small town made up of mostly farmland a twenty-minute drive from downtown New Haven. Soon, people started to gather at the house, mostly to play music: Bill plays the pennywhistle and recorder and his wife plays the fiddle. The first music party happened in September 1991, with just ten or so people, but each gathering brought in more guests. The crowd increased most dramatically when another woman who held music gatherings left town in the late nineties; her frequenters heard about Bill and began meeting up at his house in Bethany. In the early 2000s, an influx that Bill calls the “undergraduate brushfire” started. Now, amateur and professional musicians alike jam in the many cluttered rooms of his house one Friday a month, along with students and former medical patients of Bill’s. Some are BMAD regulars, others heard about the dance on CouchSurfing.org. Bill himself does not seem bothered by the crowd.

“The whole thing’s evolved, but there’s no way to stop it,” he says. “It’s word of mouth, and people will find out about it. No one has squatting rights.”

He talks about his house as if he doesn’t own it all; on dance nights, it belongs equally to whoever passes in and out. He is loyal to the space, but he is more invested in the connections people make through his gatherings.

**

The night Bill learns my name, I wander in from the highway, which is lined with cars on both sides, to find his backyard buzzing with people.

I walk inside. There are dried roses and scooped-out gourds scattered along open surfaces, and various fur pelts hang in the sitting room that the door opens into. Toward the kitchen, brownies, grapes, zucchini bread, chips, macaroni and cheese, and more cover a table above a brightly patterned cloth. In a small room adjacent to the kitchen, four people are playing Simon & Garfunkel songs. On the wall a sign reads, “No smoking, no loitering, no hair combing.” In the living room, someone is playing a piano by the fireplace. Everywhere, people are talking, laughing, filling up empty yogurt containers with water, trying to fit through the crowd to get to the stairs, looking at posted newspaper clippings, asking each other’s names, if they’ve ever been here, if they’re from New Haven.

Around ten, word spreads that the dancing will start soon. Some wander up the narrow staircase and through the hallway toward the barn. As people fill the room, Bill begins practicing scales into the microphone near the band.

“Real estate is an important consideration. Is anyone too cold?” Bill says.

People smirk. It is the end of May, and every person’s face shines with sweat.

“Let’s be careful now, okay? Not just with the band but with each other,” he continues. We are bunched together in the barn so close to one another you can hardly stand without your back brushing up against someone else.

The person I’m paired with, John, stares in disbelief at the bare feet of the man to my left.

“Kind of risky, don’t you think, room this crowded, to have bare feet like that?” he asks.

The man with the bare feet is dancing with a middle-aged woman in a strappy floral dress that reaches her calves. Her brown hair sticks to her neck, and the combination of her giddy smile, hazy blue eyes, and sweat-soaked skin makes her look slightly delirious. Bill calls for us to step toward new partners. The woman looks at me with her head tilted, and says hello, extending the last syllable as she steps back. When we step toward each other again, she says, “You’re beautiful.” Then we grab each other’s forearms for a left-hand star. Sometimes the moves switch quickly, but anyone can join in and follow along. The one rule of contra dancing, Bill says, is that if you’re smiling, you’re doing it right.

At the end of the dance, Bill says that it’s time to find a new partner.

“If you have a boy and a girl, the boy is on the left. If you have a same-gender couple, bravo.”

The music starts again, but Bill yells to stop: someone in the middle is alone. Bodies shift until everyone is paired. My new partner is lanky, and a few years older than me. He has a red beard and his hair is pulled back into a bun. It’s his first time here, and he tells me he heard about contra dance through word of mouth.

“This is better than a chat room!” he says, as we do-si-do.

He has dark wings on the back of his shirt from sweat. This dance opens up into two circles, with mostly men on the inside and mostly women on the outside. Partners hit right hands like high fives, then hit left hands, then hit both hands, then both hit their hands against their own thighs each three times, then the partners swing. The women on the outside rotate around the circle, so that we swing and dance with half of the dancers. You learn a lot about a person by the way they swing—whether they jolt you back and forth, hold you with a solid hand on your back, wait for you to determine the pace, spin tightly around one foot, jump into the middle of the circle and skip. There are the uncertain ones who are scared to hold you close and the ones who make you fly.

I dance with a man named Jonah, who asks at the end, “where have these people been all of my life?”

We finish the loop and arrange ourselves for a new dance, a new partner. Before we begin, Bill tells us to look down.

“That’s your home,” he says. “Remember it, because you’ll have to find your home this time.”

**

That music and dance bring people together is no surprise, but it can be hard work sometimes, this business of getting strangers to hold hands, to see each other. There are different strategies. I’ve seen some try improvised dance or movement, which focuses on freeing the body and mind from habitual motion, entering a space to discover new possibilities of movement and interaction. Others use games or spaces of play to ease the interaction between strangers: a group in Pittsburgh called Obscure Games calls this “social grease.”

It’s a rare space where I’ve forgotten to be stingy with my love, to save my social self for designated social time. I live so much of my life in New Haven separated from strangers; here, walls between selves break down. Every person in the room is a potential conversation or connection. As we accept the night’s many gifts, like homemade lemonade in an old yogurt container, we forget that we don’t know each other. Instead, we hold hands, skip and swirl, swing and dance, find our home.

**

The first time I meet Bill in daylight is the day after he learns my name. I am surprised by the quiet in the house. I hear the screen door slam behind me.

“Bill?” I call. The pelt of a wolf I’ve never noticed hangs in front of me. I can see its nose, where its eyes would have been.

Bill wanders into the kitchen with no shirt and no shoes, wearing a pair of soccer shorts. He gives me a hug, and I say how strange it is to be here during the day, how quiet it is.

“That’s a common reaction,” he says, as he pours coffee into his drip machine.

We lean against the counter and talk about his years at Yale, some trouble he got into for drinking, his stint traveling around Alaska, his life in medical school, then as a doctor. With coffee in ceramic mugs, we wander out into his sun-streaked yard. A pen falls out of the bun on my neck. He picks it up and laughs.

“Lord knows what could fall out of my hair.”

We sit on a bench hanging from a tree in the shade, looking out into the swaying grasses of his yard where the maypole stands. I try to understand why people treat each other so kindly at Bill’s when strangers so often ignore each other. Bill’s theory is that “usual social niceties are subsumed in music and motion.”

He continues, “Social dancing, it’s not like disco, where you’re dancing by yourself or with a more dedicated partner. This is choreographed, and there’s some bozo with a microphone telling you what to do.”

He says that the warmth of the community is amplified by the fact that you have to dance with many partners throughout the evening. He laughs when he finds out that I went to my first dance as a freshman.

“I’ve known you four years, and don’t know who you are,” he says.

**

By midnight we are holding hands. Bill breaks the circle, pulling us into a spiral which unspools and leads downstairs, where we weave through cluttered rooms full of people and music, then to the basement, wandering past the ping-pong table and the punching bag, then back up to the barn. The song stops, we clap for the band, and finally, it is time for the last dance: the group waltz. The recorder slows; the notes stretch. It is the waltz where, a year ago, I began a romance that led to months of letters and poems. It is the waltz where I have been clutched by a nervous man who asked to dance without making eye contact, and then once we were dancing, counted, “1, 2, 3; 1, 2, 3” under his breath, his concentration too fierce for interruption. It is the waltz where I have laughed holding a roommate, spinning each other around, dancing only on our toes. But tonight, I sway, instead. I join into a circle with Bill, and he counts, “1, 2, 3; 1, 2, 3” into his microphone. Our sweaty arms touch and wrap around each other, and we move our feet to the beat, counting “1, 2, 3; 1, 2, 3; 1, 2, 3.”

Diana Saverin is a senior in Berkeley College.