From the Harlem-125th Street Station, it was a simple subway ride uptown to Bronxworks, a community center on the borough’s artery, the Grand Concourse. I settled into a folding chair in a bright room, facing a makeshift stage. A dozen middle-schoolers outfitted in matching T-shirts mingled onstage, nervous and excited. A tall bald guy, intense and energetic, introduced himself as a “joker,” or facilitator, and explained to the audience that we were “spect-actors,” not spectators. Then he urged us to be alert: “What’s the thing that makes you angry?”

The students launched into a short play based on their own experiences, about starting a girls’ basketball team at their school. After they seek guidance from a teacher—played by a peer of theirs decked out in a comically oversized blazer—he tells them that they need to fundraise for uniforms and equipment. The students are passed from one teacher to another, none of whom is willing to commit to coaching them. Eventually even their principal dismisses their idea.

“Who thinks they could change this?” the joker asked. Almost everyone around me thought they could. An “awww, hell yeah,” rose from the audience. We were asked to think of a possible solution, then share it with the person next to us. “Anything that’s possible in the world is possible on this stage,” the joker reminded us.

I turned to the girl next to me, who was just a few years younger than the kids on stage. But before I could launch into an explanation of Title IX, she pointed and told me, with obvious pride, “That’s my brother.”

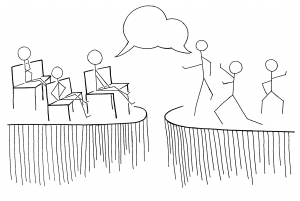

Here, the idea is that the spect-actors belong to the community, and the community belongs to the spect-actors. They know each other’s experiences and frustrations. By naming them, together, they can begin to change them. Interrogation leads to investigation, and then to transformation.

The afternoon’s performance was a format called “forum theatre,” one of many structured activities used by the Theatre of the Oppressed, a method developed in the seventies by Brazilian actor and artist Augusto Boal. Boal’s project of liberation was as simple as it was visionary, creating games that take on complex issues like internalized oppression and democratic representation. “All theatre is necessarily political, because all the activities of man are political and theatre is one of them,” his manifesto begins. Boal published the book while in exile from Brazil, having been arrested, tortured, and forced to leave by a military dictatorship. Working throughout South America with ordinary peasants and workers, he established the Center for the Theatre of the Oppressed in Rio de Janeiro. The method spread through South America, but did not stop there, making its way to Europe, New York, New Haven, and beyond.

Theatre of the Oppressed owes its New York existence to Katy Rubin, a native of New Haven. She grew up in a family of arts and activism, and first met Boal when she was fifteen. After graduating from the acting conservatory at Boston University, she started to study his method more intensively. While working as a teaching artist in New York’s public schools, Rubin noted that interactive art could improve students’ grades and behavior. Theatre of the Oppressed, she found, could be used to “activate social change” and “engage diverse communities”—but it had yet to come to New York City. Now, there are troupes with homeless actors, and strangers approach them in subway tunnels to ask, “Weren’t you in that play the other day?” Rubin says that power shifts when the ostracized are given a voice, and can become recognized.

In 2011, Rubin returned to her hometown to hold New Haven’s first Theatre of the Oppressed training. One of the jokers trained there is a woman named Janet Brodie, who in her day job coordinates group therapy at a mental health clinic on Chapel Street. Brodie, who specializes in creative arts therapy, finds that the techniques of Theatre of the Oppressed “dovetail with the goals of therapy,” helping clients to develop spontaneity and relationship skills.

Brodie’s work extends to the wider New Haven community. Most recently, she has worked on a “Healthy Aging” project, a forum theatre group for older people living with mental illness. A group of seven worked for eight weeks, creating skits and spoken word poems, which they performed along with forum theatre at local mental health facilities and for the local chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness. “Who oppresses?” her notes for the project read. “Self,” “police,” “therapist,” participants wrote. One added, “I can only go so far with the way I am being made invisible.” As the project challenges, it aims to empower. A flier for workshop participants reassures them, “If you are feeling confused in the workshops, it means that the work is going well.”

New Haven is taking the work even more into its own hands: jokers will be running their own training this upcoming September during a weekend’s crash course in Theatre of the Oppressed that ends with a performance. The project’s organizers hope the momentum continues. “It could go a million places,” Brodie said.

The New York project’s reach gives an idea of just what those million places might be. The city’s branch also conducts workshops in a Staten Island youth court; at the Harvey Milk High School, an alternative school for queer youth who have been harassed at other schools; at Housing Works, a center for people experiencing poverty and homelessness; in psychiatric hospitals and soup kitchens and public schools, with refugees, domestic workers, and undocumented immigrants.

“This is a real story. This is real life,” the joker at Bronxworks said at the top of the show. It is real life, but it is also a vision of a world of reality and possibility, of imagination and empowerment and fearlessness, of spect-actors and jokers, and crowded rooms in community centers on sunny spring afternoons.