The trees on the New Haven Green are somehow unexpected. Many of their old trunks are too wide to measure with outstretched arms, and yet I might not have paid attention to them in all the open space. It was the maps of New Haven that have taught me to truly look at them. One map, from 1748, marks out two trees on the Green and labels each of them—“2 Trees Planted in 1686”—the way a church or town hall might be identified. I cannot find them, and I doubt that they still stand centuries later.

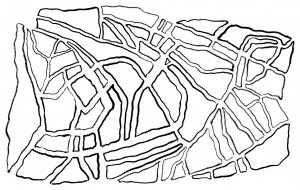

The earliest map of New Haven, drawn in 1641 by John Brockett, depicts the city as a swath of white space bounded by today’s George, York, Grove, and State streets. The area is divided into nine squares, each square subdivided by labeled divisions of land: a thin black line divides Richard Perry’s two and a half acres from Theophilus Eaton’s; Stephen Goodyear’s plot borders that of William Hawkins. The order provided by the map indicates neither cardinal directions nor street names, only the nine large rectangles and the smaller ones within them— broad outlines of a mostly uncharted place.

Over the course of three and a half centuries, those nine squares have become increasingly detailed, in construction and in representation. In a map from the eighteenth century, the allotments of land of the Brockett map become color-coded and labeled sketches of buildings. On several nineteenth-century maps, the relative sizes of blocks approach an accurate measure. A 1929 aerial photograph captures as much detail as technology could provide at the time: streets and buildings, cars and awnings, and the thin and shadowy branches of trees.

Maps create distance from places—they provide perspectives that inherently zoom out from the reality of experiences like walking down the street. Yet they echo experience, and can often augment it. For me, this has been true as long as I can remember. I grew up surrounded by maps that told me where I was in the world, and where I could go. I spent afternoons poring over the already-dated eighties atlas my father passed down to me, tracing routes and town names with my fingers; I ate many bowls of macaroni-and-cheese on a placemat with a U.S. map; I helped navigate family road trips to national parks with highway maps that, unfolded, were bigger than me.

My first experiences in cities far from home always begin with a lack of meaning, swaths of blank space. I only know that the streets are unfamiliar, sometimes winding, and infinitely detailed. At most, I know several broad strokes—a river, a central square, the direction the sun sets against a bell tower. But after an hour of walking, I can learn the perimeter of any neighborhood, some outlined terra incognita. Once I learn peripheral streets, I can let myself get lost on side streets and in courtyards, knowing that if I wander long enough, I will happen upon a familiar street I’ve already learned. Broad strokes, then specifics, a fractal-like system of zooming in, and zooming in.

For a long time, I have imagined that I no longer need a map to experience New Haven— I have convinced myself that a map of the city exists in my mind. I can visualize buildings with their various shapes, streets with their diagonal sidewalks between them. I have long stopped looking for the ornate designs of rooftops against blue skies, and dismiss the difference between rust and russet bricks on Old Campus. The city feels dense with its own private meanings, with a history I cannot access.

And yet the New Haven maps I’ve looked at reveal unseen details and rich patterns layered one over the other. On the Green, I remember only the rough sketch of the 1748 map—and the space I experience is beyond what paper and ink can record. The wind is cold. There are no people on the benches. But because of that map, I know to look for old and knotted trees.