“I was born there,” said Damien Mabry, jabbing a finger at a plain cinderblock house. “And now I live there.” This time, he pointed at another residence nearby, nearly identical to the first.

Mabry and I were standing in the neighborhood of Westville Manor, a public housing complex in the northwest corner of New Haven. It is only a fifteen-minute drive from downtown, but it feels much farther away. It is surrounded on three sides by the dense foliage of West Roc

k State Park, and its main drag, Wayfarer Street, is a two-lane road that ends in a cul-de-sac. The smaller streets that branch off it are also dead ends. As we stood outside, old newspapers fluttered over the pavement.

Elm City Communities, formerly known as the Housing Authority of New Haven, is focusing on low-density, suburb-like landscapes like Westville Manor as an alternative to towering urban projects. The approach has proved immensely popular. Though competition for public housing spots is always high, a New Haven Independent article from 2011 recounts how difficult it was to snag a coveted spot in Fair Haven’s Quinnipiac Terrace. Out of the 4,000 who entered the lottery, only 900 struck it lucky and were assigned an apartment. In response, the Housing Authority commissioned a $200 million reconstruction of another low-density complex near West Rock: Westville Manor.

Elm City Communities, which operates Westville Manor, calls it a “family development in a countryside setting,” according to its website. Yet a look at the architecture tells a different story. Westville Manor is a labyrinth of right angles and cinderblocks. Though they are designed to look like traditional homes, the units are rowhouses, with each separated from its neighbors by only a thin interior drywall. The houses, which have between two and five bedrooms, are rarely larger than 900 square feet. In an article in the New Haven Register, Connecticut architect Duo Dickinson noted that these new complexes are “blank and soulless,” and deprived residents of “pride of ownership.”

But Mabry talks about other, more pressing issues. A number of times, he has had to report water and electricity failures in his house to Elm City Communities. With ongoing structural problems—and a recent spike in violence—at Westville Manor, the “soullessness” of the houses might be the least of inhabitants’ concerns. When I visited in September, broken windows were boarded up with cardboard. Water heaters were rusted. Some houses had such little floor space that the occupants chose to convert the utility room into a bedroom. I saw an astonishing array of makeshift remedies to cover up damage, from windows bandaged with duct tape to twine suspending basement drainpipes.

Other tenants have encountered worse. In September 2013, the plaster ceiling in resident Debbie Hill’s house collapsed. One month later, Jeanette Melton, another resident, contacted New Haven Legal Assistance when she noticed water seeping through the cracks in her ceiling, the New Haven Independent reported. The attorneys discovered black mold, crumbling walls, and corroded floorboards in Melton’s household, but couldn’t go further: They lacked adequate resources and evidence. Amy Marx, an attorney with legal assistance, explained that the tenants’ rental paperwork was incomplete, meaning that the case would be hard to defend in court. Nearly a year later, no legal action has been taken.

Residents of Westville Manor often end up tangled up in bureaucracy. In the 1950s, the city of New Haven owned, operated, and repaired all of its own low-income property. Later, grossly underfunded, the city council began to distribute housing funds to private landlords through the Section 8 program rather than investigating new budget-balancing methods. This new jointly operated system has created a communication gap, not only between the public and private sectors, but between the management and the inhabitants. One tenant gestured at a huge stack of paperwork on her kitchen table, telling me how little of it she understood.

And tenants feel that the management’s accountability has only worsened. Another Wayfarer Street resident, who asked to remain anonymous, described a severe cockroach infiltration on the ground floor of her house. “I’m not going to report it, because it’s never going to get fixed anyways,” she remarked. “The unit sends someone to come look; then I never hear back no matter how often I call.”

I called Elm City Communities myself, and a representative told me that some of residents’ problems were fixed. Debbie Hill confirmed that her ceiling has indeed been repaired. But when I asked further questions about the state of the complex, I was told to contact another representative. When, after many tries, I got in touch with him, he told that I should stop calling him and directed me back to the first. The Housing Authority’s limited staff seemed too overworked to comment further.

Meanwhile, a more dangerous problem has remained unaddressed in the streets of Westville Manor: crime and gun violence. One tenant told a story of two residents robbing their next-door neighbors. Mabry, whose 7-year-old cousin was shot within the complex in August, believes that residents from nearby Dixwell and Newhallville have often been the perpetrators of these crimes. Another tenant remarked that outsiders come to the neighborhood in swarms, bringing violence and chaos. In late May, four shootings were reported within a seven-day period, and New Haven police sirens wailed ceaselessly in Westville Manor.

Violence can be a chronic problem in New Haven’s low-income neighborhoods, one that even outside organizations’ best efforts can’t solve. In 2000, Joanne Sciulli FES ’96, founded an organization called Solar Youth to offer children between nine and thirteen programs that focus on cooperation, tolerance, community service, and leadership. They began neighborhood-based programs in Westville Manor in 2008, with weekly activities ranging from bike rides to reviving the ecosystems of nearby ponds. But the staff saw the realities of Westville Manor crime firsthand when the Solar Youth house was burglarized several times in 2009.

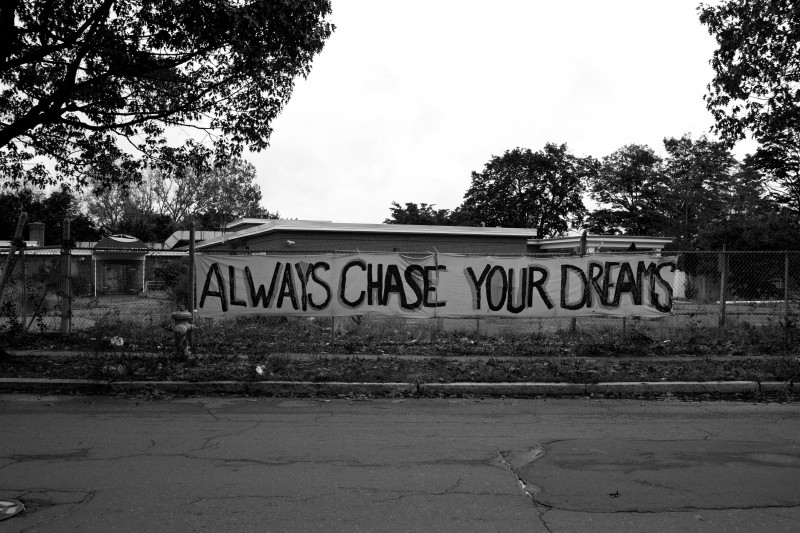

After this summer’s violence, Sciulli began to post banners around the neighborhood. One reads, “YOU ARE IMPORTANT TO US.” Another reads, “GUNS KILL, SO KEEP OFF.”

One tenant further down Wayfarer Street said that Elm City Communities is unresponsive and unhelpful on issues of both crime and internal damage. “They send out a van daily to patrol the streets and help out, but a single employee can’t really do much,” said the resident.

The tenants feel as though they have been pushed aside. A few told me they plan to leave the unit within the year, planning to move to more urban areas of the city, but most do not have the means to move elsewhere. For Mabry, though, it is a question of allegiance to the neighborhood where he has lived for twenty-eight years. “There’s a community here that nobody else ever gonna see but we who live in it because nobody bother to fix it,” he said.

But for the sake of home, he will stay and wait for repairs to come. “I’m good with it here,” he said. “We’re a tight community. We take no bullshit from no one.”

Nate Steinberg is a sophomore in Timothy Dwight College.