The Yale Center for British Art is a shell of its former self. The once-open portico at the entrance has been sealed off and replaced by a single small door. The lobby is a construction zone draped in blue tarp. The museum, closed for renovations this past January, will not reopen until spring 2016. As I walk to the front desk, I feel I’m interrupting a work in progress.

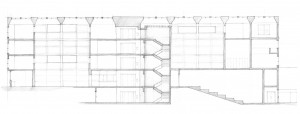

Stripped down to its steel frame, the YCBA is ready for renewal. The conservation project is the Center’s largest refurbishment since 1998. It is a critical upgrade of the nearly 40-year-old infrastructure, but the plan goes beyond routine maintenance. The Center’s staff aspires to return to architect Louis I. Kahn’s original vision, using blueprints, sketches, and notes from the 1974 construction.

“You’ll have to wear a hardhat,” YCBA Deputy Director Constance Clement tells me, “and sign this release form.” The chaotic construction site is the culmination of more than a decade of planning by YCBA Director Amy Meyers and Clement. We climb the stairs to the fourth floor, holding railings wrapped in plastic. The Center’s installation team carefully moves the art to other floors before the construction proceeds, attentive to Paul Mellon’s request that works of art he donated be housed in the building. Much of the building has been torn out—the carpets, the linen walls, the insulation, the movable gallery walls, down to the tubes that drain condensation from the windows. The gruff world of construction has temporarily taken the place of delicate paintings.

Daphne Kalomiris, an architect with Knight Architecture LLC, explains the logistics as we walk through the Center. The exterior walls will be stuffed with a mineral wool for insulation. The moveable interior walls will be raised slightly off the floor, in keeping with a 1974 Kahn sketch.

The level of attention to the smallest functional detail is reminiscent of Kahn’s own obsessive care for design. “We’ve literally had to get inside of Kahn’s mind,” Kalomiris explains. She describes studying every scrap of planning that Kahn left behind. His vision was grand: a building that would provide the best possible viewing experience and still leave spaces for study, fulfilling the Center’s educational goals.

In a way, the building is the Center’s greatest work of art, a masterpiece whose original materials are part of its ethos. As we continue along the fourth floor, Clement and Kalomiris lift up a strip of wood from the floor to reveal travertine underneath. “It’s less expensive and less effort to replace travertine tiles than to repair them,” Kalomiris gestures to the cracks and worn edges, “but our entire mission is to conserve.”

This notion of conservation extends even to the layout of the galleries and their relationship to the art they contain. The 1998 renovation project divided the fourth floor’s Long Gallery, but the new renovations will reopen the space. It will be filled with salon-style hangings—dense, floor-to-ceiling painting displays, instead of the widely-spaced displays common in modern museums—and will no longer be subdivided. The change will allow the display of a greater number of works. The fact that so much of the Center’s collection has been destined to a life of sitting in storage is perhaps a fundamental pitfall of all art museums: art calls to be seen, yet buildings are inevitably constrained by size and contemporary standards of display. The renovations will allow the YCBA to escape some of those constraints. At the east end of the Long Gallery, a new Collections Seminar Room, similar to the current Study Room on the second floor, will allow students and visitors to work closely with individual prints, drawings, and rare books.

Even while closed, the Center remains dedicated to sharing its work with the public. It recently lent works to the Yale University Art Gallery, the Art Institute of Chicago, and Metropolitan Museum of Art. In conjunction with the release of its recent book co-published with the School of Architecture, Louis Kahn in Conversation, the YCBA has also organized lectures at Yale and at the upcoming New Haven International Festival of Arts & Ideas this summer. Linda Friedlaender, the Center’s curator of education, has continued to oversee Artism, a weekend art program for children on the autism spectrum. And the Center’s student guide program has kept up its weekly training sessions.

We descend the stairs and find ourselves once more in the lobby. Stepping over blue tarp, I think of director Amy Meyer’s words that the conservation plan the Center has published is a “living, breathing document.” Never before has it felt more appropriate to see the YCBA as a living, breathing building, one that has reached another critical point in its lifespan.

Catie Liu is a freshman in Ezra Stiles College