Ruby slowly peels the tape off her canvas, exposing turquoise and red between the stripes of black running down the painting.

“I don’t usually use black because it seems too harsh, but this time it seemed right,” she says.

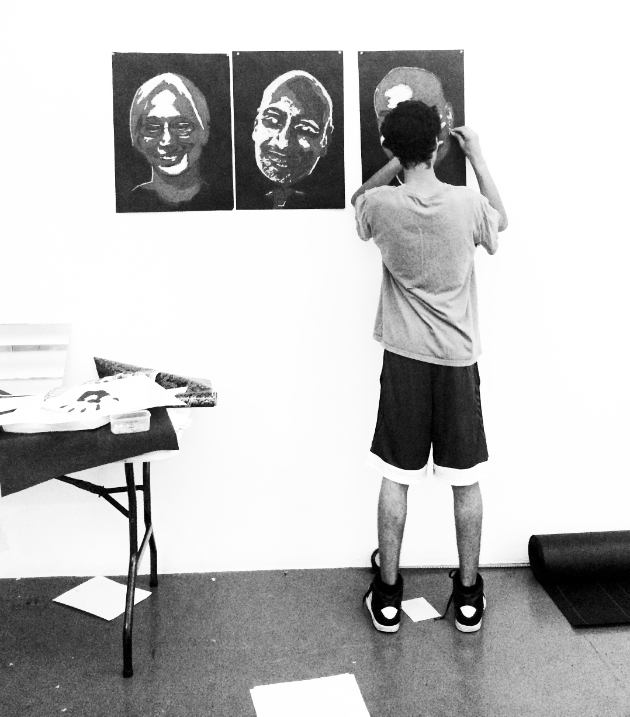

Ruby is one of eighteen New Haven high school students of color participating in Artspace’s fifteenth annual Summer Apprenticeship Program. Artspace is a nonprofit in New Haven’s Ninth Square neighborhood that connects emerging artists with audiences in the New Haven community. Every year brings a new topic for the apprenticeship program, and this year the aim is to include the young participants in a growing conversation on race in the American justice system. For three weeks in July, the students take over the gallery and turn the exhibition space into workshops. Some students were encouraged to apply to the Artspace program by teachers at their schools. Others saw the program advertised on the street. On the application form, students were asked to explain their interest in the program and whether or not their family had any personal encounters with the criminal justice system. Many of them said yes.

Throughout the summer, I worked in the offices of Artspace and watched the students influence the rhythms and energy of the building. Earlier in the summer, a busy day at the gallery often meant three visitors over the course of one afternoon. Now, at the end of the summer while the exhibition is up, the gallery attracts around twenty people each day.

The students worked with Aaron Jafferis and Dexter Singleton from New Haven’s Collective Consciousness Theatre on poetry, songs, and skits. Lead Artist Titus Kaphar, who received his MFA at Yale in 2006, instructed students in visual art. Kaphar’s own work draws on and reappropriates the art historical canon, often to explore themes of racism and black experiences.

“The thing I am good at, if I’m good at anything, is helping people to take the seed of an idea, and water it, and grow that into a larger project,” Kaphar says of his teaching approach. Over the course of the program, the teenagers speak with ex-convicts, visit a level-four correctional facility, and learn about the history of racism and the criminal justice system. After each activity, they return to Artspace to process their experiences through art.

Before coming up with the idea for her painting, Ruby recalled a day when she had gone straight from a correctional facility to her job at New Haven’s Union League Café. A morning defined by deprivation followed by an evening submerged in excess. The next day, she approached Kaphar with a burning idea for a new direction in her art. At the workshop, Ruby’s piece was bare except for a wash of indigo blue with turquoise squares here and there. She mentions the unexpected similarity between her trip to the prison and her job as a waitress. In those spaces, customers and prisoners both expect silence from her. She and Kaphar discuss the parallels between the men behind bars with whom she was not allowed to talk, and the men at tables, whom she was supposed to serve silently. He suggests “dichotomy” as a word to formulate her ideas.

“Yeah! Like between these two worlds,” she says.

“Absolutely,” he replied. “Art is made in that space in between.”

In 2013, Kaphar created The Jerome Project, a series of ninety-nine portraits of men in the prison system who share the historically black name of his father. The students’ show shares the same name as his exhibit and culminated in the joint display of their work beside that of established artists. Kaphar’s work has always focused on themes of racial disparity, but only within the past year has it earned attention for its message.

“A lot of people ask, ‘Do you think that your art can, like, change the world in a way?’” he said. “I don’t think that in general people walk up to a painting, and their lives are changed. I don’t think that that’s what happens. But I think that the kinds of conversations that happen around paintings—those can have an impact on society.”

On the night of the student opening, Ruby’s piece hung on the wall—the turquoise background now held concentric squares of red, purple, and grey. The black lines contrasted starkly with the other warmer colors. People trickled in before the show formally opened. By the time the students were performing the poetry, skits, and songs they had created, the room was full.

From the front desk, I watched a crowd that far exceeded what I had come to expect at Artspace events filter through the galleries. For hours, some four hundred people from across New Haven gathered together, murmuring as they lingered over Ruby’s piece and over others, their voices rising in discussion as they left.