The woman I’m interviewing reaches across the yellowed plastic table and takes my chapped hands between her own. I’ll call her Lucía. She is middle-aged, with creases around her eyes but girlish dimples on her cheeks. We are sitting in a dimly lit café on the edge of the sprawling slum, or villa, where she lives in Buenos Aires. I have just asked if she misses her home in Peru. It’s June, winter in the Southern Hemisphere, and she pulls her thickly knit sweater tighter around her middle. “De vez en cuando,” (Sometimes), she says. “Do you miss yours?” Sí, I reply. The tip of my nose tingles the way it does before I am going to cry.

I had lasted through only three weeks of classes about Argentinean infant mortality statistics before I quit my study-abroad program in Buenos Aires. Instead, for two months, I walked the city’s narrow cobblestone streets from barrio to barrio. Recoleta, Palermo, Almagro, Abasto, San Telmo. Broad-leafed palms dripping flowering vines. Walls painted with pink and purple nymphs. Parks filled with roses and patchy grass and very small kids who were very good at kicking soccer balls. And everywhere, strange, faded Spanish colonials and tall, quiet apartment buildings whose walls, I was sure, had harbored yesterday’s militants and their torturers.

I made friends in bars, in chamber-music classes, and on the bus. But I had promised my time only to myself, and I often turned down plans in order to sit in hundred-year-old cafes in the late afternoon where the light from stained glass windows cast colored diamonds on the marble tables. Crossing the noisy street near my apartment at dusk, I would sometimes feel a sudden tightness in the pit of my stomach. I was far from home and about to cook another omelet in a dark kitchen alone. But I could shake off my gloom by remembering that here, I had chosen independence. I could transform loneliness into alone-ness.

The days got colder and dusk fell before dinnertime. More and more, my unplanned hours seemed to expand frighteningly. Hoping to feel productive and useful, I joined a volunteer team at an NGO. I would work in the office and, once a week, help give workshops about healthcare and rights to migrant women like Lucía who lived in the villas of Buenos Aires. During my time off, I planned to interview some of the women about their access to healthcare as part of my senior anthropology project at Yale.

On a Wednesday evening, I followed the other volunteers to Lucía’s home in the villa, where we were to lead the workshop. Dim light from an unshaded bulb on the ceiling illuminated the single ground-floor room. Twenty-odd women leaned against stained, unpainted walls or settled on the sunken couch and overturned buckets on the concrete floor. Another volunteer made introductions and began to explain that under Argentina’s Law 25.271, migrants have the right to free healthcare, education, and adequate housing. “But there is discrimination against us everywhere,” a stooped, older woman said, stepping forward. Others said they envisioned a future when making an appointment at the local public clinic would not mean waking up at 4 a.m. to get in line, and ambulance drivers would no longer refuse to enter the villa out of fear. Some nodded along, but most were already chatting amongst themselves and scolding one another’s toddlers. Realizing that it was late and that the group was losing energy, we packed up and promised we’d discuss the issues further the following week.

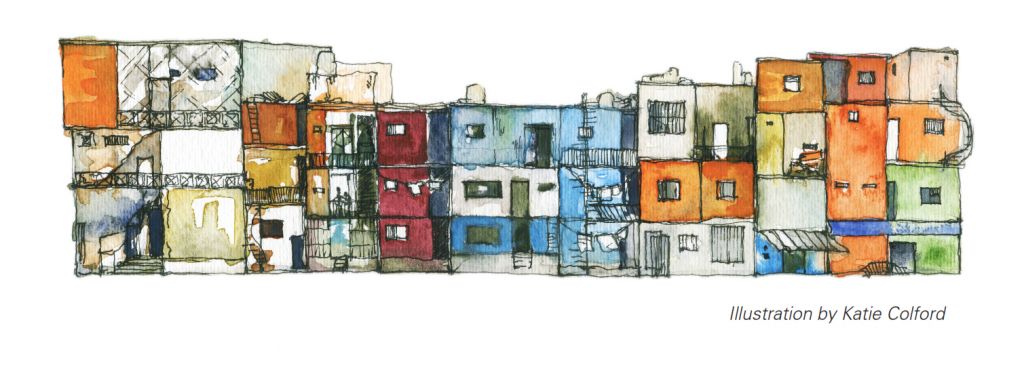

I shivered as we walked back to the bus stop along one of the narrow, unpaved streets. Dinnertime. The spicy smell of grilling meat mixed with something rotting. A maze of slender buildings, three and four stories, jumbled stacks of colored boxes rising on either side of the road. Young men outside small restaurants blasting music and stands with Quilmes beer signs. Skinny dogs weaving between legs. Dogs sprawled on their sides, rib cages heaving. A woman stepping from an open doorway and slopping a bucket of grey water into the street.

By the time I got off the No. 92 bus back in “the rest” of Buenos Aires, I felt weak. I was safe in my air-conditioning, safe in my clean cotton sheets. But I was sweating right through them. Some roll of the dice had dropped me in the right side of Buenos Aires on a comfortable mattress in a freshly painted apartment. I knew that if I thought about where I had just been I would cry, so instead I thought about what I was doing there. But I was hardly the right person to be teaching these women about their rights in Argentina. I, who could barely remember the names of the Argentinian presidential candidates, who still felt like a third-grader trying to read the news in La Nación and Pagina 12 each morning. And on top of all this, I wanted to take these women’s stories and share them with a few students and professors who spoke a different language in a different hemisphere.

I forced myself to take deep breaths as I sat in the NGO’s office that week, working on posters for our next workshop and researching Law 25.271. Taking the train back to my apartment at rush hour, I couldn’t suppress the sense that everything I was doing was wrong. At night I ate alone so I wouldn’t have to answer my friends’ questions about my work. I was too embarrassed to email my advisor at Yale to ask for help.

I assured my supervisor at the NGO that everything was going well, but when we returned to the villa for our second workshop, I felt the bile rise in my throat. I had woken up that morning with my stomach churning. We were finally here, and the buildings were too close together. Motorcycles, loud bass beats, and human shouts competed in the dark. I forced my gaze down and saw chicken bones in the mud. I pressed two fingers to the pressure point on my wrist to keep the nausea under control as we walked inside Lucía’s house, but the scent of baking bread was overwhelming. As Lucía offered the other volunteers rolls off a baking sheet, I yanked the metal door back open. Hands on my knees, I dry-heaved in the street. Several yards away two men carrying a mattress up a ladder to a second-story landing stared at me. Colorada! they called. Redhead!

I snuck back inside and whispered an apologetic excuse to Lucía about food poisoning. She placed her hands on my shoulders, led me to the couch, and handed me a roll. Lying down and biting into the warm bread, my breathing eased. A middle-aged woman perched on the arm of the sofa and introduced herself as Soledad. She began to rub my ankles. “This is what my oldest daughter likes,” she said. “Does it help?” As the other volunteers hung up the posters I had made listing the clauses of Law 25.271, I stayed on the couch with Soledad. Thinking it was safe to open my mouth again, I asked her where she was from. “Lima,” she said, the capital city of Peru. Now she was Lucía’s neighbor. “Lucía knows all my secrets!” she said in a false whisper. “Last night I came home at midnight and she was scolding me.” We both looked over at Lucía and laughed.

That night I smiled at everyone on the No. 92 bus. Helping to give the workshops and starting my anthropology project were things I could actually do, I realized. With her hand on my ankle, Soledad had given me the care I hadn’t been able to admit I needed

The next day I asked my supervisor at the NGO for advice on drafting a list of questions for the women who came to our workshops about how they understood their right to healthcare in Argentina. I emailed my advisor at Yale and held practice interviews with my friends. “When did you arrive in Argentina?” I asked a friend as she sat at my kitchen table. “When was the last time you saw a doctor?” “Do you know that you have the right to free healthcare as a migrant?”

The next day I asked my supervisor at the NGO for advice on drafting a list of questions for the women who came to our workshops about how they understood their right to healthcare in Argentina. I emailed my advisor at Yale and held practice interviews with my friends. “When did you arrive in Argentina?” I asked a friend as she sat at my kitchen table. “When was the last time you saw a doctor?” “Do you know that you have the right to free healthcare as a migrant?”

Over the next month, I interviewed Lucía, Soledad, and three other women in the café on the edge of the villa. I hugged Soledad when she walked into the café in July. As she sat down, I asked about her daughter who has just turned eleven. “The birthday cake we made was so big that Lucía had to help me carry it!” she said. She asked me how my weekend was, whether I had friends there, or a boyfriend. “No,” I told her, men take too much time. Soledad smiled and rolled her eyes. “Men take time because you have to explain everything to them,” she said. “I know,” I said. “They don’t even understand themselves.” She agreed. “You and I, we see everything. Even what we wish we didn’t!”

In one of my last interviews, I turn on my voice recorder and ask another woman when she came to Buenos Aires, and whether it was hard for her to adjust to living here. She tells me that when she first arrived ten years ago, she cried every day for her mother back in Bolivia. “I cried so much I thought I’d be sick,” she says quietly. She pauses and I don’t interrupt. “You know,” she says finally, “I haven’t talked about this in a long time.” As I settle my elbows on the café table, it occurs to me that as an anthropology student, at least I can give her this. By listening, by trying to understand, I can show her that I care. “I cry a lot here, too,” I say. “But it’s different for you,” she replies, raising her eyebrows. “At least you know you’re going home.”

*The names of the subjects involved in the research project have been changed to protect the subjects’ confidentiality.