The magician slowly slices the grapefruit in half with a large knife. He pries the halves apart, juice running down his hands. Wedged in the center of the grapefruit is a dollar bill, which he was holding just seconds before. The audience around the table applauds, enjoying the opening act of a nightlong dinner spectacle. Alone in the kitchen, the chef and mastermind of the evening quietly prepares the first course of the meal.

Every Friday night, junior Abdel Morsy cooks an elaborate dinner for twelve people. Sometimes the invitees know each other; often they do not. For one evening, they sit around a gleaming wood table at what Morsy calls “Stickershop.” (The location, he insists, must be kept secret.)

Morsy doesn’t formally promote Stickershop—it’s a purely word-of-mouth phenomenon. He invites most people personally, but others email him in the hope of getting a seat at his table. He’s also invited his Uber drivers, train conductors, and barber.

The premise of Stickershop is that guests pay not for a meal, but for an intricate sticker that Morsy’s graphic design team creates each week. It’s a way to avoid the legal restrictions of being a restaurant, but Morsy says that it’s also the celebration of an art form “as lowly as the sticker.” His humble stickers certainly aren’t cheap—each has a “suggested donation” of twenty to sixty dollars, though Morsy is willing to take a loss per head if someone cannot pay in full.

Behind me, a white floor-to-ceiling bookshelf holds elegantly arranged objects: knuckles of ginger, a row of glowing onions, two packages of ramen noodles, an army of white ceramic bottles, a hefty pumpkin, a lone jar of anchovies.

The food is the centerpiece of the project but not its essence. “Every artistic expression is valid at the dinner table,” Morsy says. Each night begins with a short performance—music, magic, or another art form. The magician performing the grapefruit trick was a Yale student and a friend of Morsy’s from the Yale Magic Society.

A square of votive candles flickers in the middle of the table. Behind me, a white floor-to-ceiling bookshelf holds elegantly arranged objects: knuckles of ginger, a row of glowing onions, two packages of ramen noodles, an army of white ceramic bottles, a hefty pumpkin, a lone jar of anchovies. On the other side of the room, Morsy is bent over the kitchen counter. He is a flurry of motion, whirling from stove to sink to fridge, and then utterly still, garnishing a row of twelve identical soups.

He does not look up as the magic show continues, but silently concentrates on the work before him. He has an intense air—eyes framed by round tortoise-shell glasses, a dark beard and moustache, hair pulled back into a tight bun—and an obsessive zeal about his work at Stickershop. “If I fuck up a dish on Friday, all Saturday I’m redoing that dish,” he says. “I’ve pulled all-nighters cooking during exam period.”

He talks about his work at Stickershop with gravitas. “We’re challenging the conventions of a dinner,” he announces as he welcomes guests. He describes Stickershop with the language of a self-fashioned foodie out to make a mark: “collective artistry,” “radical localism,” and the creation of “memorable experiences of the highest standard.” The endeavor is all Morsy does outside of classes. “Not just a project,” he declares, but the thing to which he wants to commit his life.

I first heard of Morsy via a friend who raved about a dinner “an upperclassman” had prepared on a weekend retreat for the Urban Improvement Corps—another of Morsy’s extravagant meals. For the next few weeks, I heard bits and pieces about a mysterious Yalie who made restaurant-quality dinners at an off-campus apartment. Eventually I tracked him down, and at his request we met at Blue State late one night. I circled the place a few times before a man who had been sitting near the door pulled off the hood of his Baja hoodie and I realized it was Morsy.

Though working only a few feet from the table, he exists in another world.

Morsy studies cognitive science at Yale but has been cooking seriously since he was a teenager. Originally from Alexandria, Egypt, he has worked at an array of restaurants, most recently at an izakaya in Japan. During a gap year before college, he struck an unusual deal with families in over fifty homes around the world using the travel site Couchsurfing: if they let him stay for a few nights, he would make them an extraordinary meal. Working with whatever appliances and resources were available, he “adapted very quickly to constraint.”

At Stickershop, he has “two working burners, not even a standard-size sink, [and] a half-size fridge,” but also his magician’s flair for making “something out of nothing.” The limited set enhances the drama of his dinner-as-performance.

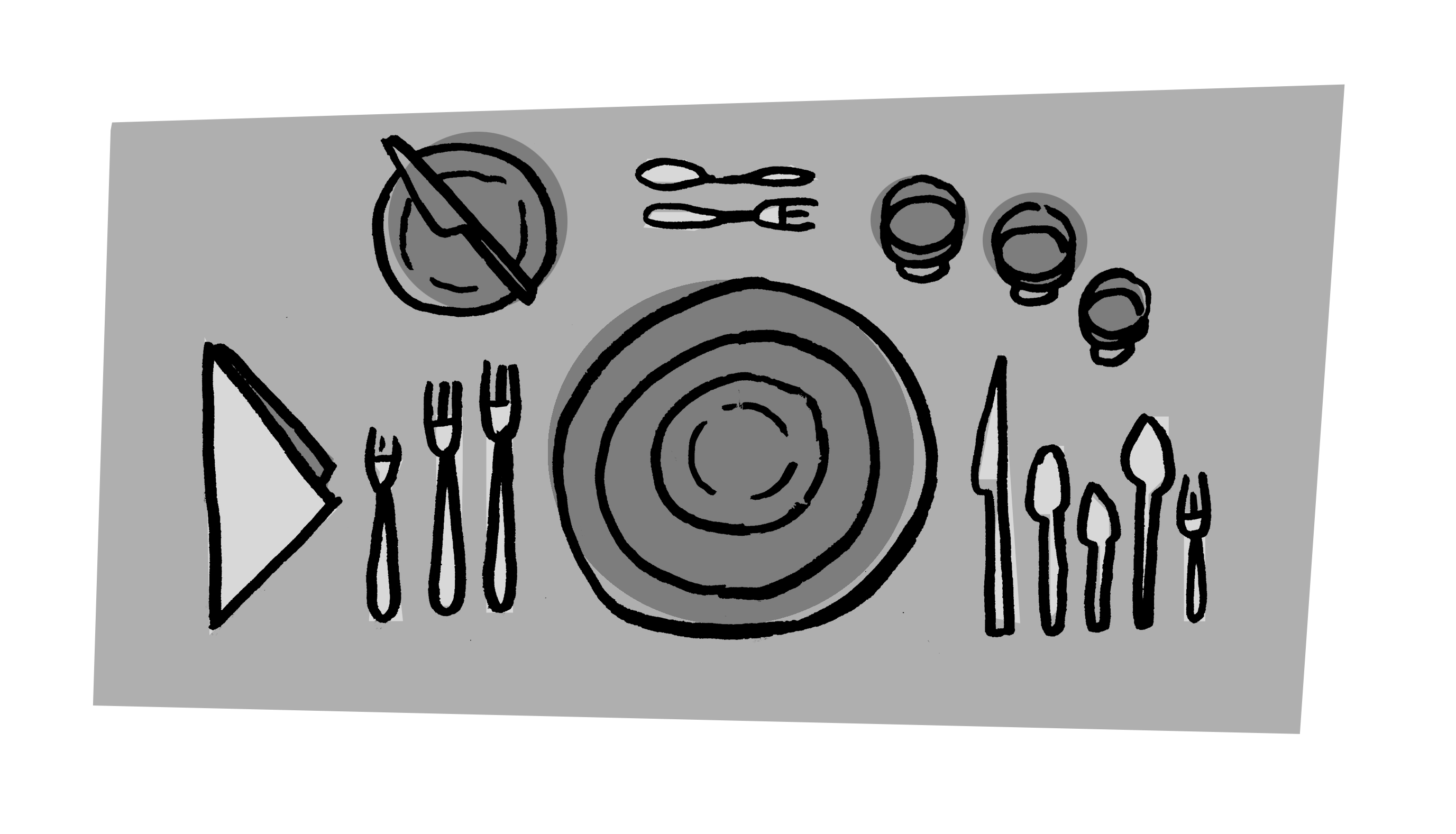

The first course arrives: a covered white ceramic pot beside a hunk of homemade baguette on a wooden platter. I open the lid to find a roasted pepper soup. We all suspend conversation as we dip our bread. The soup appears simple, but Morsy reveals that it’s made from thirteen vegetables, including a ghost pepper. The soup is smooth and sweet until I taste its powerful spicy kick and have to rip off another piece of bread.

Out comes the second course: soy-braised pork belly with a caramel-miso-cinnamon glaze, served with a pickled vegetable and pear slaw and paired with a Goose Island wheat ale.

As we dig into the tender pork, happy groans echo around the table. “Every meal after this is not going to be the same!” someone laments. Morsy glances up from the kitchen and grins, filling fluted glasses with mango lassi provided by The Lassi Bar, a Yale startup.

Morsy ferries out the third course: long black boards with truffle arancini (risotto balls) served on a smear of spinach puree. By the time the next course arrives—dry-aged rib-eye with a red wine and raspberry reduction sauce—it seems impossible to eat more. But we do.

Here, Morsy is the star, and even when he’s quietly removed from his audience, it’s impossible to forget this.

As the hours pass, our conversations grow louder and more animated and the votive candles go out one by one. In a dark corner of the kitchen, Morsy sweeps a blowtorch over a row of glass jars, toasting marshmallows for desert. Four hours into the dinner, his concentration is as intense as ever. Though working only a few feet from the table, he exists in another world.

For the final course, we are served “Dirt” in glass jars: a rum- and coffee-based chocolate mousse, topped with salty, hot figs and a homemade marshmallow infused with white chocolate liqueur and chestnuts.

Around midnight, the dinner winds to a close. Morsy is weary but radiant. “If you Google ‘runner,’ the third suggestion is ‘runner’s high,’” he says. “If you type in ‘chef,’ there’s no ‘chef’s high.’ But I run, and I know the chef’s high is so real.” The fervor is a little much, but his pride is genuine.

Stickershop flips the dynamic of an ordinary restaurant, in which servers bring out dishes to patrons who will never meet the chef, never witness the sweat and imagination behind the meal. Here, Morsy is the star, and even when he’s quietly removed from his audience, it’s impossible to forget this. “How do you know Abdel?” people ask as their plates are cleared each round.

Correction: an earlier version of this article referred to the pop-up as “The Sticker Shop” it is called Stickershop.