I’m eyeing a ten-dollar bottle of eggnog, thinking will I, but half-heartedly at best, because I will, and I do, and that’s the story of how I end up spending thirty real American dollars on eggnog. The eggnog, advertised as “old-world” and “small-batch,” comes in oblong, glass bottles. They’re recyclable. The eggnog’s only available in November and December, if it’s not already sold out. The purveyor, Arethusa Farm Dairy, believes that you don’t just let eggnog sit on shelves, in cartons. To relegate Arethusa Dairy products to the back of some supermarket refrigerator is to desecrate not only the food but also the philosophy undergirding it, the gastronomic values that might justify your shelling out thirty bucks at the year-old Chapel Street Arethusa Farm Dairy retail outlet. Dairy can be an art in the way Dutch Golden Age portraiture is, in the way haute couture is, and if there are any two men who aspire to the art of dairy, they are George Malkemus and Anthony Yurgaitis.

George Malkemus and Tony Yurgaitis are not, strictly speaking, dairy farmers. When Tony and George aren’t moonlighting as the owners of Arethusa Farm Dairy of Litchfield, Connecticut, they are executives at Manolo Blahnik International Limited, the manufacturers of the eponymous shoe made famous by Sarah Jessica Parker during her run on Sex and the City. This is all to say that Tony and George don’t come from a lineage bovine; in addition to their careers as fashion executives, the men are lifelong partners. In 1999, having discovered that the plot of land across from their country home in Litchfield was being converted into tract housing, they bought all 350 acres of that abandoned farmland. All that trouble, just to protect their view.

The couple did a bit of research. They surfaced old deeds and went to the town registrar. Lo and behold, theirs was not just any property, but rather the site of a historic farm: Arethusa, named for a rare species of orchid that once bloomed there. On went the light bulb, and a second career emerged. Arethusa rose again. “We saved this farm,” Tony Yurgaitis tells me over the phone, his voice avuncular but pointed, as if debating with a small child. “This farm that has such an important history in our community.”

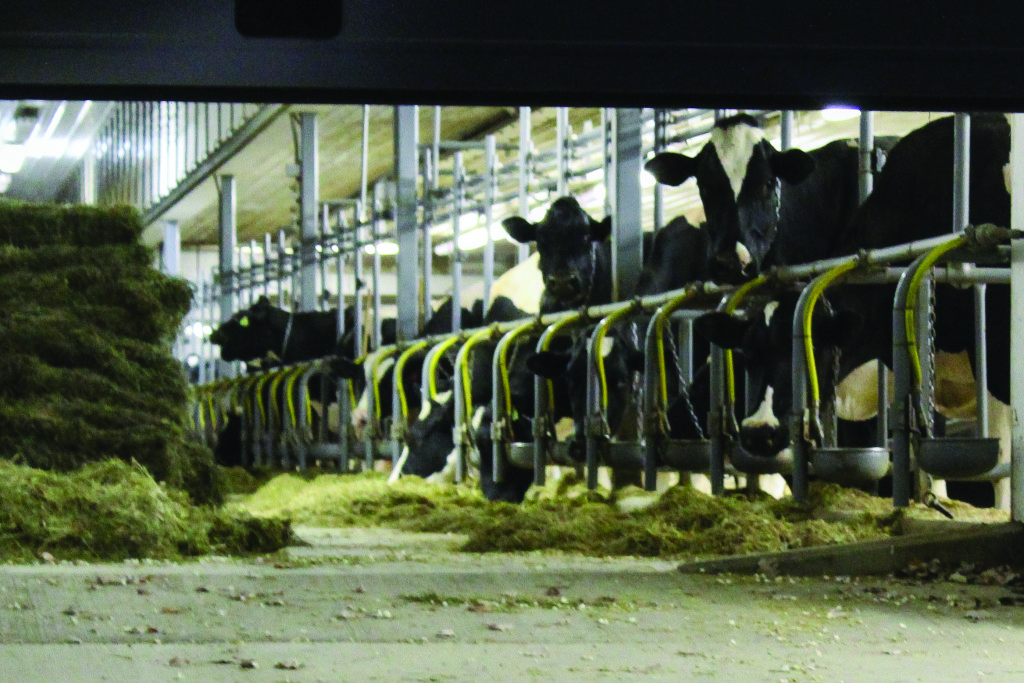

They erected a barn, wide and white, and as big as an airport hangar. The floors are kept spotless. Over fifteen years, five cows became three hundred: Jerseys, Holsteins, and Brown Swiss. Their tails are washed, conditioned with Pantene Pro-V, and blow-dried daily, as the staff will tell you on a Saturday public tour. A decal reading, “Every cow in this barn is a lady, please treat her as such” hangs above the stalls. Yes, what you’re looking at has that farm sensibility about it, but at the same time, it’s the sort of place that makes you want to come back in the next life as a cow.

About ten years after opening the farm, Tony and George bought the old firehouse on Route 202 in nearby Bantam. It became their first retail and production outlet. Soon, they bought the general store adjacent to the firehouse and opened Arethusa al tavolo, a farm-to-table restaurant now ranked among the top 100 restaurants in the nation by OpenTable. In 2013, the couple made a third purchase in Bantam, just across the street, when Shannon McMorrow, the proprietor of the Bantam Coffee Shop, decided to become a phlebotomist and sold Tony and George her space for $325,000. This spring, her styrofoam cup joint was reopened as Arethusa a mano, a café serving Italian-style espresso and light lunch fare.

That’s the triptych of Arethusa Farm Dairy in Litchfield County: the farm, the restaurant, the cafe. “The community really supports us,” Yurgaitis said. “It’s always great to see the lines out the door. We’ve become a destination not just for locals but people throughout the Northeast who’ve discovered our products.”

And, to a point, members of the community agree. “They have a good reputation in the area, an excellent reputation actually. They’re always busy,” said Cameron Bove, an organic farmer and librarian, who supplies Arethusa al tavolo with tomatoes, specialty cooking greens, salads, edible flowers, celery root, and beans. “They support a lot in the community. For example, I know they support the [Oliver Wolcott] Library, they certainly support a lot of school fundraisers. The Girl Scouts. You see their name in a lot of places.”

Which brings us to New Haven. According to Yurgaitis, Arethusa had been considering expanding beyond Litchfield, and when Yale University Properties approached them and offered a prime spot on Chapel Street, they couldn’t turn it down.

John and Karen Pollard, who live in Middlebury, Connecticut, have been doing New Haven retail leasing on Yale’s behalf for about twenty years. They knew the Arethusa story. John explains, “Karen saw what they were doing and felt like it would be an excellent addition to New Haven’s offerings of great, Connecticut, quality products.” Connecticut-based quality is a big deal to the Pollards.

It was the Chapel Street aura that appealed to Tony and George: the brick sidewalk, the dignified proximity to Yale, the hauteur. “As soon as I saw it, I thought ‘This is what we’re about,’” Yurgaitis explained. To boot, the space was jeweler Peter Indorf’s former home. The clincher? The Chapel Street outlet is less than an hour away from Litchfield, which allows Arethusa to uphold its commitment to local, artisanal production, with goods delivered from the Bantam outlet two to three times a week. “It’s just not far. Plus New Haven is a much bigger city than Bantam, which is so seasonal, but in New Haven, where the population is so much bigger, the business is more regular.”

Over fifteen years, five cows became three hundred: Jerseys, Holsteins, and Brown Swiss. Their tails are washed, conditioned with Pantene Pro-V, and blow-dried daily, as the staff will tell you on a Saturday public tour.

The Chapel Street location is almost identical to the original Bantam storefront, both with respect to design and comestibles. But even though New Haven is close enough to receive regular shipments of fresh dairy, it feels a world away from the bucolic pastures depicted on the Arethusa labels. The aesthetic brings customers into a world where cows graze peacefully, untroubled by human worries. The retail locations are très white. White walls, white hydrangeas, white light. The walls are lined with black and white photos of Jersey cows. The ice cream flavors are listed in chalk. The floors are checkerboard linoleum. “Sterilized” comes to mind. As if dairy farms didn’t smell of, I don’t know, cows or manure or rot or any of the other pungencies you get when you bust out seven thousand gallons of lactation a week.

“Going to New Haven we had to really educate our staff there, because people didn’t know about Arethusa or our story,” says Yurgaitis. “We have to be able to include New Haven, give them as much support as we give the Bantam staff.” For example, all new staff members get to tour the farm.

On such a tour, you see prize-winning cows, vats of 4 percent butterfat milk, round-the-clock farm staff. Maybe, if you’re not an employee but rather one of Arethusa’s patrons, you drive to al tavolo, examine the ceramic dishware from Puglia, Italy. Maybe you order a Stumptown latte at a mano. Maybe you’re driving a Mercedes C-Class.

And the staff? Well, I suppose they just go back to New Haven, sell these pints of creamy country goodness. But this is merely conjecture. I couldn’t get an Arethusa employee to talk on the record.

—

For the sake of owning up to my journalistic non-integrity, I’ll put it bluntly: I’m a big fan of the Arethusa products. Like Karen Pollard, my favorite flavor of Arethusa ice cream is Sweet Cream with Dark Chocolate Chunks. Their plain yogurt is not thick, but rather tangy and light in a way you wouldn’t expect. Who knows. I can’t write about food. The point is: The cheeses are great, the chocolate milk is great, and the ice cream, well.

But in the words of Barbara Putnam, a longtime Litchfield resident and food activist, however, “It’s not just about ice cream.”

But even though New Haven is close enough to receive regular shipments of fresh dairy, it feels a world away from the bucolic pastures depicted on the Arethusa labels.

Here’s the trouble: there was a time, not so long ago, in fact a time I remember, when driving West on Route 202 there wasn’t a C-Class in sight. Ice cream in Litchfield County meant Popeye’s or Max’s or Nellie’s, three scoops of blue Cookie Monster in a sugar cone that smelled faintly of formaldehyde. Now Bantam is little more than an Arethusa strip mall. Start your morning with a hand-rolled salt bagel, lunch on lump crab and taro chip salad, maybe some seared veal sweetbreads, and enjoy an ice cream on your way out of town.

Yes, there’s a wistful anger that comes with describing gentrification, but what I’m talking about isn’t gentrification in the obvious sense. Putnam acknowledged that Tony and George “are very engaged in the community and generous to local nonprofits who request their support. Every time I work at the soup kitchen, the fridge is full of milk that they have donated.” Lisa Hageman, a lifelong Litchfield County resident who runs this soup kitchen, says she no longer has to buy milk and can count on Arethusa donations “99% of the time.”

So let’s be clear. George and Tony—good guys. Sweet guys. In a way, Arethusa put Bantam on the culinary map. Putnam notes that the community itself looks upon Arethusa favorably. And, most critically, to suggest that Arethusa hasn’t brought bodies and capital to Litchfield County would deny the simple facts of the matter.

And yet, to understand the nuance of the problem of Arethusa Farm Dairy, a little Litchfield context is necessary. Tony and George are weekenders. Their white-paneled Neoclassical estate facing the farm was, before Arethusa, used for Easter and Labor Day and convenient weekends in between. During the workweek, they are Manhattan residents.

There’s a lot of that in Litchfield. Susan Saint James, Mia Farrow, and Anderson Cooper have all weekended there. Cameron Bove, the organic farmer, acknowledges the weight of this fact: “[Arethusa] caters to the New Yorkers, the second-home community, but they employ a lot of people here.”

In Bantam, not so much. Though a borough under the governance of the town of Litchfield, Bantam has an identity entirely its own. It isn’t blue collar in quite the same way that Reading, Pennsylvania is blue collar. But everything is relative, and though permanent Litchfield residents are not nearly as wealthy as the weekend population, Bantam is still a much poorer town. The median income for a household in Bantam is $32,167; in Litchfield, that amount is $58,418—just a few thousand above the national median. To make it topical: Trump dominated in Bantam and won only by a small margin in Litchfield.

The drive between the Arethusa cows and the old firehouse where their milk products are sold takes only fifteen minutes. But, as Barbara Putnam notes, that distance is more symbolic than one might assume: “There are rich weekenders who can afford to eat in [Arethusa al tavolo] and buy their ice cream, and there are longtime locals who can’t.” Putnam links this tension to the discussion of wealth inequality that has dominated so much political discourse in recent months.

“There are rich weekenders who can afford to eat in [Arethusa al tavolo] and buy their ice cream, and there are long time locals who can’t.”

Trish Lapidus, a senior citizen who’s lived in Bantam for just four and a half years, nevertheless feels that something has changed. “It does seem to have changed,” she tells me. “Five years ago, Bantam was a little more down home. Things weren’t as expensive. Now I think Bantam—don’t get me wrong, it’s beautiful, it’s wonderful—part of it is sort of rich-focused. There are two restaurants that no ordinary person can afford. Mind you, I admire those people, but it’s just out of my price range.”

To be fair, there’s been no overt clash between Bantam and Arethusa or New Haven and Arethusa. No protests of gentrification, no boycotts by the ranks of the food-conscious. For now, everything remains beneath the surface, simmering, pasteurizing, if you’ll excuse the pun.

“I mean those cows cost $400,000,” Lapidus continues. “I live on $1100 a month. It’s a different world. I look around and I think, that’s a different world.”

—

Last weekend, I went to Arethusa on Chapel and paid $4.50 for a huge cone of Sweet Cream. As luck would have it, Tony and George were there, and I went over and said hello. George was rearranging pints of ice cream. Tony was telling me how he wants to get the word out about the new grilled cheese sandwiches. Tony was wrapped in a winter coat, George had a smile as wide as a banana. I ask one of the employees if the couple often visit the store. “Once in a blue moon.”

It’s difficult to watch George rearranging those pints, clad in a Merino wool sweater or whatever and the customers sampling new permutations of blue cheese or debating the merits between the 1% or 2% milk and to be reminded of Litchfield. Or New Haven, for that matter. The store is reminiscent of something, yes—but I’m not quite sure what. It is a Connecticut divorced from the one I grew up in. Yet still the bottles read, “Milk like it used to taste.”