It was nine on a November morning, the sun low in the east, and eleven stained-glass windows in the west end of the nave glowed strangely from the indirect light. The glass was mostly opalescent sky blue, but it danced as I watched: ripples of orange, yellow, and green burst from nowhere, then faded away. In one window, four pieces of red glass formed the Greek letter alpha. In another shone a red omega.

Jayne Crowley was here at Stony Creek Congregational Church to oversee the removal of the alpha window, the omega window, and four others. The windows were over a hundred years old, and their cames—strips of lead that join each piece of glass together—had warped and crumbled. A few pieces of glass had cracked. The windows needed a facelift, and Jayne was the plastic surgeon: a stained-glass artist and an expert in restoration. Later this morning, the windows would be extracted from the walls; then Jayne would drive them to her studio in nearby Branford, take them completely apart, and, over the next two months, restore them.

Jayne is 75 years old, about five feet tall, and not as strong as she used to be. She can’t lift large windows herself anymore. In February, she plans to go into partial retirement and give up major restoration jobs like this one for good. It’ll be nice. She’ll leave her Branford studio. She’ll work from home. She’ll focus on her own art, and she won’t have to deal with the physical strain of repairing heavy windows. These six in the Stony Creek nave will be the last of her career.

But right now, there was a problem. Whoever had previously installed the windows had soldered them directly to the metal bars in the opening of the wall—according to Jayne, they should have twisted wires around those bars instead. “I don’t know what idiot ever did that,” she said.

She tried to grind through the solder with a Dremel, to no avail. Then her apprentice, Francis, figured out you could cut the solder with wire cutters. He walked from window to window, snipping them loose. Francis will take over Jayne’s studio when she leaves, and in the meantime, she’s teaching him the craft of restoration. Francis likes to call himself “grasshopper” and Jayne “master.” He’s in his late sixties and wears his gray hair in a short ponytail.

Eventually, two guys wearing cargo pants and hoodies showed up. Outside, one of them climbed a ladder and began to scrape the putty around a window with his box cutter. Chunks of the stuff came showering down. Jayne, who had been inside labeling the windows with duct-tape Roman numerals, walked onto the lawn to watch.

More scraping. More showering. The second worker pushed from inside. Finally, the window emerged. The man on the ladder hoisted it with both hands, found his balance, and began to climb slowly down. The ladder shuddered with each step. He reached the grass and handed the window to Francis, who received it reverently. It was too fragile to hold flat, so Francis carried it straight up in front of him, as if looking in a mirror. Beside the open trunk of her white Volvo, Jayne silently watched him approach. Francis rested the left edge of the window on the floor of the trunk and slowly lowered the right. We exhaled: the first of six was safe.

⬖

Glass shards in cardboard boxes, glass sheets leaning against tables, glass lampshades that look floridly expensive, one large glass dollhouse with a green gabled roof—all this and more litter the floor of Jayne’s studio. You have to watch where you step. One Thursday morning in October, Jayne herself nearly kicked a sheet of glass. “Always a million things lying on the floor that don’t belong there,” she said theatrically, like it was someone else’s fault.

Jayne wore black that day: black socks, black capris, a black T-shirt. But there were flashes of color—on her shirt, three cartoon fish: orange, red, blue. On her gray sneakers, threads of orange around the ankles and at the tips of the tongues. Her short hair is golden blond, dusted lightly with silver. Her eyes are blue, and the thick plastic frames of her bifocals are sunflower yellow.

She was fixing a Handel lampshade. It was around a hundred years old and would likely sell at auction for a couple thousand dollars. A mosaic of cattails and water lilies circled the base; above them was a layer of blue pieces streaked with white, then a ring of orange. Each piece was lined with copper foil and soldered in place. A few of the pieces had cracked, so Jayne had glued them back together. Jayne doesn’t waste old glass. It often achieves rare colors that can’t be matched today, partly because glassmakers back then added ingredients like uranium and arsenic. (In the early nineteen-hundreds, some glass could be close to 25 percent uranium.) Holding a coil of bright silver solder against a soldering iron until it liquified, Jayne touched up a gap between two pieces of glass. The solder sank in and smoked. The air smelled bitter.

Lead is the main ingredient in both solder and came. I once asked Jayne if that was dangerous. “Oh, yeah. Yes. There’s lead poisoning,” she said, and laughed: a bouncing chuckle that died down gradually. The CDC says an elevated lead level is anything over five micrograms of lead per deciliter of your blood. Jayne has twenty-five. (Later, she pointed out that this likely wasn’t all from stained glass; some of it could have come from growing up around lead paint in the nineteen-forties and fifties.) She doesn’t feel any symptoms, but her work takes its toll in other ways. In November 2019, Jayne was climbing on a stool, trying to reach something on a shelf. Somehow, she shifted her weight wrong and the stool flipped over. She landed hard. It took a year and a half for her back to heal.

Jayne has been making stained glass since either 1973 or 1974, she can’t remember which. Either way, it’s getting close to fifty years. She’s one of only a handful of independent stained-glass artists in Connecticut actively restoring old church windows—Jayne estimates there are three or four others along the coastline, maybe a few more upstate. All of them are getting on in years. Some are shutting down their studios, too old to carry on. When Jayne starts working from home next year, she’ll join their ranks.

Jayne believes that the coming years could be grim for the stained-glass scene. Without studios like hers, the only places that would restore church windows would be big out-of-state glass firms that charge huge fees. Small Connecticut churches wouldn’t be able to raise the necessary cash, and so their windows—old, beautiful windows—would deteriorate. Some glass, perhaps, would crack. The paint might chip and flake. The cames might stretch and corrode, or the window frame might warp, weakening the entire structure, until at last the glass falls to the ground and shatters.

⬗

There’s a joke on Twitter about traveling back in time and giving a medieval peasant a Dorito. The punchline is they’d die. But if a nacho-flavored chip could have killed someone back then with overstimulation, I don’t know how anyone survived Chartres Cathedral. Inside are 176 windows, over twenty-seven thousand square feet of stained glass. Light pours from every wall, pooling in vivid scarlet and sapphire on the stone floor. Three massive “rose windows” blossom in concentric circles, depicting the Last Judgement, the Virgin and Child, dozens of Biblical scenes. The smallest rose window is thirty feet across. It must have been like looking straight into God’s iris.

All 176 windows were installed between 1203 and 1240. Since then it’s all been downhill, many experts think. During the Renaissance, the big-shot artists picked up painting instead of stained glass. Then the Protestants arrived and began building their supremely boring churches. Stained glass’s decline was complete: walls of divine light had fallen decisively out of fashion.

Skip to the eighteen hundreds. The British Arts and Crafts movement, in search of a style untainted by capitalism, decided Gothic architecture (and stained glass with it) fit the bill. Across the Atlantic, American artists mimicked the crafts but dropped the socialist undertones, sparking a stained-glass renaissance. Louis Comfort Tiffany’s Art Nouveau lamps and windows led the way—he’s still the one name you’d know if you knew any American stained-glass.

During the nineteen-sixties, stained glass lost sight of God. Here’s how the website for the Stained Glass Association of America portentously describes the period:

The statement “God is dead” was heard. It was time for stained glass to find a home in the secular world again. After the pessimistic “beatniks” came the optimistic “hippies” spreading eastward from San Francisco where they were rehabbing the old houses, painting them bright colors and, of course, repairing the stained glass.

Jayne was born a couple decades earlier, on the Fourth of July, 1946. As a kid in North Haven, she had no interest in art but lots in science. Her favorite toy was an A.C. Gilbert chemistry set. She’d mix vials full of chemicals, heat them over candles, and watch them bubble over. Gilbert chemistry sets, long since banned, included plenty of harmless chemicals along with some plenty harmful ones, like potassium nitrate and sodium cyanide. The company even made a short-lived “Atomic Energy Lab,” which came with, yes, uranium.

Jayne attended St. Mary’s High School in New Haven, a Catholic school. “That was probably the demise of my religion,” she told me. (About ten years ago, though, she returned to repair the convent’s windows. “I came back to haunt them,” she said.)

She studied chemistry for a couple years of college, then put her academics on pause. After a marriage and a kid and a move to New York and a divorce, Jayne ended up working at the West Haven branch of Miles Laboratories, a pharmaceutical company in the complex that’s since become Yale’s West Campus. She didn’t like it much, so after a couple years, she moved to Colorado. There, she met people who were part of a growing American crafts movement. (These were presumably the “hippies” who had killed God.) She played around with pottery, with macramé, with “all different kinds of crafts,” she said. Soon after, she moved back to Connecticut and tried stained glass for the first time.

She fell irrationally, irrevocably in love. She speaks of the decision as if it had not been a decision at all, but an event beyond her control. She told me once that the glass itself had said to her, “This is what you’re going to do.”

When Jayne first started, there were no stained-glass teachers in the area, she said. So she taught herself, a mystifying feat in a highly technical craft. Even she can’t explain how she learned everything—how to solder, how to cut glass, what kind of pliers to buy. Sometimes she visited a stained-glass store called Whittemore-Durgin, where she might have been told what supplies she needed. But the rest of it was luck and trial and error and youthful determination. She rummaged through dumpsters to find scraps of glass. Her first ever piece was a purple and blue glass jewelry box.

At the time, the switch from chemistry to glass felt like a hard pivot. But the more deeply she fell in love with glass, the more she began to see the connection. “The chemical makeup of glass is so unusual,” she said. “It’s the only thing you can transform, shape, make it molten, make it solid, blow it into a ball, and then take that ball and flatten it out again.”

In the nearly fifty years since she opened her first studio, Jayne has burned through ten studios (one of them did literally burn down), all in Branford. Now, she believes stained glass and other skilled trades—masons, cobblers, bookbinders, furniture-makers—are in decline. “All these things are falling away,” she told me. “We live in a throwaway society.”

She blames it mostly on IKEA: mass-automation makes it cheaper to buy new things, she says, than to fix old ones. But stained glass can’t yet be automated very efficiently, and the restoration of old windows is the opposite of throwaway culture. The real problem, Jayne believes, is that not enough young people want to devote themselves to the craft—the work is just too hard.

⬘

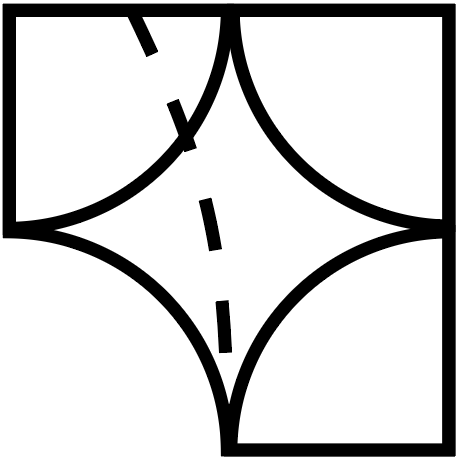

One morning at the end of October, I arrived at Jayne’s studio with a piece of paper stuffed in my pocket. The drawing on it looked like this:

Jayne was going to help me make it into stained glass. She wore a plain black sweatshirt over a red turtleneck. On her wrists and around her neck, the red peeked out from behind the black. Francis, the apprentice, was working at a nearby table and whistling.

Jayne chose a deep blue glass for the outer corners and something called “glue chip” glass for the central piece. Glue chip glass is made by sandblasting a sheet of clear glass, then coating it with animal-hide glue. As the glue dries, it “pings off,” Jayne said, taking little chips of glass with it and leaving a frosty, fern-like pattern. I told Jayne I’d be happy to pay her for the materials. She just laughed at me. “Oh, please,” she said.

Jayne cut along the lines of my drawing and traced the corner pieces onto the blue glass with a Sharpie. Then she placed the glass cutter—a tiny wheel of carbide fastened to a plastic handle—against a straightedge and dragged it toward her along one of the Sharpie lines. It made a sound like quickly ripped cardstock and left a slender score. Jayne snapped the glass with her hands; it broke cleanly. Next she made a curved score, freehand. She squeezed a pair of running pliers—which have a mouth shaped like a frown—on the score, and the glass snapped along the curve. Piece number one was finished.

I copied Jayne, dragging the glass cutter, squeezing the running pliers. It was like snapping a sheet of caramel. The edges of the glass left my fingers with an odd roughness, and I wondered if it was the feeling of tiny shards in my skin.

“You’re all set,” Jayne said, and walked away.

I didn’t feel quite set. I tried my first curved score, but, pressing too hard and moving too fast, I slipped wide of my intended line. Jayne came back and excised a delicately thin slice to make my piece its proper size. She moved more slowly than I had and held the cutter more gently.

After considerable difficulty, I ended up with four ugly corner pieces. I still had to make my center piece out of the glue chip glass. On my first three attempts, the glass snapped in half immediately.

1.) Bad:

2.) Worse:

3.) Awful:

I’d wasted at least a square foot of Jayne’s glass by then, and I was starting to feel guilty. On attempt four, I tried angling the running pliers toward the curve of the score. Behold: it broke left and cracked clean.

“You’re starting to learn the properties of glass,” Jayne told me. I felt proud.

“It’s nerve wracking,” I said.

“It’s supposed to be fun!” she replied.

My second cut was clean again. Just two left. I squeezed my running pliers, and—disaster.

I felt genuinely distraught. Why is this so hard? I thought. What could I be doing wrong? I’m wasting Jayne’s glass for no reason at all. I wanted to apologize but didn’t want to show her what I’d done. So I just stood there for a while and pretended I was making great progress.

Jayne was utterly unbothered. She cut me another sheet of glue chip glass, and I pulled myself together. Cut one was clean, but I hesitated on cut two. I’d have to squeeze the running pliers on the sharp point of the glass, rather than on a flat edge. It didn’t feel right. I asked Jayne. She came over slowly from across the room.

“I’m done tormenting you,” she said. She made a score an inch outside the Sharpie mark and picked up the grozers—a pair of pliers with a bottom jaw that curves up like an underbite—instead of the running pliers. Working from the side, she snapped her approximate score with the grozers, then made a perfect break along the Sharpie line. I’d been using the wrong technique, and she’d been letting me struggle.

On the third cut, I imitated Jayne: success.

Last one. I scored the glass, squeezed the grozers, felt it crack all at once. I held up my star to show Jayne.

“Hooray!” she said.

Jayne seemed to take pity on me after that. I needed it—cutting the glass was more exacting than I’d expected. She had Francis help me line each glass piece in copper foil, paint the foil with flux, solder the pieces together, and frame it all in came.

The next day, with Jayne’s guidance, I rubbed patina onto the solder, which darkened it from silver to dusky gray. Finally, I attached two metal rings to the frame, for hanging.

It had taken me two days to make a suncatcher the size of a large slice of bread. The edges were jagged, the foiling was shoddy, and the solder lines bulged. I couldn’t imagine making a full-sized window. But on the whole, I thought my piece was pretty. Back in my apartment, I propped it up on the windowsill, and the glue chip glass scattered the afternoon sunlight across the walls.

⬙

The glass in a cathedral window flows toward the ground one nanometer every billion years. This is beyond slow. The universe, for instance, is a little under 14 billion years old. I remember being told in middle school that glass was a liquid, but that’s only sort of true. Really, glass is something much, much stranger. If it’s a liquid, it’s a liquid stuck in time, or locked out of time: an eternal liquid.

“Glass” is not a particular substance, it’s a category of substances. Anything can be glass if its molecules are arranged chaotically like a liquid but feel rigid like a solid. Ordinary window glass is made from melted silica sand, but theoretically, almost any liquid could become a glass if you cool it fast enough. Plastics and hard candies are technically glass. You make glass by dropping a liquid’s temperature so fast that its molecules can’t crystallize into a solid—they keep flowing, only slower and slower and slower.

No one can figure out why this happens. The Nobel-winning physicist Phillip W. Anderson once wrote that the nature of glass is “the deepest and most interesting unsolved problem in solid state theory.”

Some people think glass is matter stuck between solid and liquid. They call it an amorphous solid or a supercooled liquid. Others think it’s something weirder—an imperfect reflection of a yet unwitnessed state of matter they call “ideal glass.” Ideal glass is what glass would become if its molecules had unlimited time to flow past one another, settle together, and reach the densest of all possible random arrangements. Its molecules would look jumbled but would in fact follow a mysterious, invisible pattern (a “long-range amorphous order,” scientists call it). All glass—from windows to eyeglasses to wineglasses to fiber optic cables—is slowly, slowly approaching this true glass. As far as anyone knows, ideal glass has never existed in the history of the universe. It just takes too long to form.

If you had billions and billions of years at your disposal, you might be able to catch the first glimpse of ideal glass. You might see a normal window, for instance, flow down into itself and gradually arrive at perfection.

⬙

On a table in the middle of Jayne’s studio, the alpha window and the omega window lay side by side. It was a little over a month after the windows had come down. The alpha window was whole and apparently complete—all Jayne had to do was touch up the solder and rub putty into the seams to seal out the weather. Next to it was the deconstructed omega window. Scraps of came and slabs of milky glass were piled on the table, like puzzle pieces straight from the box.

Jayne predicts she’ll finish restoring all six windows by the first half of January: all told, a two-month job. Stony Creek Congregational is paying her about fifteen thousand dollars. Exactly when they’ll be reinstalled, she’s not quite sure. Probably February. Her relationship with the glass in this church is a committed one. Around four years ago, she restored five other windows in the same nave. “It’s kind of like my baby,” she told me. “I just want to make sure they do everything right.”

Today, Jayne was working on the omega window. In the past few weeks, she had made a rubbing of it, numbered each piece, cut the cames apart, disassembled the window, and soaked the glass in water to help remove the old putty. She had spread the rubbing out on a table, and now she was fitting all the glass pieces back together with fresh came, working from the bottom right to the top left corner. She had reached a row of blue, diamond-shaped pieces near the bottom. They looked like my troubled piece of glue chip glass, but a little smaller and a lot neater.

She worked steadily, cyclically. Her cycle went like this: Set the next piece of glass into place against the came. Tap the glass gently into the existing structure with a rubber mallet. Drive a flat-sided nail into the table, flush with the edge of the glass piece, just to keep it still. Cut a new length of came. Remove the nail and press the came onto the exposed edge of the glass. Tap the came snug with the mallet. Use another nail to keep the came in place until the next piece is ready. Remove the nail and repeat.

The aim of restoration is not to improve the original window, but to mirror it exactly. Where the original window used a thicker or thinner or flatter came, Jayne did too. The omega window displayed a technique called “cross weaving,” in which the vertical and horizontal cames alternated long and short. Jayne replicated it. Molding the soft came with fingertips dark from the lead, she wove a tapestry of metal and glass.

Soon, the restored windows will be hauled up again the same way they came down. Jayne will load them in her trunk and drive them to Stony Creek Congregational Church. A man will carry one of them up a precarious ladder. The window will be slotted into the opening, where it will rest against metal bars. Thin wires that Jayne will have soldered to the came will be twisted around these bars to hold the window in place. The sun will catch the glass, and it’ll ripple orange, yellow, green. Then the other five will go back in, and it’ll be over, and Jayne will never again restore windows of this magnitude.

“It feels… fine,” she said. It feels fine to be done. Of course, after working in studios for close to fifty years, it’s sad to leave the last one. “But it’s time,” she said. Then she was quiet for a while.

Recently, Jayne hired someone to convert a shed in her yard into a proper home studio. Now it has air conditioning, heating, painted walls, and plenty of windows. “It’s so light and airy,” she said. “They’ve done a wonderful job.” When she leaves the Branford studio and moves home, she’ll spend her days in that shed making original pieces, trying out new techniques, and reveling in retirement. Her neighbors, in Short Beach, are excited for her. Some of them have asked her to host an open studio so they can see the new place. People call out to her from the street, Jayne said. They yell: “That shed is so beautiful!”

This isn’t the end for Jayne. She’s settling down gradually, like glass. It’s not yet time to call it quits—not when she can wake up in the morning, walk to her shed full of light, and work all day until the sun sinks in the west and flares in the windows one last time before it sets.

Eli Mennerick is a senior in Ezra Stiles College and Managing Editor of The New Journal.