Yale professors view him as the angel of death, Sam Burton jokes, because he visits them before they die to relieve them of their literary treasures. As the owner of Grey Matter Books, he is not just a bookseller, but a master collector for his customers. His search for fresh, intriguing books often means waking up at the crack of dawn, scouring trunks at estate sales, and traversing the state to poke around in long forgotten collections. It can lead him anywhere: recently, he found himself fishing for books in the wine cellar of a man who “supposedly killed his wife…and then committed suicide.”

Burton has worked as a book buyer for thirty years. He started at the Strand in New York City, where he jokes that you could get a job “if you knew who Virginia Woolf was.” From the Strand, Burton moved to San Francisco and finally to Powell’s in Portland, Oregon. After an interlude selling books online, which was “lonely and alienating,” Burton went on to establish two bookstores of his own, hoping to recapture an intimacy with surrounding communities that bookstores like the Strand and Powells have lost since becoming national empires. The first Grey Matter is in Hadley, Massachusetts, and the second is on York Street, nestled in the imposing shadow of Sterling Memorial Library.

The harm that the internet has done to brick-and-mortar bookstores is well-known. But they still exist, argues Paul Freedman, a professor and food historian at Yale, because algorithms such as Amazon’s are “laughable”—they will never replicate the experience of browsing. “The whole point is to emerge from the store with something you hadn’t been looking for,” he says. On a recent trip through New England, he and his wife happened upon a small used bookstore with a large collection of community cookbooks—recipes assembled and bound by small communities to give to friends and record important dishes. Freedman took home the “Rolls Royce Club Cookbook,” a cookbook created by members of a car club. The rigid categories and subcategories of online stores and research databases, Freedman speculates, would have made it near impossible to find something so unique.

“I don’t lament as many things as other people do,” Freedman insists. Freedman has faith that books are not like vinyl, destined to become vintage relics. He believes the internet’s ability to categorize material will never replace the feeling of browsing for used books or scouring through archives—what Freedman calls “the thrill of the chase.”

Burton embodies this nonchalant optimism about the fate of the used book. He does not romanticize the book trade. There are no signs in Grey Matter imploring customers to support struggling used bookstores. “I don’t feel that missionary about really anything,” Burton says. “The only thing I feel strongly about is having enough cheap books…you can get a copy of Dante for $3, or Homer for less than the price of a sandwich across the street,” he reminds me.“Mine are always cheaper than [Amazon].”

But Burton’s model is also not driven by pure economic efficiency. Most used books are “garbage anyway, or they’re just kind of bland, or common,” he says, referring to the kind of quickly recycled popular fiction that you will never see in Grey Matter. Instead, he lets his own tastes and a growing sense for the community’s preferences drive his book buying and shape the store’s selection. He has found that his taste is usually “positively reinforced” by his customers, but he also takes notes about our literary preferences. “The hunger for classics, for Latin stuff, Greek stuff [in New Haven] is pretty much bottomless,” he reports. Henry James books seem to fly off the shelves, but “I can go a month without selling a Henry James book at the other store. And you take note.”

While I was interviewing Burton, he reached back and pulled out a book of sonnets by Raymond Queneau, sliced into horizontal strips to invite the reader to make their own poems in various permutations. “This is something that, in a way, I hope I don’t sell, cause I think I like having it around.” Burton bought the book from a convicted forger, he reports with a grin. “Luckily that one was not signed.” For now, the book sits on the back wall above the check-out counter. “There’s a lot of stuff that I like having, that I’m not in a big hurry to sell, although after a couple of years, I’ll either take it home or I’ll mark it down and actually price it to sell.”

From a perch amongst the unruly stacks of recent acquisitions, a boisterous voice chimed in. “Sam is a pioneer!” exclaimed Jay Gitlin, a Senior Lecturer in American History at Yale, and a regular at Grey Matter. For him, browsing is therapeutic. It’s a chance to discover new ideas that hadn’t occurred to him and hold a piece of communal history from the collections of Yale scholars. He is grateful to Burton for helping keep print culture alive and encourages his students to buy paper copies of the books he assigns from Grey Matter whenever possible. While he does lament the passage of many used bookstores that used to line the streets of New Haven during his undergraduate days, he sees Burton and Grey Matter as “the forefront of a changing of the guard.”

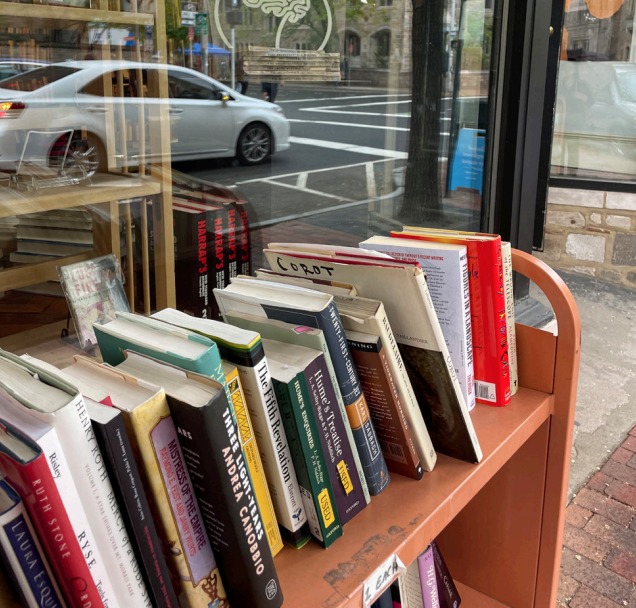

According to Freedman, there used to be a book buyer from West Virginia who specialized in buying out the collections of aging Yale professors, and it seems that Burton has largely taken over that role. Burton reserves the slim shelf facing York Street for the collections of late professors—a sort of literary gravestone. Rather than distributing these books by subject throughout the store, he keeps the collections intact and affixes a sign with the name of the professor. “My concerns are always more about getting books than selling them,” Burton muses. In recent years, he has acquired books from the collections of renowned scholars including Geoffrey Hartman and Immanuel Wallerstein.

“People like me are desperate to get rid of books…I can’t bring these books home,” Freedman tells me, pointing to his office shelves. “These aren’t particularly valuable. I’m not going to live in my old age with books piled on the floor everywhere.” This is the golden age of book collecting, Freedman claims, because there is little demand for the books being discarded.

Burton’s trips to appraise collections and buy books from people getting older and starting to downsize are often “intense and personal,” he reflects. Freedman went through this process with his parents when they passed away ten years ago; he could not keep all of their books, and instead sold them off as a collection to an estate liquidator. “They were unsellable…I wonder what they did with the 90 percent of stuff [that has] no commercial value.” Burton’s process is similar: he remembers purchasing four thousand books from the collection of J. Hillis Miller, a member of the Yale School of deconstructionist literary critics. Burton estimated that four hundred of them would sell.

Part of what keeps the community coming back to Grey Matter is a chance to inherit books from thinkers like Miller. The selection of the store takes its shape from the collections that Burton purchases. Eventually, he says, he will bring many of these books—including an inscribed Edward Said—out of storage. “I’ve had this long standing plan to have a second rare book case that will be more focused on the history of ideas, [but] Ikea has been out of this cabinet for two years. So that’s, that’s horrible.”

Walking into Grey Matter, I gravitate towards the massive philosophy section at the center of the store. Burton studied philosophy as an undergraduate and wanted the subject to have a prominent place in his sanctuary. I glance around to see what’s new: the shelves at Grey Matter look completely different from week to week. This week, there’s a beautiful hardcover set of Montaigne’s complete essays. Its colorful dust jacket and thin but sturdy pages are tempting. Do I really need to spend $15 on this right now? It’s a completely reasonable price, but I set it back down and decide to wait a few days. The next time I return, it’s already been sold. I am not disappointed: I am confident another will crop up before long.

Burton has dedicated his life to wading through this literary labyrinth—to chasing and searching and bringing the books worth saving to a community with a seemingly endless desire for them. “I’m always at least trying to guess what is going to mean something to people around here,” Burton reflects. As I browse my way through Grey Matter and assemble my own collection, I know that thanks to Burton, I am inheriting from a grand collection built from those who came before me.

—Yosef Malka is a sophomore in Morse College and an Associate Editor of the New Journal.