“The attic was a fascinating place for me,” reads a note atop six panels of navy blue linework drawings. In the upper three panels, a young boy digs around an old chest, discovering a gun, bullets, a grenade, and other military equipment. In the lower three panels, another character comes across some clothing, a vial of morphine, and a sword. The caption: “Attic discoveries—1925 and 2020.”

It seems like what the characters are really discovering is pieces of themselves; we are just not sure what. Simone Hasselmo drew these panels as part of one of their first longform comic projects in which they explore their grandfather’s experiences growing up in Nazi Germany, alongside their own experiences in medical school. As my eyes travel from panel to panel, I am struck by the unchanged expressions of innocence on their characters’ faces as time inevitably passes.

“I don’t think I would be doing it if I felt like I had a choice,” Simone Hasselmo, a Yale School of Medicine student tells me about their passion for zine and comic making. For Hasselmo, narrative art is a compulsion—one that informs and is informed by their passion for medicine. Hasselmo’s art combines the clarity and precision of comic-style minimalism with the complicated nature of their identity—leaning on humor, caricature, and the exploration of familial bonds. But narrative art doesn’t just contain Hasselmo’s identity. It informs it, too. They are able to explore their own relationships, like that with their grandfather, as well as their own queerness and femininity, they tell me. Like an attic discovery, zine-making provides a medium for Hasselmo to uncover parts of themself, to interrogate their identity. But this would not always have been possible for someone like Hasselmo.

The modern conceptualization of the zine arose first in post-World War I science fiction circles. They came to be known as an art form that combined images and writings, often self-published and created by individuals or a small handful of people. Fans of the medium would use them to share literature and ideas they were passionate about. In the nineteen-nineties, a third-wave feminist movement called Riot Grrrl expanded the countercultural significance of the zine, and centered it around the experiences of young, often lesbian and bisexual women making radically feminist punk music.

Despite how progressive the Riot Grrrl creators were, the scene was almost completely dominated by cisgender white women. Not only were transgender and BIPOC women denied the same platform and prominence, many of the white, cisgender musicians within the scene continued to remain loyal to trans-exclusionary radical feminist causes. For instance, artists like Kathleen Hanna of the Riot Grrrl band and zine both titled Bikini Kill performed at a festival called Michfest, which was marketed as only for “womyn born womyn.” Transmisogyny and racism existed in the Riot Grrrl community, but concurrent movements emerged that were more inclusive. Women of color during this time created something known as Sista Grrrl Riots, as a rejection of Riot Grrrl’s exclusivity. The Riot Grrrl movement fell mostly apart only a few years after its inception, and zine-making became more and more inclusive as it persisted into the twenty-first century. Though still far from perfect, there exists a robust zine community today, built on collaboration, collectivity, and support of each other’s art.

For a creator like Hasselmo, whose zines connect them to the present, zines are more than just historical artifacts. “I’m actually a really private person,” Hasselmo tells me. “But I somehow just feel the need to get my experiences down on paper.”

Despite being a self-proclaimed private person, Hasselmo finds joy and meaning in New Haven’s zine and comic arts community. Hasselmo was featured recently on February 26 at the New Haven Zine Fair at Bradley Street Bicycle Co-Op, organized by Connecticunt Magazine and Bridge and Tunnel Crowd. The Fair offered space for queer creators, like Hasselmo, to share their experiences through their art and engage with a community that is beginning to reflect a more multi-faceted queer experience that includes disabled creators, asexual creators, transgender creators, and creators of color.

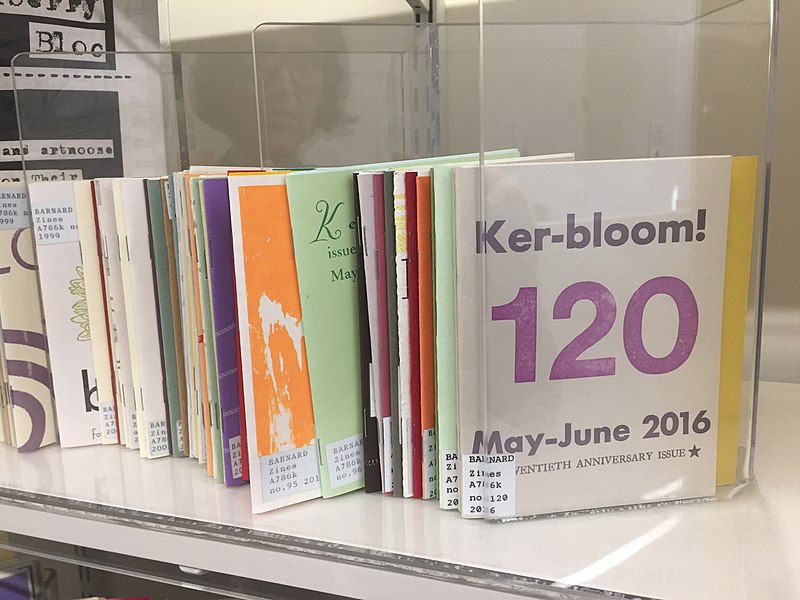

For as long as people have been creating them, zines have been a communal medium. As a zine creator myself, I have grown used to connecting on all levels with other creators, circulating my magazines by trading back and forth with other creators, giving a piece of myself in return for a small window into another worldview. Zines at Yale, though, are all the more complicated. Thousands of pieces of paper memorabilia are held in Yale’s Queer Zines, Magazines, and Newspapers Collection. The archive is vast and varied. I was touched by handwritten love notes on the backside of sepia stained photographs—declarations of queer vulnerability and longing are all the more painful when confined to vignettes. I was almost embarrassed reading Brat Attack, a 1993 black, white, and red comic newsletter that was full of visual and textual imagery, sparing no details about the experience of queer femme sex and bondage. The last zine I explored was the best: the words of Allison Wolfe of the femme punk band Bratmobile in the zine Girl Germs, examining what it means to be “punk” and writing, “We should really think about and talk about what punk means to us and who we really are and what kind of privilege (or lack of) we come from.”

Yet, as a zine creator myself, familiar with both the history and present face of zine culture, it was troubling to visit the archive room. Why were they even there? Zines have always been deeply intertwined with their creators and their zine communities, and in the folders of a Yale archival collection, even the most lively expressions of alternative, progressive culture are reduced to inert records. The troubled yet important history of collectivity that they represent is completely tucked away in the recesses of an institution which, for a lot of people, represents the same status quo that contributed to their exclusivity.

In 1989, the Yale Police Department arrested activist Bill Dobbs for hanging posters in Yale Law School to spread awareness of AIDS care groups in New Haven. Many artists and prominent figures of zine culture died of AIDS, largely due to the negligence and homophobia of powerful institutions. In fact, less than a year after Dobbs’ arrest, the artist Keith Haring died due to complications with AIDS. Now, just a few decades later, how we are supposed to accept that Haring’s work is sitting in a collection of archives owned by an institution that perpetuated queer violence durning his lifetime? Bikini Kill, probably the most lastingly popular zine of the Riot Grrrl movement sits closed, untouchable, behind a glass case as part of an exhibition called Points of Contact, Points of View. With or without the glass, as long as they are tucked away in little folders, we will never confront them as part of a living history.

On campus, as marginalized students carve spaces for themselves that prioritize inclusivity and accessibility, zines have found their place. I am drawn most to a zine on campus called DOWN Mag. Lighthearted listicles are an important aspect of their content, such as one example entitled “Nonhuman Characters That We All Know Are Black,” which includes Marceline the Vampire Queen from Adventure Time as well as all of the penguins from Happy Feet. But they also produce more serious pieces, such as their call to “Abolish Directed Studies,” on account of its serving as “a vehicle committing violent acts of intellectual privileging against marginalized groups at Yale.” I spoke with staff writer Anaiis Rios-Kasoga ’25 (she/her) about her experience writing for DOWN.

“DOWN is the only on-campus publication that only publishes things written by people of color and for people of color, so that is really cool,” says Rios-Kasoga. “Our main goal is just to highlight community and culture voices that don’t find an outlet at most other publications at Yale.”

Rios-Kasoga was drawn to DOWN for its grassroots nature—writing for the magazine didn’t feel like working for a distant institutional force, like journalism at Yale often has a tendency to feel. “[We] don’t have a classic editorial structure that most print magazines have. We are just a board of directors, there is no editor-in-chief—there is on paper, but it doesn’t operate like that.” Rios-Kasoga will serve as the arts and culture editor for DOWN next fall, and she hopes to continue using the platform to communicate her experiences as a woman of color, as DOWN continues to be a space for collectivity and communication for BIPOC students navigating Yale’s many tumults.

Zines are collectiveness distilled into its purest form. They are objects of communication, self-sustaining pieces of art, and personal declarations of one’s right to own and express their perspective. As both a creator and a consumer, I am moved by their power. After speaking with Hasselmo and immersing myself in New Haven’s zine culture—past and present—I am left certainly with more questions than answers, but also with the overwhelming desire to keep creating. Personal creativity, I am beginning to learn, has the power to open dialogues and doors that are long overdue to be unbarred.

—Madelyn Dawson is a first-year in Silliman College.