In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. (John 1:1)

Last year, I spent three hours every Wednesday afternoon being battered by the truth of Yale’s 7:1 student-to-faculty ratio—more teachers in a classroom is not always better. There were nine students enrolled in “Neighbors and Others” and three teachers: the wonderful Professor Levene and her two TAs, American Alison and British Ed.

It wasn’t supposed to be like this. There were originally twenty-six students. But on the first day of class a senior philosophy major, Andrew, asked Professor Levene what the thesis of the course was, and when she hesitated and told him to find out for himself, five people left the Zoom. Andrew stayed, but twelve other students dropped out over the next three hours as we discussed the Bible, and I don’t know why I didn’t follow them. I participated exactly once that day, at the very end of class, and nearly cried afterwards.

Am I my brother’s keeper? (Genesis 4:9)

Yale seminars are scary. Once, when we were asked about the audience of a book, the class was subjected to a Davenport senior’s slow, thought out answer, adding terms one by one as he came across them: “The audience for this book is likely liberal…. elite…. intelligentsia….” he said, pausing for a moment, “and probably coastal….” He is a legacy student and from New Jersey; it felt like watching someone masturbate. I recall, during a class on Glenn Gould, hearing the phrase “sonic sounds” leave someone’s lips (sonically). And once, while workshopping an essay in a different class, I remember every student in the classroom (myself included) complimenting the same awful metaphor about how, from above the lake’s surface, you can’t see how hard ducks paddle underwater. We each said what we liked about the essay and what we’d want to improve and then, when we ran out of things to say, added: “Oh, and I also liked your duck metaphor.” It was like baby ducks following baby ducks: a bunch of dumbasses paddling in a circle.

I wish so badly I could claim to be better than them, but I am not. I spent most of my first year too overwhelmed to participate in almost anything, and when I did speak I was only barely aware enough to register how dumb I sounded. No matter what was in my mind, everything seemed to come out the same way: “Nice ducks!”

We have different gifts, according to the grace given to each of us. If your gift is prophesying, then prophesy; if it is serving, then serve; if it is teaching, then teach. (Romans 12:6-7)

Talking to Professor Levene at her office hours, I learned that her purpose for the class was teaching us to read. She could easily lecture to us about the texts and tell us what we should know, but she wanted us to learn to fight and figure things out for ourselves. It was obvious from our conversation that she didn’t think we were doing a good job.

Writing my first essay, I met with both British Ed and American Alison. They are incredibly kind people. “Your thinking is like a firework!” British Ed told me. I do actually think he liked me. “But it means that sometimes you go too fast and get ahead of yourself, and don’t articulate your thoughts properly. Just work on those middle stages between the shell and the final explosion. I’m excited to see what you come up with.”

I met with American Alison to brainstorm and within ten minutes she told me I could drop the first essay if I needed to.

‘Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind and with all your strength.’ The second is this: ‘Love your neighbor as yourself.’ No other commandment is greater than these.” (Mark 12:30-31)

At the end of the semester I stopped doing the readings for “Neighbors and Others.” In the beginning, when I had done the reading and had a lot to say, British Ed really liked me and I sat next to him most days. By the end of the year I was quiet, and sometimes I could feel his eyes on me, imploring. I’m not sure whether I imagined those questions in his gaze, urging me to speak! and learn! and practice thinking! and struggle please because it’s okay you’re safe here! But I stopped looking in his direction so I can’t say what really was in his eyes. I felt bad imagining he wanted what was best for me.

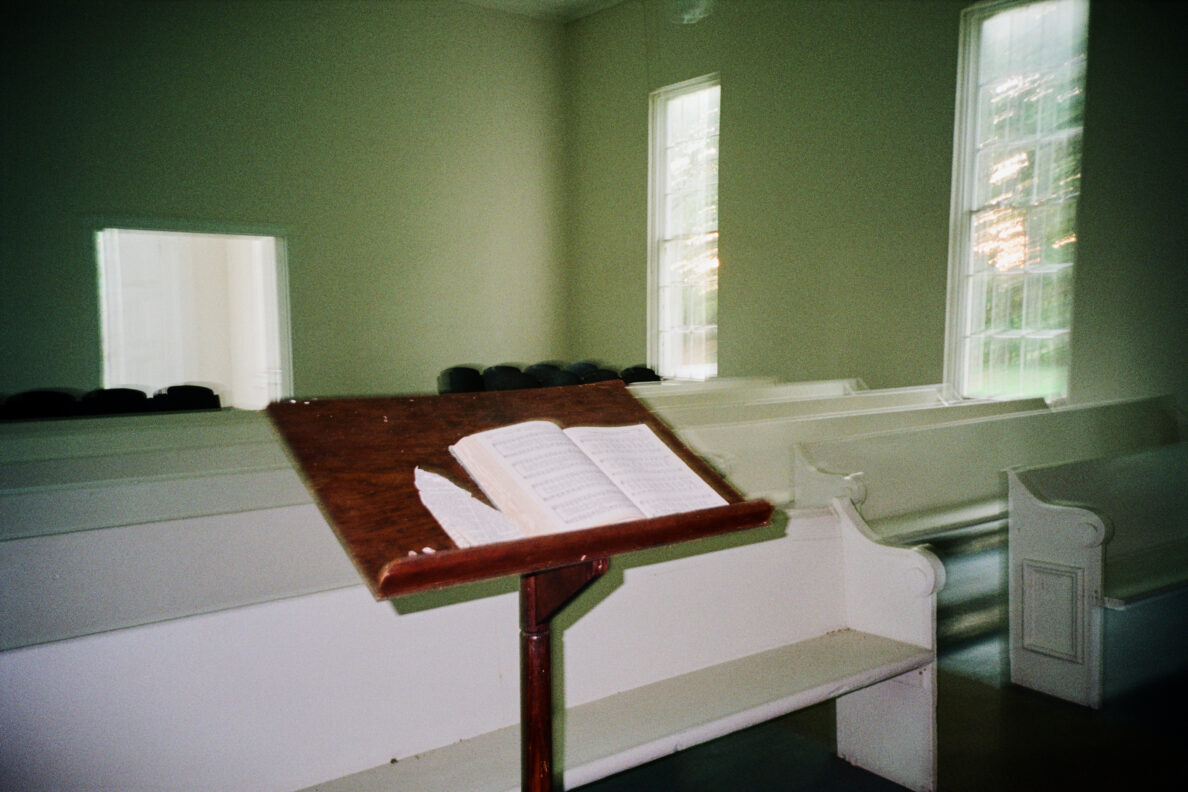

On the last day of the year we talked about all the texts we had read and each of us brought our favorite quotes to class and wrote them up on the board. One student skipped. But the discussion that day was beautiful and I could almost sense Professor Levene’s purpose for us, a purpose we had missed all semester, some path towards dissolving the divide between “Neighbor” and “Other.” But I still didn’t quite get it. I had trouble understanding a lot of the quotes. Everything from Spinoza, Winicott, and de Castro confused me without its context, and the only sections I really understood were from the Bible and the first day of class. Love your neighbor. Give to the poor. Take responsibility and be good.

In a moment of silence just before the end of class, I spoke and addressed Andrew, reminding him of the task he’d been set at the beginning of the year—to discover the class’s thesis himself.

“So what would you say now?” I asked, and people laughed. I really respect Andrew. This was his second to last day of Yale, and I was curious about what he had gotten from it all, when I felt like I understood so little.

“Oh!” he said. “I remember that. But I don’t think I could do a better job than what we all brought here today. The quotes.” We all looked up at the board and read the quotes and were silent. Confronted with so many words and so many ideas from so many authors all at the same time, the letters spun together and I couldn’t understand anything at all.

But alright, Andrew. Have it your way. The thesis is in the quotes. The meaning is in the quotes. You apparently have learned to read. I did not.

— Shane Zhang is a sophomore in Silliman College.