One of the best tattoos Sam Jannetty has recently made was for a fellow lesbian. It was two black-and-white scissors, well, scissoring. Like she does with all her designs, Sam posted this tattoo to her Instagram page, sprinkling rainbow emojis in the caption: “IYKYK.” (If you know, you know.)

Sam is the owner of Broken Crystal Tattoo Studio in Milford, Connecticut, which she advertises as a queer-friendly tattoo shop. The descriptor is unnecessary. “I mean, we’ve got frickin’ Rick and Morty playing in here,” Sam says, gesturing to a large flat-screen TV hanging on a robin-egg blue wall. The rest of the shop resembles an explosion of a Pride parade. There are rainbows everywhere: a rainbow fan, splayed open next to a poster with a chicken nugget on it that reads “NUGS, NOT DRUGS”; a rainbow tapestry depicting UFOs abducting people from Earth; and rainbow Pokemon figurines filling a plastic bowl on the coffee table as if they were front desk mints. On my first visit, I had no trouble finding the shop in an otherwise nondescript suburban strip mall, as Sam had also hung a set of sheer rainbow curtains on the front window. Sunlight streamed through, casting kaleidoscopic reflections on the tiled floor.

It’s in this rainbow-tinted sunlight that I watch Sam show me her own tattoos. “I think I have, like, thirty-five?” She pauses, squinting in the brightness as she counts. “Yeah, I’d say thirty-five tattoos.” With her colorful arm tattoos and neon hair that she dyes and re-dyes on a whim, Sam settles in her store perfectly. “I wouldn’t worry about putting that too close to me,” she says, making a slight shooing motion when I adjust my phone to record our conversation. “I’m loud as hell.”

Sam doesn’t quite have sleeves—or at least not yet, she tells me—but her tattoos nearly envelop her forearms. She raises her arms, wrists turned upward, to give me a better look. There’s a red Pac-Man, a matching tattoo she shares with her siblings, next to a large moth that wraps its wings protectively over her right elbow. She also has an ice cream cone with a skull on top of it, a happy little alien holding on to a happy little cat, and a tiny fish tank (because she has a tiny tank—a small bladder—herself). Many of her tattoos were drawn by other artists whom she lets practice on her own skin. There’s no coherent theme tying all of these designs together, but I’m surprised to hear that she thinks a lot of these permanent creations suck. “This one here,” Sam says, pointing to a very gay, very rainbow gradient bar on her upper arm, “when the artist started, and I saw the ink bleeding together, I thought, ‘Oh, shit.’” She shrugs and laughs.

Sam runs Broken Crystal (she chose the name because it’s rather “pastel goth,” she says) with her sister Chloe and another colleague. The shop opened in April 2021 and has drawn a loyal, mostly queer cohort of tattoo enthusiasts. Sam started tattooing around her college graduation, five years ago. In that time, she’s seen her fair share of the less savory side of the tattooing industry. She got her tattooing license by enrolling in a tattooing school, ignoring the traditional route of becoming an apprentice to a more established artist. But Sam found the school, with its exorbitant tuition and a general lack of committed instructors, to be highly exploitative. Sam primarily taught herself by practicing, for hours upon hours, on fake skin and fruit rinds, and eventually joined a tattoo shop in New Haven as a new artist. But the shop she worked at was a far cry from the one she owns now. Most of the other artists were men, who would occasionally hit on their women clients. Sam, a “hundred-footer” (someone you could spot as gay from a hundred feet away), immediately felt out of place. “I was the show pony of the shop,” she says.

Sam hates being told what to do, and her anti-authoritarian impulses blossomed as she grew tired of traditional, male-dominated tattoo shops and their hypermasculine decor. After saving up some money, she left the old shop and opened her own studio. “They’re all the same,” Sam says. “You walk in, and there’s a motorcycle up front. There’s some creepy-ass version of metal music in the background, all these guys around. It’s like a sit down, shut up, get tattooed kind of thing.”

At her old shop, Sam had to endure some rather bizarre tattoo requests. Once, a gay man walked in and demanded that she tattoo the f-slur on the inside of his lip. He wanted to reclaim the word, and a queer artist should help him do it at the very least, right? Another time, a couple—it’s always the couple tattoos—wanted each other’s names tattooed on them in a brushstroke heart with three money wads on one side, three pot leaves on the other. No matter what, Sam reserves most of her judgment, with the exception of turning down one customer who insisted on getting a butterfly tramp stamp that started in her ass crack.

“Sometimes I’m like, you really want to get this shit on you right now?” she says. She lets out a brief sigh. “But if you want it, you want it. Go for it.”

***

I decided to get my first tattoo a couple summers ago, when I began dating women for the first time. It was a simple line drawing of two koi fish swimming around each other, designed by my childhood best friend, who is also queer and Chinese. I knew I wanted it on my arm, or somewhere visible on my body. I wasn’t going to hide it under a sleeve, or keep it tucked behind my ear. My body and I have had a strained relationship, and it became even more tense during lockdown. I had little to do besides waste time in my childhood bedroom, watching my body and face mutate and metamorphose: gaining weight, losing weight, gaining it back, plus more; cutting my bangs, dying my hair. I became less interested in looking thin, pretty, and appealing to men—the things I’d been concerned about before the pandemic cut my sophomore year of college short—and more concerned with just looking different. Having a visible tattoo was a part of that journey.

Sometimes, I look through the CVS photos that used to hang under the string lights in my dorm. The photos remind me of how little I recognize in my old self. In one photo, she’s wearing a hot pink dress, her arms draped around a friend. She’s drunk, but laughing. In another, her long hair spills over her shoulder as she leans over to kiss a boy on the cheek. The person in the photos was twenty pounds lighter, more delicate, more feminine, and very, very straight.

No one else in my family has a tattoo. When I was mulling over my first tattoo, my mother lamented to me that no one would hire me if I got one. I had to reassure her that the only occupations I could foresee banning tattoos were preschool teachers and the Navy, and I had no intention of joining either. But I could understand her ambivalence. In the weeks ahead of my appointment, questions swarmed in my mind. What if I don’t like the way it looks on my body? What will happen when I’m older, when my skin sags and swells, when the ink blurs and fades? I shuddered to imagine the wrinkles forming around those two fish, their bellies slowly bulging and bloating along with my own.

Getting a tattoo is a dull, monotonous pain, like getting stung by a microscopic bee over and over again—only, the bee is actually a thin needle puncturing your skin up to three thousand times per minute. When the needle punctures your dermis, the second layer of your skin, and injects a spout of ink, your body sends white blood cells to attack the foreign particles. But tattoo particles are larger than the particles white blood cells can dispose of, so the ink remains. A tattoo is a wound you wear forever. I thought of this as the artist moved the needle to the thickest, most fleshy part of my shoulder, as I closed my eyes and felt the machine buzz into my skin.

***

Although Sam’s workspace in Broken Crystal, like the rest of the store, is a shock of colors and trinkets, it serves a utilitarian purpose too. On a simple black shelf, miniature figurines of monkeys, unicorns, and skeletons stand with the order and obedience of a newly conscripted army among sterilized needles, gauze pads, and Vaseline. Among their ranks is a dried out orange peel, preserved proudly in a glass case. There are faint black scratches shaped like fish and flowers on its side, likely some of Sam’s earliest etchings.

In her sanitized, well-organized nook, Sam is showing a custom design that she drew on her iPad to Tatiana, her client today. Tatiana, like most clients, found Broken Crystal by asking around for good queer tattoo artists in the area. The design is rather bare bones, without the shading and detail that Sam will include later. Flowers are one of Sam’s specialties; she can usually draw them from memory.

After Tatiana approves the design, Sam prints out a stencil version on carbon-based paper in washable ink. The stencil is what’s used to determine the tattoo’s placement, and what the artist ultimately traces over during the actual tattooing. Sam shaves Tatiana’s calf and disinfects it, and reaches past her collection of Dr. Seuss-themed bobbleheads for a thick, purple gooey substance. She applies the goo generously to the stencil on Tatiana’s leg. When she peels it away, we see the final design: a delicate sunflower, its stem a trail of cursive spelling out the name of Tatiana’s late aunt. Sam has watched clients decide on one placement, then decide it was too high, then too low, then too off-center, before concluding that their original placement was ideal all along. But Sam is always patient. “I want people to feel comfortable with whatever goes on their bodies,” Sam insists. Thankfully, Tatiana likes the initial placement too.

Watching Sam work, I learn that tattooing is a lot like painting, and Sam, a lifelong artist who attended an arts high school, is a practiced impressionist.

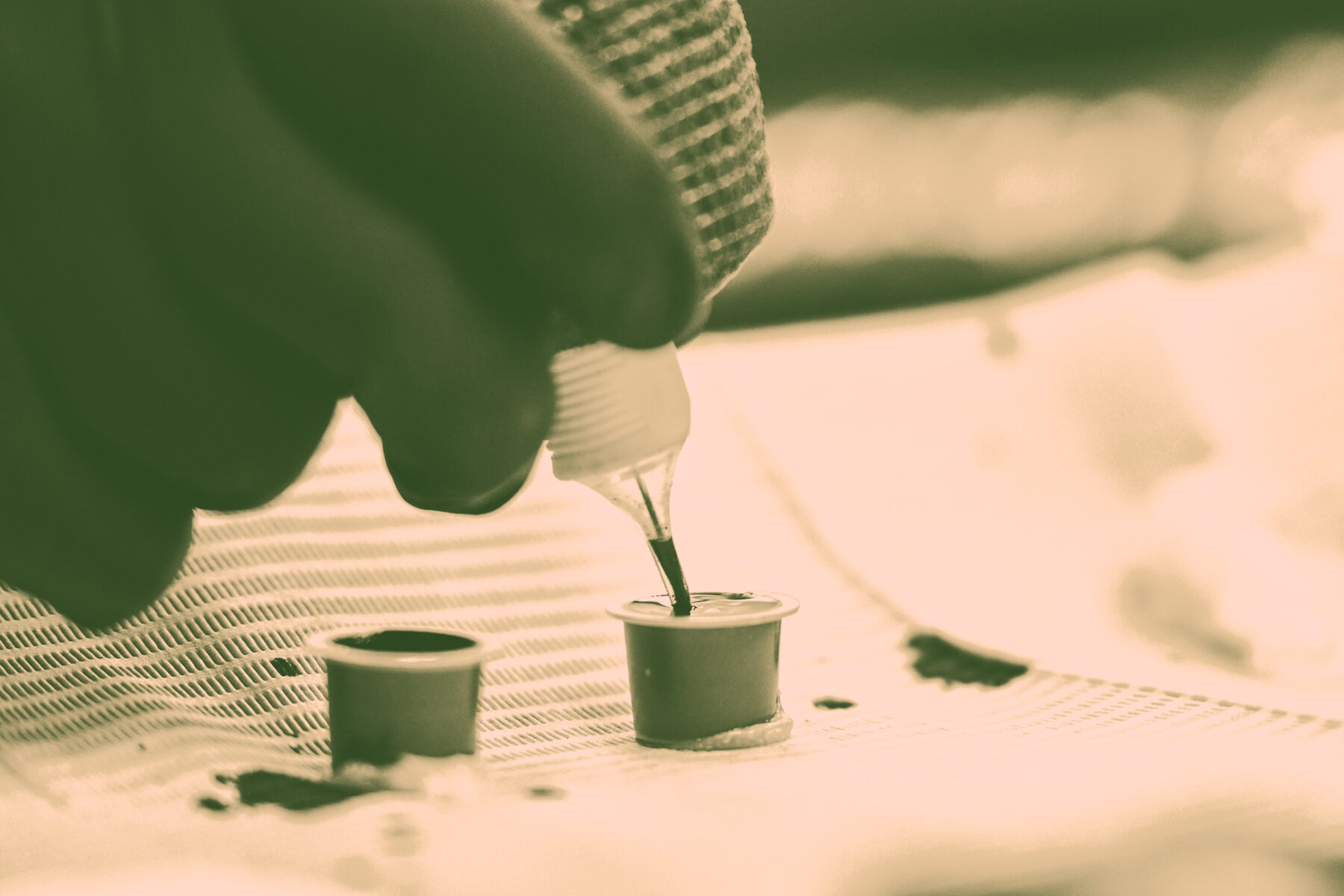

Watching Sam work, I learn that tattooing is a lot like painting, and Sam, a lifelong artist who attended an arts high school, is a practiced impressionist. She first makes a gentle outline of the sunflower on Tatiana’s leg, carefully and slowly tracing out the hair-thin stem, each folded petal. She uses a handheld needle—not one of the heavy, traditional needles connected to a power outlet that shakes when you turn the voltage higher—because it feels like using a light paintbrush. Once the black outline is down, she goes in with the colors, starting with the lightest shade and moving to the darkest, easing them into the skin like slow, weighty watercolors.

Sam tells me, much to my surprise, that she suffers from carpal tunnel syndrome. Her hand tenses up sometimes, which can make tattooing rather uncomfortable. When she tattoos, her vivacious, effervescent expressions grow more subdued. She quietly and steadily holds the tattoo gun in place, applying brief dabs of Vaseline to make sure the ink enters the skin seamlessly. She checks in regularly with her clients—“You hanging in there? Does that hurt?”—before returning to her work with intense focus. She tells me that she hates seeing her clients in pain. “I hate hurting people,” she admits, “even though that’s my job.”

Sam remembers the pain of her first tattoo too vividly. She had just turned 18, and her parents had finally let her get that ambitious tattoo she had wanted for a long time: a giant, multicolored dream catcher that encircled her back, inspired by Disney’s Pocahontas. “You know, ‘Colors of the Wind’ and blue corn moon and all of that stuff?” she reminisces.

The full color tattoo took around three hours to complete. It felt like a hot knife going into her back the entire time. The male artist was a family friend. “Everything about it was awful. There was metal music playing, skulls everywhere, and the guy’s got a big bike outside, bulldogs in front,” Sam groans. “He’s got greased-back hair, tattoos everywhere, like the most cliché tattoo shop you could possibly go to. And of all the names, the shop was called, like, COMMITMENT.” She spits out the word dramatically.

“Why did you choose to get more tattoos?” I ask. “Thirty-four more, to be exact?”

“It’s like having a kid,” she says nonchalantly. “No one likes being pregnant. No one likes [childbirth], but you like [kids] when they’re 18 and out of your house. And then they’re here to save you later.”

***

The word “tattoo” comes from the Tahitian word “ta-tu,” meaning to write or mark, which is what Indigenous communities in the Pacific Islands had been doing for generations before European colonization. For Indigenous peoples, tattoos served more than an aesthetic purpose. They were protective talismans, or even permanent, corporeal genealogies, each one marking an individual’s social status and lineage. Eighteenth-century Europeans, however, found these exquisite markings of animals, patterns, and nature to be primitive—albeit fascinating—oddities. Colonizers captured tattooed men and women to display at world’s fairs, placing them in “human zoos” where other Europeans could gawk at the savagery of the lesser known, un-Christian parts of the world. Sandwiched between exhibits boasting the latest models of steam engines, or other novel tools of industrialization, these human zoos completed stadial theories of evolution. The tattoo was understood as a feature of the “uncivilized Other,” whose body was made purely for public consumption, asserting the superiority of the Western world.

The public perception of tattooing in the West changed with the invention of the tattoo machine, which made tattooing less time-consuming and more accessible. Around the same time, Western powers set up formal military outposts in the Pacific, placing male soldiers in Asia. Many returned home with dragons, geishas, military insignia, flags, or even “MOM,” or a fiancé’s name written in an obnoxiously red heart. The practice grew in popularity and spread among veterans, working class men, the Chicano movement, biker gangs, and queer subcultures. Suddenly, tattoos had new, subversive meanings: they were marks of survival, resilience, pride, and resistance against a world that marked you as Other.

When I first discovered the queer tattooing scene, I was surprised by the number of queer artists, especially artists of color, who were committed to unsettling tattooing stereotypes. Like Sam, they weren’t interested in abiding by overly masculine, Orientalist, or conspicuously white and Western tattoo traditions. Their designs were thin and detailed, inspired by Gothic design, traditional Korean and Chinese artwork, queer subcultures—anything counter-hegemonic. They wore their tattoos proudly. When I turned 21 and started visiting queer bars and clubs in New York City, I noticed, alongside mullets and ripped tops, arms and legs covered in monochromatic and colorful designs.

At the same time, I began delving into feminist and queer theory, taking in ideas that celebrated body modification as a subversive act. I began to understand my body as a site for my politics, and a site where difference is made apparent and celebrated. Perhaps this is what I wanted when I got my first tattoo, then another, and another: to destroy and incinerate my straight body, to coax out a new visibly and conspicuously queer body—the one I had hidden for so long by growing out my hair, painting my nails, throwing up, starving myself, wearing bodycon dresses, and sleeping with men. I, too, hoped that tattoos would save me. As I walked out of the studio last August and passed my hand over the fresh wound of my new tattoo, I traced the two fishes, wanting to feel like a phoenix breathing in its first breath of air.

Perhaps this is what I wanted when I got my first tattoo, then another, and another: to destroy and incinerate my straight body, to coax out a new visibly and conspicuously queer body—the one I had hidden for so long by growing out my hair, painting my nails, throwing up, starving myself, wearing bodycon dresses, and sleeping with men.

***

In her senior year of college, Sam realized she was developing feelings for her roommate. It was something she had never really experienced before. “Great times, like Stockholm syndrome,” she concedes, rolling her eyes. “I just liked them because I was around them so goddamn much.” She finally decided it was time to come out, though she had known for a long time that she wasn’t attracted to men. In high school, she avoided dating anyone. While her friends talked about their school crushes, she shuddered at the thought of kissing a boy.

I empathize with many moments in Sam’s coming out journey. There was the ambivalence toward most men who hit on her, the general lack of interest in presenting as overly feminine, and the one very intense female “friendship” in high school that had turned out to be a blatantly obvious crush, followed by a similarly intense friendship breakup. “I mean, I showed up to this girl’s doorstep on Valentine’s Day with frickin’ flowers and a teddy bear,” Sam says, cringing.

Sam passed as a straight woman for most of her life. She grew up in a community and went to a university where she was one of few queer women. She wore her hair long, donned shapeless, unremarkable clothes, and tried to look the least Sam as possible. She was even voted prom queen, an irony she acknowledges with a chuckle. It wasn’t until she opened Broken Crystal that she started to meet and make queer friends. She started presenting as a hundred-footer, with collared shirts, a whiff of short hair, and arms full of tattoos. She started dating a woman—Sara, her girlfriend of over four years—and buzzed away her hair.

When I ask her if she noticed people treating her differently after she came out, she tells me about an encounter she had with a Christian proselytizer when she worked at Walmart a few years ago. The proselytizer had noticed Sam’s colorful half-sleeves and remarked that tattoos are not “what God wants.” Enraged, Sam told the woman that she had a pair of demon wings inked on her back—and she was going to tattoo her face next.

“I’m going to Hell for a lot worse than my tattoos,” Sam laughs. “I’m gonna go down for being frickin’ gay.”

***

On one of my visits to Sam, I noticed that she has a tattoo of two overlapping cards on her left arm. The first card read: “THIS TATTOO IS PERMANENT.” The second, “THIS BODY IS TEMPORARY.”

“What does that mean?” I asked.

“This? Oh, I just thought it was funny,” she started, then paused for a moment. “But my whole thing is: if you want it, you want it. If you want a tattoo just because it looks cool, go for it. It’s a memory. Obviously there are some stupid tattoos, but people do stupid things every day. I mean, I’m driving a Jeep every day.” She gestured wildly to said vehicle in the parking lot. “Them shits flip.”

“People are obsessed with making their tattoos perfect because it stays on your body forever, and then I have to explain to them that their bodies are not perfect to begin with. But that’s okay—it’s good to have your tattoos a little bit crooked, because our bodies are a little bit crooked. There’s something comforting to me about that permanence.”

***

For my last visit to Broken Crystal, I decide that I want a new tattoo. I don’t think much about it as I wait in front of the studio on a bright, crisp November morning. I’m just feeling a cool flower at the moment, or something of the sort. My mind jumps to the flower that shares a name with the first woman I dated.

Sam pulls up in her olive green Jeep. She steps out of the car with Sara, her girlfriend, whom Sam wants me to meet.

The three of us spend the morning chatting in the shop as Sam tattoos me. Sam first cleans the sensitive inside part of my forearm, placed on an armrest, with her usual tenderness and care, and the light from the curtains casts flashes of color on our skin. As the needle hits my skin, Sam and Sara talk about some of their nightmarish roommates—including a woman who let her giant pet rabbits shit all over their house—and it almost makes me forget about the dull pain in my arm. It feels nice to not be in reporter mode, to just listen and laugh.

“I think that’s done,” Sam finally says. She dabs Vaseline, wipes it gently with a paper towel to reveal the finished piece. “Do you like it?”

I look down at the detailed, refined stem, the petals curling so realistically—as if scorched, briefly, by sunlight. I do.

Eileen Huang is a senior in Timothy Dwight College.