Beginnings

On the night of August 17th, 2022, Dr. Christy Olezeski received a Twitter notification. Then another, and another. She was on vacation with her family, taking a break from New Haven and the pressures of her work as Director of the Yale Pediatric Gender Program (YPGP). She hadn’t even brought her work laptop with her—her goal was to unplug. But, as the Twitter notifications streamed in, she realized something was wrong. The world had found her.

Dr. Olezeski, as she is affectionately known by her patients, knew it was only a matter of time. Right-wing activists had launched threats targeting Boston Children’s Hospital earlier that same month, and the year’s legislative sessions had seen a slate of anti-trans bills passed in Texas, Alabama, and Idaho. Dr. Olezeski hadn’t been deterred—but when she saw that Libs of TikTok, a right-wing Twitter account with over a million followers, had reposted a video of her from the YPGP’s website, she knew the YPGP was in danger.

“I give it 24 hours before I get my first death threat,” she thought to herself. The next morning, Dr. Olezeski woke up to four emails she described as “quite unpleasant.” Within two days, the story was picked up by international conservative media outlets including Fox News, the New York Post, and the Daily Mail. “Yale professor blasted for program working with 3-year-olds on their ‘gender journey,’’” read Fox News’s headline. More emails streamed in, and phone calls and letters began arriving at the clinic. Some of Dr. Olezeski’s harassers even found her home address, sending letters directly to her house. Dr. Olezeski was the face of the YPGP, and so far-right media outlets and influencers like Libs of TikTok descended on her as an emblem of “gender ideology,” a term used in transphobic politics which presents the existence of trans people as a threat to society. In total, she and the clinic received hundreds of threats.

As Dr. Olezeski sat in one of the clinic’s sterile conference rooms, recounting the harassment on a cloudy afternoon last February, she took a deep breath. Then she took another, and then another. And, finally, she began to cry. Dr. Anisha Patel, one of the co-founders of the YPGP alongside Dr. Olezeski, hugged her. “We’re huggers here at the clinic,” Dr. Patel affirmed. Dr. Patel sat back down, but Dr. Olezeski began to cry again, so Dr. Patel returned for another hug and continued to sit by Christy’s side. The two took a moment to collect themselves, and then Dr. Patel emphasized that, after the threats, “the support came from the team. We were always pretty close, but now we’re like a little family.”

The Yale Pediatric Gender Program started with an email. In 2014, Dr. Olezeski was working in the Department of Psychiatry at the Yale School of Medicine (YSM). After speaking with trans community leaders in New Haven about the needs of the trans kids they worked with, Dr. Olezeski emailed the Department of Endocrinology to ask who was providing healthcare to trans youth. The response was concerning: Yale had no such program. Luckily, there were other interested doctors in the pediatric endocrinology department at YSM, including Dr. Patel.

Prior to 2014, Dr. Patel had the occasional trans patient but lacked the infrastructure to do anything but refer them to hospitals in Boston and Hartford. One patient of hers lacked the resources to make it to either city. “I don’t have anywhere to go,” the patient told her. “You’re my doctor, and I want you to do this for me.” Dr. Patel looked him in the face and made a promise: “I will figure this out.”

With the addition of Dr. Susan Boulware and Dr. Stuart Weinzimer, both pediatric endocrinologists at Yale, the Pediatric Gender Program team officially numbered four. But before they could open their doors, they had to research. The team contacted academic pediatric gender centers across the country, discussing policies and procedures. The four doctors met monthly for a year to assemble their team. They recruited endocrinologists, psychologists, psychiatrists, an OB/GYN, an ethicist, and a lawyer. Every team member worked on a volunteer basis.

“We knew it was going to take a long time to go through the regular channels at Yale,” Dr. Olezeski said. But trans kids were in desperate need of care, and they had nowhere to go in New Haven. The team decided on a work-around: one half-day a month, the three endocrinologists would take on gender patients instead of their general endocrine schedule. The clinic officially started taking patients in October 2015. “There was no ribbon cutting,” Dr. Christy laughed. “It was all word of mouth in the beginning.”

But word of mouth traveled fast: wait times had ballooned to eight months by 2017. Soon after, wait times were measured in years. The team petitioned Yale New Haven Hospital (YNHH) for support, and, in 2018, were able to begin providing gender-affirming care for one full day per week. During the pandemic, they added clinics on the first and fifth Thursdays each month, growing to their current total of nine to eleven clinics per month. As of 2023, they provide services in New Haven, Trumbull, and Old Saybrook. To date, the YPGP has provided care to 425 people. But as more states across the country have adopted hostile attitudes toward trans teens, demand for the clinic’s services have grown, with patients streaming in from places as far away as Florida.

For many trans kids in New Haven and across Connecticut, access to care remains locked behind a waitlist and a multitude of structural barriers.

2020 was a difficult year for LGBTQ+ youth. 2021 was worse, and 2022 was no better. As of March 10th, 2023, bills have been introduced in 22 different state legislatures to criminalize gender-affirming healthcare. Recently, both Tennessee and Mississippi passed bans on gender-affirming healthcare for minors, and several other states, including Texas, appear poised to be next. While Connecticut has reaffirmed its commitment to the legality of gender-affirming healthcare, Dr. Olezeski still worries. “Connecticut is lucky to be in a place where there aren’t attacks actively happening, but it seems like the climate is still dangerous,” Dr. Olezeski said.

But the harassment Dr. Olezeski and the YPGP faced last summer has only strengthened their commitment to the trans community. “We’re not stopping and we’re just going to continue to grow,” Dr. Olezeski emphasized. “It’s made our team stronger, I think. And so we’re not backing down.”

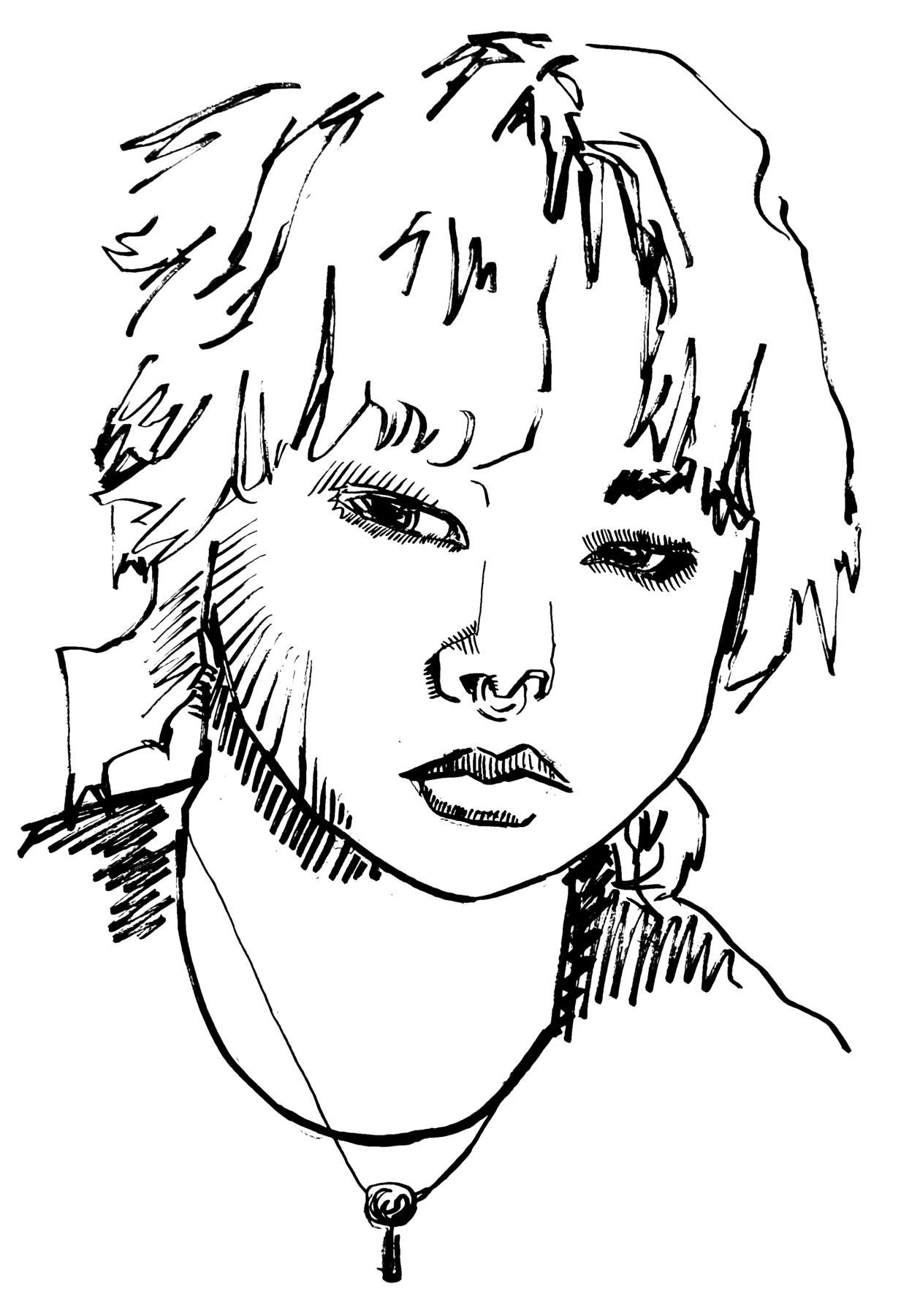

Rowan

On the eleventh of every month, Rowan gets a calendar notification: “record voice update video.” With his catalog of monthly videos, he can look back and trace the changes in his voice, an effect of the testosterone he’s been taking for the last year. “As someone who does a lot of singing, I started as a mezzo-soprano and now I’m a bass baritone,” Rowan explained. “That’s super, super cool.”

Rowan is fifteen years old, from a town north of New Haven. He loves Deftones, plays the guitar, and is excited about his upcoming role in the school musical. He’s also a patient at the YPGP.

When Rowan was thirteen, he told his parents he wanted to start testosterone. His voice dysphoria was so bad that he struggled to talk and didn’t want to leave the house. He had been questioning his gender since he was eleven, and he was finally sure that he wanted to pursue gender-affirming care. “I felt very guilty that I was kind of breaking their expectations of me,” Rowan remembered. Despite his anxiety, his parents were accepting from the beginning, and they were eager to meet his needs. They knew his quality of life was at risk.

In late 2020, Rowan and his parents got to work finding a clinic. Rowan’s parents called the YPGP, and they were lucky: when they called, the waitlist for an appointment was only three to five months. When the day of the appointment came, Rowan and his parents loaded up the car and drove for an hour to get to New Haven. He remembered being a little nervous but “very excited to see where it was gonna lead me.”

The YPGP was an instantly comforting space for Rowan. “It felt like they’re kind of a family,” he said. Even though it was a doctor’s appointment, it felt like a casual conversation where he could express his needs. After Rowan explained what he needed out of the clinic, they explained the options they had available for him. Rowan left his intake appointment with a prescription and a new outlook on life. “My confidence skyrocketed.”

Now, one year later, Rowan returns to the clinic every few months for follow-up appointments. First he meets with Dr. Boulware, then Dr. Olezeski and Dr. Patel. Rowan also meets with clinical psychology Ph.D. student Wisteria Deng to have a one-on-one conversation about his mental health and wellness.

In 2022, Rowan found out about a unique opportunity from the clinic’s mailing list: a circus workshop for trans kids. Rowan participated for a few months that summer. “It was a really fun experience,” he said. The workshop was a space to learn skills ranging from juggling to walking balance beams, and doctors participated right alongside the kids. Even Dr. Olezeski picked up a new favorite party trick: she can now balance a peacock feather on her hand.

At the Yale Pediatric Gender Clinic, Rowan has found more than just medical care: he’s found community. The YPGP changed Rowan’s life, and he knows it. “I’m very grateful that I have this privilege,” he acknowledged. Rowan’s case, however, is frustratingly rare. For many trans kids in New Haven and across Connecticut, access to care remains locked behind a waitlist and a multitude of structural barriers.

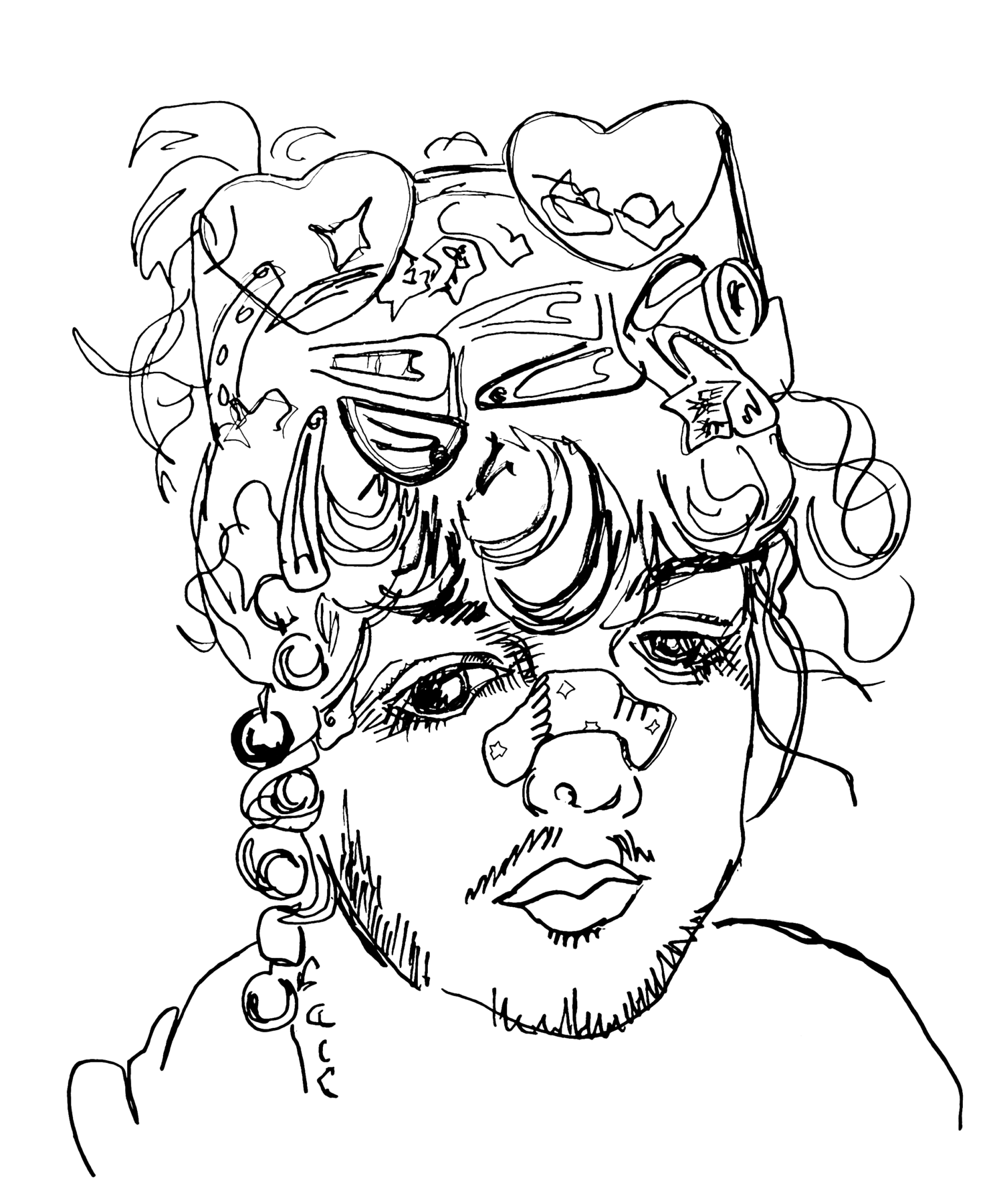

Jude

Jude Arnott was referred to the YPGP in 2019 after he was hospitalized at the Yale New Haven Psychiatric Hospital. Jude, fifteen years old at the time, struggled with overwhelming emotions and didn’t know how to cope. He struggled with outbursts, aggression, and suicidal ideation. He would later realize that many of his struggles were the result of gender dysphoria, dysphoria he had struggled with for years. When he found himself back at YNHH in 2019, the doctors on-call recommended he make an appointment with Dr. Olezeski at the YPGP. So he tried. And tried. And tried.

When Jude told his parents in 2015 that he wanted to start to socially transition, his parents didn’t bat an eye. “They were incredibly supportive,” said Jude. “I am one of the luckiest people… My parents have health insurance, they were supportive, and I was in a place where I could get gender-affirming healthcare.” But as Dr. Olezeski stressed, for every person like Jude, there is at least one teen who wants to transition, but doesn’t have parental support or the financial resources to do so. “I worry about those kids,” said Dr. Olezeski.

Jude was placed on the YPGP waiting list. The YPGP told him and Kathleen, his mother, that it would be at least three years until he could be seen for an intake appointment. But Jude was in need of immediate attention: he was in and out of the hospital, and his relationship with his brother and parents was under strain, punctuated by fights despite their support. He required treatment immediately, but the YPGP simply didn’t have the capacity. Jude and his parents had to look around for the next best option. Wait times at the YPGP can vary widely from year to year. “There’s also increasing demand, though our clinical contribution has increased, we just can’t keep up,” Dr. Christy said.

While Jude’s decision to leave the YPGP’s waiting list was quick, the process of finding other care was difficult. At first, Jude saw a gender therapist in the New Haven area. After six months, he received a letter of written support from his therapist attesting to his need for treatment—these letters are a necessary first step toward beginning gender-affirming treatment at many clinics. He also obtained a referral to the Connecticut Children’s Medical Center’s Gender Identity Program (CCMC). Letter in hand, he and his family called CCMC to schedule an appointment. The process was quick: after his first visit at CCMC, Jude was prescribed puberty-blocking medication. A doctor placed an implant in his arm, and shortly thereafter he began hormone replacement therapy.

Jude also attempted to get “top surgery,” a masculinizing bilateral mastectomy, from a surgeon at Yale New Haven Hospital. According to Kathleen, the surgeon’s staff refused to update Jude’s legal name in their system, which she says led to them deadnaming Jude—referring to him by the name on his birth certificate that he no longer identifies with—over twenty times. Kathleen struggled with Anthem, her insurance provider, whose coverage of gender-affirming surgeries does not typically extend to minors. And then, after a year and a half of waiting, she received a call: the surgeon had retired, and the surgery was canceled. The surgeon’s office didn’t return a request for comment. At the age of 15, and long after the ordeal at Yale, Jude was finally able to receive top surgery at CCMC. “It was tough for him, but if there’s one thing about Jude, if he wants to do something, he’s going to do it,” said Kathleen.

Families’ relationships with the YPGP differ. While Rowan was lucky enough to avoid the YPGP’s growing waitlist, Jude was never able to schedule an appointment despite an inpatient psychiatric referral. Oftentimes, a family’s experience with the YPGP is driven by factors outside their control. Insurance policies, distance between the clinic and a family’s home, and the support (or lack of support) parents show for their child all influence a family’s ability to find treatment. But for trans teens, time is ticking. With every passing minute, they’re going through puberty—the wrong puberty—and undergoing the unwanted, irreversible physical changes this puberty brings on.

Alex

Alex, an eleven-year-old in New Haven, could be described as a free spirit. She refuses to conform to society’s expectations of what a boy or girl should be. She likes to experiment: with her uniform at Elm City Montessori, her name, her pronouns. She’s obsessed with Disney’s Frozen: according to her mother, Jessica, the movie was a formative part of Alex’s gender journey. Jessica and her wife didn’t think much of it at the time. “We were like, Alex is a kid who loves long hair, loves princesses, and loves powers. That kind of thing.”

“…maybe they’re providing great services, but if my kid can’t get them, that makes me mad.”

As Alex grew, she felt limited by her peers’ expectations of her. She didn’t want to be a boy. She didn’t want to be a girl. But after talking with her parents, she decided that, if she had to be one or the other, “I choose girl,” she said. For Jessica, “the pressures are still there to call certain behaviors girl behaviors and others boy behaviors.” Even though, as Jessica was quick to point out, East Rock and New Haven are very welcoming places to be trans, there are still biases and uncomfortable situations that Alex has encountered. For example, at school, there were only boys or girls uniforms for her to pick from. This is something that Jessica admits Alex will have to live with, but “so far, she’s doing a great job.”

In late 2021, at the urging of their pediatrician, Alex’s parents decided to schedule an intake appointment with the YPGP, they were informed that the wait time was 13 months. But Alex had time. She hadn’t started puberty, and while the wait was long, it was something they were willing to put up with. The quality of care at the YPGP made the wait worth it, Jessica had heard. So as long as Alex was fine with the wait, there was nothing to lose—until they received another call from the YPGP. Alex’s appointment had been canceled, and they would have to reschedule for another 13 months later. That was enough for Jessica. “There’s this feeling that maybe they’re providing great services, but if my kid can’t get them, that makes me mad.”

To meet the demand of their current waitlist, the YPGP needs to add more clinic time and hire more doctors. With appointments that average 90 minutes, they need more time than most endocrinology providers. However, the YSM administration has been pushing back on their requests for more resources. “When there’s limited space, they’re gonna say, ‘No, we don’t want you to open another gender clinic, we want you to open up a general endocrine clinic, because short kids need to be seen too,’” Dr. Boulware said, referring to cisgender kids who need support for atypical puberty. But there are dozens of endocrinologists treating cisgender kids in the New Haven area, while the YPGP is the only program serving trans kids.

As a stopgap measure to help those on the waitlist, the YPGP provides events and community to any trans kid in the area. Dr. Olezeski first started a parent support group and then expanded to a youth group. She offers the events to anyone on her mailing list as a way to provide outlets for trans kids to connect with other trans kids.“We’ll try to get them involved in these other things to sort of have that community and support,” she said.

But supplemental programming can only go so far when patients are waiting two years to be seen. “We’re just asking for more money. Continuously more money,” Dr. Olezeski explained. “More money to hire more people.” Without institutional support, trans kids like Alex will continue to stare down extensive wait times at the expense of their physical and mental wellbeing.

—Theia Chatelle is a sophomore in Hopper College. Iz Klemmer is a sophomore in Saybrook College.

**In light of the visibility of YPGP, past doxxings, and the vulnerability of trans kids right now, one source requested to anonymize identifying information in the online version of this article.