At her day job at Yale Dining, Shamica Frasier is who co-workers turn to with all birth-related questions. Pregnant co-workers consult with her on breastfeeding, mood swings, and unexpected changes in their bodies. Other colleagues solicit health advice to pass on to their wives, grandmas, cousins, and friends.

Frasier loves these questions, no matter how random or intimate. Birth is her life’s work. When she’s not at Franklin and Murray dining halls, Frasier is a doula, guiding clients through a birthing process often marred by confusion and fear.

“Being a doula isn’t just you clock in one day and clock out,” Frasier says. “You’re always clocked in.” Since becoming a doula three years ago, Frasier has discovered that everyone has questions about childbirth—especially Black families, who can receive inadequate hospital care and face grim maternal and infant health disparities.

Frasier, whose red glasses match the magenta-streaked locs that tumble over her shoulders, developed an interest in health and anatomy as a young girl. She was a teenager when she became pregnant with her first child. The birth of her second child a few years later was traumatic.

After her second birth, Frasier began to wonder: were other Black mothers experiencing similarly harrowing births? What could she do to give other people a better experience?

Researching online, she came across the term “doula,” a companion who provides emotional and physical support to parents throughout pregnancy, birth, and the postpartum period. She learned how, for centuries, births in African American communities were attended by midwives and birth companions who drew from African healing traditions.

The idea of becoming a doula captivated Frasier. As a doula, she could directly support parents like herself without incurring massive student debt to become a highly-trained medical professional. While both midwives and doulas focus on low-intervention, natural births, midwifery involves professionalized medical care. Certified nurse-midwives, the most highly trained type of midwife, must complete three degrees and pass a national certification test in order to practice. Doulas, in contrast, can become certified through a variety of different channels, including workshops, online training, and shadowing other doulas.

Frasier signed up for training, became a certified breastfeeding counselor, and eventually opened her own New Haven-based business, New Birth Journey, in 2019. Since she began practicing three years ago, Frasier has helped fifteen clients through their pregnancies.

“Being able to see moms overcome something that they fear…being able to usher them through a whole life changing experience—it’s been a love for me,” Frasier says.

Doulas have risen in prominence over the past few years, with several studies linking doula care with higher rates of vaginal births, a reduction in preterm births, and a lower likelihood of birth complications. Last summer, Connecticut Governor Ned Lamont signed S.B. 986, which will create a state certification process for doulas and provide Medicaid coverage for doula care, among other provisions. Advocates argue that the state should invest in doulas to help keep parents and infants healthy as maternal mortality rates climb and access to maternal care narrows.

The United States faces a maternal health crisis. The number of pregnancy-related deaths in the United States doubled in the last twenty years. Over the same period of time, maternal mortality in other high-income countries declined—even though the U.S. spends more per capita on healthcare.

Black and Indigenous women experience the highest rates of pregnancy-related complications, with rates of pregnancy-related deaths for Black people three times higher than the rate for white people.

As maternal mortality rates climb, people across the country face fewer options for where and how they can deliver their babies. More than one in ten U.S. counties have lost obstetrical units in the past five years. At least five Connecticut hospitals have terminated their maternity wards since 2010, many after being acquired by larger healthcare corporations.

In New Haven, the closure of the Vidone Birth Center at Saint Raphael Hospital has narrowed options for people seeking low-intervention, midwifery-centered births.

The financial push for hospital consolidation and the closure of maternity wards has made it increasingly difficult for doulas and midwives to care for low-income communities. Doulas like Frasier, intent on giving quality care to the people who need it most, find themselves working in a profit-driven system set up against them.

The Birth of an Industry

Before giving birth, patients may only see their doctor and nurses a handful of times, if at all. Frasier prides herself on working with clients from the very beginning of pregnancy to well after the baby is born. While clients are pregnant, she teaches them different birthing positions and explains what to anticipate during the delivery. During labor, Frasier is by her client’s side, whether they’re delivering in the hospital or at home. After the pregnancy, she helps clients breastfeed, watches the newborn while the new parent rests, and even does loads of laundry. Frasier’s job, as she tells it, is to help her clients feel knowledgeable about their options, especially in the hospital.

“It’s giving them that confidence to be able to not walk out with their tail between their legs, but their head up and shoulders back like ‘Hey, I have an idea of what I’m talking about,’” Frasier says. She is keenly aware of how Black patients’ voices are often pushed to the margins in a hospital setting, and how the birthing process can spin out of their control.

“There’s a cascade of interventions that often happen in hospital births that themselves can be harmful, can cause adverse outcomes—what we call birth trauma—and take away control from the patients,” Gina Novick, Associate Professor of Midwifery at the Yale School of Nursing, explains.

While such interventions, including C-sections and inductions, can be necessary to protect pregnant people and infants, unnecessary C-sections can have lethal consequences, including infections, blood clots, and hemorrhaging. C-section rates above 19 percent of live births have not been shown to improve maternal or infant health, but in Connecticut, 35 percent of births are C-sections. In 2021, the C-section rate for Black women in the United States was 19 percent higher than the rate for white women.

Jessica Westbrook, another New Haven-based doula, views herself as an advocate for clients in the hospital setting. Like Frasier, Westbrook decided to become a doula after receiving poor hospital care, feeling isolated and abandoned after the birth of her first child. As a doula, she says that she notices discrepancies in the treatment her white and Black clients receive at the hospital—even with the same provider.

“Sometimes they treat the women of color like they are just numbers,” Westbrook said. “It just seems very routine—there’s no sort of bedside manner that feels comfortable with them.” She’s observed an increased push for C-sections with her Black clients.

Westbrook described working with a recent client, a Black woman pregnant with twins. Hospital staff wanted to put her on a steroid as part of “standard procedure.” After pressing providers on why the woman needed the steroid and what the possible side effects could be, hospital staff checked the patient’s file and saw that she was allergic to the steroid. Westbrook believes that if she hadn’t intervened, the woman could have lost her life.

“Medicine is driven to look at people like a complication, like a disease,” says Lucinda Canty, a certified nurse-midwife and Associate Professor of Nursing at University of Massachusetts, Amherst. “When I was in the hospital setting, it was like a woman comes in—if she’s not really in labor, we’re going to send her home. If she doesn’t move fast enough, we’re going to have to give her Pitocin or medicine to speed things up. If she’s still not moving fast enough we’ve got to start thinking about a Cesarean. Once she comes into the system, she’s already a problem.”

Childbirth in the United States wasn’t always so medicalized. In 1900, half of all babies in the United States were delivered by midwives, who were mainly immigrants from Europe and Mexico, or Black women. Katy Dawley, nurse-midwife and professor at Drexel University, has written about how early twentieth century physicians, nurses, and public health reformers, intent on building credibility for obstetrics and bringing births into the hospital, launched a calculated campaign to stamp out Black and immigrant midwives. Advocates began writing racist and xenophobic articles that framed midwives as backwards, ignorant, and dirty—one published in Harper’s Magazine in 1930 decried “rat-pie midwifery.” Such articles ignored statistics showing that births attended by Black and immigrant midwives in the nineteen-twenties and nineteen-thirties had significantly lower death rates.

By the nineteen-thirties, midwives only attended 15 percent of births in the United States. Now, almost a century later, midwives attend about 12 percent of births in the U.S. This attendance is significantly lower than in countries like England where midwives deliver nearly half of all babies and maternal outcomes are much safer. Today, only 7 percent of midwives are Black.

Hafeeza Ture, a mother of three from a multi-generational New Haven family, can trace this shift away from the home and into hospitals through her own lineage. Her grandmother’s generation was the first to give birth in a hospital. Both her grandmother and mother used formula instead of breastfeeding. After unsatisfying prenatal appointments with an OB-GYN, Ture decided to have her children at a freestanding birth center, and then at home, attended to by midwives and doulas.

For Ture, returning to natural births felt like returning to a tradition that runs in her blood. She never had the opportunity to ask her great-grandmothers about her memories of childbirth, but she thinks about what they might have told her.

“I wish I could have sat at their feet and asked them: what was this like, what was that like?” she said. “Do you recall your grandmother’s mother?”

On the Clock

On a Thursday evening in early October, Oni Muhammad takes a brief dinner break at home before heading back to Yale New Haven Hospital to complete her on-call midwifery shift. Her day started at 8 a.m. when she attended a C-section and saw a postpartum patient. She’s headed back to the hospital at 8 p.m. and will be there until 8 a.m. the next morning.

Muhammad will be on-call for a total of twenty-four hours. She will only get paid for eight.

“We get paid more in karma, and less in cash,” she says.

Muhammad is a certified nurse-midwife at Fair Haven Community Health Clinic, a federally recognized health center. Latine activists founded the clinic in the early nineteen-seventies, frustrated by the lack of accessible and culturally sensitive care for Fair Haven’s growing Latine community. Many patients live within walking distance of the center. Today, the majority of the clinic’s patients are either underinsured or uninsured, and over half of patients earn less than half of the federal poverty line. Since Connecticut expanded Medicaid coverage of prenatal and postpartum care available to undocumented immigrants last year, the clinic has seen more than a 20 percent increase in patients.

This increase means Muhammad and other midwives at the Fair Haven clinic are working in overdrive. Five full-time midwives at the clinic work to provide continuous care, from prenatal counseling to accompanying patients to hospitals like Yale New Haven Hospital for delivery. Muhammad estimates that she helps deliver fifteen to twenty births a month. Recently, the midwives renegotiated their contracts with Fair Haven Health Clinic to decrease their on-call hours to avoid burnout: instead of a monthly seventy-two hour on-call shift, the midwives will have a forty-eight hour shift every five weeks. For their weekly twenty-four hour on-call shifts, their salaries still only compensate one-third of their hours.

“[Midwifery care] is not compensated because it’s not lucrative,” Muhammad says. “C-sections are much more lucrative from an insurance standpoint. On-call and vaginal births are just not where the money is at.”

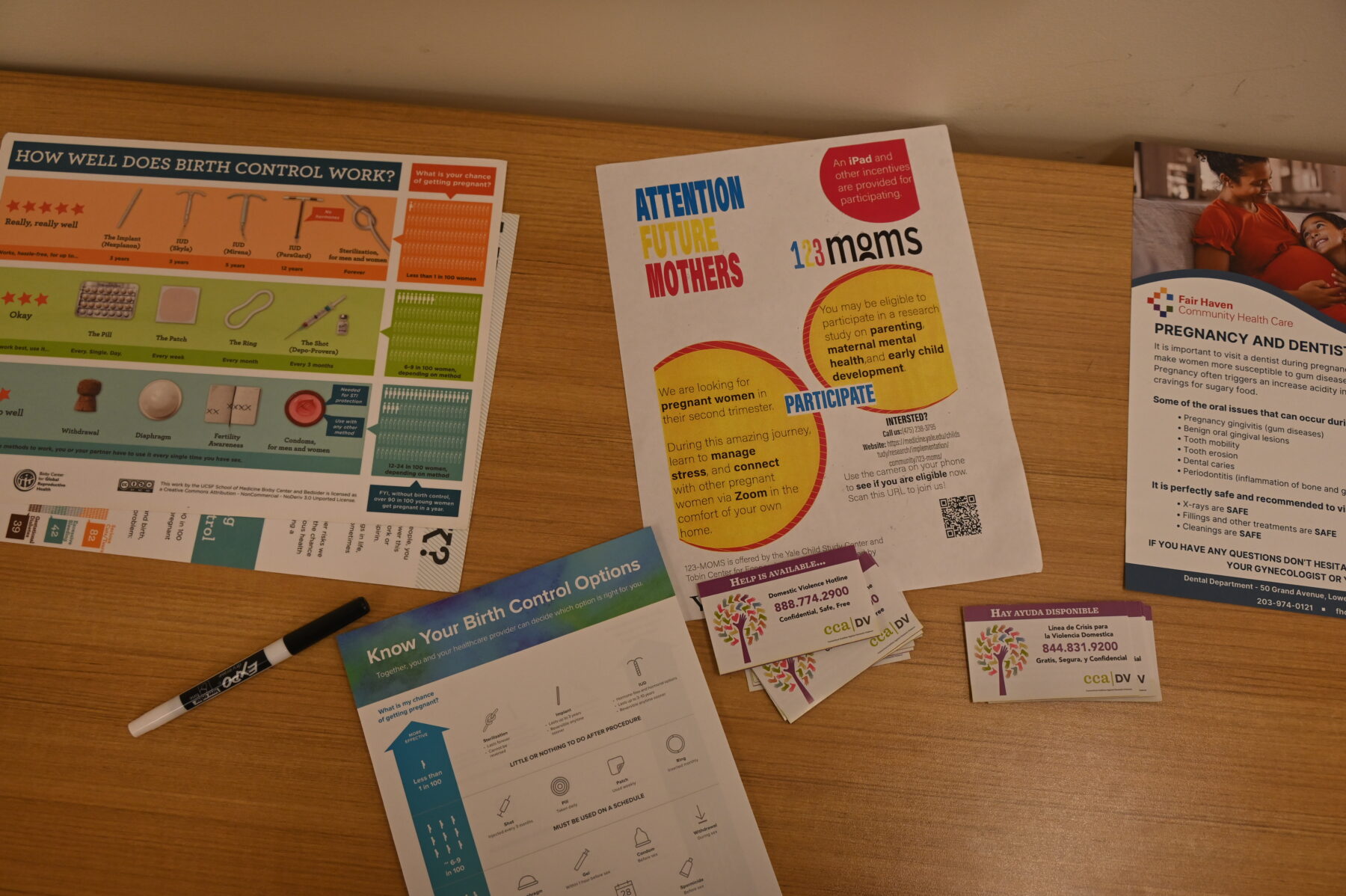

Like midwives, doulas who want to serve low-income families struggle to make a living. With S.B. 986’s implementation still in process, doulas are not currently covered through Medicaid in the state of Connecticut, meaning that hiring a doula requires out-of-pocket money. Frasier charges $700 for “Birth Support,” which includes services like prenatal visits, constant accessibility over text, support during labor, breastfeeding help, and a postpartum visit. She charges $30 an hour for additional postpartum services, and $20 an hour for lactation consultation. Frasier tries to connect clients who cannot pay with programs that will cover the cost of her services. She often finds herself drastically reducing her fees so she can provide care for the underserved Black communities who motivated her to become a doula to begin with. Still, she wonders: how accessible is her care to a teenage mom, like the one she once was?

Frasier’s dream is to quit her day job at Yale Dining and commit herself to being a full-time doula. Right now, the money is simply not there.

Growing Pains

Over the past thirty years, large healthcare corporations have engulfed Connecticut’s independent hospitals. The two largest, Hartford HealthCare and Yale New Haven Health System (YNHHS), own nearly half of the hospitals in the state. After consolidating, many hospitals cut services to cut costs, and labor and delivery is often one of the first to go.

In 2007, Hartford HealthCare acquired Windham Hospital, which had been struggling financially. In 2020, the hospital closed its labor and delivery unit. After Nuvance Health acquired Sharon Hospital, the hospital filed for permission to terminate its birthing services in 2021.

A similar story has played out in the heart of downtown New Haven with Saint Raphael Hospital’s Vidone Birth Center. Founded in 1907 as a small Catholic hospital, Saint Raphael was acquired by YNHHS in 2012. After Yale School of Nursing midwifery began its practice at St. Raphael’s the following year, the Vidone Birth Center developed a strong reputation as a midwife-centered, low-intervention birthing center.

“We really built it to thrive on a midwifery-led model of care and had excellent outcomes,” said Michelle Telfer, a certified midwife and Assistant Professor in Midwifery and Women’s Health at the Yale School of Nursing who worked at Saint Raphael. “We were drawing patients from all over the state.”

The midwifery model practiced by Telfer and other midwives at Saint Raphael focused on helping patients give birth as naturally as possible. Midwives avoided social inductions—early labor inductions performed for patient or provider convenience rather than medical necessity. In 2014, Saint Raphael established the Vidone Volunteer Doulas program which provided on-call doulas to support people during labor, opening access beyond patients who hired a doula privately. In 2015, 20 percent of births at Saint Raphael were C-sections—well under the state average of 34 percent.

In the spring of 2020, YNHHS closed the Vidone birth center at Saint Raphael. Citing concerns about COVID-19 transmission and an inability to operate two obstetric units during the pandemic, YNHHS consolidated the Saint Raphael unit with the maternity ward at Yale New Haven Hospital. The two units merged in less than two weeks.

Though YNHHS initially intended for the consolidation to be temporary, the Vidone Birth Center never reopened.

The obstetrical unit at Yale New Haven Hospital is now the largest in the state. According to Cynthia Sparer, executive director of Yale New Haven Children’s Hospital, the decision to permanently merge the two delivery units was made in order to centralize care and provide better services to both low and high-risk patients. Yet Telfer, Muhammad, Westbrook, and Frasier—along with three other midwives and doulas with experience delivering at Yale New Haven Hospital—shared that since the consolidation, Saint Raphael’s original midwifery-led, low-intervention model has dissolved. Providers and patients pointed to three central issues: a hospital layout that limits communication between nurses and residents; burnout and high rates of turnover among staff; and a pressure to speed up births, sometimes due to inadequate bed capacity.

At Saint Raphael’s Vidone birth center, one hallway housed six labor beds, the nurses’ station, and the provider call room. “I feel like it made for safer outcomes, just because we can see each other easier in a small environment,” said Muhammad, who has worked at both Saint Raphael and Yale New Haven Hospital.

Now, at Yale New Haven Hospital, nurses, residents, and private practitioners occupy physically separate rooms, and there is no room large enough for nurses, residents, and midwives to review patient records together. This distance forces communication over text from siloed sections of the labor unit instead of face-to-face discussion. Telfer expressed concern over this dependence on digital problem-solving. “I think a lot gets lost,” she said. “When you have less collaboration you have less communication, and not as good outcomes for patients.”

Telfer sees this physical isolation as a remnant of the COVID-19 pandemic, when the hospital intentionally limited contact between different providers. But even now, the separated sectors of the labor unit continue to hinder communication efforts.

“Structurally, you don’t see people. You don’t have that visual contact with people,” said Heather Reynolds, lecturer in the Nurse-Midwife Specialty program at Yale School of Nursing.

Though Yale New Haven Hospital increased its bed capacity during renovations in 2018, the hospital still sent a few overflow patients to Saint Raphael each year before the Vidone Birth Center closed. Since the consolidation, no new labor beds have been added to the hospital, meaning capacity across Yale and Saint Raphael is down six beds. Patients sometimes labor in triage because there is no labor bed available. While the triage beds are designed to “flex” into labor beds, Telfer and Muhammad said that the triage beds are not ideal for labor—there is no room for more than one support person, and laboring patients must walk through triage to use the toilet. Additionally, triage beds do not accommodate different birthing positions.

Both Telfer and Muhammad said that the shortage of labor beds can create pressure to perform C-sections. Telfer said nurses have asked her to intervene to speed up births, because there’s no time for a physiologic birth if other patients are waiting for a bed.

The stress is palpable for doulas Frasier and Westbrook. They recall providers looking overworked and understaffed when accompanying patients to Yale New Haven Hospital. Telfer and Muhammad also described an atmosphere of staff burnout and fatigue.

“Turnover has been dramatic,” Telfer said. “I barely know any of the nurses there. A lot of the ones who have been there for many years have left to do other things—they are very unhappy with the pressure and the lack of safety at times of having to care for too many people at once.”

Executive Director Sparer said that while several senior nurses left during the pandemic and there has been turnover among midwives at the hospital, retention has been very high among younger nurses.

According to Westbrook, one of the patients she was working with was scheduled for a C-section at Yale New Haven Hospital so that the birth would be over before the doctor went on vacation. State Senator Robyn Porter, whose district includes New Haven, said she spoke with a woman who felt pressured to get an epidural she did not want. A close friend, who Porter considers her non-biological niece, had a traumatic experience at Yale New Haven Hospital. She believes it resulted in the loss of her infant at five months old.

Frasier said some of her clients wanted to deliver at Saint Raphael because of its reputation for patient-centered, low-intervention care but were disappointed to learn that they no longer had the option.

“Our practice from the last few years—the midwifery model is barely there. It is a very busy labor unit,” Telfer said. “We’re not providing the kind of model that midwifery is known for and actually reduces bad outcomes—reducing unnecessary Cesareans, preterm labor, preterm birth, NICU admission—because we’re not able to give full patient-centered care experience.”

A Safe Beginning

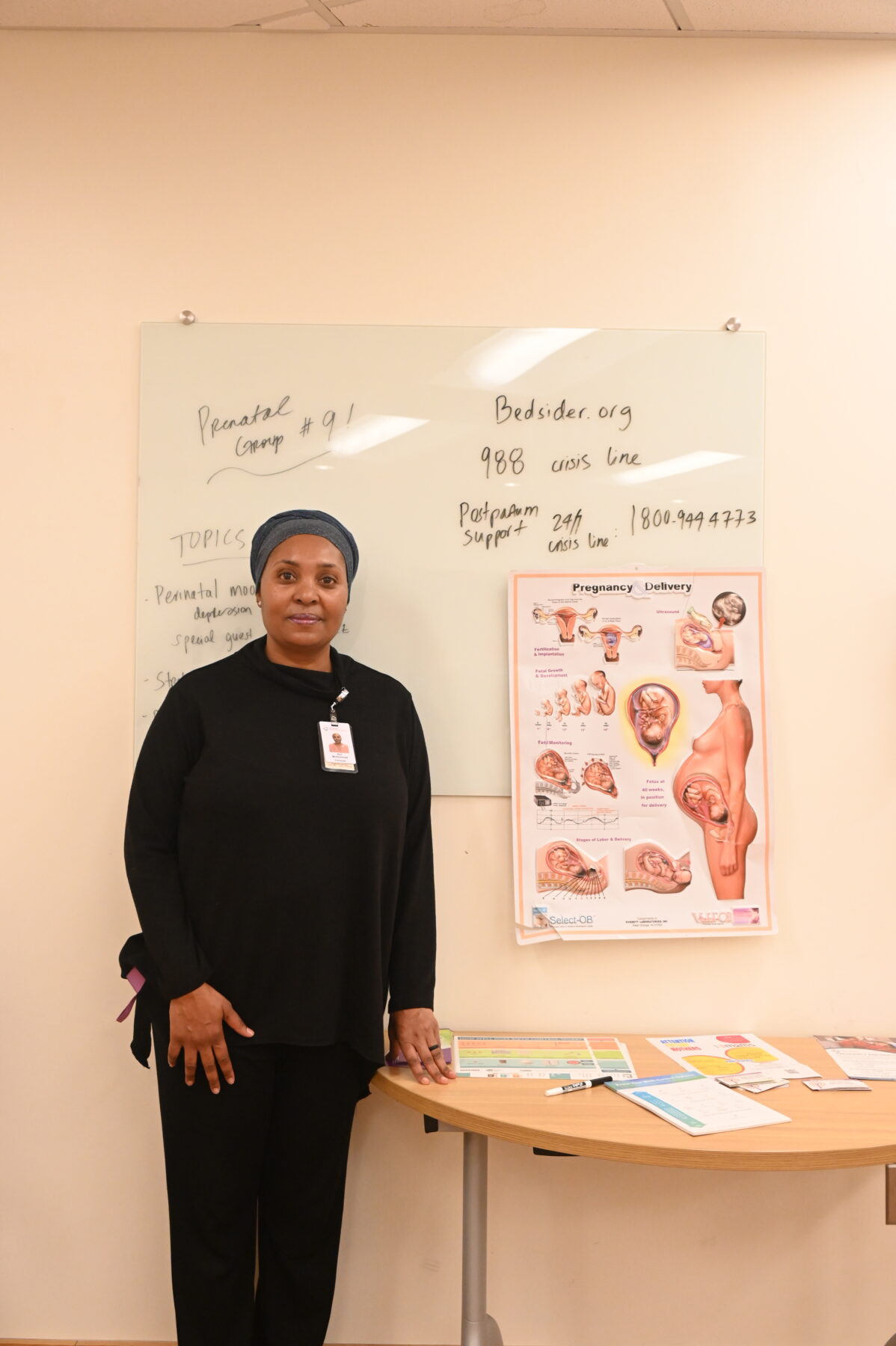

Muhammad kneels next to a woman, performing a vital check before a weekly prenatal group meeting. She and a medical assistant measure the woman’s blood pressure, pulse, weight, and fundal height—the distance from the pubic bone to the top of the uterus—to make sure fetal growth is on track.

“How are you feeling?” Muhammad asks. She wears a salmon-pink headwrap that matches her scrubs and speaks slowly, with a steady calmness. “Do you have any concerns?” An interpreter next to her translates her words into Spanish.

Next to Muhammad, the members of the prenatal group sit in a circle of chairs, some accompanied by their partners. A projector plays a video about breastfeeding on the wall. A table with tortilla chips, dip, and a veggie platter stands in the corner. In the hallway outside, a red sign reads “Keep Calm and Call the Midwife.”

The prenatal group convenes weekly to build community between parents and provide information beyond what Muhammad can cover during a twenty-minute consultation. During the sessions, Muhammad isn’t as much of a lecturer as she is a facilitator. The women share concerns they’ve noticed, such as swollen feet, brittle nails, and heartburn, and share tips and solutions.

They talk about the importance of healthy relationships during pregnancy. The final question of the day is “how would you like to enjoy the rest of your pregnancy?”

The session ends, as it does every week, with a breathing exercise. Muhammad puts on an acoustic track. Everyone stands up and breathes together: in through the nose, out through the mouth.

“This is how I want you to breathe during labor,” Muhammad says. “This is how I want you to breathe if you need to get a C-section.”

Following Muhammad, everyone in the room reaches their arms up towards the ceiling. Behind them, the guitar swells.

-Maggie Grether is a sophomore in Ezra Stiles College and an Associate Editor of The New Journal.

Photography by Nithya Guthikonda.