I left for Oxford in January of 2023, expecting that my life would be different there. I had spent the past four months in New Haven, in pain. First, it was swelling in the tissue around my heart, which left me popping a dozen ibuprofen a day to keep the feeling of a heart attack at bay. Then came the body aches and headaches, a product of stress and sleepless nights. At night, panic attacks brought the feeling that my chest was collapsing, my throat permanently closing. These were pains reserved for the United States; I imagined they would disappear on the other side of the Atlantic.

Then the insomnia came. Weeks after I could feasibly use jet lag as an explanation, I spent the hours between 2 and 5 a.m. laying awake in a suffocating room, lit only by the gray light of the low-hanging moon and the blue light of my phone screen. One night, I stayed awake simply because I was too afraid to go back to sleep. I had dreamt that my body was rotting from the soul outward, heart crumbling like stale bread, muscles going green, then black, bones eroding like brittle rocks. I woke up to stop the decay.

Excellence has always been the bar in my life.

After years of academic achievement and extracurricular success, my friends and family have begun to operate under the assumption that I will regularly do extraordinary things. Their friends know me only through their stories and have come to see me as—to quote one of them—“a unicorn.” This picture of me grows all the more mythic by my being Black and from the west side of Chicago. I’m the first person that family friends and people in the neighborhood know that has gone to Yale—whenever I come home, I field eager questions about the big things I have done and the big things I have planned. When I came back to Chicago for a few days this past summer, I ran into a friend of my mom’s on the street. He immediately introduced his children, told them where I went, and said they had to live up to what I had done with my life.

I go to a university made concrete to people from home only through movies and TV shows and rumors about the Ivy League—I have become an embodiment of their hopes. I am supposed to be the wealthy East Coaster bold enough to leave Chicago, or the Black president that actually decides to help our community, or the public intellectual doing book talks and speaking tours. Whatever I become, it must be high-profile, but it cannot take me too far from home. I should be the one they can brag about at their churches and offices, but I need to stay generous and within reach. I have to say yes to every opportunity I get, because how often do people like me, from where I’m from, get them? It’s crucial that I take risks, but I have to be so, so careful because the world’s expectations for me are much different than those of my family.

When America acquitted George Zimmerman and forced me to read those headlines with my fourth-grade eyes, the country laid the possibilities for my life before me. Criminality, death, or both. I, from the west side of Chicago, will never be the Black president who started his political career in my hometown. I, Black boy from the west side of Chicago, will find bullets in my back or handcuffs on my wrists, or both, if I step out of line. I strove to meet my community’s expectations so that I could avoid settling into the world’s.

But when you carry the expectation of excellence into Yale, it’s easy for this place to collapse your identity. My time here would only be useful if I achieved those things worth bragging about, those things which definitively placed me on an extraordinary trajectory: university awards, club leadership positions, and summer fellowships.

Back home for the holidays with my extended family gathered in our living room, I explained how getting an internship at Goldman could set us up financially for life. The days spent feeling my heart sink as I walked past partners’ offices with floor-to-ceiling windows to get to my desk and the evenings spent wandering down Lafayette Street fighting back tears were not worth mentioning. I told my family about how being one of the first two Black opinion editors at the school newspaper was an act of legacy-building––leaving out the endless evenings of lost sleep and subsequent exhaustion. To win and keep their love, I measured myself by these accomplishments. I let their visions of ivy-covered walls and centuries-old castles give me an air of intelligence and distinction I could not create with honesty. There was no space in those stories for my real self. That was relegated to private conversations with my mother and grandmother, met sometimes with sympathy, and others with the suggestion that if I just kept working, kept accumulating achievements, the pain would be worthwhile.

I was hollow when I left for England. Throughout college, I had made no genuine effort to find myself, and I thought that leaving the U.S. would finally give me the chance to do that. I imagined Baldwin in Europe, away from Harlem and unburdened by American racism, free enough to begin thinking, really thinking, about his life and the world in earnest. I imagined the same would happen to me. I expected my pain to dissolve with the weight of familial expectations, and expected I’d then grow into a fuller, more complex self. But Oxford is not a place you go to to leave expectations behind.

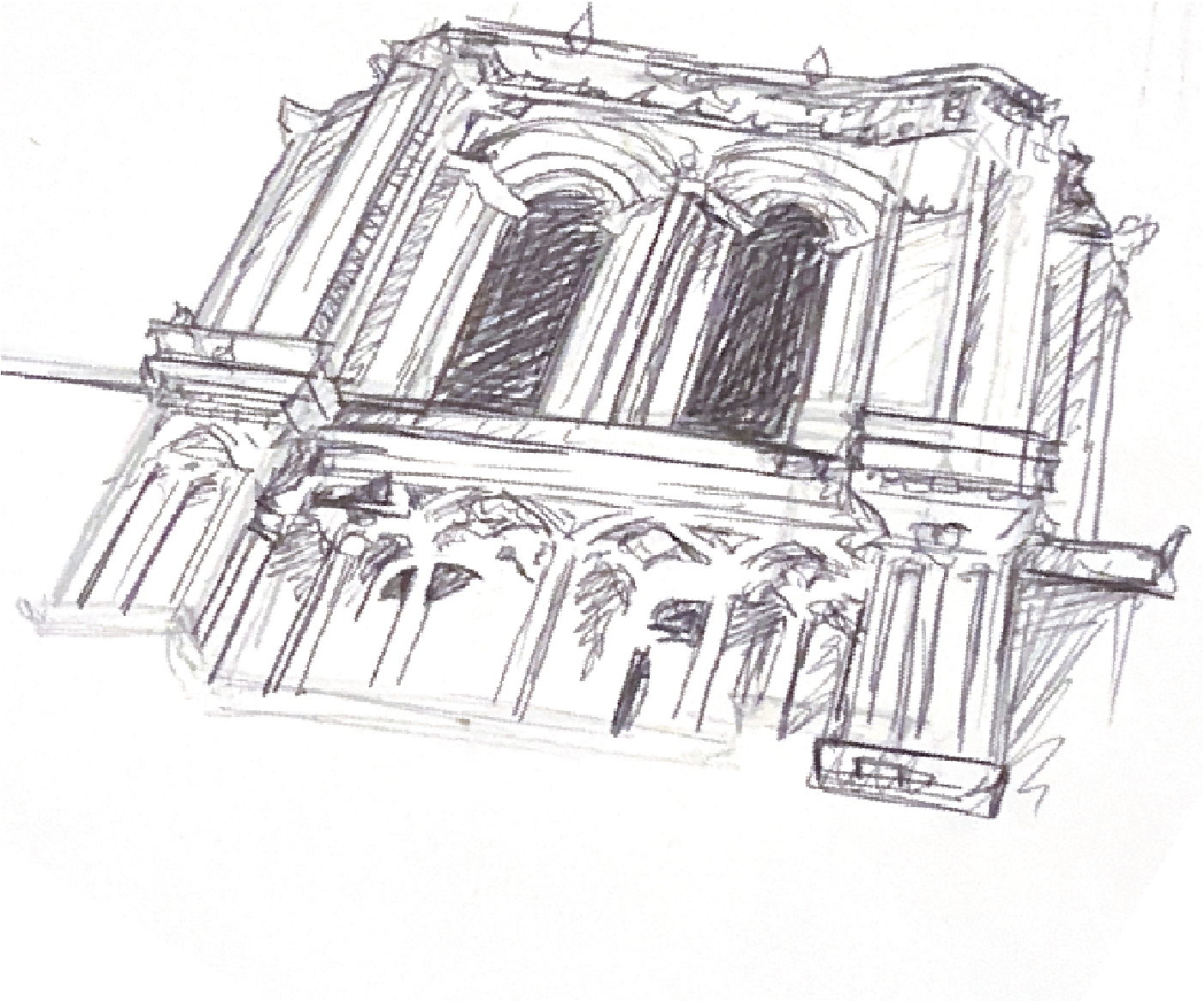

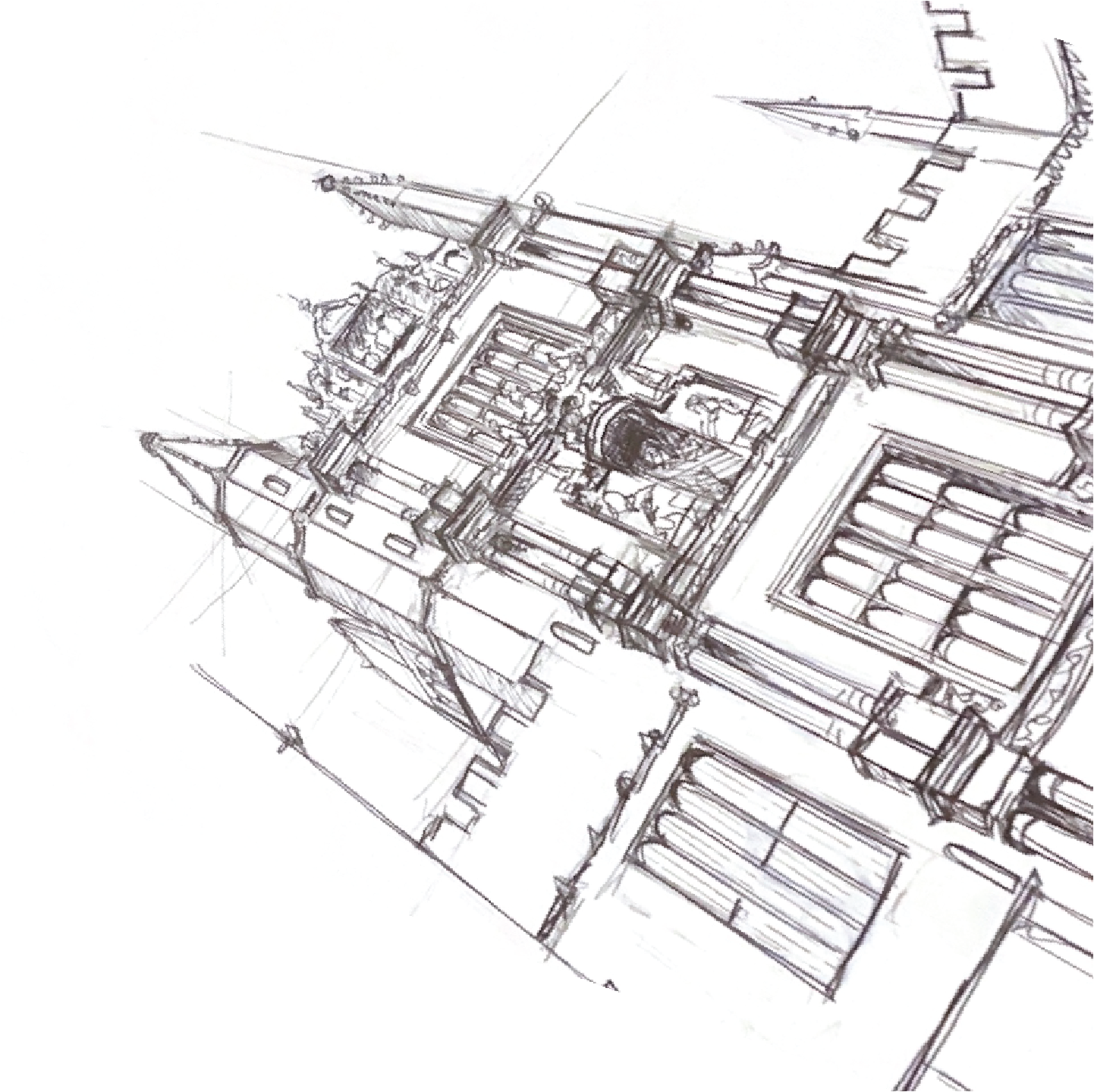

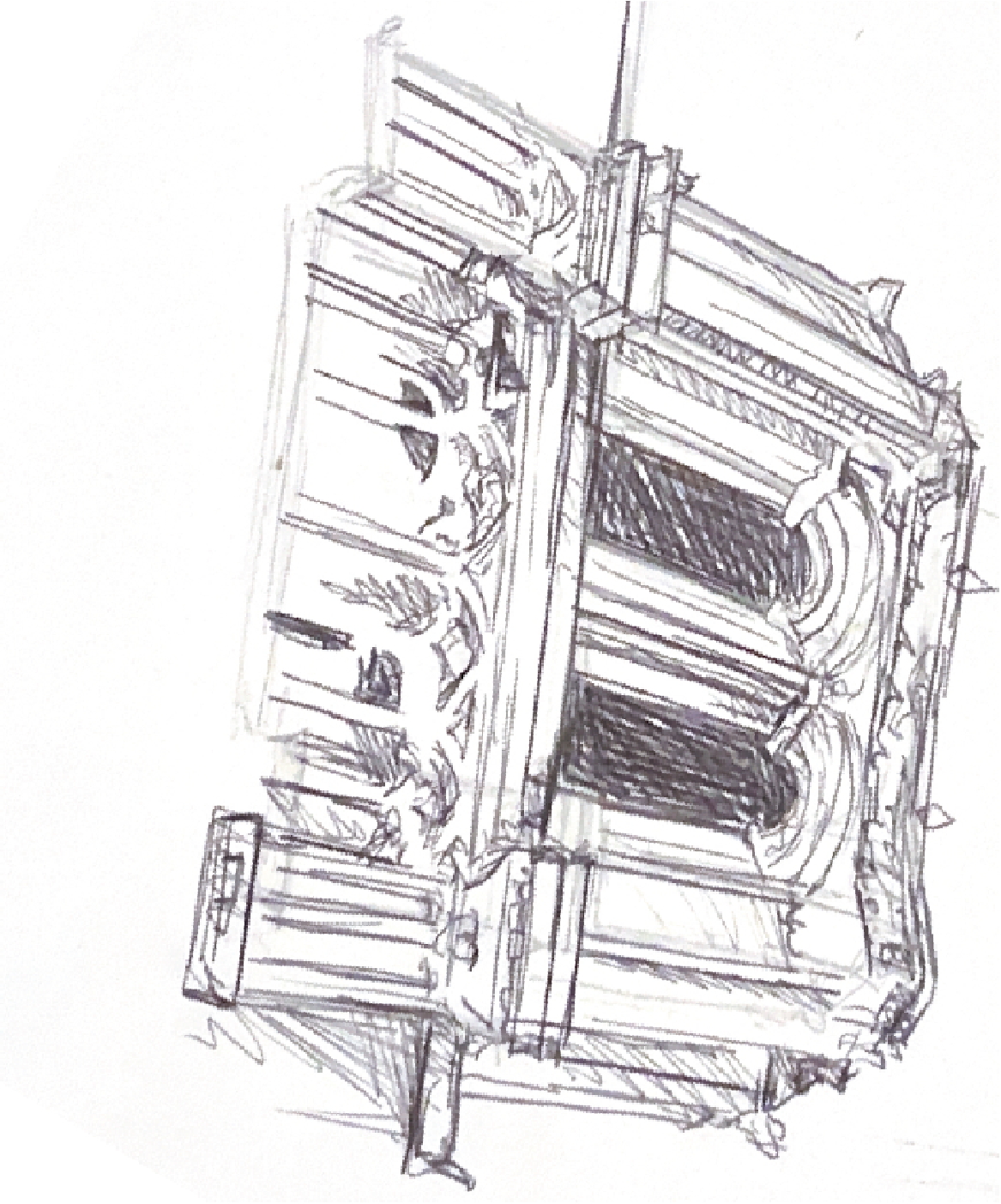

Walking past sprawling Gothic colleges and into centuries-old libraries reminded me that I was in a place of distinction, where heads of state went to be educated. Tutorials that required weekly two thousand-word essays and hour-long debates with my professors reminded me that Oxford prized displays of academic rigor. Hearing students talk about their colleges’ multi-course formal dinners held in grand dining halls and opulent formal dances held at the Oxford Union reminded me that polish and manners separated the simply brilliant from those destined to lead.

Here, unable to reach familiar markers of significance, I recognized my hollowness. This placed me on my back, in my bed at 2 a.m., fighting nightmares.

Afraid of truly reckoning with myself, I instead sought the markers of success my new environment demanded. I acted as I thought a true intellectual might, spending hours at a time poring over books and papers under the high-domed ceiling of the Radcliffe Camera. Trying to appear as cultured and well-traveled as my peers, I dragged across the continent on days I should have been resting. I thrifted button-ups, wool sweaters, and corduroy pants in my attempt to cast myself as an Oxford student. With these experiences, I could perform enlightenment, say to my family that my time abroad had changed my perspective on the world. I could tell them stories, and they could tell those stories to their friends, and we could all remain comfortable in the lie that I was, am, doing well.

On the drive from the Hartford airport to New Haven, my pain and anxiety built as the campus’s Gothic buildings came into view. By the second week of this semester, my insomnia was back. I tried to ignore my pain and continue demanding excellence of myself, applying for postgraduate fellowships to return to Oxford and continue the lie. By the end of the first month, I was dealing with headaches, dizziness, and blurred vision. I did not get those fellowships, and I am still in pain.

I have no advice to give from my time abroad. I am a senior now, and I am realizing that I cannot recover the experiences I denied myself during my time here. In those hours I am awake––two, three, four a.m.––I now think about what college would have been if I had not lied, pretending to love what I do not.

What I am left with, though, is this essay, my attempt at telling the truth. By putting pen to paper I am making myself and what I want more permanent. I am resisting letting expectations collapse my identity. And I am finally contending with the realization that I am far from where I want to be, still very much unknown to myself.

—Caleb Dunson is a senior in Saybrook College.