Beyoncé opens the show center stage, visibly pregnant. Her stomach hangs like ripe fruit, encircled by gold chains, like the ones my grandmother wears on special occasions. Do you remember being born? She asks the audience. Her voice resonates like God. Do you remember the velvet of your mother and her mother and her mother? She snaps, and backup dancers appear around her like generations of descendants. Flower petals trickle down and cover their bodies. You look nothing like your mother. You look everything like your mother. You desperately want to look like her.

And I did. I wanted to move like she did. I began to sit like she sits with her morning coffee—one foot up on the stool, the other hanging to the earth. I conjured the way soapnut essence smelled in her cupped palm. The way henna paste clumped and tangled in her hair.

Everything about my mother is beautiful in the same way everything about Beyoncé in that 2017 Grammy performance is beautiful. She’s in herself. She’s at home in her body—like the stars and trees are in theirs.

I liked the idea that I came from a lineage of beautiful people. If my mother was beautiful, so was I. If I could believe in her beauty, I could believe in mine.

There was honor in this inherited beauty, I’d decided. It was respectable, and I wanted to be respected. I wanted to be wanted.

Beyoncé’s generations spread themselves around the stage. She birthed so much time—so much legitimacy, a thing proven from having appeared again and again. I tried to mimic that with my own body—assuage my insecurities with the idea of life. In high school, I’d stare at my stomach in my bathroom mirror for hours, trying to map Beyoncé’s body onto mine. My stomach filled out three inches at its apex, a half-melon midsection.

I’d cup it with my right hand and lay my left on top, trying to imagine the truth that might flow from its fullness. I could hold beauty and life in the toughest soft parts of me. I could be beautiful like Beyoncé if I chose to see it.

I wanted to be respected. I wanted to be wanted, and there were only two ways to reach that end. The first—beauty—was an acceptance of the self without additions. It was an acceptance of history and what it had repeated. The second—hotness—was the belief that desire could only be achieved with additions. It was an allure that one could only access by putting in the effort to be different than they were. Hotness was beauty’s shallow step-sister. It was skin-deep. It was conditional. It could not last.

I accepted being beautiful for a long time. I thought I was making the good choice, but really I’d stopped believing I’d be hot. I was someone who only grasped at hotness, a lightning bug between clasped hands. I couldn’t hold it there forever. It had no malleability or stability like beauty. It could not be seen in anything passed from mother to son. So I contented myself with ideas instead of feelings—trading the visceral pleasure of hotness for the loftiness of beauty. And then I went to India.

***

The days before the monsoon comes to Hyderabad are among the hottest of the year. It’s difficult to survive the mornings without air conditioning, which is why my sisters and I were huddled around the only functioning unit. We were in our mother’s childhood bedroom. She had a plastic bag in her hands, which she tipped over and spilled onto the bed sheets. A dozen or so photo albums. My sisters and I each

grabbed one and began flipping. There were pictures from my mother’s childhood and my own. Kids in high waisted bell-bottoms and sweater vests on a balcony in Algeria. Me at 6 years old holding a Bharatnatyam pose in front of a washing machine.

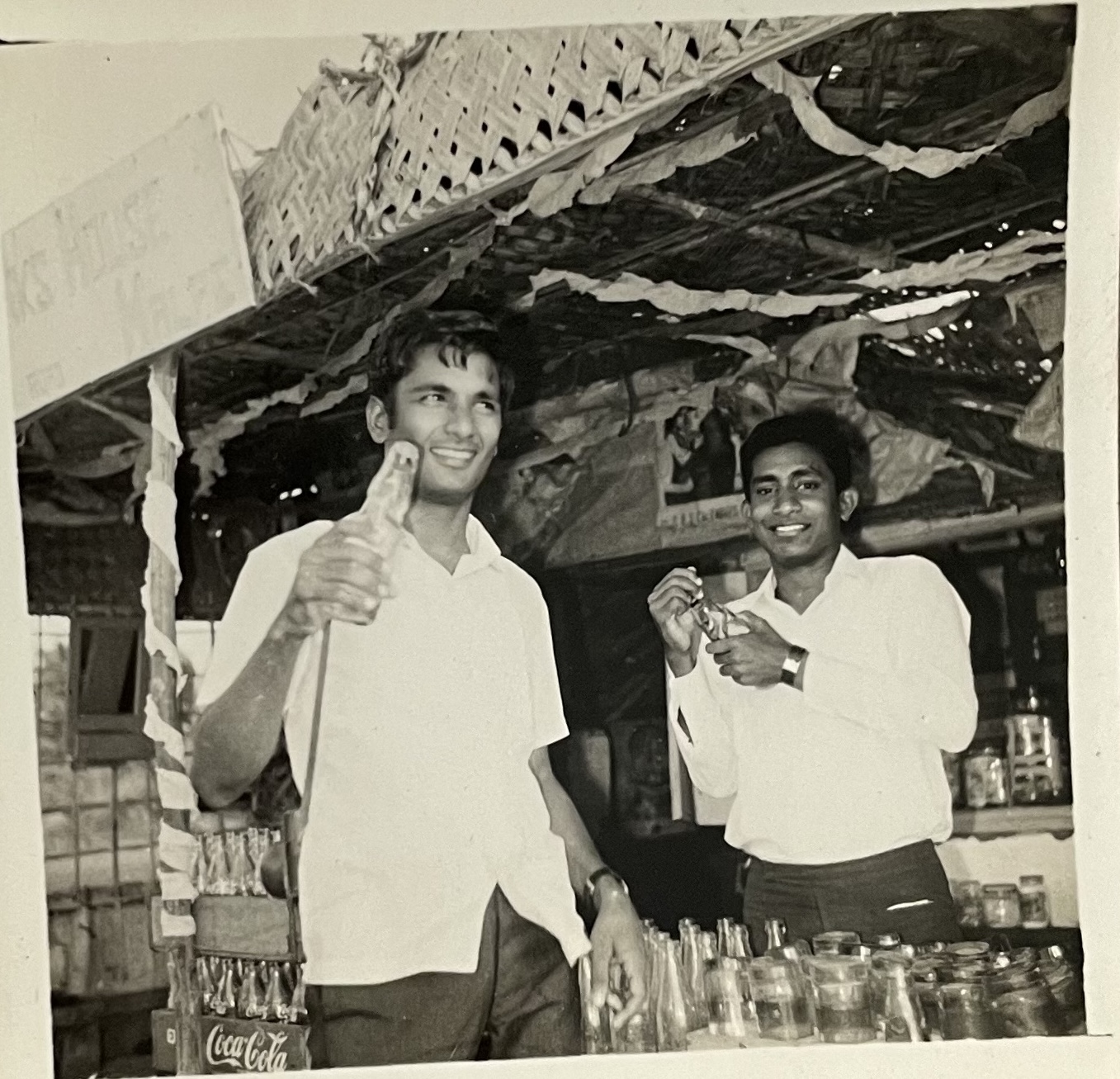

I kept flipping, further and further back in time, until I landed on a black and white picture.

In it, my grandfather is James Dean. He stands in front of a soda shop. Glass bottles blanket the counter behind him, and an awning rolls overhead. He’s looking at someone I can’t see. Another man stands behind him, looking straight into the camera, but my grandfather’s the one in the light. His skin is smooth, and his hair falls in strands over his forehead, like mine on special days. The resemblance seems to come and go. His jawline is sharp. He’s a nineteen-fifties heartthrob. Maybe this is the picture we’ll use in his obituary.

I scan this picture, think for a second, and then come to a singular conclusion.

My grandfather wasn’t beautiful. He was hot.

And then, I have another thought.

Am I supposed to be hot, too?

Cue the crisis.

I had not been born into hotness, I’d thought. But here was my grandfather, proving if not what was, then what could be. I could imagine his magnetism as mine. I remembered, then, all the times my mother had told me I was handsome like my uncle. I remembered how I’d written it off as something mothers said. How can a mother know of anything other than beauty?

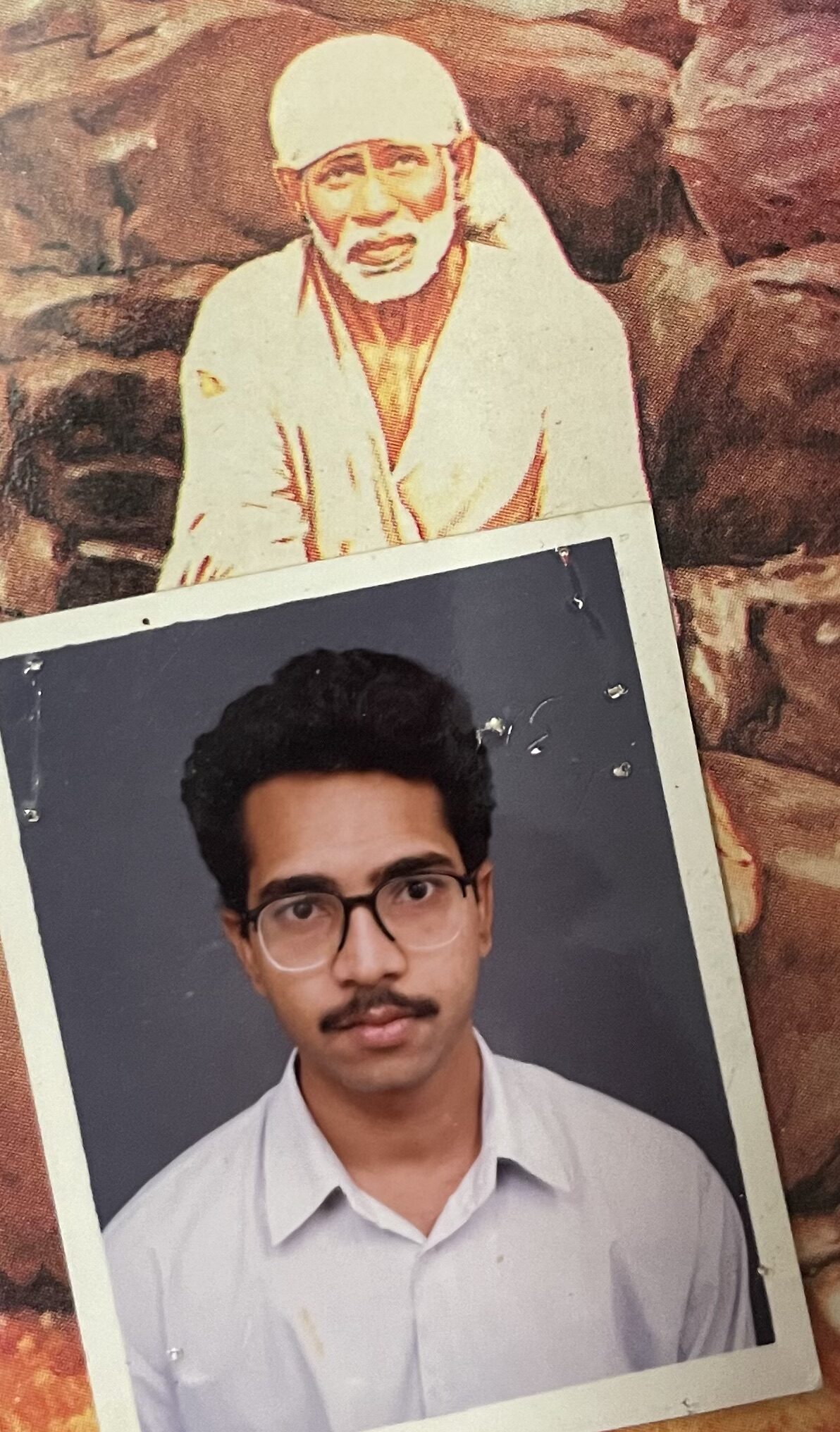

I flipped forward in the album and found a picture of him. He had the same, sharp cheekbones, and the same hair which rippled down his forehead. His skin stretched taut like I always thought mine would if I went to the gym. I paused, for a second, at this thought.

I felt a desire, then, to find myself hot. I wanted my birthright. I wanted to claim my lineage in the way I was owed.

***

A week after I held those pictures, I left India. I flew to Laramie, Wyoming, an arid town of twenty thousand. I was there for a summer internship, but what I really wanted out of this summer was to have sex as part of a short, mutually non-committal relationship with a strange (hot) man in a small town. I was proud of myself for having set a measurable goal. I reminded myself that I could be different here—this was a place of no consequence. I downloaded Tinder the night I arrived.

Looking for: Short-term fun.

I started scrolling. See, the thing that I didn’t account for was Laramine’s size and location. Oh, twenty thousand? That’s almost a quarter of New Haven’s population. I’ll be fine. Wrong. It took all of twenty minutes for Gay Laramie Tinder to run out on me. I closed the app and hoped that someone might match with me.

I went to Planet Fitness two days later. I learned to run again. Living in Atlanta and New Haven hadn’t prepared me for the rigors of cardio at 7,200 feet. I didn’t try to look good at the gym. It was a place to prepare to desire, not to be desired. I wore baggy sweatpants tucked into socks with my “I took CS50” T-shirt (or something of an equally worrying nature) on top.

A week later, my match arrived. It was one of those sure, I guess matches. He reached out first. Said Hey, what’s up. I took two days to reply. Just chilling! What about you? We sent messages back and forth until the volume of them felt like we could say we knew each other. I realized that I’d seen his face before. He worked evening shifts at the gym—stationed at the front desk every time I walked in.

We didn’t speak in real life, other than a hey, which signaled a history. Sometimes, I’d tilt my head up—craning over his coworkers to see him—and almost smile. I did not want him, but I tried to act the part.

I started dressing differently. I swapped my sweatpants out for jersey shorts with a 7-inch inseam. How my thighs curved. How my calves mounted to a peak. I became infatuated with myself and the skin I could show. Summer is a good time to be hot.

Outside of the gym, I wore the collared shirts my mother always told me would make me look powerful. Sometimes I’d wear them to the gym, if I hadn’t had time to change at home, and he’d message me afterwards. You looked good today. He reminded me that someone was looking.

I was desired, so hotness became my reality. It was something which I could exercise and embody. I had been addicted to the idea that beauty could connect me to the world, but here was hotness doing the same. Acceptance—the passive existence that beauty bought—was no longer enough. I had worked to be wanted conditionally and achieve success in the economy of desire. And I enjoyed the gig.

I feigned seduction with gym guy for the rest of the summer. He texted me, and I would text back days later. One day in late July, I opened Tinder after a week of no contact to find that his icon had vanished. I thought about seeing him again and began to work out exclusively in the mornings.

***

In late August, I moved into my house in New Haven. The school year started, and I began going to the gym regularly again. When the weather allowed, I wore collared shirts and left two buttons undone for my 9 a.m. English seminar. My roommate called it slutty.

Gradually, inevitably, the weather turned cold and cotton shirts became impractical. I layered on knit wool and began looking in the mirror less and less. What was there to see but fabric? Who was there to please with my crew neck sweaters?

Without gym guy, there was no second set of eyes grounding hotness in reality. Its allure returned to my mind, where it joined beauty in the place where images reside. It was impossible to make either fully physical and present.

It became more and more difficult to look in the mirror—to make a conscious choice in how I looked.

The picture of my grandfather ceased to be anything more than an image stored on my phone. And like that version of him, my season of hotness has become history. The age of looking is over.

—Suraj Singareddy is a junior in Timothy Dwight College and a Podcast Editor of The New Journal.