Connecticut’s Clean Slate Law promised to erase some formerly incarcerated people’s criminal records—only to leave them in limbo for more than a year.

Helen Caraballo can pinpoint the exact moment she decided she would never return to prison: her 4-month-old son’s first visit to her cell.

“Am I going to get out? Am I not going to get out? Is he going to remember me? Because he’s just a baby…he can’t hear me. He doesn’t smell me. I can’t touch him,” she rattles off. When her son was taken away at the end of the visit, her anxiety remained. “It was rough, struggling those days and nights in there and wondering what was going to happen. If I was going to come out and my son was going to be 3 years old, 5 years old, or whatever, and not remember who I was.”

Caraballo was arrested in December 2011 for three counts of a low-level felony, namely driving a vehicle with someone who was delivering narcotics to an undercover police officer. After spending three months in jail, she received a five-year suspended sentence from a judge. This meant that although she had initially been sentenced to five years, she was released from jail immediately. However, if she were to reoffend in that time, she’d have to serve the five years she’d been originally sentenced to in prison. Unlike receiving probation, the suspended sentence would remain on her criminal record.

Upon her release in March of 2012, Caraballo learned that her criminal record would stand in the way of her lifelong goal of becoming a nurse. She reached out to nursing schools and was generally advised to wait seven years before applying because “no one was going to hire me, so I would just be wasting my time and money.”

Twelve years later, Caraballo is now the mother of five children. She currently works as a patient care attendant in the Yale New Haven Hospital’s intensive care unit.

Although Caraballo’s current reality feels worlds away from her younger self’s, she continues to face the same employment-based challenges on account of her criminal record. “You have these conversations with [employers] and they see you as a person,” she said. “But when they dig into your background and that pops up, then they just look at you different…and you become a liability to them.”

Caraballo is one of many Connecticut residents who now benefits from Connecticut’s Clean Slate law, which was passed on June 10, 2021 and aims to provide formerly incarcerated people with a fresh start. The law erases all misdemeanors that led to less than one year of imprisonment from an individual’s criminal record, so long as they’ve maintained a clean record for at least seven years after their most recent conviction. Additionally, all low-level felonies and convictions leading to imprisonment fewer than five years for operating a vehicle while intoxicated will be erased ten years after an individual’s most recent conviction.

These automatic erasures will take place for all eligible Connecticut residents whose convictions occurred on or after January 1, 2000, and who have completed all of their convictions’ sentence components (prison time, parole and special parole, and probation). For convictions before that date, residents can file a petition for erasure with the court.

When Connecticut Governor Ned Lamont signed Clean Slate into law in 2021, he set January 1, 2023, as its implementation date. This was the day that Caraballo’s criminal record was supposed to have been erased. Just a month before this proposed date, Lamont announced that the law would be delayed to the second half of 2023 due to outdated technology and pending legal questions. But the state missed its projected deadline, and an entire year passed without Clean Slate’s implementation.

According to the State of Connecticut website, automatic erasures under Clean Slate are scheduled to be completed by January 31, 2024.

Initially lauded as a sweeping criminal justice reform achievement, Clean Slate has been complicated by conflicts over the law’s scope and convoluted implementation. For over a year, delays left Caraballo and tens of thousands of formerly incarcerated people like her in a state of limbo—waiting to take advantage of this second chance but continuing to face barriers because of their records.

A “Scarlet Letter”

Formerly incarcerated people face discrimination in many facets of their lives, from struggling to find housing and employment to being barred from participating in their children’s after-school activities.

Employers tend to be reluctant to hire formerly incarcerated people. In a 2019 study, 54 percent of employers said they would reject any applicant with a felony conviction for drug possession from the previous year. There were similar or higher rejection rates for applicants with recent convictions for disorderly conduct and assault misdemeanors. The Prison Policy Initiative estimated that the unemployment rate of formerly incarcerated people is between 34.9 and 37.9 percent four years after their release, which is greater than the peak unemployment rate of the general public during the Great Depression.

When Caraballo learned that nursing jobs wouldn’t accept her because of her record, she attended cosmetology school, since hair salons don’t usually run background checks on their staff. She also took on minimum-wage jobs, working as a restaurant hostess and a hotel reservation agent.

“I felt like I ruined my life,” she told me matter-of-factly. “A lot of doors closed in my face. [Hairstyling] was something that I loved, because I was doing hair since I was in high school. I was doing hair since I was 15. But I was like, ‘Am I really going to be just a hairstylist?’”

Monya Saunders was released from prison in the early two-thousands. Prior to her incarceration, she worked as a patient transport at Yale, so she decided to reapply soon after her release. Saunders shadowed other patient transports for a total of eight hours over two days and was promised the position by her supervisor, who said that she’d get her work schedule soon. After a month passed with no word from the university, she called them to ask when she’d be starting the job. She recalled being told over the phone that they couldn’t take her.

“That was devastating to me. Because they could have had the decency enough to say, ‘Hey, we pulled your background and we can’t hire you.’ [Instead,] I had to call them to see what happened,” Saunders said.

She was especially frustrated that Yale hired someone who would need to be trained for the job. “I was so emotional after this,” she confessed. “Even [now] when I talk about it, I still get chills. Because you’d rather train somebody than to get somebody who already has the experience, because they made a mistake in the past. That makes no sense to me.”

If any candidates for university jobs have criminal records, this “does not preclude employment,” according to Karen Peart, Yale’s Interim Vice President for Communications. Peart wrote in an email that Yale does run background checks on all new hires and conducts a “case-by-case analysis” of their records. Some factors the university considers include the nature and number of convictions, the relevance of offenses to the specific job, the continuity of employment before and after the convictions, the time that has elapsed since the convictions, and the circumstances of the offenses.

In addition to struggling to find employment, formerly incarcerated people often face challenges in seeking housing. Under federal law, people with certain convictions are not permitted to access public housing, and in some cases, cannot visit family members who are living there, per a 2018 report by the American Bar Association. Similar issues arise in private housing, as most landlords run background checks on prospective tenants.

As a result, new releases are not met with a stable housing reality when exiting prison. According to a 2018 report from the Prison Policy Initiative, about six percent of formerly incarcerated people are housing insecure—which includes living in rooming houses, hotels, and motels—while two percent are experiencing homelessness. Overall, formerly incarcerated people are almost ten times more likely to experience homelessness than the general public.

Caraballo slept on a couch in her mother’s apartment immediately after her release. In 2015, Caraballo was finally able to secure a one-bedroom apartment through a state-funded program that helped her put down the security deposit. “The landlord was really iffy with me because of my background, and I really had to convince her to let me live there,” she said.

After she had her second child, Caraballo decided to apply for Section 8, a housing program that provides rental housing assistance to private landlords in exchange for renting out their property to low-income households. Her application was approved and she was prepared to move to a city in Pennsylvania, an hour away from her job and home at the time. However, when she arrived at the property to discuss her application, she was turned down because of her felony conviction.

Brittany LaMarr, who was sentenced to four and a half years in prison in 2015, said the biggest challenge she experienced when she first came home was finding housing. After her release, she lived in a halfway house for a year, the first half of which she spent unsuccessfully searching for alternative housing. “It took about six months to even find a place to live and that required me to actually have to completely continue to just relive my story and why I’m deserving of just trying to have a place to live,” LaMarr said. “You have to try and convince everyone you’re not who you were ten years ago, you’re not who you were six years ago, right? And that gets old.”

Dr. Karen DuBois-Walton ’89 is the president of Elm City Communities (ECC), New Haven’s public housing agency. As federally subsidized housing, ECC is prohibited from accepting anyone who is on the sex offenders registry, those who have been convicted of manufacturing methamphetamines, and those with arson convictions. However, ECC chooses to overlook misdemeanors committed over three years prior to their application and other felonies committed more than five years beforehand.

DuBois-Walton noted how preventing formerly incarcerated people from obtaining their basic needs, such as housing, can lead them to reoffend. “They can’t get a job, they can’t get a place to live; in my mind [it] is only setting them up for failure in the future,” she said. “How are we going to expect people not to reoffend if we foreclose any way of making a positive impact in the world?”

LaMarr isn’t eligible for Clean Slate, as she was charged in 2015 for second-degree burglary—a Class C felony which is not covered by the law. She became a candidate for a pardon in 2020, which would clear her criminal record of all charges since five years had passed since her felony conviction date. Still, it wasn’t until this year that LaMarr finished her pardon application, having prioritized her work and education. LaMarr also admitted to “stalling” on the application essays due to the burden of already detailing her “transformation” countless times since returning home: “I was really just so tired of telling my story about why I deserve a second chance.”

When asked why she changed her mind about completing the application, LaMarr plainly stated that, like Caraballo, she was motivated by her children. Despite being an avid soccer player, she can’t coach her son’s team because the role requires a background check. Similarly, she used to volunteer for her son’s Cub Scouts pack but had to step down when she was asked for a background check.

LaMarr described feeling like she had a “scarlet letter” painted on her chest, which she continues to experience today: “[It’s] not allowing myself to feel like I deserve or belong to be where I am.”

Fighting for a Clean Slate

The campaign for Clean Slate in Connecticut was born in early 2018 out of house meetings held by Congregations Organized for a New Connecticut (CONECT), according to CONECT’s Lead Organizer Matt McDermott. CONECT, founded in 2011, is a faith-based, social justice organization based in New Haven and Fairfield Counties that campaigns for solutions to issues ranging from police reform to education. It is also dedicated to supporting its member congregations: dozens of local churches, mosques, temples, and other places of worship.

Every few years, CONECT holds house meetings at their member congregations. During the 2018 house meetings, participants spoke about the struggles they faced due to their criminal records. This prompted CONECT to form a criminal legal reform team, led by tri-chairs Dawn Grant, who is formerly incarcerated, litigator Philip Kent, and Rodney Moore, New Haven Healthy Start’s Fatherhood Coordinator. The team soon learned about Pennsylvania’s Clean Slate law, which the legislature implemented in 2018, and decided to focus their efforts on passing a similar law in Connecticut.

Between 2019 and 2021, CONECT advocated for three different Clean Slate bills, with the first two unable to pass in their respective legislative sessions. They were also supported by the ACLU of Connecticut’s Smart Justice campaign and Greater Hartford Interfaith Action Alliance (GHIAA), among other organizations. The first version of the bill did not pass, as time ran out in the 2019 legislative session. In 2020, CONECT and Lamont proposed competing Clean Slate bills, with the former being a more ambitious version of the current law and the latter solely encompassing minor misdemeanors and felonies. Ultimately, neither bill passed since the legislative session shut down due to the pandemic.

As it made its way through the state legislature, Clean Slate was not without its critics. The 2019 iteration of Clean Slate faced resistance from landlords due to the introduction of two closely related bills that year—SB 54 and HB 5713—that aimed to prevent landlords from evaluating criminal records as part of tenant intake.

Rick Bush, a property manager and treasurer of the Connecticut Coalition of Property Owners (CCOPO), was one of several landlords who submitted written testimony opposing the bills. He clarified that he has rented his units to formerly incarcerated people several times, including a current tenant. “The majority of people who’ve been to jail are not hardened criminals,” he said. “People just do stupid things because they’re desperate. They need money. They have kids that they need to feed.”

Nonetheless, Bush believes that landlords deserve to know their prospective tenants’ criminal records so that they can make an “informed decision.” Similarly, full-time landlord and CCOPO President John Souza emphasized that his priority is protecting his other tenants, so he’d want to know which crime a prospective tenant had committed and whether it might impact his property (e.g. a breaking and entering charge, some of which would be eligible to be erased under Clean Slate).

Both Bush and Souza stated that landlords’ main concern is having to evict a formerly incarcerated tenant. In Bush’s words, Connecticut’s eviction process is “painful, extremely expensive, cumbersome, and highly, highly weighted in favor of the tenants.” Property management software Innago corroborates his claim, estimating that Connecticut eviction costs range between $965 and $10,490 (based on how expensive the legal fees are), not including lost rent.

“Why do I want to take this risk when it’s going to cost me a lot of money?” Souza said.

By contrast, DuBois-Walton submitted testimony supporting the bills. During the past fifteen years of ECC’s reentry policies, she said that providing formerly incarcerated people with second chances went smoothly. As a result, she believes that preventing landlords from viewing their prospective tenants’ criminal records wouldn’t lead to increased evictions.

Ultimately, neither SB 54 nor HB 5713 passed during the 2019 legislative session.

In 2021, the Judiciary Committee drafted the third, and last, version of Clean Slate titled SB 1019. This bill had a narrower scope than the previous two, removing class C felonies such as LaMarr’s from the list of offenses that would be erased.

Throughout the next few months, CONECT and Smart Justice frequently engaged in “parking lot advocacy.” This involved gathering at the Connecticut State Capitol’s parking lot to implore legislators to pass the bill as they headed from their cars to the building—which was closed to the public because of the pandemic—according to ACLU of Connecticut Campaign Manager Gus Marks-Hamilton. In the meantime, the bill was amended and passed by the Judiciary Committee, the state Senate, and the House. On June 10, 2021, Lamont signed the bill into law, making Connecticut the fourth state to adopt a Clean Slate law.

So why did Caraballo wait a year to feel the relief she was promised?

Left in Limbo

CONECT’s criminal legal reform team met periodically with state officials throughout 2022 to keep track of Clean Slate’s implementation. In early fall of that year, CONECT leaders anticipated a two to three-month delay before the law was rolled out.

The bill had been delayed, according to the co-chairs of the Connecticut Criminal Justice Information System, due to substantial technical issues. In a November 28 internal statement to the Judiciary Committee, the chairs stated that the bill wouldn’t be implemented until the second half of 2023. Moreover, they requested the clarification of certain definitions and phrasing in the Clean Slate law.

Still expecting her record to be cleared soon, Caraballo applied for a role at a nursing home in February 2023 and was told she’d get the position during her interview. After she got her fingerprints taken, however, she never heard back from the employer.

“[If] the bill had passed when it was supposed to,” Caraballo told me, “I probably would have never experienced that.”

In January, CONECT leaders worked with the Governor’s Office to create a technical fix bill that would clarify some unclear wording in the Clean Slate law. Over the next six months, the technical fix bill HB 6918 was amended by and passed by the Judiciary Committee, the House, and the Senate. Ultimately, Lamont signed it into law on June 10, 2023—two years after the first bill was signed.

Throughout 2023, state agencies underwent more than $8 million in IT upgrades to facilitate criminal records’ automatic erasure, according to Undersecretary Marc Pelka. At a CONECT press conference on December 18, Pelka described these upgrades as building a “technological bridge…across criminal justice system [agencies] that were never meant to be connected that way.”

For Marcus Harvin, a formerly incarcerated man whose criminal record will be automatically erased under Clean Slate once his parole ends in 2026, the delay has deepened his skepticism of the bureaucratic system that promised to help him. “[The delay] is just probably reluctance, or fear of a public outcry,” Harvin said. “Because, let’s be honest, the public is still not fully accepting of the formerly incarcerated.”

Critiques of Current Law

Since its 2021 passing, Connecticut’s Clean Slate law has been criticized for its narrow scope. Civil rights attorney Alexander Taubes LAW ’15 pointed out that it will only partially or completely erase a “small subset of the millions of criminal records that affect people every day.”

Harvin raised the same issue, saying that people who committed more severe crimes, such as certain classes of felonies, are ineligible for Clean Slate but face more discrimination based on their criminal record. “The ones who need that redemption and that opportunity the most are the ones that are excluded at the moment,” he said. “[The law] is telling them, ‘Well, you served your time and now you’ve got to serve the rest of your life serving time in the prison of mediocrity.’”

Taubes also stated that Clean Slate should include enforcement legislation that prevents continued discrimination based on people’s records. This is particularly urgent as some landlords and employers run background checks through private contractors instead of the Connecticut government, meaning they would still be able to view applicants’ convictions which had been erased in the state criminal records. Moore suggested implementing a financial penalty to disincentivize running private background checks.

Yet Taubes highlighted that there’s no easy way for formerly incarcerated people to see when their record has been cleared. In Connecticut, people must pay a $75 fee to the State Police Bureau of Identification, as well as pay $15 to get fingerprints done, in order to have a physical version of their record mailed to them. This poses a financial burden for many formerly incarcerated individuals.

Edgar Tatum, who spent thirty-five years in prison before his release in early 2023, also thinks that Clean Slate should be supported by government-sponsored programming that facilitates formerly incarcerated people’s reentry into the workforce. Despite learning several trades during his decades in prison, including upholstery and working in a kitchen, he received little instruction on how to use a computer.

During our interview, he had trouble figuring out how to join the Zoom call and accidentally exited midway through the meeting. He described how he’s been trying to obtain his driver’s license for months but has struggled with the online course. “What good is a Clean Slate bill if no one’s going to hire you?” Tatum asked.

Despite Clean Slate’s limitations, DuBois-Walton emphasizes that the law is an important first step that can be reinforced through future legislation. “Being able to document that people’s worst fears didn’t come true… can help build the support that’s necessary to add to it and amend it and strengthen it over time,” she said. “Let’s not let ‘perfect’ be the enemy of ‘good.’”

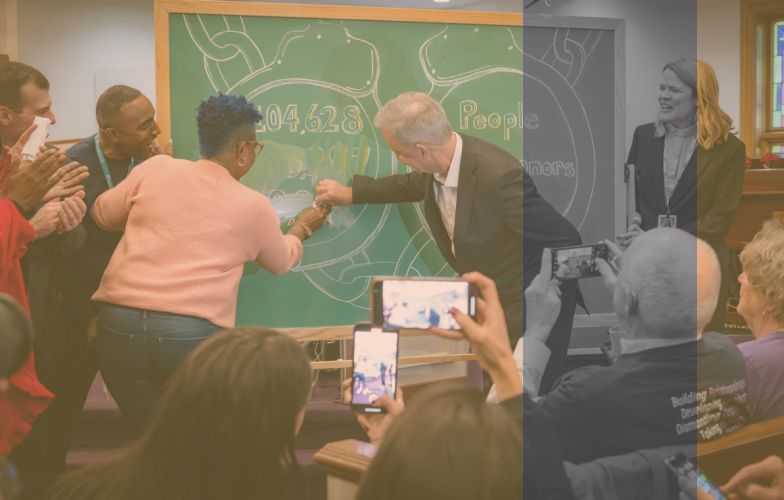

At the December 2023 press conference to announce that Clean Slate’s rollout would finally be taking place, reporters, CONECT organizers, state officials, and community members alike packed the pews of New Haven’s Community Baptist Church. Cameras flashed as Caraballo stepped hesitantly towards the microphone, wrapping her gray cardigan tightly around herself. As she spoke plainly about her imprisonment, the challenges she’d experienced since her release, and her gratitude for Clean Slate’s upcoming January rollout, she began to tear up. “This has been the best Christmas present I could have ever gotten,” she concluded with a wavering voice.

“This is not a Christmas present,” Lamont stated firmly during his remarks, addressing Caraballo directly. “This is something you’ve earned.”

Caraballo has just four prerequisite courses left at Gateway Community College before she’ll be able to enroll in its nursing program. She hopes to start nursing school in the fall of 2025—finally reembarking on the path she had been diverted from years ago.

– Maia Nehme is a first-year in Benjamin Franklin College.