Three generations of cartoonists are divided: is their craft endangered or thriving?

“Most of these people are dead,” Sidney Harris says. He points to a 1985 poster adorned with caricatures of The New Yorker’s A-list cartoonists. His portrait stares back from the center.

Death is present in Sidney’s house. He is 82. His Brooklyn accent turns “yesterday” into “yes-dud-dey” and, paired with his short stature and spectacles, cultivates a general air of curmudgeonly wit. Sidney rather resembles his characters. His most famous drawing depicts a wizened mathematician hunched in contemplation beside a chalkboard. Between two equations, he’s scrawled, “Then a miracle occurs.”

For decades, Sidney’s work appeared in The New Yorker, The Wall Street Journal, Harvard Business Review, Playboy (on far-from-sexual topics, he’s quick to point out), Physics Today and the American Scientist, among others. The Scientist––and his wife, prolific children’s book author Kate Duke––brought him to New Haven. She died nine years ago. The magazine’s cartoon section did too, several years later.

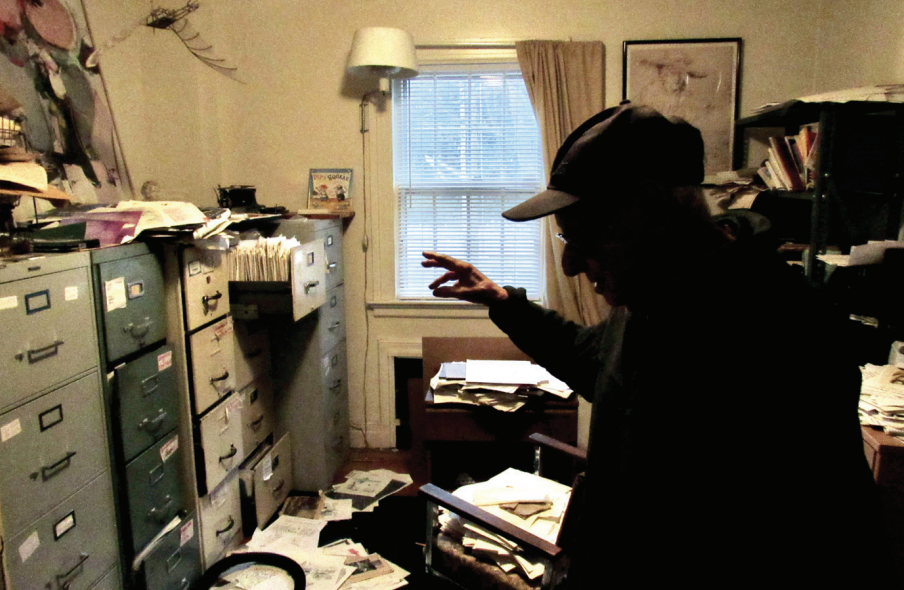

We march up the stairs as Sidney kvetches about the chilled interior. (Kvetch is Yiddish for “complain.” Sidney and I, like many cartoonists, are Jewish.) Cartoons have nearly taken over his home, scattered by the hundreds in stacks and piles, shoved onto shelves and desktops. For most of his adult life, Sidney drew ten to fifteen cartoons a week, six hundred or seven hundred a year. Each Wednesday, he “made the rounds,” marching down Fifth Avenue with a stack of cartoons to slap on editors’ desks.

Tuesday was reserved for The New Yorker, for the elite. “The waiting room was like a cocktail party without cocktails,” Sidney laughs. “Then the editor would look through your batch and say, ‘we’ll hold this one, we’ll hold that one.’ It was very competitive—it was a job.”

Pergola Des Artistes on 46th Street hosted the post-meeting lunches, a multi-generational tradition that was just as much part of the job. The long table, big enough for their group of roughly a dozen, held full glasses of French red. “I saw them for a few hours a week, and they were my family,” Sidney says. I notice the Pergola baseball cap atop his white hair. “I thought it would go on forever.”

The New Yorker submissions went digital in 2016; there was no longer a post-meeting lunch. Pergola Des Artistes closed down in 2021.

“The way I describe it to people,” Sidney explains, “I’ve never really retired, but my business retired.” When the New York native dropped out of Brooklyn College wanting to write humor, he consulted the Writer’s Yearbook, which listed publications to which he could submit. “There were pages and pages of magazines that printed cartoons––this would be around 1950.” So Sidney went with ‘toons over prose. He’d never drawn, but “somehow I felt I had a sense of humor,” he says. It was years before he sold his first cartoon for $7 and several more until he moved out of his parents’ house. By the nineteen-seventies, at the height of Sidney’s career, his middle-class wage was enough to own a house and support two children. Today, he says, “I just can’t see making a living of it. I don’t know where they could sell.”

We cracked up reading through his old idea lists. The notebook open on his desk, nearly swallowed by hardened jars of ink and stained pens, dates December 12, 1990. “I have a feeling some of these might be worth doing. But really, I’m not motivated to do it anymore. In the past few years I’ve lost my enthusiasm for doing most things.”

His apathy is not unfounded.

Magazines and newspapers are struggling. From 2002 to 2020, newspaper publishers’ revenue fell by 40.5 percent and periodical publishing by 52 percent, according to the United States Census Bureau. And, like the American Scientist, many of the publications that survive have gutted their cartoon sections, as the New York Times did in 2019. Small and local papers that still publish cartoons typically buy them through syndicates––large corporations that sell the same cartoon to multiple publications––rather than directly from artists.

There is a sense of grief among older cartoonists.

Ted Littleford, another local, 82-year-old cartoon celebrity, left his position at The Baltimore Sun in the mid-nineteen-sixties. He couldn’t support his family on his local paper salary and began art directing for New York ad agencies. Decades later, in the months leading up to the 2016 presidential election, Ted returned to cartooning for the New Haven Independent. “I saw an opportunity,” he says, to channel into illustration the existential threat he saw in former President Donald Trump.

His cartoons are not comedic––they brim with anger and grief. A two-panel, lined in black brush strokes and washed with delicate color, compares a gun trigger on the left to a woman’s pregnant stomach on the right. “America, where men are free to carry,” it reads, “and women are forced to.”

Of the cartoonists Ted knows from conventions and social media circles, many are out of work. “They were the first to go,” he says, when their papers faced closure or fired “what they considered to be unnecessary staff.” These cartoonists, Ted says, “are now submitting their work to syndicates and getting it marketed there, but it’s not the same. They don’t make the money they did before. The whole thing is tragic.”

It’s strange––to think of cartoons as tragic. But cartooning has always embodied this contradiction: it is childish and humorous, yet political and, sometimes, dark. It is math jokes and kvetching; and it is death. The dark and light, inked black and white.

Art Spiegelman’s Holocaust narrative, Maus, first published in 1972 as a strip in the comics anthology Funny Animals, introduced Holocaust discourse into popular culture and established the graphic novel as a serious literary form. In Spiegelman’s wake, there is a whole lineage of Holocaust graphic narratives. Because cartoons appear accessible, like a children’s book, audiences come to them without defenses. They’re uniquely suited to tell controversial and challenging stories.

In fact, the very first use of single-panel cartoons was political. The Harper’s Weekly cartoons of Thomas Nast, known widely as the “Father of the American Cartoon,” exposed New York Representative William Tweed for stealing $25 million from taxpayers in 1877. Ulysses S. Grant credited “the pencil of Thomas Nast” for his presidential win. Also from his pencil were born the Democratic donkey and Republican elephant as political symbols. Cartoons have a history of exerting power through their wide reach and subject matter.

Graphic art of today is no exception.

The Next Generation

“I think we might be the cartoon scene right here,” Sophie Spaner ’25 jokes as they sit with their friend and roommate Chesed Chap ’25. The three of us look like a trio of stranded Brooklyn hippies, clad in a vivid melange of ripped denim, crocheted hats, and dangly earrings. Sophie has cartooned their whole life, and grew up visiting Sidney’s New Haven studio in Erector Square. They perform stand-up, and write and cartoon for The Yale Record. Chesed has a strip in The Yale Herald, designs for the literary magazine, and performs sketch comedy.

There is a history of cartooning at Yale, Chesed reminds me. The first Pulitzer Prize awarded for a cartoon went to Gary Trudeau ’70. His first two collections, released while still in school, were comprised of strips first published by the Record and the Yale Daily News. For decades, the News published weekly editorial cartoons––as recently as 2018. Today, I am the sole cartoonist for the News.

But the cartoons that Chesed and Sophie are interested in wouldn’t be published in the News or The New Yorker.

“The stuff that inspires me and that I like to work on is the underground––the comix,” Chesed says. The Underground Comix movement of the nineteen-sixties and nineteen-seventies reacted against careful moral censoring of American cartoons by the Comics Code Authority, founded in 1954. Small presses could illegally release political, sexual, and drug-ridden narratives that violated standards set by the Authority. Journals like Zap Comix chronicled free speech and anti-war campaigns in their multi-panel strips. Zap sold its first issue out of a baby carriage in San Francisco’s hippy-ruled Haight-Ashbury district.

Today, comics are still about “liberation,” Chesed tells me. “They’re about accessibility, about class. They’re cheap, they’re easy to print, easy to distribute.” Unlike the fine arts world that is often “money-driven and hard to break into, comics––that can be anyone’s game.”

Innovative, underground art is experiencing a “weird golden age right now,” Chesed continues. Comics artists, she says, “have thrived on the small print, on self-publishing.” In February 2023, Publisher’s Weekly reported self-publishing as a “thriving” segment of the literary industry. The majority of comics Chesed reads are self-published.

Sophie agrees. “A lot of it’s online,” they explain, where artists can promote and sell their own work. “It’s often really personal art that isn’t what magazines and newspapers are interested in. I like seeing how the genre is expanding with the medium.”

Sophie is working on a long-form comic about hidden homelessness within East Coast small towns. The stories Chesed draws have helped her “process a lot of things—grief, heartbreak.” In the first graphic essay I drew, I walk through snowy woods contemplating my grandmother’s Holocaust survival––that my family walked barefoot through Polish winters to their death. Our stories are personal, whereas Sidney didn’t have “particularly strong feelings” about his subjects. Our audience, however, is smaller than Sidney’s––confined to our friends and Instagram followers.

For most cartoonists, success is to be Sidney, to be published in The New Yorker, the three of us agree. Sophie is interested in reframing this notion of success. “Don’t get me wrong,” Sophie says, “I love The New Yorker.” Chesed interrupts,“I will gladly take a job.” I side with Chesed on this one. But cartoons chosen for print, Sophie argues, must pass many levels of approval. “There’s something special about the underground comix, the raw product,” they say. “It is the truest version of what that artist wanted to put into the world.”

This authenticity––paired with a waning magazine industry––comes at a cost: the traditional cartoon career path that once existed no longer seems to be an option for young cartoonists. But this path, Sophie says “is not necessarily one I would want to follow.”

The future is open––uncertain and free. I ask if this glorious freedom is frightening. It certainly frightens me. “Oh yes,” Sophie laughs, darkly, “it scares me to the point of near illness. But I will be doing comics forever. Will it be my job forever? Who’s to say?”

A New “Graphic Universe”

Emma Allen ’10 is a big deal in the cartoon world. She is the youngest cartoon editor in the 99-year history of The New Yorker. Emma, at 29, took the post in 2017. She’s no stranger to the negotiation of tradition and growth.

“Their creators and fans view gag cartooning as an essential art form,” she writes to me. Gag cartoons, the single-panel style for which the magazine is famous, are “essential in that the medium is reflective of the aesthetics and humor of more than a century of human existence. That sounds grand, I know.” (It did not sound grand to me, a cartoon nerd whose dorm walls resemble what I imagine Emma’s wastebasket to look like.)

Gags are essential, too, to The New Yorker. “The New Yorker was founded as a ‘comic weekly,’ in 1925, and had cartoons in its very first issue,” Emma explains, “So single-panel cartoons are really a part of the D.N.A. of the magazine.”

Emma does not seem to be intimidated by this history. She sports long hair, bangs, and a pair of friendly round glasses worthy of your high school English teacher. At Yale, Emma studied Studio Art and English, wrote humor for the Record and an Arts and Living column for the Yale Daily News, and briefly wanted to be a lobster-fisherwoman. (“Then I touched a lobster,” she tells me.) Emma has brought a millennial verve and cast of diverse voices to The New Yorker.

“The universe of graphic arts is more vibrant than ever,” she writes. “I go to comics fairs, and comic book stores, or just go on Instagram and there are scores of people making and consuming drawn, narrative work of all conceivable kinds.”

Cartooning was historically very white and very male. That’s not the case in the art Emma publishes. Of the top 20 most-liked cartoons posted on The New Yorker’s Instagram in 2023, thirteen were drawn by women and six by a person of color.

I describe to her the grief that Sidney and Ted shared with me. “I’ll tell you something,” she writes, “elder statesmen and stateswomen in any industry, even financially stable ones, tend to lament the loss of the ‘good old days.’” Yet, she also recognizes that the contemporary “graphic universe” is less straightforward than before. “It used to be, you could take your dozen or so drawings for the week and stop by a dozen or so magazines and sell them all and pay off your mortgage. Losing that security has got to be very, very tough.”

Emma has an impressive capacity to bridge the old and new. She’s tapped into Chesed and Sophie’s alternative sphere of comics in a way that former editors of glossy magazines perhaps have not. Not all of today’s graphic artists, she writes, “are interested in drawing single-panel cartoons for The New Yorker—fair. But a ton of them are, and being able to bring these new voices into the fold is hugely inspiring to me.”

Most of Emma’s regulars double as graphic novelists and memoirists, like Liana Finck, Amy Kurzweil, Liza Donnelly, and Jason Adam Katzenstein––unlike previous New Yorker regulars, like Sidney, who typically published only anthologies of their cartoons. These artists aren’t exactly part of the underground, but they do bridge the historically distinct single-panel versus longform divide.

There is another thing on which Emma, Chesed and Sophie align: “I find that younger generations of contributors really never expected single-panel cartooning to be their singular profession. I have teachers and painters and ambulance drivers and zoologists submitting to me each week.” I submitted a humble batch last April from my room in Toronto.

Sidney’s “good old days” are gone. But what have they taken with them? Perhaps in the vacuum of a well-functioning status quo, a precarious, yet dynamic world has emerged.

And Then a Miracle Occurs

Affixed to the door behind Sidney’s desk are about a dozen checks. He collects funny signatures––scribbles and wobbles that lack any resemblance to written language. “Isn’t that wonderful? That is someone’s signature! You wonder, what are they thinking? Wow.” He admits, “I was always interested in crazy things.”

We have this in common—Sidney, Sophie, Emma, Chesed, Ted and I. We like these crazy things, cartoons, which exist in the inbetween, neither solely words nor images, humorous nor dark.

In the very first cartoon class I took with Amy Kurzweil, the artist who ignited my deep love of cartoons, she explained the concept of “closure.” Closure is what happens between two panels. It is what makes cartooning a collaboration between the author and the reader: in the first panel, a man touches the hat on his head; in the second, he’s holding it away from his head.

Then a miracle occurs: you see the man tip his hat. You see a world, once inert and constrained, come to life.

– Mia Rose Kohn is a first-year in Grace Hopper College.

Illustrations and photos courtesy of Mia Rose Kohn.