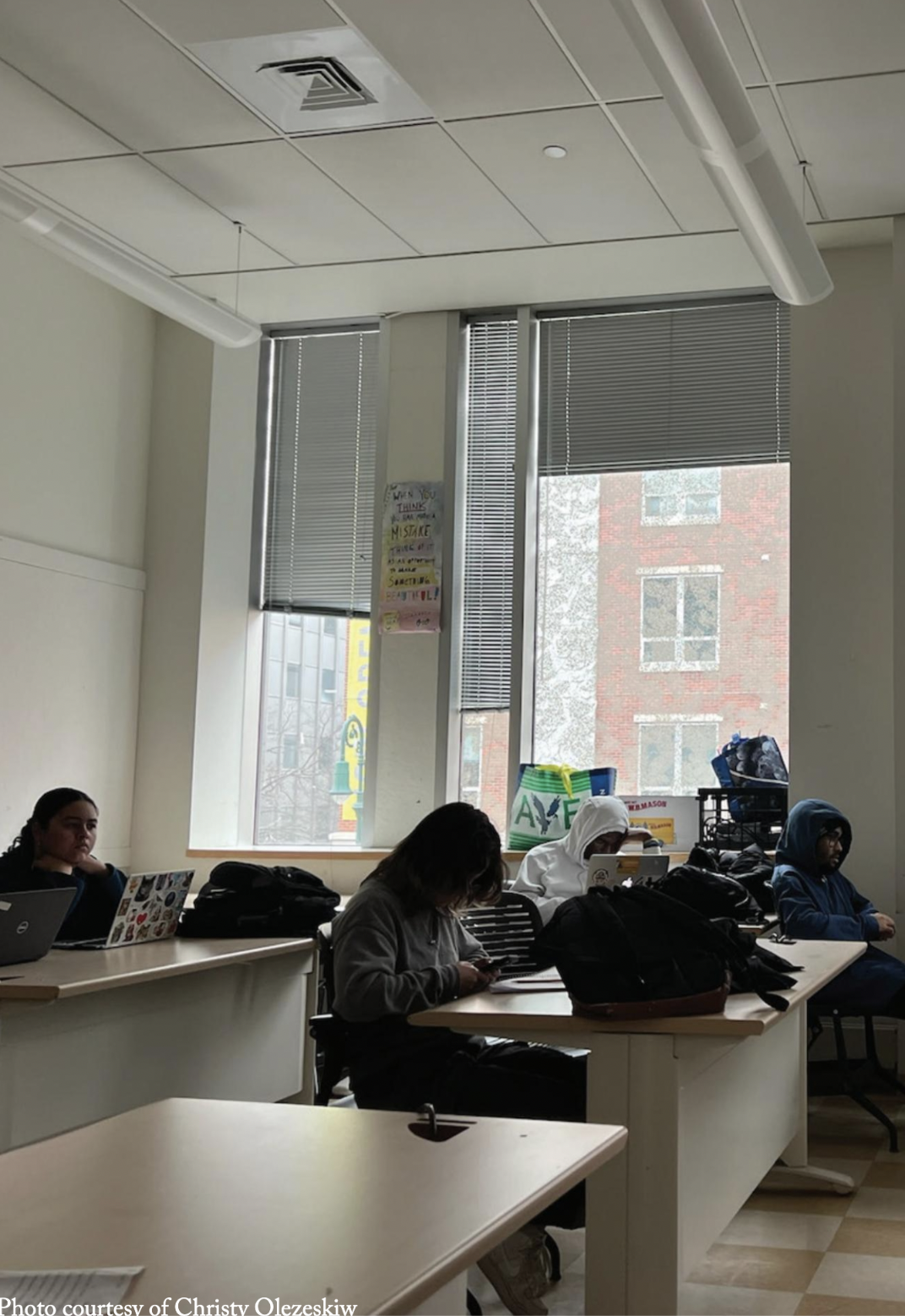

It’s last period, and students in Ryan Boroski’s “African American/Black and Puerto Rican/Latino Studies” stir with anticipation: not of dismissal, but of their in-class assignment. Students have eyes locked on their notes instead of the clock. One high schooler motions to open the conversation. Boroski reminds the delegates to shake hands out of respect, for debate, and for differences of opinion.

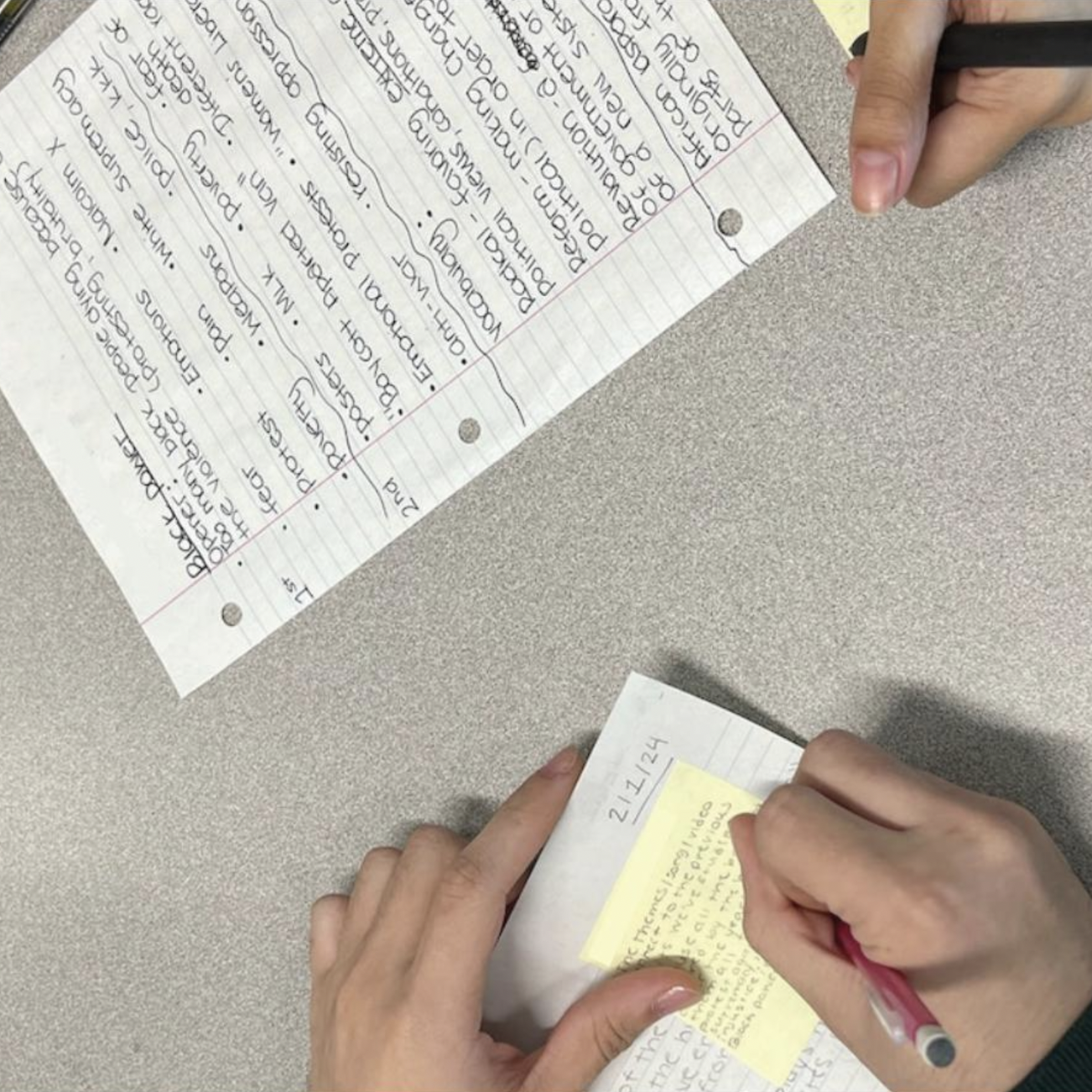

“Terrorism is an unlawful use of violence against civilians,” the student begins. For fifty minutes, a classroom of nineteen high school juniors and seniors debate the legacies of abolitionists John Brown and Nat Turner. Each team huddles around their respective table, where they hurriedly jot notes to argue whether the men should be remembered as martyrs or terrorists.

“Maybe violence was the only answer they had,” one student ventures from the four speakers’ chairs, clustered in the classroom center. “They admitted to murdering people who might not have had a place in this,” another student rebuts, “Martin Luther King [protested] peacefully…there were better ways to do this.”

Between designated speaking times, delegates deliberate these violent rebellions with their peers.

“Was it inevitable?” “Was it just?” Through the thicket of conversation, I hear mentions of the Emancipation Proclamation, Al-Qaeda, and congressional hearings. The upperclassmen’s arguments pull from a vast bank of historical knowledge.

When College Street car horns start blaring, the students peer out the window to investigate the commotion. Boroski quickly pulls the room back to focus. “I have no clue what goes on in downtown New Haven,” he says, “We can only control what goes on in here.”

Boroski moves the conversation into modern terms, comparing the violence perpetrated against Planned Parenthood centers to the violence perpetrated by Nat Turner and John Brown. “[Are] those people in modern times that use violence at Planned Parenthood places…justified in their actions because they are also acting on behalf of what they think is right?”

Five years ago, this debate would likely not have occurred in a Connecticut high school classroom. Boroski has been teaching the state-mandated ethnic studies class at the Cooperative Arts & Humanities Magnet High School (Co-Op) in New Haven since 2021. The elective is composed mostly of juniors and seniors who are interested in learning about Black and Latino histories. A 2019 bill made Connecticut the first state in the country to mandate the inclusion of ethnic studies electives in its high school curriculum. Classes like Boroski’s are available to high school students across the state.

The same year Connecticut piloted the country’s first state-mandated offering of a Black and Latino studies elective, ten states—particularly in the Midwest and the South—passed censorship bills to ban “divisive” discussions of institutionalized racism and Critical Race Theory in both K-12 and college classrooms. Americans have long been conflicted on how to teach race and history in classrooms. These most recent debates follow a long lineage of “culture war” rallying cries on topics ranging from religious education, sexual education, LGBTQ+ rights, and racism that often play out in schools. Educational initiatives that question Eurocentrism, cultural relativity, and the democratic principles of the founding fathers have sparked backlash from outspoken critics (in 2019, The New York Times’ “1619 Project,” which asserted that America began when the first enslaved Africans arrived, was countered by “The 1776 Project,” a conservative retelling of history since America’s founding). The fixation from all parties reveals that schools are more than just spaces to transmit knowledge; classrooms can be battlegrounds for defining America.

Including Boroski, I spoke with four New Haven Public School teachers, a dozen of their students, and an additional nine advocates about the passage of a bill that has the potential to set a precedent for public education in America.

Building the Bill

On June 21, 2019, Governor Ned Lamont approved the incorporation of “Black and Latino Studies” in the Connecticut public school curriculum with the passage of Public Act No. 19-12. The bill received strong support across parties, with a vote of 122-24.

Boroski attributed the bill’s near-unanimous endorsement to Connecticut’s strong Democratic-leaning demographics: “I think [our] side of politics is not afraid to learn true American history, and other states are.”

Though the act passed with little resistance, it took advocacy from students, teachers, and parents to push the issue to the legislature and ensure its efficacy.

Benie N’Sumbu, a 2019 graduate of Co-op, testified in front of the Education Committee to support an earlier iteration of the bill in the spring of her senior year. On behalf of Students for Educational Justice, a youth-led advocacy group based in New Haven, N’Sumbu expressed concern about how Black history was taught in school: “Just a few years ago, people were talking about how slavery was a choice and how they didn’t fight back, which is so not true.” She hoped the course would introduce an “untaught history” to schools, with lessons that could challenge biases in conventional curricula through active student engagement, not simply “fact regurgitation.”

N’Sumbu’s sentiments were affirmed by the results of a 2020 survey conducted by the curriculum’s Advisory Group: a third of Connecticut high school students polled were interested in acquiring “a deeper understanding of inequalities and understanding of racism as a social construct.” According to survey results, students were particularly interested in learning the “real” history.

From 2019 to 2021, the State Education Resource Center (SERC) partnered with the Connecticut State Department of Education to develop a curriculum for the new course. SERC members said they hoped to create a program that would set a new precedent for learning, deviating from a Eurocentric framing of Columbus’s New World landing and European colonization as the start of American, African, and Latin American history.

During the program’s development, rising instances of police brutality and subsequent protests made systemic racism visible and Critical Race Theory a popular debate in mainstream media. In Connecticut, right-leaning politicians and parents rallying against the program weaponized misconstruals of Critical Race Theory against educators who were attempting to elucidate race, racism, and identity in K-12 classrooms, particularly in wealthier suburbs. In Easton, residents put up anti-CRT signs, and in Guilford, nearly five hundred people petitioned to ban social-justice indoctrination in their public schools.

The State Board of Education approved the final course, “African American/Black and Puerto Rican/Latino Studies,” on December 2, 2020. The curriculum was not approved solely to cover racism—N’Sumbu and her co-organizers at SEJ were concerned that a class with “Race” in its title would not pass statewide. But consultants at SERC told me they had every intention of creating a new type of class to address the history of racism in the U.S.

The course intends for students to work intimately with the material. Most of the assessments are journal- or discussion-based, culminating in classroom essays and debates. Only twice does SERC’s curriculum mention the word “quiz,” and never “exam.” Paquita Jarman-Smith, the SERC Consultant responsible for the African American/Black studies portion of the curriculum, said that she and her colleagues prioritized activity-based learning to engage students beyond memorizing facts. The curriculum also outlines a semesterly class project, where students collaborate with other school departments, like Art, Music, and English Language Arts, to creatively present their imaginings of justice based on the year’s teachings.

Starting in the 2021 to 2022 academic year, school districts across the state of Connecticut were invited to teach the pilot program. The year-long course was divided into two semesters. The first chronologically taught African American and Black history, from ancient African kingdoms to the Jim Crow era to the modern Black Lives Matter movement. The second centered a thematic focus on Puerto Rican, representing 74 percent of the Hispanic population of Connecticut, and Latino Studies, touching on Indigenous erasure by Spanish colonizers, U.S. colonialism, and the diversity of Latino identity. In the fall of 2022, all Connecticut high schools were required to include the elective in their offerings.

The developers of the course expressed their pride in this achievement, saying, “Each day we are just enamored with this.” When asked about the feedback they received on the program, Jarman-Smith, Diaz, and their colleagues at SERC agreed, “All students should have this course.”

Opting In

Student organizers, SERC, and their Advisory Group felt that pushing for all schools to require the course would have placed excessive pressure on its broader school districts. This is especially true in light of Connecticut’s recent amendments to high school graduation requirements, where students need to obtain twenty-five credits instead of twenty credits to graduate. Legislators and organizers hesitated to impose further changes on schools.

With the course ultimately being an elective, however, the educators I spoke with were concerned that not all students can make room to take it.

“Electives compete with other classes for students,” said Ben Scudder, who teaches the course at High School in the Community. “Students are picking between this and P.E. or art.”

Moreover, they voiced concerns that it would self-select students with prior interest instead of those who already felt disconnected from the material. Throughout the New Haven school district, 89 percent of students identify as non-white, with 48.1 percent of all students identifying as Hispanic or Latino, and another 35 percent identifying as Black or African American.

Jessie Piper, who teaches the class at Metro Business Academy, also noted varying levels of interest in the course. Piper told me not all students in her class take it on their own accord; some are placed by guidance counselors for scheduling purposes. “I’m worried that the people who don’t care will weigh down the people who do care,” she said. Moreover, the class was designed to be inclusive to students of all learning levels, so some students with less prior knowledge might have to learn the material at a faster pace than others.

Still, each of the four classrooms I visited had students who attested to the value of the course.

Boroski’s junior students at the Co-op affirmed the class’s in-depth nature. Farida I., one student, spoke on the curriculum’s ability to transform challenging topics into accessible ones. “It’s a mix of jokes,” Farida said. “Then we get into the serious stuff, then we cool down and discuss.”

Drew W., a sophomore in Piper’s class at Metro, found the second-semester curriculum especially rewarding. Growing up Black in the South, she had accumulated a knowledge of Black American history but had received less exposure to Latino culture. She cited the border system, Christianity’s diffusion throughout Latin America, and the tenuous relationship between Puerto Rico and the U.S. as crucial facts the course had taught her.

But Drew also expressed confusion on why this cultural history course was separated from the core U.S. History curriculum. “It’s kinda ridiculous that we even have to have this class when this history is literally American history,” she said. “Why is this not just a part of the regular history curriculum? It’s like they’re othering [people of color]. It’s like ‘This is the history, and there’s no room for you.’”

Teachers Taking Liberties

I visited A’Lexus Williams’s classroom at Hill Regional Career High School the same day I visited Boroski’s classroom: February 1, coincidentally the first day of Black History Month.

That day, Williams had created a presentation for the last unit of the first semester, “Protest, Politics, and Power (1965-Present).” It included songs like Sam Cooke’s “Change is Gonna Come,” Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Goin’ On,” and a 1964 speech by Martin Luther King Jr.

Williams weaved through every corner of her large classroom to address her eleven students. She moderated the discussion closely, but many of her students were excited to jump in.

Williams, who is Black, confidently projected to her class of entirely Black and brown students. On the whiteboard, she defined the word radical and said: “The audaciousness for Black people, free and enslaved, to call for the abolishment of a system that had been sustained for hundreds of years was considered radical.”

Wesley R., a senior in Williams’s class, felt the class was more freeing than the fast-paced STEM lectures he was used to. “Our ideas just come out, and we talk based on what a peer might say,” he said. “In other classes, we’re quiet unless a teacher picks on us.”

Later that same day, Boroski and his students conducted their final debate of the semester, projected in front of the room: “Were John Brown and Nat Turner American martyrs/heroes or terrorists?” Through laughter and earnest deliberation, Boroski’s students all participated in the assignment with uniform engagement and enthusiasm.

On the same day, following the same state guidelines, Williams and Boroski taught two different classes in two different styles.

“We offer and guide [Connecticut schools] to follow the course and follow [its] fidelity,” SERC’s Jarman-Smith told me. “But school districts have to make it theirs.”

A few years prior to teaching this course put forth by SERC, Boroski and his colleagues had been asked by Co-op principal Paul Camarco to develop and teach a class on African American and Black history. Boroski developed the course, which he recalled teaching from 2017 until 2021, by asking his students what they envisioned. The result emphasized modern figures and events, a practice that he has carried into implementing SERC’s program.

“[Students’] personal experiences tend to relate more to current events and injustices,” Boroski said, “police brutality, mass incarceration, war on drugs…”

Straying from the statewide curriculum, Boroski asks his students to research examples of modern-day slavery or the stories of unheralded Americans like queer activist Marsha P. Johnson. He wants his students to discover what makes them curious, and what makes them uncomfortable: “If you give students meaningful choice [over] what they learn, they’re more likely to take ownership of their learning.”

This style seemed to resonate with some of his students. “[The content] is not just facts and dates, which don’t connect with me easily,” Juliet S., a senior in Boroski’s class, said. “We talk about the mistakes of the past.”

This standardized curriculum can look so different between two schools in part because following SERC’s program in its entirety can be overly ambitious for educators.

“The curriculum is so dense [and] pacing in the curriculum underestimates certain lessons,” Williams said. Scudder and Piper agreed that it is infeasible to cover all the content in one year.

As a consequence, teachers have assumed the liberty to modify lesson plans according to their educational interests and understanding of their students’ learning paces. “I’m looking at it as a course that opens a lot of opportunities,” Scudder said. “It’s not beholden to anything; there’s no AP exam at the end.”

The class looks different everywhere. Teachers facilitating the course throughout New Haven public schools don’t communicate directly—when asked if they knew anyone else who taught the course, the teachers I spoke to struggled to come up with a name from any of New Haven’s nine public high schools. According to Williams, the history departments across the schools meet once a month for only an hour. There is no set time for the African American/Black and Puerto Rican/Latino studies teachers to meet. As a result, the program can vary in content, pacing, and methodology from county to county, school to school, classroom to classroom.

Despite this lack of inter-district communication and consistency, Williams noted a shared experience among teachers in the district. “We’re definitely on the same page on how dense [the program] is, but we have to do what is in the best interest of who is in front of us.”

Training Teachers

Public Act No. 19-12 does not mandate an additional certification for teachers to instruct the course—any high school social studies teacher can teach it. But in its public digital copy of the curriculum, SERC publishes hyperlinks to databases, articles, and activity lesson plans. They also host a summer institute, quarterly trainings, and an end-of-year showcase to prepare teachers and track progress.

Williams opted to attend a professional development seminar hosted by the Anti-Racist Teaching & Learning Collective (ARTLC). The initiative is a collaboration between Yale professor Daniel HoSang; Students for Educational Justice; Hearing Youth Voices, a youth activism group based in New London; and local educators. Members of ARTLC had expressed a wide array of concerns about the bill: that it would mandate an inflexible curriculum that would “displace existing teacher-developed courses,” fail to prepare teachers, employ ineffective and impersonal methodology, and silo African American and Latino Studies with each semester’s structure. ARTLC offers solutions in their anti-bias and anti-racist oriented teaching guides, lesson plans, webinars, and in-person seminars for those teaching the course.

Williams acknowledged how ARTLC’s resources help empower teachers to feel comfortable having the difficult conversations that emerge from course questions. “Having that [professional development] allowed my white colleagues to think it is okay to maybe say the wrong thing,” Williams said. “Now they know how to move forward. We’re not gonna get into that white defensiveness.”

Scudder and Piper also mentioned finding these resources through colleagues and friends who were already involved in ARTLC. Similarly, Boroski expressed taking additional steps to learn beyond the scope of SERC’s recommended training, such as researching books to include in his lessons, like Dear Martin by Nic Stone and The House on Mango Street by Sandra Cisneros.

“Training is like ‘Let’s go through the curriculum in a week,’” said Scudder. He said the difficulty of the topics is not matched by the quality of training, which largely reiterates SERC’s publicly available material. To him, this cannot sufficiently compensate for every background discrepancy. “I didn’t major in Black or Latino history,” he said. “I majored in political science…There needs to be a greater discussion of what this class will look like.”

White teachers, POC Students

The deeply personal themes of the course, paired with varied implementation and levels of training, mean that student experience depends more than usual on who is teaching and how.

While 89 percent of the students in New Haven Public Schools are non-white, only 28 percent of teachers are non-white. Williams was the only non-white teacher I spoke with.

This discrepancy is no anomaly in the history of New Haven Public Schools. N’Sumbu said she never had a Black teacher in her time at Co-op. Drew added that the students are aware of this disparity: “Especially with the history that we know between white people and Black and brown people, it feels questionable at times to have a majority Black and brown school and basically, all the staff be white.”

This divide is not lost on the history and social studies teachers of New Haven. Boroski said that for his class’s first discussion, he wrote a question on the board: “How do you feel about having a white teacher teach this class?” While he received a mixture of positive, neutral, and negative responses, Boroski took the opportunity to hear his students and, together, negotiate best practices for learning heavy content.

Juliet, who is Persian and one of the few students in Boroski’s classroom to not identify as Black or Latino, told me, “Boroski makes it very clear that we all have a voice here.”

Piper had also welcomed the subject into her classroom. “You’re white and why are you teaching this class?” she tells me her students have asked. She says she responds: “It’s history, and you don’t have to personally live history to talk about it.”

One of Piper’s senior students, Alysian M., said she’s glad that Piper is the one to teach the course. Alysian identifies as a biracial trans lesbian, or, as she puts it: “a lot of different identities hodgepodge together.” Alysian sees her own history in the course, in discussions of struggle ranging from African American history to the Haitian Revolution.

“Learning about [slavery] makes me feel closer to history and people around the world and struggling with an oppressor,” she says. “Despite race, nationality, gender, and sexuality, everyone has had somebody who’s bullied them…Overcoming that oppression, that’s what attracts me to the course.”

As students learn, the teachers in front of them consider their own roles.

“I’m trying to think of myself as less [of] a teacher and more as a facilitator of discussion,” said Scudder, whose sentiments were shared by the other white teachers I spoke with who are teaching the course.

Williams, who is one of two women of color in her seven-person department, believed that that attitude might distill classroom discussion. “The white teachers who are teaching this course probably are worried about saying the wrong thing or don’t know how to have these conversations about race,” she said. “They don’t want to upset their students or perpetuate something.”

Wesley noted how that representation was important to him and his classmates: “[Williams] is someone who has felt disparities…since she looks like us, we feel like what we’re being taught is more personal in that way.”

But regardless of background or identity, Williams acknowledged that everyone has something to learn from the course. “I’m the first to tell my students that just because I am Black does not mean I know everything about Black history because we are not monolithic,” she said. “There are things that I’m learning and unlearning and considering other perspectives as we go through this together.”

Williams recalled an unexpected learning experience for her in her classroom. One day, she presented a recent court case to her class regarding a Black student who was suspended by his Texas high school for refusing to cut his hair. She intended for the case study to demonstrate the future of Black excellence and beauty, incorporating the idea from previous units of race as a construct. In response, one of Williams’ students asked whether or not he would cut his hair when he entered the workforce. Williams was surprised how susceptible her students were to messaging around “what is proper, what is presentable, who gets to decide.”

For Williams and her students, her deviation from the original lesson plan became an opportunity to illustrate how the course’s significance transcended arbitrary facts and grades. In Williams’s classroom, the course served to bridge the sometimes wide divide between the student and the individual.

Though teachers had various interpretations of the course, they shared recognition of its value.

Boroski described this class as an opportunity to promote interest in educational careers, saying, “We want to push more of our students to become teachers.” Boroski highlighted the importance of representative curricula and teaching, considering he is positioned as a white educator in a predominantly non-white community. “This course can be a unifier if done correctly.”

While Williams had apprehensions about having a “real” history course being situated outside of the popular U.S. History curriculum, she approved of what was available. “If they’re not going to completely rewrite and review the U.S. History curriculum,” she said, “then yes, this course does do well to stand alone.”

To Williams, though the course itself leaves room for improvement, it represents something invaluable. “I think this course in particular hopefully allows students to connect to not just content in a more authentic way but really see we’ve all contributed something to make this nation what it is. There’s good and bad and ugly everywhere, but there’s so much value in being able to explore these things together.”

“The mere existence of this sends a message,” Williams said, “that it is important, that it matters, that it is U.S. History.” Connecticut’s students and teachers are the proof.

— Chloe Nguyen is a sophomore in Saybrook College and an Associate Editor of The New Journal.

Photography by Ellie Park and Chloe Nguyen.

*An earlier version of this article misspelled the last name of Ryan Boroski. It is “Boroski,” not “Borowski.“

*An earlier version of this article misstated the last initial of Drew W. It is “W,” not “S.“