Yale’s Club Skeet & Trap team garners attention from admitted students, alumni—and gun lobbyists.

The imperative of skeet and trap is simple: shoot at moving objects in midair. Hit as many of them as possible.

At a small red-brown clubhouse in East Lyme, CT—45 minutes from New Haven—12 Yale students fire away.

Their targets are clays, 4-inch wide orange discs, shot out from an oscillating “bunker” machine. When hit, the clays fissure in a dramatic transformation from solid rounds to shards and dust. Their remains descend onto the field like terracotta snow.

Every shot emits a sonorous pop—imagine the world’s biggest champagne cork coming loose from its bottleneck. But the members of Yale’s club skeet and trap team are used to this: they do it every week.

With more than 100 years of history, a clubhouse of its own, and a committed (if small) roster of athletes, the Yale Club Skeet & Trap Team is a powerhouse in the world of college shotgun sports. Yet, few students at Yale even know it exists.

On a national level, clay target shooting plays a significant role in conversations about firearm use. From some vantage points, it represents a middle road in fights over gun ownership, demonstrating the possibility that guns can fit safely and uncontroversially into the fabric of daily life. But a broad view of the sport, its funding, and the culture surrounding it presents a more complex picture.

***

Skeet and trap are separate but similar events. In skeet, two bunkers fire clays which cross somewhat predictably in midair. In trap, a single bunker fires clays at random angles, requiring quick reflexes.

Trap’s existence precedes skeet’s by over a century. The first known mention of a trap-like sport is from 1793 in Volume 1 of an English periodical called Sporting Magazine. In it, an article describes the emergence of an activity involving placing live pigeons in a small box—a “trap”—with a sliding lid. The trap was lowered into the ground, and on the cue of a shooter, its door was drawn open, releasing a bird into the line of fire. It was “the most infatuating and expensive amusement the juvenile sportsman [could] possibly engage in.”

Clay pigeons replaced live ones when the sport crossed the Atlantic in the early 19th century, and the cruelty-free version of the sport became a popular American pastime. Americans shoot skeet and trap competitively from the middle school level to the Olympics.

In both skeet and trap, guns are unloaded with a “break action”—snapping them open at a central hinge to eject old cartridges and insert new shells. It’s this mechanism that distinguishes them from semi-automatic weapons, which don’t require intervention to reload.

The sport has widespread and surprisingly bipartisan appeal, even for politicians who push for gun control. Throughout his 2024 vice presidential bid, Minnesota Governor Tim Walz has repeatedly boasted about having been “the best mark in Congress.”

In 2013, President Barack Obama announced that he’d picked up skeet shooting as a hobby during his time at Camp David, the presidential retreat. Accompanying courtesy photos showed POTUS in wraparound sunglasses, his cheek flush to the comb of a wood-paneled shotgun.

This announcement came when the former president worked to ban assault rifles and high-capacity magazines, as part of an intensified gun control push following the 2012 murder of twenty students and six adults at Sandy Hook Elementary School.

President Obama told The New Republic that he was speaking publicly about his hobby to bridge gaps between Americans with a variety of attitudes and experiences towards guns. “Advocates of gun control have to do a little more listening,” he said.

The gun lobby, however, was not impressed with the President’s attempt at listening.

“In his effort to pursue a political agenda, he apparently is willing to convince gun owners that he’s one of us,” NRA lobbyist Chris Cox told the New York Times in response to the image. “Skeet shooting…doesn’t make you a defender of the Second Amendment.”

***

The inaugural Yale shooting competition was against Harvard in 1888. Yale won. Newspaper records suggest that they continued to dominate for years after.

Today, the team is small but mighty. It is the only active Ivy League shooting team, and one of few teams in the Northeast to have been continuously active for over a century. At many schools, teams have dwindled or gone extinct. The Harvard Shooting Club has been repeatedly abandoned and revived. Presently, it does not exist.

Much of the Yale team’s fortitude can be traced back to Ed Migdalski, the father of the team’s current coach, Tom Migdalski. Ed was the skeet and trap coach in the 1960s when he began raising funds to establish the Yale Outdoor Education Center, which emphasized the sports of fishing, hiking, and clay shooting.

The University footed part of the bill to establish the Center, and donors paid the remainder. The skeet and trap fields were built on a small offshoot of the property where the gunmen’s clubhouse sits, a cozy space with a taxidermied moose head on the interior wall.

In 1984, Ed handed off the reins of the skeet and trap team to his son, Tom, who now runs all of Yale’s club athletics programs. Tom quite literally wrote the book on skeet and trap. His instructional manual, The Complete Book of Shotgunning Games, sells on Amazon for $19.95. The Migdalski name is all but synonymous with skeet and trap—and with Yale club sports at large.

When asked about succeeding Ed as Yale’s coach, Tom responded: “Any collegiate club team of any sport needs engaged leadership that spans year to year for continuity and success.” He believed this was especially true for a sport as “logistically complicated” as skeet and trap. “We were simply lucky that I followed my father in this role,” he added.

At Yale’s 2023 extracurricular bazaar, the skeet and trap table was set up in full glory. A tri-fold poster featured photos of the team’s 13 members hanging out at their clubhouse in East Lyme, CT—making finger guns, high-fiving the camera with red plastic cartridge cases on their fingers, and walking back from a long day of shooting with their rifles slung over their shoulders.

“It’s like my therapy every week,” said Linton Roberts ’24, a 2023-24 co-captain of Yale Club Skeet & Trap hailing from Gadsden, Alabama. “You just let it go for an entire afternoon.”

Roberts joined the team in the fall of 2019, at the beginning of his freshman year. Like many, he’d found the early weeks of college challenging and was suffering from homesickness. “To be frank, there were only six kids that came up here from Alabama, and I didn’t know any of them,” he said. “I was looking for stuff that I was familiar with.”

Roberts had never shot skeet or trap before, but he’d grown up hunting with his family and had his own shotgun—which he’d left behind in the move to New Haven.

“To my surprise, Yale had this team,” said Roberts. “I was just like, Oh my gosh, sign me up.”

Roberts began attending weekly practices at the team’s private off-campus facility. He looked forward to regional competitions at nearby military academies, the annual trip to college nationals in Texas, and the chance to enjoy some leisurely time far from the bustle of the city.

The team prides itself on having a diverse range of student members. Athletes do all sorts of things when they’re not shooting—they are engineers, comedians, frat brothers, and musicians.

Demographically, however, the team is more homogenous. In the 2023-24 school year, all 13 members were white. Only 4 were female.

These numbers do align fairly well with national trends in gun use and ownership, according to Pew. 49 percent of white Americans have a gun in their household, as opposed to 34 percent of Black Americans, 28 percent of Hispanic Americans, and 18 percent of Asian Americans.

As for gender, 40 percent of men personally own a gun, and only 25 percent of women do.

Anna Oehlerking ’25 came to Yale fully aware of the existence of Yale’s skeet and trap team; it stood out among its Northeastern competitors for its longevity and size. “It was why I chose to come here,” she said. “Well, that and they had an environmental engineering major.”

Oehlerking grew up in a neighborhood where “everybody had a gun safe in their basement” and had competed on her high school skeet and trap team in Minnesota (a major shooting sports hub) prior to coming to Yale. Having a “tie back home” through shooting sports helps her “stay grounded,” she said.

When Oehlerking joined the team in August, she brought her gun in tow. Several members of Yale Club Skeet & Trap shoot with their own firearms, though both driving with and shipping a firearm are bureaucratic headaches.

Boosters of shotgun sports (especially male ones) often comment on the fact that events like skeet and trap offer a rare opportunity for women to compete on equal ground with men, even if fewer women participate.

“There are girls on the team that weigh probably half as much as me, and they can outshoot me any day of the week,” Roberts said. “That stings a little bit.”

These repeated assertions of gender parity seem to respond to an unspoken association between guns and masculinity. Empirically, more men own guns than women, and among people who do own guns, men are more likely to carry them, and to own more than one. Popular iconography is replete with images of men with firearms—G.I. Joes and their machine guns, cowboys with pistols in their holsters, school shooters-to-be ordering bump stocks online.

Oehlerking, meanwhile, is a self-proclaimed “very liberal Democrat,” a vegetarian, and a pacifist. As a girl who shoots for sport, she wishes she could shed the association between rifles and senseless violence.

“People associate recreational shotgun shooting with a lot of negative things,” she said. “All that stuff is terrible, [but] I don’t think it really has anything to do with the sport.”

***

Skeet and trap are also expensive.

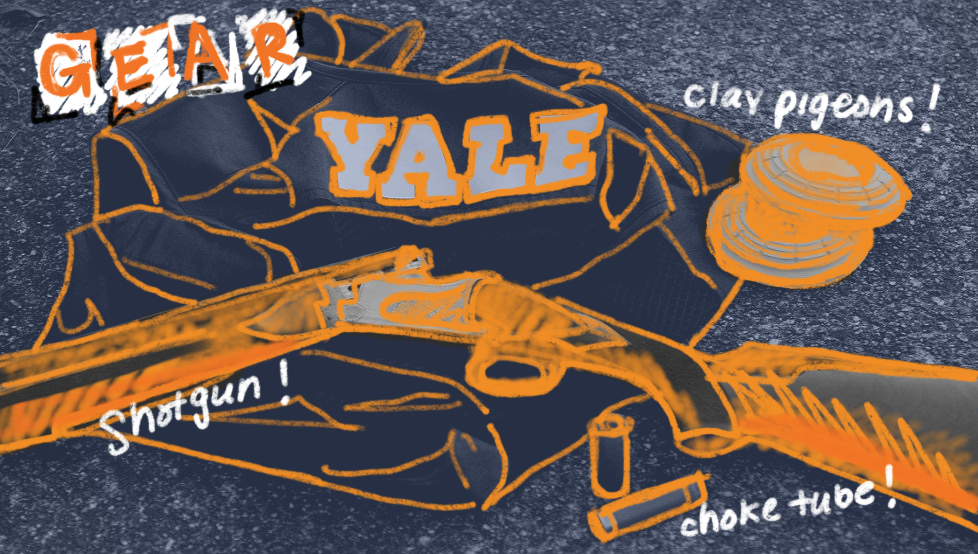

With each marksman using 100 shells per practice, which costs around $40 per person, the estimated annual cost of ammunition for a single practice with everyone in attendance is $520. If the team has 10 practices in a semester, the cost soars past $5,000. Then, there’s the price of transportation, food, and team gear, and the maintenance of the guns and the clubhouse where they’re stored.

Some of that money comes from member dues, numbering several hundred dollars per semester. Additional funding comes from the Yale club sports budget, though likely not enough to sustain the team. Donations to the team are an integral part of its financing. Some of these come from alumni, who receive solicitations from the team several times a year. But the forces keeping Yale Club Skeet & Trap alive extend further than the Yale network.

National advocacy organizations and philanthropic groups funnel millions of dollars into high school and college clay teams each year. Some of these organizations are directly connected to the gun lobby—legislative groups committed to blocking bills for universal background checks and the limiting of AR-15 purchases.

In 2009, the National Shooting Sports Foundation, a “firearm industry trade association,” launched its Collegiate Sporting Initiative to expand recreational and competitive target shooting across the country.

The NSSF—run by Stephen Sanetti, who is the former chief executive of gun manufacturer Sturm, Ruger & Co.—also runs the nation’s largest gun show, the SHOT expo, and lobbies against gun control legislation.

The NSSF has sent at least $20,000 of grant money to Yale’s team. Yale banned donations from the NSSF in 2013, as part of a broader ban on accepting money from business lobbying groups in order to eliminate laborious vetting processes.

Yet, Yale continues to receive money from the MidwayUSA Foundation.

A 501(c)(3) with $273 million in assets, the MidwayUSA Foundation is run by the Potterfield family—whose fortune comes from running a private company that sells guns and related gear online. The foundation helps skeet and trap teams raise money by providing a digital platform and organizing free fundraising events. When a team supported by the MidwayUSA Foundation raises money, it goes into an endowment account. Larry and Brenda Potterfield match it dollar-for-dollar.

“We help those who help themselves,” said Jay McClatchey, a representative from MidwayUSA.

The difference between the MidwayUSA Foundation and NSSF is that MidwayUSA’s sole organizational focus is shooting sports. A search for Yale in the foundation’s “find-a-team” directory turns up an endowment listing for The Yale University Shotgun Club, managed by Tom Migdalski. According to the site, Yale’s team has an endowment balance of over $168,000—17 percent of its listed goal of $1 million.

“We don’t advocate either way, from a political perspective,” McClatchey said of MidwayUSA. But this statement is only true in the strict domain of the MidwayUSA Foundation.

Privately, the Potterfields are major supporters of the National Rifle Association—the nation’s largest pro-gun lobby, whose legislative arm stands in wholesale opposition to checks on gun ownership and use. Brenda Potterfield was a board member for decades, and in January of 2024, the Potterfields were named by a consortium of NRA-run shooting and hunting publications as the inaugural recipients of the 2024 Golden America’s 1st Freedom Award.

The Potterfields’ firearm-selling company, MidwayUSA, is an explicit supporter of the National Rifle Association as well. “No company in America is more dedicated to and more supportive of the goals of the National Rifle Association than MidwayUSA,” says the firm’s website, which also offers an NRA donation round-up program for online purchases.

***

Like all sports, riflery is satisfying. “I remember the first time I shot a perfect 25-straight targets,” said Robert Person, GRD ’11, a team alum and former assistant coach who now runs the skeet and trap team at West Point. “It’s an awesome feeling.”

Of all the sports that deliver this rush of pride, skeet and trap are actually among the less dangerous. Football, rugby, and MMA produce far more injuries. Most sports, in fact, involve a choreography that either simulates or enacts violence—thwacking and tackling, hurling and hitting. In many sports, an attempt to score a point is called “shooting.”

But skeet and trap is not like other Yale sports. A basketball team does not burn through $520 worth of basketballs in a single practice. A lacrosse team does not keep its sticks in an offsite safe. A swim team does not need to decide if it will accept money from lobbying organizations.

Skeet and trap is among the safer sports, and yet, holding a shotgun feels nothing like holding, say, a baseball bat. A shotgun is twice as heavy, freighting its carrier with a sense of responsibility. Everything must be done right—the opening and closing of the safety, the angle at which the gun is loaded and unloaded. The kickback bounces through the shooter’s entire body. The sound is loud enough to require headphones.

In another context, or even fired in another direction, a gun has a lethal power no baseball bat will ever have.

“Let’s face it,” said McClatchey. “Shooting is a political hot potato. A lot of institutions, especially collegiate ones, have divested themselves of shooting teams.”

It’s easy to imagine that Yale might follow suit.

And as long as gun lobbying organizations powered by the likes of the Potterfields are funding shotgun sports, keeping guns in skeet and trap fields may also mean benefiting from the effort to keep guns everywhere.

For members of Yale’s team, this broader backdrop is difficult to escape. When Oehlerking tells Yale classmates about her passion for shooting sports, “they’re taken aback.” In her early days at Yale, these negative responses thrust her into a “moral dilemma,” she shared.

She resolved this personally by viewing skeet and trap as existing on its own little island—the remote idyll of the East Lyme Clubhouse.

“It’s locked away,” she said. “And I’m glad for that.”

– Abigial Sylvor Greenberg is a senior in Pierson College.

Photos courtesy of Abigail Sylvor Greenberg. Illustrations by Sarah Feng.