The residents of a psychiatric care village create art and fellowship.

Sandwiched between houses just past Brick Oven Pizza, Fellowship Place resembles a drive-through window: a canopy shades the front desk, and glass walls allow its bustling energy to seep out onto the street. Behind its front gate sit scattered maple-colored buildings, separated by benches and grass patches.

“Four years ago, my mental illness reached a critical level,” John* said. We sat in a paint-splattered arts studio in one of Fellowship’s buildings. “I was barely fit to be in public.”

A silence followed, but not an awkward one—the room held no hesitancy toward emotional depth. His palms, tucked under his thighs, squeezed and shifted in his chair.

John, 60, was born in Branford, Connecticut. In 1989, he was diagnosed with bipolar I with psychotic features, soon followed by diagnoses of generalized anxiety disorder and complex post-traumatic stress disorder. He describes his mental illnesses as a series of “cascading traumas”—each condition, left untreated, spiraled into the next.

In 1990, John began psychiatric treatment for his illnesses at a behavioral healthcare agency in Branford, where he received treatment for over thirty years. He recalls the experience with little fondness—his clinicians, “hostile and unhelpful,” would respond to his specific requests by thumbing sticky notes to their computers, claiming they’d eventually “get to it.”

Three years ago, John hit a wall in his psychiatric progress. Without emotional and social support, his mental health destabilized. Looking for community, he thought of Fellowship Place, an organization referred to him by a friend years prior.

“I knew it was where I needed to be to get the kind of support I needed in order to recover,” John explained. “And that’s what happened.”

In 1960, Phyllis McDowell—educated in psychology at Sarah Lawrence College and involved in many of New Haven’s mental health organizations—founded Fellowship Place amid the deinstitutionalization movement, when long-stay psychiatric hospitals were being shut down and replaced with community-oriented mental health services. During this awkward transition stage, Fellowship functioned as a weekly drop-in social program for people with mental illnesses, offering weekly dance classes paired with refreshments, music, and socialization.

It’s since kept with tradition. Mary Guerrera, Fellowship’s executive director, describes Fellowship today as a “one-stop shop” for mental health—an all-in-one supplement to psychiatric care, focused on community-building. Fellowship is staffed by forty-five employees and supported by volunteers, many of whom are licensed clinical social workers or are otherwise experienced in supportive services.

Fellowship’s mission of social support is anchored by its physical community. Fellowship owns four affordable-housing apartment buildings—three on Fellowship’s main campus and one in West Hills—with rent offered at a rate of 30 percent of residents’ incomes. Residents with no income receive free housing.

“Lack of daily structure and social connection is a big challenge for people with mental illnesses,” Guerrera said. Current psychological research indicates that mental illness and social connectedness are cyclically related: social support is a central component of recovery from serious mental illnesses, but many mental illnesses cause people to disconnect and isolate from their communities, inhibiting them from effective recovery.

To address this cycle, Fellowship Place offers the Psychosocial Rehabilitation Service, affectionately known as the Clubhouse.

The Clubhouse offers community service events, recreational outings, fitness classes, counseling services, and cultural events to over three hundred clients. Most unique of the Clubhouse’s offerings, perhaps, is the Expressive Arts Program. It offers therapeutic services fueled by artistic expression: dance classes, music groups, and visual arts classes.

“It’s a beautiful blend between art and psychology,” explained Marisabel Sanchez, a New Haven artist and Fellowship’s Expressive Arts Coordinator. “Typical cognitive-based therapy is about thinking about your issues in a different way; it’s about changing your perspective on the issue you’re facing. Art is similar, but more expressive.”

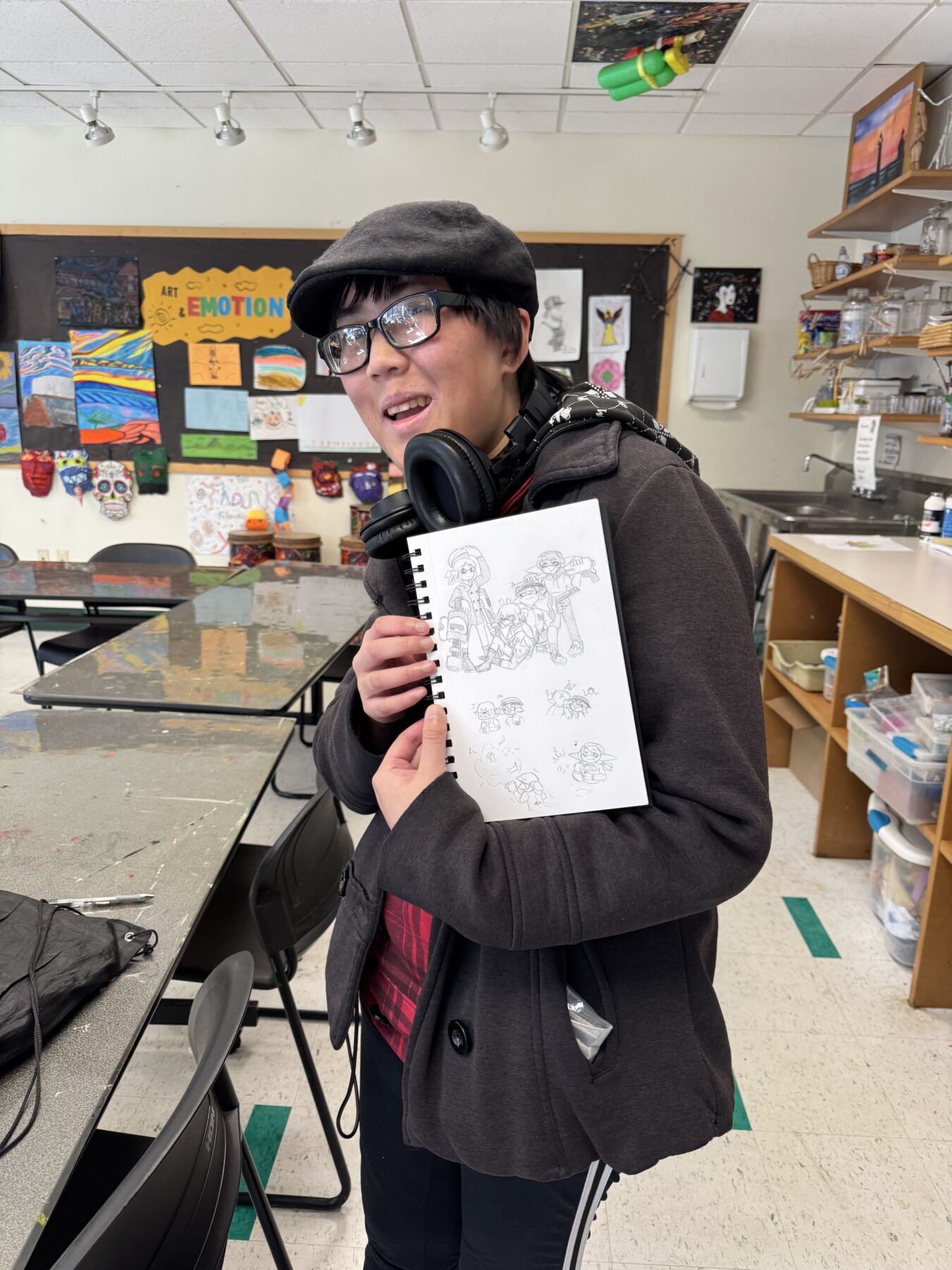

Leo Trang, the first Fellowship client to join Sanchez and I in the Clubhouse, agreed. Hefty black headphones sat around his neck, the wire looped repeatedly around the front strap of the brown satchel slung over his shoulder.

He spoke with his hands. “I have a range of emotions from, like, here to here.” He created a spectrum with his palms parallel to the ground, one above his head and the other at his chest. “Before coming to Fellowship, my mood was always low, and the medicine could kind of push me up to a normal level.” He moved his bottom hand up to his chin. “But the medicine locks you into that point.”

Trang was the first person at his psychiatrist’s office to ever successfully stop taking medication, which he attributes entirely to Fellowship. Before Fellowship, he tried traditional therapy, group therapy, intensive outpatient programs, and a different art program—all to no avail. Fellowship’s community nurtured his wellness in a way that no other form of mental healthcare could.

Trang attributed Fellowship’s unique effectiveness to the autonomy it affords its clients. “We’re not just people lumped in here—there’s no bell telling us to move from class to class,” he said. “We’re all actually hanging out together. We’re socializing of our own free will.” This autonomy, he continued, allowed him to build a genuine community that motivated him to visit Fellowship consistently.

Charlotte Sabovic, a licensed clinical social worker and the director of the Clubhouse, explained that this autonomy is foundational to Fellowship’s healthcare strategy. “Too much of their lives is so prescribed,” Sabovic said. “They’ve been told what to do for whatever amount of time by too many different people. In here, it’s not that at all.”

Trang burst out in agreement: “We can actually breathe.”

Sabovic stifled a smile before continuing. “It’s a person-centered approach,” she said. “We’re here to encourage them. It’s led by what they want to do, independently.”

To John, for example, Fellowship largely serves as a middle-man between him and the resources he needs.

John has been heavily involved in the New Haven arts scene since moving here in 1997, and Fellowship brought him a community with which his art could grow. In his experimental pieces, he explores the relationship between photography, paper, and light—he creates automatistic pieces, which are intended to be interpreted distinctly by each viewer.

Through his art, John retroactively observes his mental health. “I can look back at my work and think, ‘Oh, jeez—that’s what I was feeling.’”

This self-awareness provided him the mental stability to pursue the psychiatric care he needed. After working with Fellowship for months, he transferred his psychiatric services to a new provider, where he received medication that further stabilized his mental health.

When asked about the future of Fellowship Place, Guerrera emphasized the importance of strengthening Fellowship’s physical community. “All I want is the dollars to build more housing,” she said. “Some of these people don’t have incomes. The solution to this problem isn’t just affordable housing. We need deeply affordable housing, and we need support services.”

With its rent accommodating for residents’ incomes, its community-based support system, and its case management resources, Fellowship seeks to fill this need.

— Keertan Venkatesh is a first-year in Saybrook College.

*John is a pseudonym to protect the individual’s privacy.