*Content warning: this piece contains description of self-harm

My combat boots were still flecked with dirt and my forest-green fatigues were covered in mud and sweat. Somehow, my beret sustained its creases despite soaking up the bits of camouflage face paint that I hadn’t managed to properly wash off. The city was dead quiet. It was 3 a.m., my phone was out of battery, and I had to walk home from the hospital.

My nineteen-year-old recruit, Bing Jie, was hooked up to an IV and probably fast asleep. Two months ago at this time, he probably would’ve been at home, awake maybe, playing video games, watching TV. At the time when he first enlisted, he told me, he was a professional League of Legends player. He had come fourth in a national competition the year before. In terms of national service, he really wanted to serve in the cyber security division. Instead, he was tossed into infantry, and he came under my charge. Rhabdomyolysis had broken down his major muscles. Now, he couldn’t walk without excruciating pain in both legs. The moment when he had collapsed into a messy heap of limbs and grass, he couldn’t even call out for help.

While we were in the waiting room, Bing Jie’s dad and older brother arrived. After a terse conversation with me, they sat with him on the other side of the room, away from me. They tried their best not to talk to me directly, and neither of them used my name. I was “sergeant,” a tool of the state’s military apparatus.

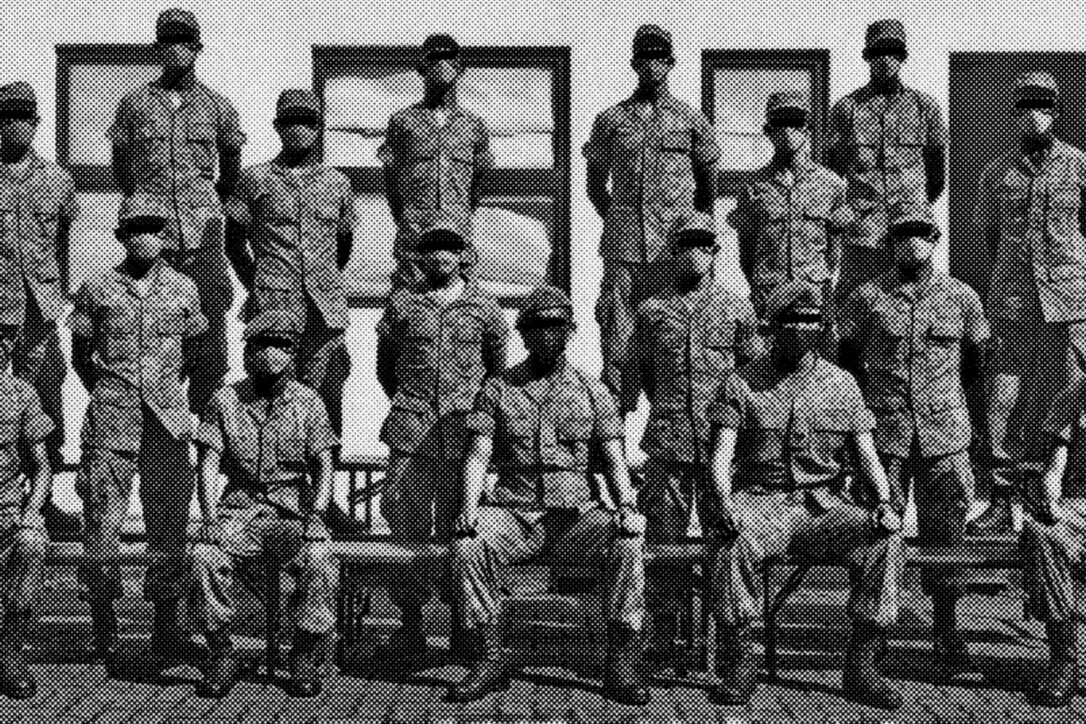

Basic Military Training (BMT) is a milestone in the lives of all Singaporean men. It marks their mandatory enlistment into the Singapore Armed Forces (SAF). The training center isn’t even on the mainland; boys are packed onto ferries and shipped to Pulau Tekong, an island right off the coast of Singapore. It’s where their identification cards are exchanged, and suddenly they are no longer “citizens” but “NSF” (Full-time National Servicemen). It’s where the SAF shaves the boys’ heads and the tropical sun burns their scalps. It’s where they fire their first rifle, where they dig their first trench, and where they start the endless cycle of physical and strategic combat training. After two months of grueling regimentation, recruits graduate and are then assigned to military vocations. The top 20 percent of recruits are sent to command school to undergo further combat training, Officer Cadet School (OCS) to become an officer, or Specialist Cadet School (SCS) to become a sergeant. But BMT is the start of any military career. Its motto: “Where boys become men.”

I entered BMT as an 18-year-old, having gone to high school in the United Kingdom and therefore largely unfamiliar with Singaporean society. National Service had always been something I dreaded. All throughout high school I had been bullied by other boys, who called me a “faggot” and kicked me when teachers weren’t looking. I was often reduced to tears, made to feel unfathomably small, and helplessly alone. If high school was like that, I couldn’t imagine what the army would be like. I considered myself a progressive, I thought militaries shouldn’t exist, and I knew my queerness was not accepted. I made the conscious choice to remain closetedI enlisted with the bold assumption that the army was not going to change me or my beliefs. But to avoid being criticized or belittled, I tried my best to excel in this performance of masculinity.

I did well. My athleticism translated well to military training. I accepted the torrent of insults and verbal abuses my sergeants hurled at me. And when I was commended for my abilities, a part of me truly enjoyed it. For the first time in my life, I was considered tough and strong. I completed BMT fifth in my platoon of sixty-four, and I earned a position in SCS. A week later, I started my training to become a sergeant and a commander.

In SCS, I spent six months learning more advanced forms of combat and familiarizing myself with a diverse array of weapons, from machine guns to RPGs. I navigated miles of dense vegetation while carrying a seventy-pound field pack. I survived in the jungle for nine days without any contact with the outside world. With the completion of each exercise, the joy I found in the military became more real. I enjoyed infantry training in a way that would have been entirely alien less than a year before, intoxicated with my adaptation to an ideal masculinity. When I graduated, I was assigned to be a BMT trainer. Upon receiving my posting order, I promised myself I would be different, patient. “Be the change you want to see” was what I kept repeating to myself.

It was an unending cycle of vicious masculinity: violence begetting more violence.

I remember the first time I made another person cry. He was part of the first batch of recruits I ever trained. In the first few weeks of their training, the recruits are given snacks to eat at night, as a part of their grace period: packaged buns, stuffed with artificially flavored cream the color and texture of playdough. The buns tasted like nothing but sugar, which was pure heaven compared to the nauseating food that we ate at the cookhouse. I’d had a rough day—contrary to my expectations, being a trainer was not simple and I was growing more and more frustrated with how ineffective I felt. My strategy of patience seemed completely inept compared to the fear other commanders were able to strike into their recruits. As much as I wanted to be morally strong, I felt myself becoming alienated. I was barely sleeping, and I hardly had time to eat. So, when I caught a glimpse of a recruit running out of his bunk to grab an extra bun from the parade square after lights out, I lost it. What came out was closer to barking than yelling, and it echoed so loudly that some heads peeked out from the fifth floor. “What the fuck do you think you’re doing?” He dropped the bun instantly, keeping his head down as I unleashed my wild wrath on him. As he walked away, I realized the blotches on his shirt were not sweat marks, but tears. When I reentered the company office, my friends and fellow commanders dapped me up. Later, my captain pulled me aside and commended me for enforcing discipline. As I went back to my bunk, I smiled for the first time in a while,

Bing Jie was in my third and final batch of recruits. By then, I had grown into a “seasoned” trainer. I had learnt to harness my unbridled fury on my recruits, breaking them down physically and mentally into passive bodies, moldable soldiers. My rage was a defense mechanism, a way to throw others off my trail. If I could be “tough” and harsh on my recruits, no one could, not even the boys from high school, could call me a “faggot” anymore. Before enlistment, a batch is given a grade based on their expected physical and mental competency. My first two batches had been A’s; Bing Jie’s was a C, and I felt the difference immediately. No matter how hard I pushed, they couldn’t meet my timings. They were consistently late, none of them could perform any marching drills in sync, some couldn’t even hold up a rifle without shaking from the effort. It was a combination of physical inability and mental disinterest. But I had to be the one that got them there.

The Combat Circuit is BMT’s most difficult physical training. It requires recruits to dress in full battalion order, including field packs, suffocating armored vests, and heavy helmets. Then, they’re thrown into an outdoor training ground, made to climb steep hills, dash from tree to tree, and crawl through thick mud. The exercise is supposed to simulate the motions of jungle warfare. When I was a recruit, our sergeant shouted insults at us as we did the circuit, and I did the same to my recruits. Nothing was off limits. I was telling them how worthless they were as they scrambled about, their rifles swinging wildly by their neck, knocking into their chins. Suddenly someone shouted out in alarm. Bing Jie had disintegrated into a crumpled heap underneath his field pack, which was larger than him. I thought he was faking it. Three hours later, after the medical staff had evaluated he needed to be sent to a hospital, I volunteered to go.

My commanding officer gave me the next few days off, and my house wasn’t far from the hospital. Under moonlight, the quiet roads felt like burgeoning gulfs. I reached into my pocket to find a crushed pack of Marlboro Reds for a smoke, a habit I had picked up in SCS, but I couldn’t find my lighter. Somewhere along the way, a car drove past me, its headlights illuminating my dirty silhouette against an empty shopping mall. At the sight of me, the driver was startled. I felt like a ghost from the jungle, a savage specter haunting the city. About a mile from my house, I passed by the twenty-four-hour McDonalds that I used to beg my mum to take me to when I was a kid. A group of drunk teenage boys was there, trying to scale the attached playground. I was reminded of combat obstacle courses. In a couple years at most, they too would be starting BMT, like I had, like Bing Jie did, like all of us would. It was an unending cycle of vicious masculinity: violence begetting more violence. Staring at them, I felt a shuddering discomfort. I averted my eyes and walked home.

In the next two months, I graduated from the military and arrived at Yale. On my first night out in New Haven, my combat boots soaked up sticky concoctions of beer, vodka, and fruit mixers instead of the squelching dirt, dead leaves, and rifle shells of the jungle floor. As I danced in the middle of the sloshing crowd, a group of men snaked their way in, bluntly pushing through me. A couple months prior, I would’ve shoved back, maybe more. But, something had shifted since that night walk. To protect myself, I had adopted the violent tools of those before me, leaving Bing Jie in the hospital. Performing masculinity had not caused more harm. So I simply stared at them, not wanting to engage anymore.

I thought that I’d find solace in queer spaces, because it was the first time I could be so open about my own queerness. At an Office of LGBTQ Resources mixer, I was handed a nametag. “What do I write here?” I asked someone. “Your pronouns!” they answered. I tentatively put down “he/him,” unsure if it was who I wanted to be anymore, but equally terrified of the alternative. The group shared their collective trauma: the ways in which they were shunned, bullied, and derided for their difference, largely by the men in their lives. I thought about every punishment I had ever subjected my recruits to. With each anecdote getting heavier and heavier, I left early, ashamed of myself. I hadn’t said a word to anyone.

I felt helplessly alone those first few months, but I refused to ask for help. On Halloween night, while everyone around me prepared their costumes and left for parties, I laid paralyzed in my dorm. Without thinking, I grabbed a pair of scissors from my table and made around a half-dozen slashes on my forearm. Later that night, one of my suitemates called 911, and I was escorted to the psychiatric ward of Yale New Haven Hospital. While undergoing innumerable administrative, psychological, and medical procedures, what struck me the most was how easily my body fell into the monolithic category of “male.” I kept thinking about my position in the genealogy of manhood that I had known before: from the boys in school, the sergeants that trained me, and finally me to Bing Jie. I didn’t want to be a part of the lineage anymore. When I left the hospital, I walked back to my dormitory in the clear, cold New Haven morning air. The sun was the brightest thing I could see and a part of me strangely felt stable. Being a “man” was eating me alive, so I decided to stop.

In five months, I will have spent more time outside the military than in it. There is always an impulse to romanticize those times: the late night instant noodle parties, the raves we went to on our days off, the satisfying sense of exhaustion after finishing an exercise. I still miss catching crabs off the old bridge that we snuck out to when our recruits were asleep, and the genuine moments of tenderness in between smoke breaks and barking orders. That’s what I instinctively remember about all of it. But the SAF’s commands are all still there, in encrypted WhatsApp messages on my phone. When writing this piece, I spent hours sifting through them. The image of Bing Jie, unable to even crawl in that field, is still there.

Jools Fu is a sophomore in Pierson College.