“It is true that there is not enough beauty in the world.

It is also true that I am not competent to restore it.

Neither is there candor, and here I may be of some use.”

– Louise Glück, “October”

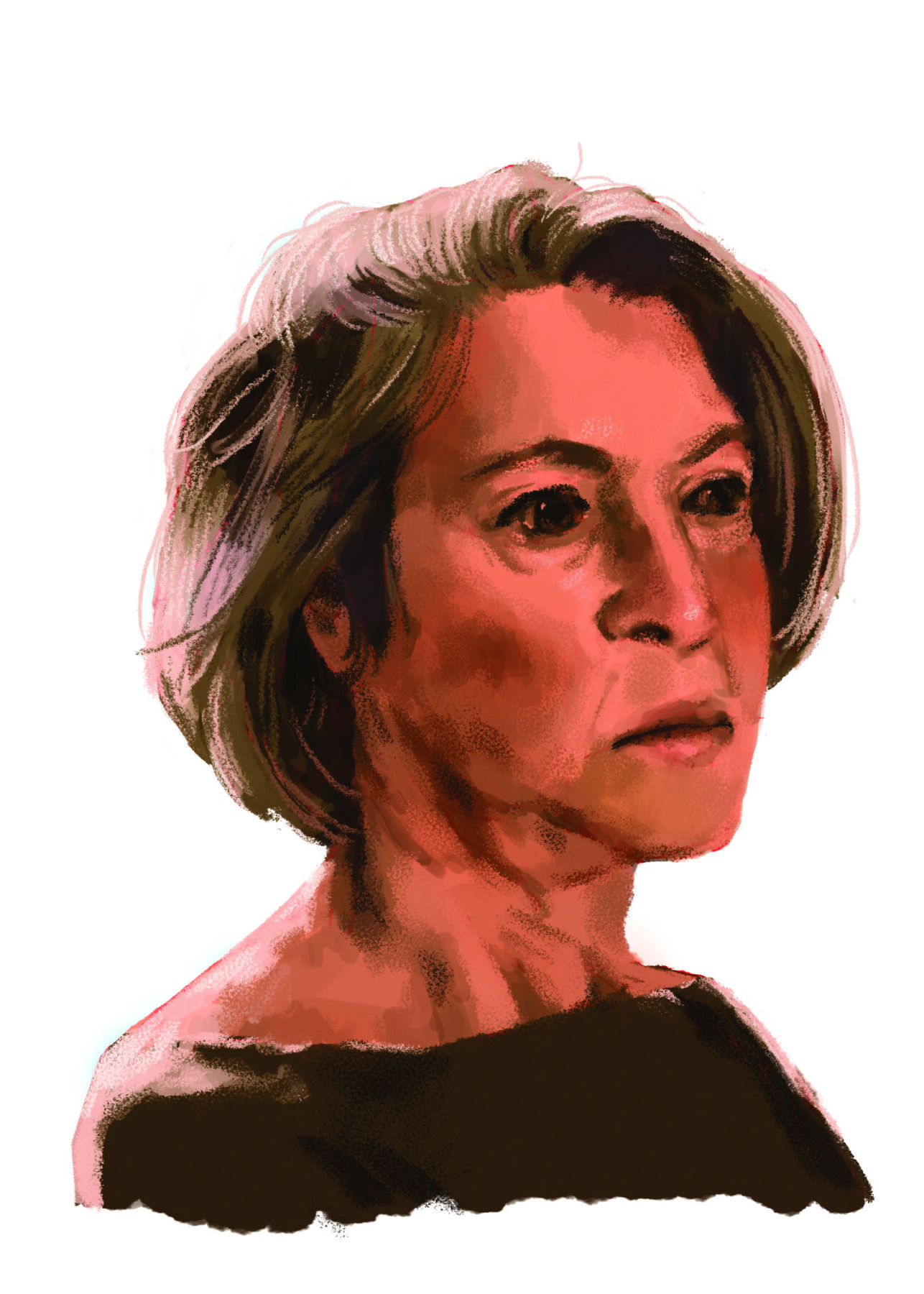

It was this very candor that characterized our first interaction. I was a freshman at the time, and a friend who was enrolled in her workshop offered to introduce us if I walked her to class early. Nervous and giddy, I followed my friend into the seminar room and approached the head of the table. My literary idol looked surprisingly casual in her scarf and navy blue coat. “It’s so nice to meet you, Professor Gloock,” I said, hastily pronouncing the last name with an exaggerated vowel, as in glucose. “You’ve been a huge inspiration for my poetry.” She looked at me and, without malice or warmth, said, “it’s pronounced Glück,” pronouncing the umlaut like the word “Buick” with the two vowels melded into one. Then she moved on with her class. Embarrassed as I felt, I was also amused that the real-life Louise Glück was just as straightforward as the one I’d encountered on the page.

I first came across Glück’s critical essays as a 16-year-old poet. At the time, I was torn between loving poetry and hating what I deemed its self-important discourse. Many American poets, seeing the general public’s disdain for their work, responded by doubling down on praise of one another’s writing, making sweeping statements about poetry’s urgency rather than demonstrating it. Glück was the first writer I found who departed from this ostentatious tone. She wrote with clear passion for poetry’s inexhaustible mystery, and at the same time diagnosed contemporary poetry’s drift toward self-obsession and fruitless abstraction, warning of the conditioned responses such tendencies evoked. Contemporary literary journals, she argued, are full of “poems in which secrets are disclosed with athletic avidity…poems at once formulaic and incoherent.” I shivered at her recognition of the precise kind of poetry I had begun to write in hope of publication. She unveiled a new vocabulary for discussing poetry: one of aesthetics, form, and tone, one that recognized how poetry existed to make the world both more clear and more strange. In a sea of poets and critics who were constantly selling the importance of this or that work, Glück’s rejection of bullshit made her the only voice I could trust.

It took me a couple years to explore Glück’s verse itself. Perhaps because I found her essays so incisive, I worried that her lines might disappoint me. They didn’t. Here, too, Glück rejected performative drama for a deliberate and distant voice, one whose authority stilled you, whose scathing irony made you listen close and allowed glimpses of vulnerable beauty to cut ever more deeply. Take “Celestial Music,” which begins, “I have a friend who still believes in heaven. / Not a stupid person, yet with all she knows, she literally talks to God.” Cruel and prosaic as Glück sounds here, she earns my trust. Having chuckled at her friend, I become receptive to her praise of this friend’s bravery, her disclosure of their shared affinity for wholeness, and the stunning ending when the two look upon a dead caterpillar and Glück writes, “It’s this stillness that we both love. / The love of form is a love of endings.”

Whenever I was skeptical of poetry and deprived of inspiration, I returned to Glück’s texts. During the pandemic, I convinced my parents to rent an Airbnb near Alabama’s Lake Smith. We sat outside, the cicadas humming all around, the host’s labrador curled up at my feet, and read Glück’s poetry. For my parents, two Eastern European emigres who’d grown up on the Russian poetic tradition, Glück’s poems, as lucid in image and thought as those of Mandelstam and Akhmatova, were among those few which resonated with them. The three of us connected in our shared marveling. After my parents went to bed, I walked out on the dock and sat there for several hours with my Kindle copy of Averno. Periodically, I set down the glowing screen to look up at the stars, listen to the water, and let the words echo. I hope she will forgive my pathos here.

Glück’s poetry seminar was offered every fall semester, but through a confluence of bad luck and trepidation at working closely with someone I admired, year after year passed without me enrolling. My first year, I was so weary of poetry that I didn’t apply; my second year, after regaining passion for poetry through Glück’s work, I was accepted into the course, but it was unexpectedly canceled; my third year, I was rejected. Only this semester did I finally enroll in the Iseman Seminar. My parents were overjoyed. I studied up on the umlaut and, thankfully, Professor Glück seemed to have forgotten about my mispronunciation of her name all those years ago.

The Louise Glück I met in the Iseman Seminar was consistent with the one I’d read—just as unpretentious and honest, just as cautious of tropes and sentimentality. As in her texts, her directness, though sometimes ruthless, garnered complete trust. Yet despite the darkness of much of her poetry, she was also surprisingly jovial. I loved how comfortably she passed aesthetic judgements with no need for explanation. “This word is off,” she would say, or “this line should be replaced with another,” identifying problems the ear understands better than the mind and trusting us to find solutions. She hated unnecessary adjectives and loved specificity, especially geographic. In one of my poems, she suggested scrapping almost every line except one which was merely a description of place: “through Cuneo, they came to Florence.” She vehemently rejected bullshit, not only poetic but also interpersonal. Despite being a Nobel laureate, she was never condescending—joking frequently with us, never insisting on decorum. She seemed to be less an instructor than a peer, seated at the same round table as the rest of us.

I won’t pretend that we became fast friends in the five weeks of class we had together, as much as I would love to indulge such a fiction. We had class in person twice, and I never made it to her in-person office hours. One afternoon, however, we discussed a couple poems of mine over the phone. I sat in my sunny dining room and typed madly in an attempt to write down her every word, her every criticism of every line, her divulgence that writing prose poetry was one of the most enthralling experiences of her life. When she made the off-handed disclosure that she liked my poems, my heart leaped. As the call was drawing to a close, there was a brief but seemingly endless silence in which I thought of asking something deeper, beyond the minutiae of my lines—about the usefulness of rhyme, about the disarming potential of prosaic language, about writing from beyond a singular I, about decoding Ashbery and understanding Oppen. There was so much I wanted to ask her that I hardly knew where to begin.

There will be time for those questions later, I decided, so why keep her now? I said, “Thank you so much, see you soon,” and she said, “See you.”

—Danya Blokh is a senior in Timothy Dwight College.