Revolution is coming, and it’s coming to New Haven.

For a member of the Revolutionary Communists of America, Hassan Foster is a mild-mannered man. Sporting a beanie and oversized blazer, he opened his notebook to a page titled “Left-wing Activism.” The 42-year-old was soft-spoken when we met for coffee, almost passing as just another armchair revolutionary. Nothing could be further from the truth.

After ten years in custody, Foster was released from the Connecticut prison system last spring. Charged with a violent crime, he claims he was pressured by self-interested public defenders into taking a plea, arbitrarily placed in solitary confinement for weeks, and beaten by guards who “looked at him as their slave.”

It was in prison, forced to make license plates, stop signs, and auditorium chairs for 75 cents per day, that he started to “wake up.”

Foster realized that the racism he’d experienced as a Black man growing up in New Haven “had something to do with capitalism”—the way he was treated in prison felt like “modern-day slavery.” He became fascinated by the Black Panthers; he’d seen the Spike Lee film Malcolm X as a child and pictured himself in the disillusioned and imprisoned young Malcolm.

Upon his discharge, Foster felt that a lot of people in his position would simply “sit down, blend in, and live a quiet life.” But he had to do something. He began volunteering at neighborhood projects, including the Connecticut Community for Addiction Recovery, where he met Eric Goodman, a 28-year-old from Vermont and founder of the RCA’s Connecticut branch.

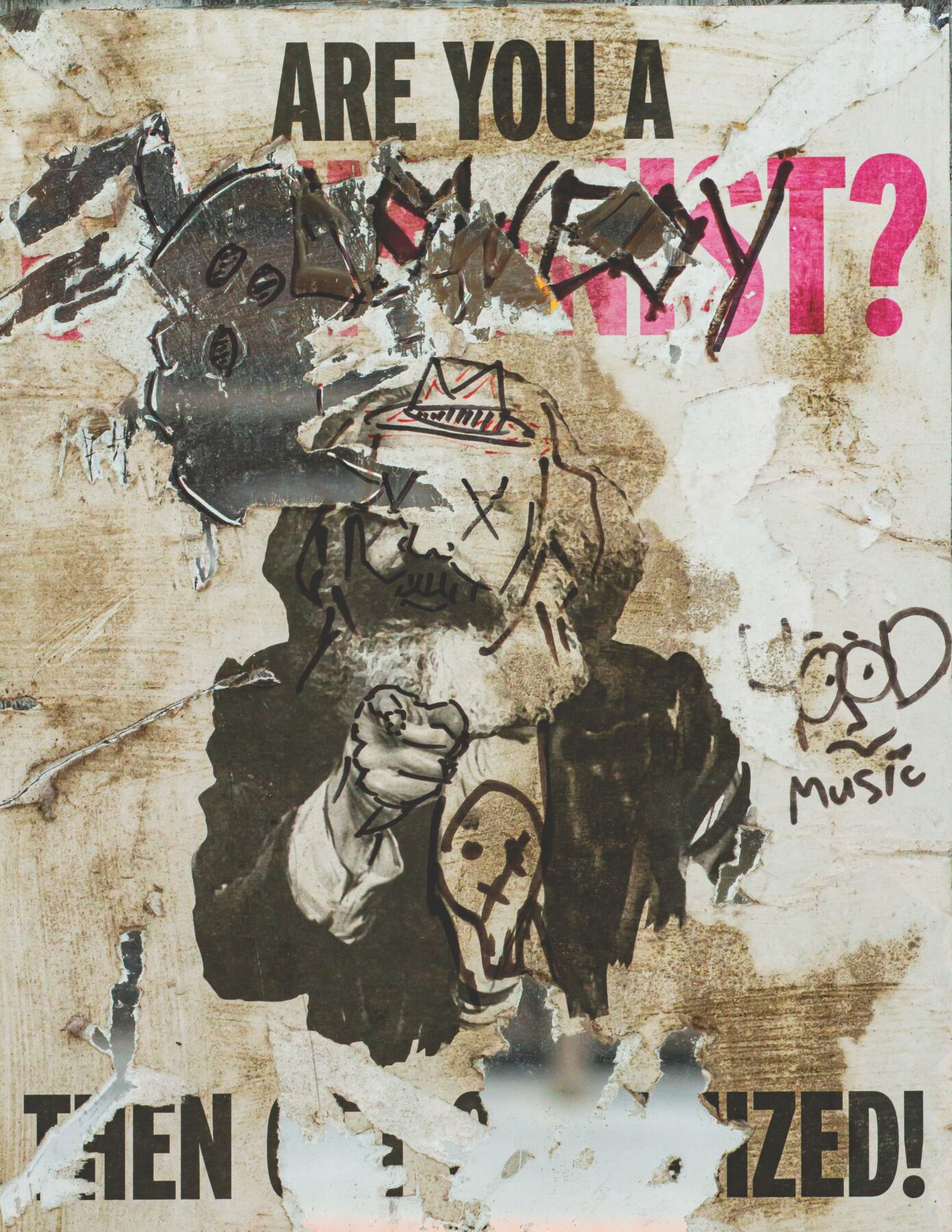

If you’ve come across the “Are You A Communist?” posters plastered around Yale’s campus, you’ve already had your first dalliance with the RCA. The group’s origins are far from New Haven: it was founded by Ted Grant, a Trotskyist who had spent the 1970s working with the insurgent group Militant to infiltrate the British Labour Party. After being kicked out in 1983, Grant started giving up on the idea that you could make change through the party system. The Revolutionary Communist International, the organization he established a decade later, had a more radical vision.

The RCA believes that under capitalism, the average person’s quality of life slowly gets worse and worse until, at some point, the floodgates break and general strikes and mass class struggle ensue. Their job is to set up a structure for the impending revolution: Goodman explained they aim to “recruit people, build up leaders, and send them back to the neighborhoods that they’re in.”

Goodman was introduced to communism as a sophomore at McGill University. At a performance art show, he was instructed to stare into a stranger’s eyes for five minutes; when their time was up, the pair began a casual conversation which soon grew political. The woman asked whether he’d want to go to a communist party meeting—Goodman tentatively said yes.

Sitting in his first RCA meeting, he found himself enthralled by how “these people were saying funny words like bourgeoise and prose…but they had a robust framework for why things were so fucked up.” His chemical engineering degree simply wasn’t part of the solution. Soon, transferring out of McGill, moving to Denver, and ditching engineering for history, he started a local branch and began organizing.

By 2020 Goodman found himself settling down with his partner in New Haven, ready to be “done with it all.” Then, the national party came calling. When a budding local communist asked the party how he could get involved with communism in New Haven, the RCA put him in touch with Goodman, impressed by the branch he’d built in Denver. Organizing, Goodman believes, “starts with two people,” and the party had found him a second.

Now, every Monday, members of the RCA get together and discuss texts—Lenin’s State and Revolution was on last week’s agenda. During the week, they put theory into practice: attending protests, holding rallies, or making the case for communism to their friends and coworkers. For now, the driving goal of the RCA is to connect like-minded people and build a network—Foster has taken college-aged “comrades” to meet his friends who are still in prison, and the group is meeting members of the New York branch this month. The RCA declined to tell me the number of members they have––either out of secrecy for their grand revolutionary plans, or the fact that they might be smaller than Goodman lets on.

Part of their strategy is to work within existing protests. During the pro-divestment protest on Beinecke Plaza last April, two RCA members camped out day and night among Yale students in an effort to translate international frustrations to issues closer to home, like workers’ rights. The RCA holds their own rallies as well, their posters emblazoned with “Fight Tuition Hikes!” or “No War With Iran!”

As Goodman put it, “Foreign policy is just an offshoot of domestic policy.”

Foster, who still isn’t quite a hardcore revolutionary, hopes the party will empower him to make changes here at home. “I’m not exactly sure what it looks like but we can do better. The country can do better,” Foster told me. He’s trying to “see a better city,” to reform the justice system, and to shine a light on the “black magic” of the courtroom. After all, while he got a second chance, not everyone does. J’Allen Jones, a friend of his, was killed in Garner Correctional Institution in Newtown, Connecticut in 2018. Foster’s tone sombered each time he mentioned his own two years spent in Garner: “It was hell in there, there was more violence than I’ve ever seen.”

Foster has found a second home in the RCA: “I’m a brother that’s been adopted into the family; they didn’t judge me for doing ten years in prison, they just invited me in. People want to hear what I have to say.” At the core, it’s a group where like-minded people from a panoply of backgrounds can gather and carve out a space for themselves. Yes, the RCA reads Lenin on Mondays, but they play Monopoly on Wednesdays and barbecue on the weekend.

However, Goodman was quick to dispel any notions that the RCA was all fun and games. “This is a hardcore organization,” he said. People have to be “up to their responsibilities”—each comrade has a defined title in the party, from ‘Secretaries’ to ‘Press Officers.’

Chantal Gibson, a 21-year-old party member from New Haven, emphatically agrees.

“Being a comrade is a different type of bond,” said Gibson. “We’re not just casual friends, and we don’t play personality politics.” The ties between comrades are based off a fundamental understanding that “when the time comes, you’re dedicated and committed to the cause.”

The RCA itself probably isn’t going to overthrow capitalism, but every Monday night, a ragtag group of activists bands together, reads Marx, and keeps a small but fierce revolutionary flame alive in New Haven. Gibson accepts that their work “may seem small in New Haven,” but for revolutions around the country and the world to succeed, “we need to do our job.”

As Goodman remarked, “A better world has to be possible—because if not, what’s the point?”

— Maximillian Peel is a sophomore in Trumbull College.