I knocked on the door of the caretaker’s office, but no one answered. I could hear a dog barking and someone shuffling around inside, but no one came to the door. I pushed it open myself and walked into a cluttered, smoky room. “Who are you?” the gray-haired caretaker asked. After I introduced myself and asked to talk to him briefly about the cemetery, he called out, “I’m busy. Have a pamphlet,” shoving one in my hand and pushing me out the door. Being so abruptly dismissed shocked me, but the Grove Street Cemetery is, in both its history and its architecture, concerned with boundaries.

The cemetery is twice removed from the world of the living—once through the existing barrier between life and death, and once through the tall surrounding wall, which now dampens the sound of passing cars and trucks. It participates in a tradition of the dislocation of death which began with the ekphora, or the secondary stage of ancient Greek funeral rites. The Greek metropolitans carried their dead outside the city to be buried, delineating the city by creating an inverse city of the dead on its outskirts. Similar motivations were behind the creation of the Grove Street Cemetery. The first town cemetery, centrally located on the New Haven Green, was sprawling, haphazardly organized, and pushed beyond its capacity by yellow fever epidemics in 1794 and 1795. In 1797, led by Senator James Hillhouse, a group of citizens successfully petitioned to move the cemetery to a new location on the edge of town, where the dead could be better separated and contained. The carefully-planned structures included wide grassy paths and square family plots.

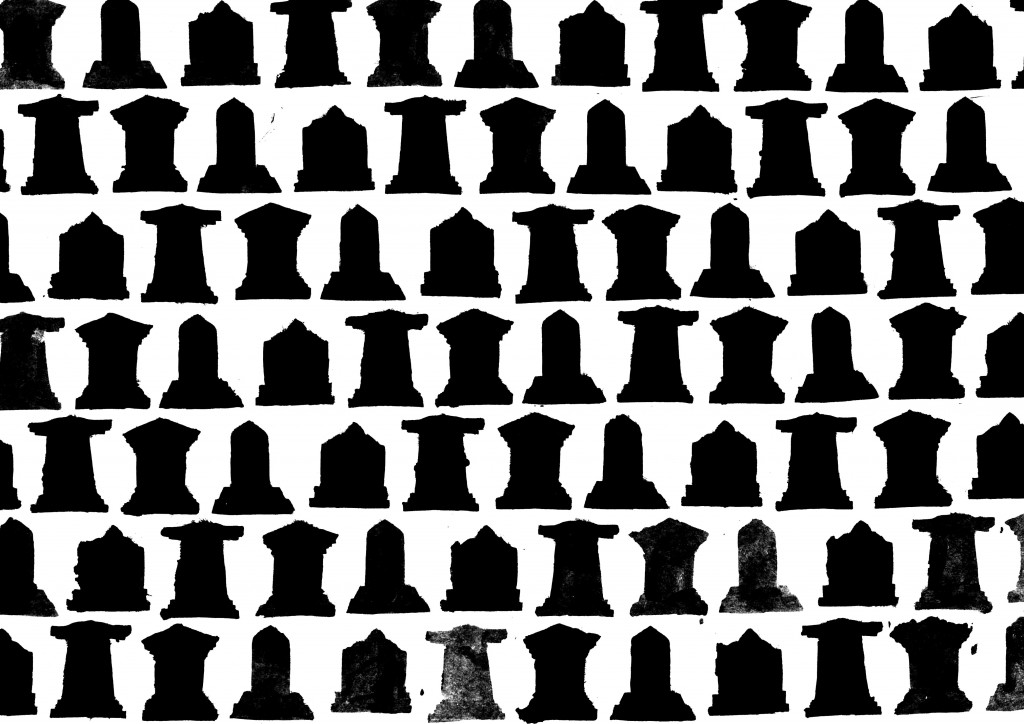

As a result of this remove, walking in the Grove Street Cemetery can be disorienting. When I first saw the street signs that mark each path, I wondered why the roads of the dead need names at all. The bevy of different architectural styles—obelisks, sculptures, bare granite blocks—I found almost too much to look at. As I walked further, however, the organization of the cemetery started to make more sense. In Greek mythology, the mapping of the underworld is never for the benefit of the dead—it is for the living, so that we may make sense of what awaits us.

The Grove Street Cemetery’s design made it a tourist attraction. By 1833, its fame was such that writer B. Edwards could claim: “And who has not heard of the beautiful cemetery of New Haven? It has been theme of more frequent praise among us than any other receptacle of the dead, save only Père la Chaise.” In this now-forgotten era, the Grove Street Cemetery was intended to serve as a public park, open to visitors and tourists and couched in a sense of spectacle and grandeur.

As its reputation grew, it became a thoroughfare for foot traffic and subject to vandalism. In response, a large wall was erected around the cemetery in 1845, funded by a group of concerned New Haven citizens. They chose to build with stone because it would be more soundproof and lasting than the cheaper wood. The enclosure was a formalized exclusion of the space of the dead from the space of the living. As I walk, these layers of removal reroute cluttered musings, and the wall’s exterior quiet results in a corresponding stillness of thought.

Whenever I’ve visited the cemetery, it has been empty. I’m not complaining—silence and solitude were the reasons I entered the cemetery in the first place. But I’ve also become fascinated by its unusual history and the stories it contains. Today, the cemetery winnows down distraction; it calls attention to simplicity. Away from the distractions of the outside world, the emptiness of the cemetery orders the chaos of my thoughts. As I walk through the cemetery, thinking about its history of distance and detachment, a similar movement of dislocation occurs in my mind. Here in the cemetery the structures of life persist, uninhabited. In the absence of other living beings, I forget about myself. In his poem “Grove Street Cemetery, New Haven,” Lee Edelman puts it perfectly: “Lost stories fill the ear’s one room/with other rooms—all empty, room on room—/while widths of sound, blown open, rise like paper.”

The strange paradox of this place concerned with removal and separation, however, is that it remains a spot of attraction for the living, a place of bringing together various pasts. It is neither a bustling tourist destination nor an empty Victorian ghost-haunt, but some combination of the two—a place where one can go to be alone and quiet, a place where one can be surrounded by a rich and far-from-silent past, or both.