No sign at The Institute Library urges visitors to keep their voices down, but there is little to tempt guests here from breaking usual reading room etiquette. The main floor is empty on a Friday in early August. Each of the oversized red chairs sits vacant in the back room of this second story library—an unlikely and unnoticeable fixture of Chapel Street’s cramped commercial row, nestled between a tattoo parlor and dated pawn shop.

An enormous oriental rug was rolled out beneath the armchairs just days earlier—an invitation, so far unheeded, to venture back into the library and find a seat around its circular central table. Closer to the front, an old wooden card catalogue welcomes visitors (once they’ve rung the library’s buzzer and climbed up the narrow staircase that leads away from the street level’s bus stop bustle). Most library card catalogues are preserved as quaint relics of the pre-digital age, but the miniature drawers at the Institute are still full—and still in use.

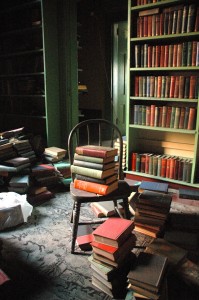

Inside, the cards document the library’s inventory (thirty thousand volumes, with more packed and stored away in bags) and history (nearly two centuries of service in downtown New Haven).

Though you might not guess it wandering among the Institute’s quiet shelves, the library has 345 current members, the most it’s had in fifty years. Rising membership is a point of pride for Will Baker, appointed the library’s new executive director in February. Just last year, the library faced near certainty of closure: buffeted by the economic crisis, the Institute’s tiny endowment seemed to be on its last legs. With only 194 members (each paying a nominal twenty-five dollar fee), the library cut its hours drastically, opening for just over ten hours a week. These days, however, Baker is hard at work bringing the bustle back to the library, where objects are meant not just to be touched, but to be used.

Baker’s timing might seem unwise. Symptoms of a print doomsday are everywhere: shuttered windows at the last-Border’s-standing, publishers struggling to deal with shifting technologies, Kindles and Nooks emerging out of purses and backpacks on the public bus. If the decline of the book is all but guaranteed, how can a tiny library like this hope to emerge from its own near-certain demise?

“If you think about libraries just as repositories of information,” says Baker, “then there is no reason for them to remain.”

The future of libraries, Baker believes, lies in their role as communities, not collections. The key to success is not keeping visitors quiet; it’s getting them talking.

…

B

Baker’s new vision is of “library as place,” a buzzword among likeminded library enthusiasts. “Too often libraries are thought about only in terms of their physical collections: the books, journals, manuscripts, and other physical materials that line the shelves,” wrote Susan Gibbons, Yale University librarian, in an e-mail. “The creation and transmission of knowledge requires conversation and debate, and libraries were designed for that purpose.”

The New Haven Free Public Library hosted over one thousand community meetings last year, and typically offers four to five programs a week at the main branch, according to Cathleen DeNigris, the library’s deputy director.

“We try to offer as many varied speakers, workshops, and film series as we can,” she wrote in an e-mail. “I believe as we enter an age of e-books and instant online information, libraries as ‘places’ become even more important. Human beings are social entities and need spaces where they can come together with others, even if they are not interacting all the time.”

It’s a vision that fits nicely in the narrative of the Institute Library’s past. From its first meeting in 1826, the Library has been as much about talking—and sharing—as it has been about reading.

In many ways, the creation of the library was unexceptional. Membership libraries, which require a small fee to make use of their collections, were unremarkable in an era that pre-dated the rise of public libraries. Likewise, the library’s pedagogical mission was also the product of a larger movement: the mobilization of the American middle class to seek out liberal arts education.

Unlike other membership libraries and intellectual societies at the time, the Young Apprentices’ Literary Association, as it was originally called, was created without a jump-start from a wealthy patron and operated without the oversight of any experienced teachers. The eight founders, all “mechanics” or “clerks” (catch-all terms for blue-collar workers), pooled their resources—most likely, several good sets of reference volumes and canonical literature—and launched a quest for self-improvement on their own. At each meeting, members were required to read aloud an original piece of writing, killing two all-important birds (composition and declamation) with one stone. Any lazy student who forgot his homework was fined ten cents.

Within a year, the founders had attracted the attention of educators and financiers willing to pitch in to support their venture. The club took the progressive step of opening its doors to women in 1835 and in 1841 was officially chartered by the state under its new name, The New Haven Young Men’s Institute (which still welcomed women). Within a decade, the library had become a bastion of inclusive and provocative discourse in the city. The intimate “seminars” of the library’s early days were replaced by a selection of three hundred classes. An ongoing lecture series featured esteemed speakers from the national Lyceum circuit, including Henry Ward Beecher, Charles Dickens, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Herman Melville.

The library’s heyday, however, was short-lived. Financial woes in the wake of the Civil War weakened the Institute, which found itself on the peripheries of the debates it had once monopolized. When the New Haven Free Public Library opened in 1886, the Institute seemed destined for obsolescence. The premise of a membership library became antiquated at best, uninviting and—ironically, given the Institute’s humbles beginnings—elitist at worst.

Under William Borden, the librarian whose hundred-year-old handwriting still fills the catalogue’s most yellowed cards, the Institute turned inward. Many of the library’s most charming idiosyncrasies are the product of Borden’s unusual stewardship from 1887 until 1910. Contrary to the lofty pedagogy of the founders, he set out to turn the Institute into what Baker calls a “laboratory for library science.” A classmate and competitor of Melvil Dewey, father of the ubiquitous Dewey Decimal System, Borden designed an alternative (and, Baker notes, “very problematic”) classification system for organizing the library’s collection. Borden’s system uses a book’s date of acquisition as part of its organizational schema, a design flaw that ultimately discouraged expanding the library’s collection. To this day, it is used in no other known library—a dead-end story that befits the library’s own declining trajectory.

…

Baker pictures a “social space” at the Institute, which he thinks will thrive if it is filled with people—not, as Borden evidently hoped, simply because it is filled with books. To be sure, Baker shares much of Borden’s bookish obsession with the library and its collection: he received a Master’s in museum studies in 2004, and worked for William and Reese, a leading rare books company based in New Haven. Yet Baker is equally committed to what he calls “community-oriented work”—an ethos of literary engagement that sets his own directorship apart from Borden’s model of custodianship. In 2009, Baker enrolled in the library science program at Southern Connecticut University. That same fall, Baker visited the Institute Library for the first time—brought along by one of the library’s board members. Baker was instantly taken by the rich history of the library, and began investigating the Institute’s past as part of his own research. By the time his two years at Southern were over, he had befriended many of the Institute’s board members and was offered a newly created position as executive director.

As part of his final project at Southern (before his directorship at the Institute), Baker mailed out a survey to all two hundred members at the time. Part of the fact-finding project solicited basic information: why members joined (everything from encouraging small libraries to “support[ing] Will Baker in all his endeavors”), how often they visited (less than four percent visited once a week or more), and how many books they borrowed (almost half had never checked out a book).

The survey was also forward-looking. Baker wanted to know what members liked best about the library—and what they thought stood to be improved. Their answers sounded a ringing note of approval for Baker’s vision of “library as place.” Users cited the literal space at the Institute as its most attractive feature—a “haven,” as one respondent wrote, “where one can focus and be productive.” They eagerly proposed introducing debates, game clubs, and instructional classes. The simple addition of coffee and tea was the most popular proposed change.

…

The most worthy spirit of the library, Baker believes, can be found in the run-up to the Civil War, when the Institute was one of the few safe spaces for abolitionists to speak out in New Haven. (Uncharacteristically, Connecticut was a pro-slavery Northern state—the result, Baker surmises, of Southern business interest and the omnipresent legacy of Eli Whitney’s cotton gin.)

Baker has a favorite story from the era. During the 1850s, an abolitionist was invited to speak at the Institute, ruffling the feathers of New Haven’s Southern sympathizers. Determined to derail the speech, one local copperhead interrupted the visitor and began to muster a mob of indignant audience members. As the gathering seemed poised to dissolve into violent disarray, an elderly woman stood up to denounce the young rabble-rouser. Following her principled lead, a handful of other library members surrounded the man and began pushing him away from the crowd. The old lady, however, insisted that he sit politely through the lecture—guaranteeing that he learn his lesson in the truest sense.

Baker’s anecdote presents a kind of Holy Grail of social learning. The collective teaching of an old lady and a motley New Haven crowd suggests what civil discourse at its best can bring to those who agree to come together and talk together. Indeed, two-sided discourse is precisely what can get lost in an era dominated by the one-way transactions of the technological world.

The legend of the old lady isn’t the only one Baker likes to tell. “There are so many great stories that people have of while doing research in the library, pulling a book out and finding one they wouldn’t have encountered,” he says. “Or backing up into someone, and finding out they are working on complementary projects.”

These serendipitous encounters, of course, only happen in well-trafficked libraries. Still, while membership has risen under Baker’s tenure, he acknowledges that recruitment efforts alone will not be enough to carve out a new and permanent niche for the library. The real grist of his agenda as Director will be to introduce new programming to the library—giving new members a real “reason for them to remain.”

In the fall, many of the plans proposed by the library’s members will finally come off paper and into action. Baker hopes to launch the Institute’s first lecture series, on the theme of civil discourse—as he describes it, “civil discourse about civil discourse.” Book clubs and classes are also in the works, along with eight exhibitions of local artists.

“There’s great potential for the Institute Library to attract downtown people in for lunchtime programs or after work for discussions, book talks, etc.,” the public library’s DeNigris wrote.

Baker has plans for more avant garde performances as well; he hints at the possibility of bringing an old friend, “the last link to the last great generation of sideshow performers,” to put on his famous sword-swallowing act on the library’s second or third floor.

Baker knows he is fighting an uphill battle. He admits that computers, not libraries, are the perfect “portals to information.” But accessing information isn’t the endgame of Baker’s brand of education. Engaging with information—not just reading books, but truly discussing them—is the far more difficult mission of good libraries and good librarians. The “portal” Baker envisions is more than a few clicks of the mouse away, but still, he believes, well within reach. The question now is whether anyone else is willing to climb through.