The Peru that Yale librarian Daniel Mugaburu left with his family at age thirteen was a broken country. On August 8, 1990, the night before his departure, the price of gasoline had risen by 3,000 percent. The highway into Lima, once bustling with street vendors and microbuses from the seventies, was lined with mounds of rotting garbage. Terrorist bombings had forced Mugaburu to do his homework by candlelight for weeks at a time. But through the chaos, Mugaburu had always understood his city. Sitting on the back of his father’s motorcycle rushing over dirt roads as a child, Mugaburu pointed out the way to his father, every street corner familiar to him.

That familiarity changed when Mugaburu landed in the US. “I was stunned by the immensity of lights!” he later wrote in a letter to a friend. “Automatic doors? Ridiculous. Electric escalators? Holy shit!!!” Mugaburu’s new home in Hartford, Connecticut, was a strange land where classmates dumped heaps of food in the trash and storefronts kept their doors closed even when they were open.

Mugaburu started drawing maps by hand in order to understand his new home. He sketched outlines of the United States, searching for the home state he could barely pronounce. “Mapping was a way to familiarize myself with my whereabouts,” Mugaburu recalled. “It was about finding whether I belong here or not.” Mugaburu drew the streets that others only walked. When he could afford it, he went to a local convenience store and bought a professional map to check his work.

Mugaburu’s mapping project gained a global platform when Google released a program called Map Maker in 2008. Google Map Maker is an editing tool that allows ordinary people to shape, revise, and detail public maps of their communities online. Citizen mappers have put countries like Kazakhstan and Romania on the map and have kept maps of US cities current using satellite imagery, local knowledge, and GPS devices. With their help, Google Maps has become the most popular internet map, garnering 71 percent of online US map traffic in February and over two hundred million installations on mobile phones worldwide.

But as surely as Google has torn down the old hierarchy in mapping, it has built up a new one, restricting access to its data, allowing politics to influence its choices, and using free labor to turn a profit. Google has left behind a movement of citizen mappers eager to chart their communities but fearful that the spirit of independent cartography will be corrupted.

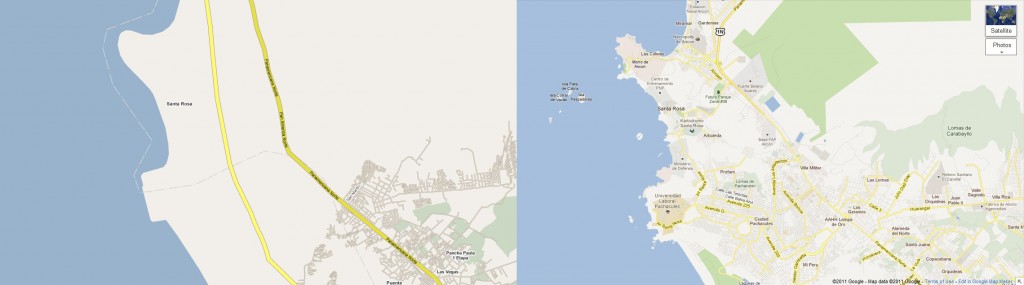

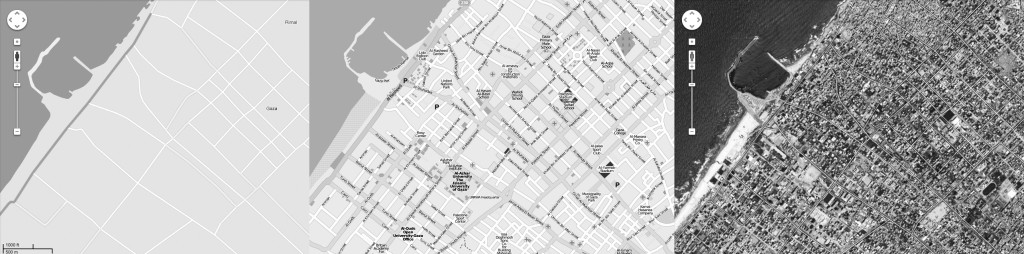

When Mugaburu first took stock of Peru’s status on Google Maps in 2008, he was dismayed by what he saw. “There were only a couple of cities and they were only half done.” Armed with his local knowledge of Lima, satellite images, and college credits in Geographic Information Systems, Mugaburu intended to equip Peruvians with the geographic data he’d thirsted for himself in Hartford. He wanted to put Peru on the map.

Mugaburu was drawn in particular to a blank spot that he knew to be Pachacutec, a slum of 200,000 residents north of Lima that the government refused to recognize. Peru didn’t have the money or political will to expend resources on Pachacutec’s displaced people, so it left the slum off of maps. The map’s blankness, in turn, justified the government’s assertion that there was no official settlement in Pachacutec. The result was a wasteland of a city with no running water, no electricity, no roads, and no health services.

Using Map Maker, Mugaburu drew the shoreline bordering the slum and all the roads that ran through it. When his edits were added to Google Maps, people in Pachacutec noticed and added street names, schools, hospitals, and a technical college. Now, Mugaburu said, “in the event of a disaster emergency personnel can get to places.” But maps have more than practical power, he explained. “We’re giving people who live in shantytowns some sense of place.” In his excitement, Mugaburu’s accent became more pronounced. He spoke for Pachacutec’s citizens: “Yes, this is where we are. We are on the map. This is where my business is. Come visit, just follow the driving directions.” When he’s not working at Yale’s Sterling Memorial Library, Mugaburu now travels to Google conferences to speak about mapping as a Google Map Maker Advocate.

Mappers like Mugaburu from around the world have been charting their hometowns, working to empower communities often lacking a common geographic currency. Kyril Negoda, who has made over twenty thousand edits on Map Maker, grew up in Karaganda, Kazakhstan, before moving to Minnesota at age fifteen. Karaganda, a mining town that once generated energy for much of the Soviet Union, withered during Negoda’s youth as energy technology changed and jobs vanished. As a boy, Negoda was a winner of the Kazakhstani State Olympics in geography, and he watched with a cartographer’s eye as population loss reshaped the town’s physical landscape. But no records were made. “Kazakhstan was going through all the political and economic changes after the Soviet Union. The importance of mapping fell by the wayside,” Negoda said. A town struggling to adapt to changing economic and demographic realities still relied on maps from the Soviet era to get around.

“I wanted to capture that changing landscape in my town,” Negoda explained. Giving people public access to their geographic data changed the way they related to their community. They took out their smart phones and traced Karaganda on Google Maps. When Negoda made a mistake, they logged into Map Maker themselves and fixed it. Karaganda was now known to the world—or at least could become known—and the investment that Negoda first made in his hometown “trickled down from top to bottom.” Karaganda’s cartographic presence also helped its business community recruit customers and bring back some of the jobs lost during Negoda’s youth. Mapped businesses are each assigned short Google Maps pages, where users can rate and comment on them, encouraging more hits and more customers, Negoda explained. Negoda and Map Maker have helped give Karagandans a voice in remaking their community.

Anas Qtiesh ushered his hometown of As Suwayda, Syria, through a similar transition. Before Qtiesh took to Map Maker, locals relied on their own memory for direction, streets were unnamed, and the official map was oriented with North to the left. State censorship kept citizens from acquiring the tools they needed to formalize their geography; Syria banned GPS devices, satellite images, and smart phones. “It’s a policy of keeping people in the dark,” said Qtiesh, who now blogs and maps from San Francisco. For Qtiesh, mapping is a tool of resistance against an apathy that impairs people’s personal sense of place and their commitment to political change. “Providing maps is a way of fighting back against that,” Qtiesh said. “It’s about people finding their place in a country.”

But the Google Map Maker revolution goes further. Mapping in all times and all places has given people tools to understand their space. But for the first time ordinary people, rather than governments or corporations, are drawing the lines. They’ll draw the lines not to snatch territory from neighboring states or to make a profit but simply because people deserve to know their way around. As Mugaburu puts it: “It can shift the power balance. It’s done by us, not by big governments. We know our countries best, our neighborhoods, and we have the power to change that.”

Google Map Maker claims to be part of a democratic revolution in how information gets produced. When communities generate the knowledge, communities can ensure that corporate or political interests don’t shape the way they get mapped. As Google said in a 2011 press release, “You know your neighborhood or hometown best, and with Google Map Maker you can ensure the places you care about are richly represented on the map.” Map Maker positions itself as a project by citizens, for citizens, which has garnered positive responses. In January 2012, the World Bank announced it would begin a partnership with Map Maker in its grassroots endeavor. Google may be a profit-seeking corporation, but volunteer mappers put in hundreds of hours of unpaid labor because they want to be part of a movement overturning the traditional hierarchy in mapping.

However, the project may be less democratic than it seems. Rhetorically, Map Maker latches on to the Wikipedia model of bottom-up knowledge production. In practice, Bill Rankin, professor of history of cartography at Yale, says Map Maker falls short of that vision. “It’s more like last.fm and Amazon where people provide information to a company and they don’t have a voice in how it gets used,” he said. “It’s less about people coming together to determine how their knowledge will be used and more about people providing free labor to Google.”

Negoda, who spent five hundred unpaid hours over two years mapping Kazakhstan, feels betrayed by the restrictions Google places around its mapping data. “Google needs to recognize its place as a partner to the community and become a good steward of the geographic treasure it is entrusted with. Until then, Map Maker represents little more than an elaborate front in a grand extortion scheme.” Earlier this year, Negoda dropped his affiliation with Google in protest over its policies.

Even Mugaburu, at first unerringly positive, acknowledged that cracks were beginning to form in his loyalty. “I started mapping in the good faith that Google will do the right thing. I don’t know other people’s threshold for good and ethical conduct, but they’re getting close to my threshold.”

When first joining Map Maker, mappers must hand over all legal claims to the data they will produce. Mappers can’t participate in decisions about how the data is used, receive no guarantees that it will live on should something happen to Google Maps, and surrender the right to share the data outside of Map Maker. Negoda and Mugaburu give over their data, trusting that Google will handle it in the best interests of the mapping community.

Rather than make freely available the data it freely acquired, Google places strict limits around the use of its mapping data. OpenStreetMap, an alternative to Map Maker that has a weaker global presence but is growing in popularity, allows people to use its data for whatever purpose and on whatever platform they see fit. Google, on the other hand, restricts access to its data in order to maximize profits. Under the Google Map Maker License Agreement, mappers are prohibited from using non-profit open source tools, like OpenStreetMap, to work with data introduced on Map Maker, killing the possibility of collaboration in what is billed as a collective, citizen-centered project. Another stipulation in the License Agreement prevents for-profit groups from displaying Map Maker data, jeopardizing Google Maps’ capacity to build small business in developing nations.

Mappers like Mugaburu are willing to accept these limitations so long as Google doesn’t ask customers to pay high prices for the product they’ve helped produce for free. But prices for Google Maps services are rising. In October of 2011, Google announced that independent web developers whose sites feature Google Maps must pay four dollars for every thousand Maps views over twenty five thousand. Though larger Web sites have always been subject to fees, the price hikes prompted Apple and FourSquare, a social media service, to switch from Google Maps to OpenStreetMap for parts of their applications. Negoda may sound like a man with a grudge when he calls Map Maker a “grand extortion scheme.” But as long as Google continues to recruit free labor under the banner of bottom-up citizen mapping, it can’t guard its data for ever-steeper profits without mappers and viewers questioning its motives. Representatives from Google did not respond to multiple requests for comment on its pricing and other policies.

With final decision-making power concentrated in a group of executives, dubbed the “Google gods” by Mugaburu, data for politically sensitive locations is often ignored. Active edits to the map of Cyprus were suppressed and the country was left blank because Google feared offending the Turks or Greeks with their use of one language over the other. Map Maker has closed editing in Gaza, where people lack access to basic geographic data, even as they face threats of violence. In contrast, during the Gaza War of 2009, OpenStreetMap issued a call for contacts familiar with Gaza’s geography to fill its online map. “Information is our most powerful tool towards peace and understanding,” Mikel Maron, a Board Member of the OpenStreetMap Foundation, wrote on his blog at the time. “Let’s work towards openness and freedom.” OpenStreetMap now features a detailed map of roads and public services in Gaza. Asked by e-mail why he thought Google refused to open Map Maker to Gaza, Maron responded in a few terse sentences. “There is nothing political or financial to gain from opening up in Gaza,” he wrote. He speculated that “Google also has a substantial Israel presence.” Google is likely concerned about political spam, but to Maron there’s no defense for prioritizing corporate anxieties over equal access to information.

The combination of Google’s price hikes and restrictive policies have sucked the spirit from Mugaburu’s mapping efforts in the United States, though he plans to continue mapping in Peru. With mappers discouraged from voicing their concerns, Negoda and Mugaburu hope that consumer pressure will lead to reform. Pressure from activists recently compelled the World Bank to revise its relationship with Map Maker—“if the public helps to collect or create map data, the public should be able to access, use, and re-use that data freely,” a March 2012 press release from the World Bank said—but a more widespread boycott remains unlikely.

A geography teacher at St. Thomas Elementary School in New Haven recently asked Mugaburu to speak to his class about mapmaking. Mugaburu began developing ideas for demonstrations and activities and asked his supervisor at Google, Jessica, if she could provide stickers and other props. “I don’t think it’s a good idea for you to do this,” she told him. Mugaburu was discouraged; he’d been excited to share his mapmaking efforts with a new generation of cartographers. Jessica explained that an internet protection law prohibits anybody under the age of thirteen from having an e-mail account. She didn’t see why Mugaburu would want to promote mapmaking among kids too young to sign up for Google. As Mugaburu understood her, “if they can’t map, what are they good for?”

Mugaburu wants to give others a glimpse of the power of mapmaking, of the personal and political transformation that becomes possible when people get together to chart their world. He wants Google to recognize its obligation to the mappers who have offered their service under this ideal. And above all he wants to grant the next generation the gift of knowing that there’s a tool as powerful as words or songs or dances to understand its place and tell its stories. Google, on the other hand, just wants more mappers.