“Stearns, this is bad philosophy and it’s bad science. Defend yourself.”

It’s the early 1970s, in a small classroom at the University of British Columbia. Halfway around the world, the Vietnam War rages on. In our quiet corner of Canada, however, there’s nothing but the sound of agitated footsteps as Stephen Stearns ’67 paces, waiting to know whether his outrageous Ph.D. proposal will be accepted. The topic is the main problem: Essentially, what Stearns has written proposes the formalization of a completely new area of evolutionary biology—life history evolution.

If the committee decides against him, his career as a scientist is finished before it’s even really begun.

—

Life history evolution theory defines the stages of organisms’ lives and aims to explain why they invest different amounts of time and energy in development, fertility and death. Organisms allocate limited resources intelligently—energy used for foraging, for example, may decrease the amount available for reproduction.

Researchers study traits including age of maturity, age at first reproduction, number of offspring per birth, and duration of juvenile development. Natural selection, the theory says, ultimately works to ensure the largest possible number of surviving offspring.

In a sentence, life history theory is the realm of biology that tells the story of life itself.

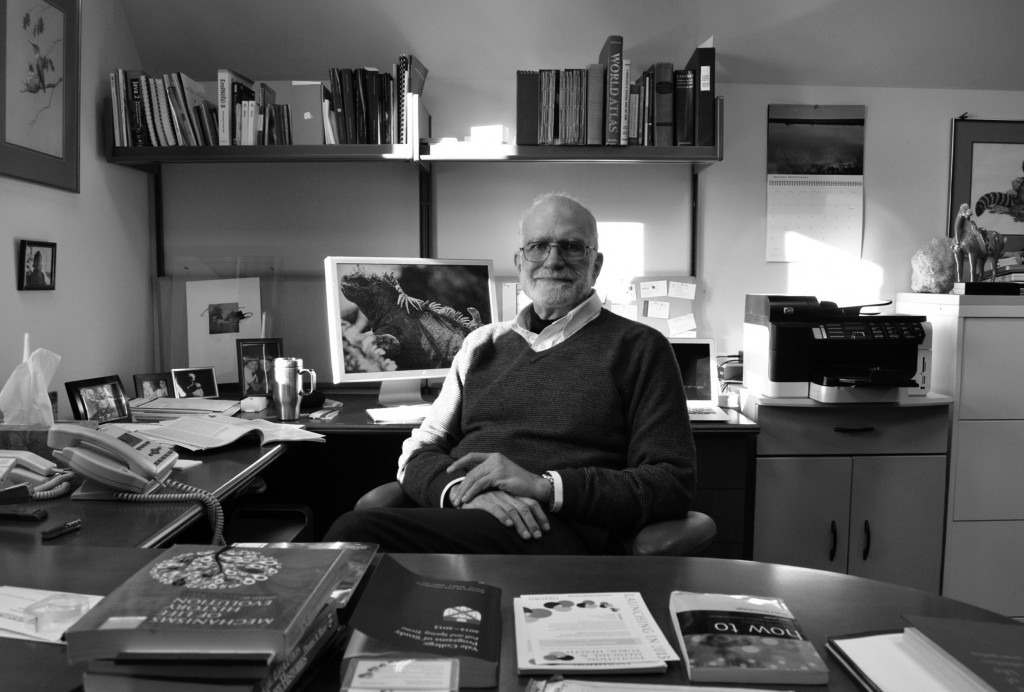

Currently the Edward P. Bass Professor of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at Yale, Stearns has made some of the most significant contributions to the field. Just last year, he and his collaborators found evidence that humans are still evolving. They analyzed existing data from a long-term study and concluded that women are evolving to “be on average slightly shorter and stouter, to have lower total cholesterol levels and systolic blood pressure, to have their first child earlier, and to reach menopause later than they would in the absence of evolution.” In other words, they found that selection is making sure we have more opportunities to reproduce.

“I walked up and down in the hall for forty-five minutes while they talked,” Stearns says, referencing his extended wait while the Ph.D. committee made their final decision. “The usual time was five to ten minutes.”

It’s a frosty afternoon in January, one of the coldest days we’ve seen this year. We’re sitting across a low table from each other, on worn leather loveseats; he’s wearing a dark blue vest, a lighter blue oxford, a bluish-gray sweater, blue jeans, and brown shoes. All the blue complements his faded blue eyes, which smile a bit at the memory.

“When they came out, they said, ‘Well we’ve let you through, but, you know, there were some really serious doubts,” he remembers. (In his quasi-memoir, Designs For Learning, Stearns phrases his conversation with the committee a tad differently: “We cannot tell from this document and this examination whether he is a fool or a genius. I suggest we take the risk and pass him.”)

As he relates this, he begins to fiddle with the pale floral coasters stacked on the table; at first, it seemed like an odd tic for someone generally so poised. His thumbnails, however, with their broad and craggy steppes, betray a nasty habit of nail-biting.

“I sent the introduction to the Quarterly Review of Biology,” Stearns continues. “George Williams, who was editor, published it. It became the most cited paper in life history evolution. Ever.”

That first paper would catapult Stearns to international prominence. (The rest of his Ph.D. thesis—the more conventional part—would not be accepted for publication for another eight years.) Once an undergraduate at Yale, he is now one of the most accomplished evolutionary biologists in the world. Over the course of his long career—which isn’t over yet, not by a long shot—he’s trained and inspired an entire generation of biologists. He’s founded two journals, authored over one hundred papers, and written four books. According to Google Scholar, his papers have been cited 18,513 times.

Aside from scientific research, Stearns takes great pride in his teaching. When I asked him about his former students, he spoke for twelve full minutes, recalling each person’s achievements in detail. Stearns’s students have gone on to important positions in science, in disciplines that range from anthropology to ecology. If—as biology asserts—the point of life is to continue life, then, intellectually, Stearns hasn’t missed the mark. Nowadays, he’s got academic grandkids.

Stearns’s own life mirrors his research. As a budding biologist myself, I like to think of it in evolutionary terms: his influence is as inexorable as the law of natural selection. From his cyclical journey through Yale and back again, Stearns knows that life is best marked by its uneven steps, that the key moments in one’s own life history—juvenile development, finding a mate, age of first reproduction—occur in unexpected places and times.

—

Stearns’s own story begins in the northwest corner of the island of Hawai’i. He was born in December of 1946, at the end of World War II, and grew up on a sugar plantation beneath the shade of Kohala Mountain, the oldest volcanic peak in the area. (Now, as a Yale professor, Stearns wears Hawai’ian shirts when the weather cooperates, a reminder of home.)

He comes from a family of educators. His aunt Mary had helped the Chinese government set up primary schools in China. When she was kicked out by the Japanese invasion, she went back to Hawai’i and helped the Hawaiian state create its primary school system. His mother was a teacher in Oklahoma—she then moved to Hawai’i, and was a schoolteacher before she met Stearns’s father.

Steve Stearns attended boarding school at Hawai’i Preparatory Academy (HPA) after fifth grade. HPA has a very good record of sending their students to top colleges on the mainland. Stearns was no exception, enrolling at Yale in 1963 at the tender age of 16. (He skipped sixth grade.)

Stearns grew up at Yale. His life as an undergraduate played out against the turbulent backdrop of the Vietnam War. The atmosphere on campus was incredibly patriotic, maybe even jingoistic, and Stearns had friends on campus who left to go to the front. “In ’68, it was good to be against the war; in ’66 and ’67 it was not good, at Yale, to be against the war. Yale was conservative that way,” he explains to me.

Despite the climate, Steve was an early war protestor. The fallout drove him out of his society, St. Anthony’s Hall, and cost him nearly all of his friends during his final year. “I felt a great release when that happened,” he says. “And basically I threw myself into my academics, and I had a great semester academically. I really loved my courses.”

Four years after matriculating at Yale, he received his bachelor’s degree in biology, graduating with honors as one of the top three students in biology.

“I would say that the basic thing that happened to me at Yale was that, yes, I did get a good education in some things, but Yale made me into a snob. And that wasn’t good for me,” he says. “I don’t see Yale as an unmixed blessing by any means.”

Perhaps Stearns found the culture of Yale in the sixties stifling or overly intellectual. As a sixteen-year-old college student, he was much more sensitive to the striking effect Yale’s name often has for people outside its walls.

Listening to Stearns talk about Yale reminds me of our own experience here, and raises a larger question: after four short years, what have we actually learned? This year, Stearns is my senior thesis advisor. In May, I’ll be graduating in Branford College, in the same courtyard where Stearns received his undergraduate diploma four and a half decades ago. I find it an odd parallel, representative of the cyclical nature of institutions. Forty-six years hence, will I be a Yale professor with a neatly trimmed white beard? (It’s not outside of the realm of possibility, but I don’t think I’m nearly professorial enough.)

I don’t yet know how Yale will affect my life history—my future partner, family, and career—but, so far, my experiences have been almost uniformly positive. Stearns has been a large part of that. As a mentor, he’s not afraid to be brutally honest. “Get your fucking life together,” he told me at one of our meetings this year. I had fallen behind with research for my senior essay and spent most of my time on less academic activities instead of on reading papers. He apologized later, at our next meeting, but I told him there was no need. I think he saw some of himself—perhaps one of the more desultory parts—in me, and reacted in a way that he thought would jolt me out of self-sabotage.

Stearns is aware of Yale’s insularity, and the danger that knowing everything (i.e., terminal narcissism) poses: “I’m especially sensitive to the capacity that Yale has to convince ambitious young people that they know what is best for the world. And I think they’re very dangerous.”

—

Immediately after he graduated from Yale in 1967, he won a prestigious fellowship from the National Science Foundation to get his Ph.D. in marine biology from the Scripps Institute of Oceanography in La Jolla, California. He lasted a full six weeks before dropping out. He didn’t think the requirements were worth completing.

“I was very aimless,” he said. “I traveled back and forth across the country—I actually drove, in my car, all the way across North America.”

After his brief Kerouackian detour, Stearns moved back to Hawai’i and lived with his parents. He got a job at a medical clinic in Honolulu, helping to computerize its medical records. He was fired after three months because his behavior was apparently disturbing the nurses. “I think that I was young, insecure, arrogant, and made inappropriate comments,” he said. “So, that was a kick in the head.”

It’s this arrogance, really, that defines Stearns. He’s convinced—and always has been convinced—that he’s right. I pressed him.

“That was where I started to realize that Yale had damaged me and that I would have to change what I had become at Yale if I wanted to be on good relations with the people I worked with,” he said. “However, I still have scars, and I still try to avoid the sorts of experiences at Yale that damaged me.” He didn’t say what those experiences were.

That earlier arrogance, though, has mellowed over the years. Really, it’s become what it always was: relentless dedication to truth.

Life history evolution might say something worth noting, here—it’s explicitly concerned with marking life’s milestones, experiences that transition an organism into the next stages.

During the course of Stearns’s humbling non-scientific wanderings, there was a bright spot: Steve met Beverly. A friend and fellow environmental activist, Tony Hodges, advised Steve to give her a call. On June 19, 1970, the two went on a blind date to a Grateful Dead concert. They’ve been together ever since.

Meeting Bev gave Steve purpose, I think. He found an anchor at a time when he needed centering, when hopping between different jobs and locations wasn’t enough. Life history tactics—and romantic novels—suggest that their meeting was a turning point in both of their lives.

Another turning point: their first son, Justin, was born during the last nine months of Stearns’s Ph.D. research at UBC. Their second, Jason, was born two years later.

Jason is now a writer living in Africa; he’s an expert on the Congo, and his book Dancing in the Glory of Monsters explores the sensitive subject of the seemingly endless civil war. He’s just had a son (Stearns isn’t only an academic grandfather), and is busy ensuring that his life history will indeed evolve. Despite his full schedule, Jason found time to shoot me a short email about his dad.

“In many ways he hasn’t changed much at all––he still comes home every afternoon before six, doesn’t work on Sundays, watches football with the sound off (he hates advertisements and doesn’t like the commentators much), beats us all at chess, and cooks a mean steak.”

Now, I’ve never had a Stearns steak, but I can only assume they’re made with love. Stearns loves his work, but he’s always put his family first. He’s never worked nights or weekends, and has always been there for his boys.

“I was home with my boys when they were growing up; we didn’t have a TV, we read to them at nights, I was with them for Cub Scouts and Boy Scouts and all of that kind of stuff. And that’s irreplaceable,” he said. “Things happen to you when you get out of college that cut much closer to the bone of what life and death are all about.”

When Jason and Justin were 6 and 8, respectively, the family crossed the Atlantic, leaving their home in Portland and settling in Basel, Switzerland.

The move was difficult for the family. His sons in particular did not acclimate to the new school system, struggling with learning in a different language. They had moved to the city because Steve had taken a new job there, and he felt guilty that they had trouble adjusting.

As he cooked dinner one night six months after they had arrived in Basel, Steve had a heart attack.

At the time, he didn’t know what had happened, and shrugged it off. But the next day, he couldn’t walk to work and was sent to the ER. He was hospitalized for three weeks. The doctors told him it was due to stress, which wasn’t surprising: in addition to the move, Steve’s father had recently died and Steve’s job required him to be able to lecture in German within two years.

In Swiss culture, academia is highly regarded; professors are like tiny gods, with complete power over their domains. Naturally, this leads to god-sized expectations from subjects. Managing this academic pressure along with many others, Stearns was overwhelmed. His work was taking a toll on his health.

“While recovering from this near-death experience I realized that one of the reasons I was so stressed was that I was unconsciously responding to the expectations of my students and staff that I ought to fit their picture of a ‘Herr Professor Dr.’,” Stearns said. “I was not a Swiss professor; I was a kid from a sugar plantation in Hawaii.”

After 17 years of teaching at Basel, he left. In 2000, the Stearns family moved back to Yale at Bev’s behest. Jason and Justin were both in college on the east coast—Jason was an undergrad at Amherst, while Justin was just starting grad school at Princeton—and Bev, a journalist, wanted to stay in one place long enough to hold a salaried position.

“I gave up my job in Switzerland, which was better than my job at Yale in many ways, to give her that last chance to have the reward of recognition in a career,” Stearns said. They miscalculated, however—the print industry was in freefall, and journalism jobs were scarce. “Within a year of our arrival, Jason was in the Congo and Justin was in Cairo, and Bev was not able to find the job she wanted. We made the best of it.”

—

Stearns rarely does original research anymore. Instead, he primarily teaches. For him, it’s a form of immediate gratification: The way a teacher affects his students is very quickly apparent.

Nowadays, he focuses on the burgeoning field of evolutionary medicine, the intersection of evolutionary biology and medical science. As a discipline, it promises new treatments and therapies for many different diseases. He teaches both a seminar course and a lecture course on the subject at Yale, and they’re perennially rated very highly on those all-important course evaluations.

In many ways evolutionary medicine is a natural segue from life history evolution. If life history theory tells the stories of life, then evolutionary medicine uses these stories to inform centuries of medical science. The breadth of application is stunning, and potentially life-saving. For example, researchers have discovered a new method of treating autoimmune diseases—multiple sclerosis and Crohn’s disease, among others—using worms generally found in pigs.

At Yale, Stearns’s methods of instilling the joy of discovery in his students have received university-wide praise. In 2011, he was awarded the DeVane prize for distinguished undergraduate teaching, given solely on the basis of student nominations.

His skill as a professor is the product of years of experience, from places as diverse as UC Berkeley, Reed College, and the University of Basel. He has pioneered new teaching methods, which he uses in the evolutionary medicine seminar, all designed to allow students more autonomy over their own learning experiences.

Perhaps more importantly, his students and colleagues love him. On a snowy afternoon in February, I spoke with Gregg Gonsalves ’11, an AIDS activist and Eli Whitney student. When I met him, his face was wrapped up in a multicolored scarf to protect it from the cold. He’s shorter than me, maybe 5’8”, and speaks with a very gentle voice. As an undergraduate at 40, he took Stearns’s introductory biology lecture course and was immediately hooked. And he was in the first cohort of the evolutionary medicine seminar in 2010.

“I’m almost double your age. Over the course of your life, you meet lots of mentors,” he said. “Steve was one of the most important ones.”

Gonsalves is currently working on mathematically modeling infectious diseases. It’s hard science, and he credits Stearns—specifically the seminar—with helping him realize that intensive scientific research was within his intellectual reach.

“Steve basically sucked me into the world of evolutionary biology and evolutionary medicine, and I found it absolutely transfixing,” he said. “I mean, I was about to go and take my partner and move to Europe, work in a lab, live in some Parisian garret, and work on HIV tolerance in monkeys. Steve had that kind of force.” He didn’t end up going, but he’s stayed in New Haven to pursue a PhD in the epidemiology of microbial diseases and take a position as co-director of the Yale Law School/Yale School of Public Health Global Health Justice Partnership.

Stearns teaches the seminar with a number of other professors from different areas (though most are from E&EB). The guest professors are a selling point for the students, said Paul Turner, the chair of the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology department and co-director of the evolutionary medicine seminar. The class emphasizes student interaction with research—not simply through reading papers, but also in discussion with the authors themselves. When the authors visited, students were required to attend dinner immediately following class, with the notion of speaking about concepts discussed in class in a more informal setting.

Like Gregg, I took the yearlong seminar in the spring of my junior year and fall of my senior year. During my conversation with Gonsalves, we reminisced about the course—guest professors, favorite topics, Stearns’s classroom manner—and I was surprised to note that the course’s DNA had not changed. Gonsalves and I got the same thing out of it, I think. We were treated as full colleagues, and expected to take the same amount of pleasure from learning as our teachers.

For Stearns, the course fuses teaching and research in a way that satisfies his unbridled curiosity. He may benefit more from it than we do.

“After about a decade and a half of feeling like a butterfly in a harness trying to change the direction of a supertanker, I’m discovering that the supertanker is starting to change direction itself,” he said, when I asked him about how he saw his role in advocating evolutionary medicine. “I’m not sure that the butterfly had anything to do it, but there’s at least more movement.”

But Steve’s accolades, impressive as they are, don’t totally describe who he is. Two things drive him: his ability to effect change in the world for the better, and his dedication to inspiring the same desire in his students.

“What I really believe in, as a faculty member, is that we gain tremendous leverage on the kind of impact we have on the world, if we can change young people’s minds and emotional states for the better, when they’re young,” he said. “That affects the whole rest of their life. And I now, at the age of 66, know that it actually works!”

Fitting, I think, for a guy interested in telling the stories of life.