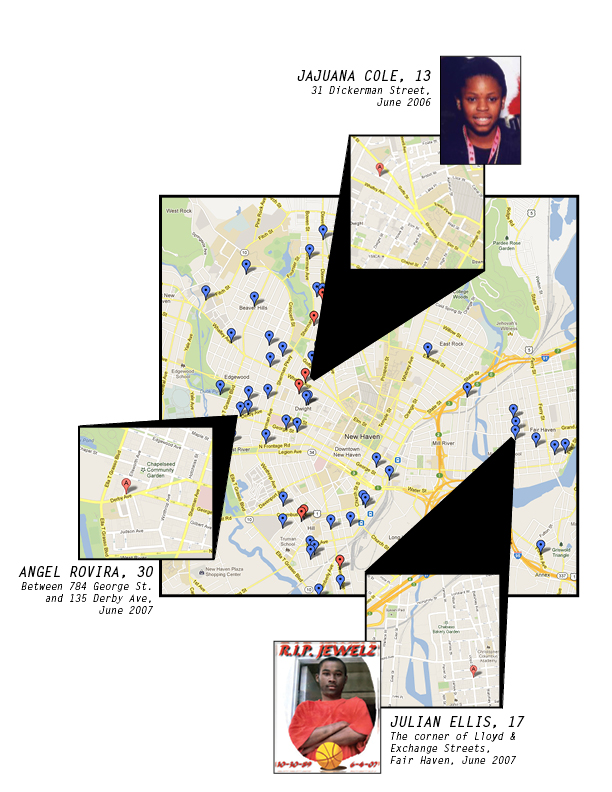

The night of Friday, June 17, 2006, was beautiful and warm as detective Al Vazquez and his partner drove through New Haven. The day’s work had been quiet, until they got a call over the radio, a disembodied voice saying a shooting had occurred in the Dwight neighborhood west of downtown. When he arrived at the scene, Vazquez was shocked to find EMTs wheeling a little black girl on a gurney. He watched as a paramedic hunched over her, vigorously pumping her chest. Vazquez didn’t need his decade of experience to know she was nearing death. Her name was Jajuana Cole. She was 13.

Around 11 p.m., Jajuana had been standing with Krystal Hammet, 13, outside of a party where they had some older friends. Three teenagers from the ‘Ville gang—a group modeled after Los Angeles’ Crips—drove down the street and noticed a member of a rival gang near the girls. Daniel Carter, 18, who was carrying a chrome handgun as he drove by, allegedly said, “There go some of them.” The boys parked on an adjacent block and took a shortcut through an alley. Tremayne Sanders, 16, had a black handgun, and Lamont Swint, 17, had a video camera.

Vazquez says the film Lamont shot is almost entirely black, with only pixelated silhouettes and muffled voices. Through the darkness, Krystal screams first: “Please don’t shoot!” The muzzle of a gun flashes about a dozen times. Then, Jajuana’s voice: “Oh my God, no!” The camera lowers to the ground as the boys run back to their getaway car. Carter mumbles, “I think I shot a girl.” The recording stops.

Krystal, whose back and leg had been grazed by bullets, dragged her friend to the second-floor landing of an apartment building. She cradled her friend while Jajuana pleaded, “Don’t let me die, don’t let me die.” Blood stained the floor. Paramedics arrived within minutes to take Jajuana to Yale-New Haven Hospital. Krystal begged to go to the same hospital, but the EMTs refused. Vazquez reached the scene as the girls were loaded into separate ambulances. The sight of the injured young girls reminded him of his own daughter.

Anyone watching Vazquez that night could not have known the shock and sadness and anger that lurked in his gut. He went about his work methodically: he asked the officers if there had been witnesses, and from the growing crowd, found a girl who had seen the incident and had been hit with shrapnel. Vasquez then called for another ambulance, and instructed an officer to stay with her. When he retells the story, his voice grows louder: “Do not leave her side,” he told the cop. “No one else talks with her. Stay with her.”

Jajuana died early the next morning. Her mother did not have the $795 to pay for a tombstone to mark her grave at Evergreen Cemetery. Vazquez broke his one rule he had never broken before: He promised the mother he would bring the murderers to justice. He interviewed the targeted gang member, informants, and eyewitnesses, and within thirty-six sleepless hours, he had arrested four teenagers, who all either confessed or informed on each other. Carter, who fired the fatal shot, is serving a forty-year sentence in prison.

Six years later, in November 2012, Vazquez broke his rule against making promises for the second time in his career. Participating in Project Longevity, a new initiative to prevent gang violence, Vazquez promised gang members that if they killed one more person, each would be punished to the fullest extent of the law, pursued by the combined forces of local, state, and federal authorities. Vazquez’s thinking has changed considerably since his early days on the police force. Where he once saw gang members as an evil force to be locked away, he now sees them as a group of misguided teenagers who lost their way, paying for mistakes with their lives.

Project Longevity is the latest initiative in the New Haven Police Department’s effort to improve its engagement with the community. Since returning to New Haven in 2011, Chief Dean Esserman has reinstated community policing, a model of partnership with community members Esserman helped craft as deputy chief in the early 1990s. Like many of Esserman’s recent projects, Project Longevity is not just punitive: It offers gang members the social services they might need to escape from a life of crime. Like Vazquez, the police department’s leadership now realizes that merely incarcerating gang members will not stop the violence, and they hope that these young men will take the escape route offered. But Vazquez knows he will have to follow through with a crackdown if shootings continue. If he does not, senseless deaths like Jajuana’s will continue to occur.

“Those images never escape you,” Vazquez says, as he remembers Jajuana’s little body on the gurney. He blinks, as if to push back tears from shining eyes.

—

Vazquez could easily have been one of the shooters—or maybe the target—that night in June. But from a young age, he avoided life in a gang, rejecting any of the attractions that the life might have offered, in order to pursue his dream of becoming a police officer.

Born in Middletown, Conn., in 1968, he spent his childhood shuttling back and forth between Puerto Rico and New England. Unable to support him financially, his parents sent their two-year-old son to live with an aunt in Puerto Rico. After four years he returned to Middletown, but his mother and father fought often. They separated when Vazquez was ten years old, and he travelled back to Puerto Rico.

“I always wanted to be a cop,” Vazquez tells me. He fantasized about catching the “bad guys,” accelerating a police car with lights flashing and sirens shrieking. Either in spite of or because of his chaotic childhood, Vazquez saw the world in absolute terms of good and evil, and he dedicated his life to being on the right side of the divide.

From the moment he entered middle school in Puerto Rico, Vazquez was pressured to join a gang. He desperately needed the money the lifestyle could provide, but he resisted their advances and was severely and constantly beaten for it. Instead, he took a job in construction during school vacations. Houses in Puerto Rico were built anywhere space was available, sometimes even on the edge of a cliff, so almost all the construction had to be done manually. As a 12-year-old, Vazquez carried 50-pound buckets of cement up a ladder to lay as the roof. The labor was exhausting, but Vazquez was satisfied that he made his money honestly. His classmates, who viewed him as an outsider, referred to him as the “gringo.”

In 1985, Vazquez moved to New Haven, where he has lived ever since. Neither of his parents could afford to take him in, so he was forced into a foster home. He enrolled in Wilbur Cross High School, where gang members again tried to lure him into their lifestyle. They told him he had to sell drugs for them in the projects near Ashmun and Webster, which have since been demolished and are now the site of the Yale Police Department headquarters. Once, when Vazquez refused to participate, a gang member pulled a knife on him. Rather than back down, Vazquez prepared to fight him with his bare hands. Luckily, an older gang member intervened, telling the youngster, “Don’t touch him. Leave him alone.” Vazquez was so adamant in his rebuffs that gangs eventually stopped trying to persuade him.

Role models were rare in New Haven’s foster homes and projects. Today, Vazquez says he wishes the department had implemented community policing when he was young. He wishes there had been a local cop, with whom he could have shared his difficulties, someone he could have emulated. I ask Vazquez why he was never tempted by the security and money joining a gang could offer. He thinks for a moment. “I really don’t know. I guided myself through. Sometimes answers are simplistic.”

Vazquez worked multiple part-time jobs to support himself, first as an attendant at a Mobil gas station and later as a mechanic at a Mercedes-Benz dealership. When he turned twenty-one, he applied to be a police officer. He was the first in his family to enter a career in law enforcement. He passed the written, physical, and oral exams, and with thirty-two others, all raised in New Haven, Vazquez was sworn in as a police officer on January 21, 1992.

His first patrol sent him on a walking beat in the Dwight-Kensington district, the neighborhood where he would one day investigate Jajuana’s murder. Esserman’s community policing put cops on foot or bicycle on beats around the city instead of in patrol cars to descend on crime hot spots. “We are not exchanging hugs for handcuffs. We are doing both,” Esserman told me. “We are building relationships on both sides of that badge.” When he first pioneered the model between 1990 and 1997, crime in New Haven fell by forty-one percent, compared to a ten percent drop in crime nationally.

Abandoned houses lined the blocks of Vazquez’s beat, providing hideouts for gangs and places to stash drugs and guns. Two groups dominated the area: the Kensington Street Internationals and the Ghostbusters. Corny as their names were, the gangs were ferociously dangerous. Once, Vazquez and a partner were walking their beat when shooting broke out at an intersection and the pair was caught in the crossfire. They could not see any shooters, and the echo of shots bouncing between the houses prevented them from locating the bullets’ origin. Vazquez ducked behind a car and called for backup, but all he could do was wait for the gangs’ ammunition to run out.

Using one of his favorite and oft-repeated phrases, Vazquez says he was “full of piss and vinegar” in those early years as an officer. After witnessing violence during high school, he was eager to clean up the streets of New Haven. At the time, he thought that meant “running after the drug dealers, the gangbangers, and the shooters, locking them up, seizing the guns and the drugs, and putting them behind bars.” Though he would later realize the situation on the streets was far more complex than that, Vazquez spent his rookie days thinking he was a soldier in an enduring battle against evil. Discord had broken his family, but Vazquez would not let lawlessness do the same to his city. He fought back this time, fiercely, as he assailed gangs with one arrest after another.

After a few years of walking a beat, Vazquez was recruited back to headquarters in 1996 for a temporary assignment to the detective bureau, the unit he would later oversee. Patrol officers routinely worked stints as investigators to get a taste of detective work, but also so the detectives, who Vazquez calls the “old-timers,” could have a connection to informants on the street. Vazquez was initially hesitant about his placement, thinking he would hate the work. Detective work is much slower-paced than a cop’s. After going from a uniform to a suit, you have to work methodically, thinking constantly about your next move rather than reacting to whatever the street throws at you.

“There you have it: the dead body. Figure it out,” he tells me. Sometimes you have eyewitnesses and sometimes you have nothing. On one chilly January night when temperatures sank into the negatives, Vazquez found a body in a parking lot with a gunshot wound to the head. Years later, the case is still cold. Other times, as with Jajuana’s homicide, you have eyewitnesses and suspects immediately, and the case can be closed in hours.

At the end of his three months, Vazquez had solved twelve of the sixteen cases he had been assigned. His new boss wanted him to stay on as a detective, but his union contract forced him back to a beat. Eventually, a compromise was reached and Vazquez joined the drug enforcement task force.

Vazquez says his first days as a detective gave him a new worldview. Although he did encounter cases like Jajuana’s, in which crime destroyed the life of an innocent person, the situation was often morally complex. Many of the homicides resulted from gunfights between gang members: chance alone determined who was the victim and who was the murderer. In some cases, the victim was a murderer himself. The categories of good and evil that he had sorted the world into suddenly seemed overly romantic. It was often kids he was chasing down, young men who had fallen into gangs because the city offered them no alternative. “You realize it’s a different game,” he says now. “Nothing is that easy, that simple, that straightforward.” Though his investigations into crimes like child abuse deepened his awareness of how cruel people can be, Vazquez changed his objective. Life was more complicated than being a crusader for good against evil. He now aimed to protect “the innocent, the weak, and the deprived,” which included not only law-abiding residents like Jajuana, but also gang members who had made a few wrong choices.

Sometimes Vazquez is overwhelmed by each day’s cases. “People don’t realize the extent of evil in the world,” he tells me. He almost never discusses his work with his wife Ada or with his children. Unlike his tumultuous childhood, Vazquez wants to keep his family safe and secluded from what he has seen. But sometimes the silence worries Ada. When Vazquez leaves after a midnight call, she sits up, wondering if he is all right. “Every time he walks out the door, I say a little prayer,” Ada tells me. “It’s nerve-wracking.” When her stress gets too high, she calls him, and he reassures her, “Don’t worry. We’re still out here looking for the guy.”

A year after Jajuana was murdered, Vazquez investigated the June 2007 killing of Angel Rovira. Mitchell Joyner, 17, approached Rovira as Rovira walked home from work. A native of Puerto Rico, Rovira did not understand Mitchell’s demands for his gold chain, so he kept walking. Mitchell pulled out a semi-automatic handgun and fired two shots into Rovira’s back, hitting an artery in his heart. The victim ran to his apartment building a block away and fell down at the entrance. His wife and his four-year-old son found the body.

Rovira’s father flew to New Haven from Puerto Rico and began searching for the killer himself. When Vazquez heard this from informants on the street, he worried Rovira’s father would lose his life, too. Vazquez sat the family down and told them to not interfere. The father objected. Vazquez might have easily defused tensions with a promise to find the killer, but he was unwilling to break his rule.

Vazquez had information that pointed to Mitchell as the killer, but he needed a direct confession. In an interrogation that he said felt like running a marathon, Vazquez took advantage of Mitchell’s remorse. The teenager sobbed as he admitted he pulled the trigger. “I can’t believe I just got this kid to tell me he did it,” Vazquez thought, as he put the boy in handcuffs. He was working not against the abstract, innumerable forces of gangs, but against one 17-year-old boy with true regret in his eyes. Vazquez felt no joy. He felt like the bad guy.

—

I first meet Al Vazquez on a snowy November evening at the police department’s headquarters. His dark brown skin is striking against his white button-down. The first lines of silver mark his hair and the thin mustache above his lips. He looks tired. The night before, he woke up just after midnight to a phone call informing him of a shooting and a baby’s accidental death. He rests his hand on his holster as we ride the elevator to his third-floor office. Most of the other cubicles are empty, but the phones continue ringing nonstop.

Vazquez has been nervously awaiting the verdict in the trial of Troy Jackson for the 2007 murder of Julian Ellis. With community policing restored under Esserman, the department is aiming for a personal connection with the community. After five years of negotiation, Vazquez had convinced a woman to step forward as a key witness for the Jackson trial, even though she was deeply concerned about retaliation. When I first met Vazquez, he was on the phone with her, reassuring her and offering to meet at the courthouse before she was set to testify the next morning. His two other witnesses are less upstanding citizens: both are currently incarcerated. One, who is doing time for drug-related charges, “went south” last week, and now denies his earlier testimony, presumably after being threatened by Jackson’s gang while in prison. He recanted his 2010 statement where he identified Jackson as Julian’s killer. “The detective”—Vazquez—“told me what to say.” “He gave you all the details?” the state’s prosecutor asked. “Yes.”

In November 2011, Esserman, who had served as deputy police chief when Vazquez joined the force but most recently worked as Chief of Police in Providence, R.I, was called back to New Haven. As the fourth chief in three and a half years, Esserman had his work cut out for him. The department had gained a reputation for brutality and corruption, an enemy to the community it was supposed to protect and serve. The number of homicides was skyrocketing, tying the record for the most murders in one year. By the end of 2011, thirty-four had been murdered, and 122 had been shot. And after years of attrition and poor management, the department was severely understaffed.

Frank Cochran, the current chair of the Civilian Review Board, said the department has had trouble recruiting officers from New Haven, a legacy of its former resistance to collaborating with the community. Vazquez currently has only thirty-eight of the sixty-one detectives that are supposed to fill his unit. In overseeing the division, he is doing the work of a lieutenant, but due to gaps in the department hierarchy, he remains at the lower rank of sergeant.

With community policing and Project Longevity, Esserman is applying strategies he used to reduce crime when he was chief in Providence, focusing on the small groups responsible for most of the city’s gun violence, rather than targeting everyone in certain neighborhoods as potential lawbreakers. “I am not bringing a new message or style to New Haven. I am bringing back the old New Haven policing.” Esserman told me. When he was deputy chief in New Haven, Esserman had created Connecticut’s first gang task force in the hopes of negotiating with rival gang leaders to end conflicts before their arguments became deadly. “We were one of the centers of American progressive policing,” Esserman says.

As one of many changes to the department’s leadership, Esserman promoted Vazquez to head the department’s Major Crimes Unit in April 2011, giving him responsibility for supervising the investigation of all homicides and shootings that occur in the Elm City. “He is one of the best detectives I have ever met,” Esserman told me. “If I, God forbid, ever had a family member who was a victim of a crime, I would want Sgt. Vazquez on the case. I know he would bring justice to my family.”

Vazquez had often criticized the strategies former chiefs implemented to fight against gangs, but they refused to listen to his suggestions. Yet he and a few others like Assistant Chief Luiz Casanova, who Vazquez trained seventeen years ago, never stopped practicing Esserman’s strategies. “Community policing is the only way to do policing,” Vazquez says. ““There is a mentality that police work is just responding to calls. But there is more than that.” Vazquez has been more than happy to oversee the implementation of community policing in his unit. So far, it has been working: Last year, shootings and homicides fell by nearly half. This year, there have been five non-fatal shootings, while by the time in 2012, there had been eleven.

Yet the city’s gangs have not entirely disappeared. Yale University researchers working with the police have identified nineteen active gangs with nearly six hundred members, some of whom have already been incarcerated in recent sweeps. As the police department’s structure changes, the gangs also adapt, moving their operations underground. They no longer perform drug deals on street corners as they did in the 1990s, but instead tell customers to call a middleman who will set up a deal. Their technology is more sophisticated. They have heavier firepower and clever new ways of storing drugs in cars’ hidden compartments.

Still, Esserman’s community policing model has been working so far. In January, after days of deliberation—usually a bad sign, Vazquez feared—the jury in Troy Jackson’s murder case returned a guilty verdict. Jackson raised his chin to the ceiling, as if readying for a noose, while the jury forewoman read him his crime: guilty of murder in the shooting of Julian Ellis. Another juror cried softly. In mid-February, Vazquez listened intently as the judge read Jackson his sentence of sixty years in prison.

—

Vazquez’s changed perceptions of the gang members are epitomized in Project Longevity, where community policing is taken to its logical end. It communicates directly with gang members, treating them as equal members of the community, where before they had been the enemy, terrorists, outsiders in their own neighborhoods.

At the end of last November, U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder, Gov. Dannel Malloy, and Sen. Richard Blumenthal gathered with local leaders in the tallest building in New Haven, the Connecticut Financial Center, to announce the start of Project Longevity. The comprehensive plan combined aid from social service providers — the carrot — with the punitive force of police, prosecutors, and the U.S. Attorney General — the stick. Similar programs have successfully reduced gun violence in neighborhoods in Boston, Chicago, and Cincinnati, the project’s backers say.

“Project Longevity will send a powerful message to those who would commit violent crimes targeting their fellow citizens that such acts will not be tolerated and that help is available for all those who wish to break the cycle of violence and gang activity,” Holder said from the podium.

A key tactic for Project Longevity is the “call-in,” a sit-down meeting between gang members, social service providers, and law enforcement. On a Monday evening in November, the Hall of Records was likely the safest and most dangerous place in the city as twenty-five members of two rival gangs filed in for separate meetings. No longer relying on sweeps to incarcerate gangbangers, Project Longevity offered them a choice. It saw the teenagers seated before Vazquez as empowered moral actors, able to choose the right path if offered to them. Cards were distributed, printed with one telephone number that could set up any social service necessary: job training, substance abuse therapy, counseling.

Though he says he is normally shy as a public speaker, Vazquez delivered an ultimatum to the gang members from the Newhallville and Dwight neighborhoods. “I am sick and tired of the calls,” he said to the groups. Vazquez laid out the two different paths gang members could take: One could save their lives; the other would lead them to rot in prison. If a single gang member is implicated in a shooting or homicide, local, state, and federal authorities will increase surveillance on each member of the gang. He could see the hurt in the young boys’ eyes as he spoke. “Aren’t you tired of doing this? You’re killing yourselves,” he told them.

After the first call-in, only three attendants called Project Longevity’s service providers, but the city’s violence quieted, with no homicides recorded between November and mid-January. The week of the second call-in, two people were killed: one in a botched commercial robbery that detectives are still pursuing leads, and one in a gang-related robbery that Vazquez’s unit quickly solved. (Vazquez could not disclose the name or gang of the suspect, since he is a juvenile.)

Yet some are betting against Vazquez’s hopes for Project Longevity, arguing that the program offers nothing new. Scot X. Esdaile, President of the Connecticut NAACP, told me that police have done stings on gangs for years. “I question the longevity of this project,” Esdaile told me. “The anti-violence initiatives last for a year or so, they start parading around, and then the violence comes back.” In the 1990s, Esdaile says police promised an end to violence when they locked up members of the Jungle Boys. But the shootings did not stop. Police went after the Kensington Street Internationals. Then the Island Brothers. Then the Newhallville Dogs. The strategy did not work. The city continued to bury its young. The solution, Esdaile says, is not only law enforcement and social services, but also jobs. “It is imperative politicians bring back jobs to urban areas,” he told me. “It’s the same situation in Chicago, in Detroit, Hartford, Bridgeport, New Haven.” He is especially concerned about the false hope Project Longevity’s social services may offer. If a boy “cuts his hair, gets rid of his dreadlocks, pulls up his pants, and shines his shoes,” but still can’t find a job, Esdaile worries he may return to the street bitter and more jaded than before.

But Vazquez and the department believe this time is different: with the backing of the community’s leaders and service providers, the police department is no longer cracking down on gangs alone. They are not hoping to lock up every one of the city’s gang members: they goal of Project Longevity is that they will not have to lock up anyone.

Vazquez sat in the audience at the second call-in. After the talks ended, he spoke to one man in his late twenties, whom Vazquez had met years before. The man was hunched over from a back injury. “I don’t know why I’m here,” the man said in Spanish, adding that he had abandoned gang life long ago. Vazquez told him Project Longevity could provide medical aid for his back pain and any other help he needed. Not everyone was there because they were still involved in gangs. “We want you to hear the message,” Vazquez told him, “and we want you to bring the message to your boys.”

Vasquez wanted to help them, and he was optimistic some would change. But he also knew that just one failure was likely to undo an entire group. He didn’t want to bring the force he had gathered against the boys, but he knew he would soon have to. In an odd take on the prisoners’ dilemma, where two prisoners have been replaced by the police department and the city’s gangs, each side has entered into mutual promises; each side depends on the other not abusing its trust. It’s a significant gamble, bet with the lives of New Haven residents: if successful, Project Longevity may save people like Jajuana Cole, Angel Rovira and Julian Wells, but if the violence continues, police will need to devote already strained resources to monitoring the killer’s group.

“If these kids failed to take advantage of what had been offered, I have to do what I have sworn to do for twenty-one years: uphold the law,” Vazquez tells me. “Whether I like it or not, I will do what I have sworn to do.”

But more than simply a gamble with the city’s safety, Vazquez is making a wager about human nature. Vazquez wants to believe that if given a chance, people are fundamentally good, that if things had somehow been different for Daniel Carter, Mitchell Joyner, and Troy Jackson, none of them would have pulled the trigger. Vazquez’s faith may seem ideal—quixotic, even—from one who has held the dying and sat across from their straight-faced killers.

With so much at stake, we can only hope he is right.

Graphic by Susannah Shattuck