Over lunch early in my freshman year, my friend Madeleine Witt told me she had been at a Yale Students for Christ retreat that weekend. I asked her how it had gone.

She smiled.

“I had the most intense religious experience of my life,” she said. “It completely changed my relationship with Jesus.”

For the rest of the day, I puzzled over those words. I’d thought religion was something people only found, or sought to deepen, in times of need. Witt was a talented artist at a prestigious school, with a warm, earthy demeanor and a strong sense of humor. She seemed to have her life in order. What could Jesus do for Witt that she couldn’t do for herself?

If God has been watching me this whole time, I hope He understands that before I got to college, I couldn’t help but be cynical about the usefulness of any particular faith.

My mother is Unitarian and my father Jewish (with an interest in Buddhism). I grew up with evangelical Christian neighbors. Their son—my best friend at the time—once saved me in the name of Christ in their basement. We were eight, and we had gotten bored with our plastic lightsaber duel. After that, I was heaven-bound for sure, so I stopped worrying about the hell I’d seen in “Tom and Jerry” cartoons, which had been the source of a few nightmares.

My parents sold me on Hebrew school by describing it as a set of language classes with a party at the end. At nine years old, I saw my religious education as just another chore. The Torah portion that I read years later at my bar mitzvah featured my namesake, Aaron, brother of Moses. His sons, Nadab and Abihu, get drunk and offer the wrong incense to God, who incinerates them in response. Aaron doesn’t mourn; to do so would be to question God’s judgment.

During the same few months I spent memorizing this passage in the original Hebrew, I came across a copy of Richard Dawkins’ The God Delusion, which served as my first serious exposure to a variety of useful concepts: cosmology beyond the book of Genesis, morality beyond the Ten Commandments, evolution beyond Pokémon. Dawkins can be strident at times, but I preferred him to God. I’ve been a nonbeliever ever since.

But by my second week on campus at Yale, religion became unavoidable. My new friends included a Catholic who kept her favorite Bible quotes on Post-It notes over her desk, a vegetarian Hindu who believed in karma, and an atheist whose hobby was sampling churches and listening without retort to believers. On hammocks and benches, during long walks and over long dinners, I struggled to comprehend the way they saw the world.

Witt’s religious awakening—like that of many of the converts I talked to—was outside my realm of understanding. I wondered if it was really a coincidence that her new relationship with Jesus began at a retreat where she’d begun new relationships with a few dozen Christian friends. Why would God wait to find her on a dock in the woods when she’d been going to church her entire life? Though I saw campus conversion as an uncommon tangent to college life, I needed to figure out how and why it happened—how Yale, which had intensified my atheism by exposing me to neuroscience and secular philosophy, had had the opposite effect on one of my closest friends.

For many, college is the first time we leave home. Religion, and the friends who come with it, can be comfortable and solid when life seems formless or uncertain. The students I met often spoke of a chaotic transition to Yale, and of finding peace in religious study, or the church choir, or moral philosophy with grounding holier than those of Aristotle or John Stuart Mill. I wondered if Witt, who sings in the Christian a cappella group Living Water, might have found similar comfort in joining a nonreligious group like The New Blue or Something Extra.

So I started looking for students who had undergone religious conversions while at Yale. Their stories were diverse, and three stood out in particular. An undergrad named Kim Fabian was fond of Christianity but saw no reason to join the religion, until an emotional crisis helped her find Jesus. Bijan Aboutorabi went from atheist to Catholic, one classic work of theology at a time. And Witt, it turns out, walked a long and winding road before her evening on the dock.

**

At Witt’s twentieth birthday party, I asked her whether she could introduce me to any friends who had become more deeply connected to Christianity while at Yale. She pointed to three of the people sitting on her couch, including Kim Fabian. While Fabian identifies as Christian now, she has doubts to overcome.

“I describe myself as a baby Christian,” she explains over dinner. “I’m still figuring a lot of stuff out.”

Her modest self-description marks a major shift from the behavior that got she kicked out of Sunday school at the age of seven.

“What’s the word for purposefully being antagonistic and arguing with people?” Fabian asks.

“Contrary?”

“Yeah! And I was a disruption.”

The church asked her parents to “reform” her and send her back, but they decided that she was fine the way she was. After a few churchless years, she began attending Unitarian Universalist services, which appealed to her spiritual side but left her somehow unsatisfied.

“There was this mentality in the church about tolerance, that all religions were to be accepted—except for Christianity.” Devout Muslims and Jews were welcome; while devout Christians weren’t exactly unwelcome, Fabian sensed antipathy toward the religion from her fellow Unitarian Universalists, and from herself.

Ever the contrarian, she entered a Bible study group at her high school, hoping to understand and finally dispel her own past view of Christianity. At first, the task seemed difficult. She met some Christians who used religion as a weapon, to chastise or exclude the less devout. From what Fabian knew of Jesus, this felt like hypocrisy.

But others in the group managed to combine serious religion with kind behavior, and soon became some of her best friends. As she spent more time with them, and began to read more humorous and humanizing account of Jesus’ life in a book called The Gospel According to Biff, her remaining antipathy disappeared. Still, after her time with the Unitarian Universalists, she felt that all religions held some truth—why choose between them?

It wasn’t until college that Fabian returned to Christianity. After a series of incidents, in which she says she was responsible for “mean, hurtful things happening to close friends,” she looked for a higher pardon. Her friends’ forgiveness was not enough to erase what she had done.

“I needed salvation. I needed a savior.”

Fabian has been a Christian ever since. Her newfound inner peace is apparent as I talk with her in the Buddhist meditation room at the base of Harkness Tower. She spends a lot of time here. It’s full of expensive-looking statues, and part of her paid student job is to make sure nobody steals them. She lights candles on the altar, waves a stick of incense in a complicated pattern, sets it down, and bows to a stone Buddha. Her hands are clasped; her face, expressionless. A few silent moments pass.

“What was running through your head, during that ritual?” I ask later.

“Devotion, I guess.”

“Devotion towards what? God?”

“I hope so! Otherwise, I’m in trouble.” She laughs.

Fabian plans to raise her future kids as Christians: “I just want them to know that no other person, or thing, is ever going to be enough. Jesus is enough.”

**

Bijan Aboutorabi has many questions for me. “The greatest overall utility for humanity? How do you measure that? Where does it come from?”

The basis of my own morality is under fire. I can answer this, I think to myself. I don’t need a Bible, just a third of Mill’s Utilitarianism and a dash of David Hume. I should really get started on Reasons and Persons, too.

Aboutorabi is good at engaging with uncomfortable questions. What is ethical? How do we know? How do we know anything, for that matter? Upon his junior-year conversion to Catholicism, he found himself in possession of a complete, rigorous set of answers. He is the only convert I met who I believe might have chosen the same religion had he spent his life in a library, without the persuasive influence of a single human believer. Aboutorabi’s conversion was the work of divine logic.

Though he identified as a “militant atheist” in high school, at Yale Aboutorabi found himself spending more time with Catholic classmates, exploring the roots of his own morality. In college, he came face-to-face with “serious philosophy,” which caused quite a few problems:

“Nothing in materialism seemed to explain the existence of qualia,” he says, sounding distressed.

In philosophy, “qualia” are instances of conscious experience: the taste of cake above and beyond the understanding of pastry molecules, or the understanding of music as more than a collection of sonic frequencies. Aboutorabi’s concern is common among scholars: if we’re just soulless collections of atoms, why does conscious experience exist? This is an important question, but he found no philosophical consensus as to the correct response.

Catholic philosophy offered an appealing set of answers; religious thinkers were bolder in their assertions than most modern secular ones. Aboutorabi says he read a great deal of C.S. Lewis and G.K. Chesterton but still “wasn’t able to flip the switch” toward faith.

On the last day of sophomore year, he asked a Catholic friend and convert how he’d entered the fold: “He told me he’d felt a sudden sense of total, all-encompassing love.”

Though he had then, and has now, almost no mystical life, Aboutorabi asked another friend what else might dissolve his uncertainty. When a response came back, he read and reread it until one day he realized he was “standing with one foot on either side of a ravine, which was growing wider, and I had to jump to one side or the other.” The choice, he says, was ultimately easy.

And so, without any singular mystical experience—no lightning strike or burning bush—Aboutorabi became a believer. On Easter of last year, he received his first Holy Communion and was baptized.

His story leaves me wondering, “So, atheism couldn’t answer your questions. Aren’t there questions Catholicism can’t answer?”

“A limit on human intellect is very different from something fundamentally unanswerable,” Aboutorabi replies. He knows there are parts of the metaphysical world he’ll never fully comprehend—the Trinity, the exact nature of hell—but he trusts that the Catholic Church has reached the right conclusions on all important spiritual matters. After all, they’ve been discussing those questions for the past two millennia.

His understanding of Christian philosophy makes my moral foundations begin to feel like bamboo poles to his concrete pillars: flexible enough to tolerate some stress, but not much to look at, and skinny enough that they might buckle under the weight of a difficult choice. As we part, he calls my attention to “the unshakeable conviction of the Apostles that they had seen Jesus rise from the dead.” He is convinced he’s seen the same light as those earliest of Christian converts—and the experience has left him, as far as I can tell, unshakeable.

I knew before our interview that Witt had been religious before Yale, but I was looking for specifics about the conversion.

“So, on a scale of one to ten, you went from, like… a four to a nine?”

“You can’t measure it on a scale like that!” she protests. We’re not speaking the same language, but if I listen hard enough, I might begin to understand what she calls “the most precious story in my life.”

The first church Witt attended was tiny and rural, but her family moved while she was in middle school, and the new congregation had a few more kids her age. She considered herself faithful, but describes that faith as misdirected.

“I wore a WWJD bracelet, because that was what I thought Christians were supposed to do. But I didn’t understand what it meant,” Witt says. “What would Jesus do in this situation? He’d do a miracle! How does that help me?”

In high school, Witt saw God as another authority figure she had to please, alongside her parents and teachers. With enough good deeds and pure thoughts, she’d earn God’s love and be a “good Christian.” She goes on to explain how wrong she was, that Christianity is unique, in that while “God asks everything of you,” God also knows that we are incapable of becoming worthy of his company through human effort alone.

I ask Witt what led her to see things in this new light. Soon after she entered Yale, Witt explains, she met students unlike anyone she had encountered at home.

“They were so committed to following Christ that they talked about Jesus like he was someone they knew,” she says, “Someone they could have an intimate relationship with. And this was something I was very curious about.”

At that first retreat, Witt heard a speaker discuss grace: the idea that Christ’s sacrifice was a gift from God to all those who would accept it and that “earning one’s way” to salvation wasn’t necessary, or even possible. The words resonated, perfectly contrasting old beliefs.

“At the end of his talk, he said, ‘if you would like to accept this relationship with Christ, stand up!’ And I stood up.” She wasn’t the only one.

But it turns out I was wrong in thinking Witt found God in the woods: “He was equally with me in my childhood church. It’s just that my heart was changed, my eyes were opened.” Now, she thinks she could return to that church—or anywhere else in the world—and be as close to God as she was while on the dock. Yale was the place where she managed to fill what she calls the “God-shaped hole” in her heart, but she doesn’t expect that it will ever be empty again.

I tell her that my heart feels, and has always felt, whole. She asks where I find happiness, if I don’t have God as an ultimate source of joy and meaning. “Any time spent with my girlfriend,” I tell her. “Optimism for the future. Interesting conversations with friends and strangers. The moment when a great piece of dance music hits its peak, which is probably the closest I come to how you felt in that room.” I pause. “Good food. Good books. Good company.” I look at her. “I think I have everything I need.”

She nods, but I’m not sure she believes me. I’m not sure I believe me. I tried talking to God when I was young and like millions of others, I asked for a sign. When I didn’t receive it, and some of them did, I thought I might have missed something. Was it possible that I was doing something wrong?

Even after the interviews, I’m still thinking about Fabian’s forgiveness, Aboutorabi’s moral pillars, Witt’s God-shaped hole. I haven’t been brought to God, but I’m acutely conscious that the age of nineteen is no time to decide I understand morality. There are limits to my ongoing search: I am a scientist, I’ve seen brain scans of Buddhist monks, I’ve studied the neurological basis of near-death experience. Using terms like “soul” and “grace” won’t help me advance in my field. But even if Christian logic does not persuade me, that’s no excuse to assume that converts are the ones wearing ideological blinders.

I ask most of my sources what they think it means for someone to seek but not find. Those who heard God’s voice—Witt, Fabian, a few others—tell me not to give up, that if I remain open to possibility, I might well hear something.

**

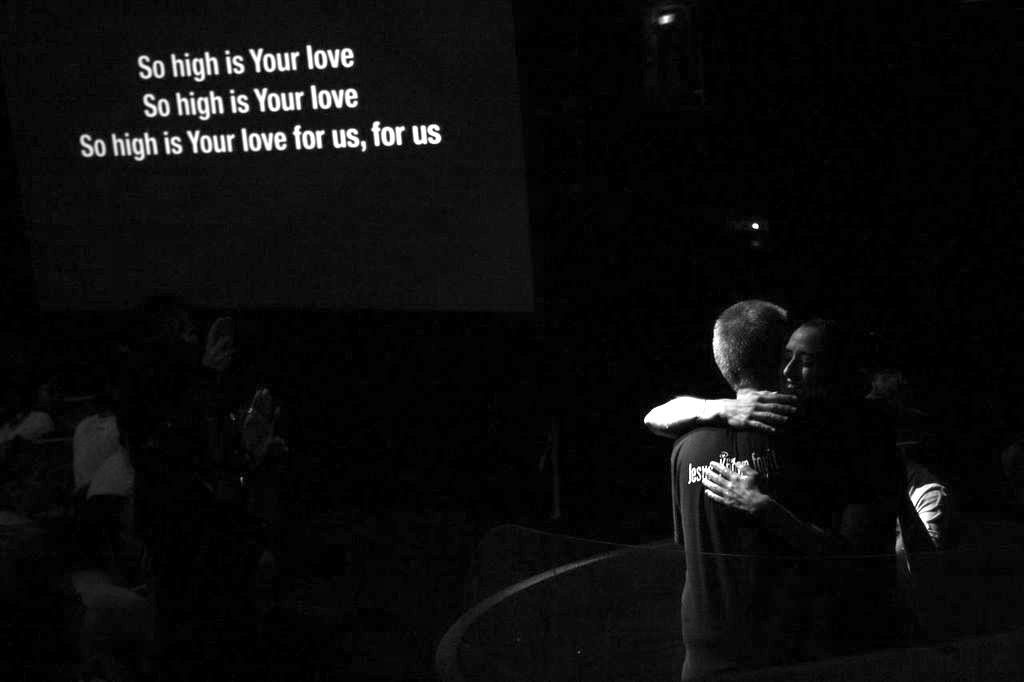

I’m standing in Toad’s Place on Sunday morning to watch Kim Fabian’s baptism. The church band plays catchy, original Christian rock; Witt, sitting on the bar beside me, sings along. When the music stops, the lead singer—Pastor Justin Kendrick—delivers a moving sermon on the meaning of baptism.

Music swells again as the first worshipper steps forward for a pre-baptism interview with Pastor Justin. Witt slides off the bar and rushes away toward him, saying, “I’ve got to be baptized. Bye!” She had just come intending to watch her friend, but the sense of religious urgency in the room drew her in, and even I’m beginning to feel it; my heart is racing.

Fabian takes a microphone and relates her story to the congregation: “I just couldn’t do it by myself. Without Jesus, nothing else was enough.” She steps off the stage, and is dipped into a blue plastic tub. Toad’s echoes with cheering and applause. Every member of the congregation stretches a hand in Fabian’s direction. She holds hers out to heaven.

Witt is next on stage. “I don’t know how to tell this story,” she tells Pastor Justin. “Words are just completely insufficient to describe the experience.”

For now, words are all I’ve got.

Aaron Gertler is a junior in Timothy Dwight College.