The card reader glows a prohibitive red. It is barely September, and Yale’s campus is poised on the brink of the new semester. The clusters of graduate students who will soon clog the front steps of the building, smoking their menthols or scraping at Styrofoam pad thai containers with plastic forks, are nowhere to be seen. Green Hall is still waiting for its occupants. Coming in from the hard light of Chapel Street at noon, I pass through double glass doors into the cool dark of the atrium.

The painting studios are on the second floor, and I take the stairs with a rhythm now familiar to me. Usually, most of these rooms are locked, but today the heavy metal doors are flung wide open. The whole place feels atypically loose, and peaceful. The soles of my shoes crack the quiet, sending an echo into the corridor as fluorescent lights flicker on to mark my way.

I note with satisfaction that Room 211, at least, is locked. I fish my key ring out of my bag and feel around for a thick brass talisman, with “AZHU” printed on its head. I know the right key by its weight in my hand, and the door unlocks with a familiar schhckk. Room 211 is empty—it’s the early days, still. The last early days I’ll experience here. I’ve come back to be comforted; I want the space to fold me back in. I need a constant, something I can count on.

The room is dead quiet and barely recognizable. Light streams in from the windows spanning the facing wall, and sets a bleached glow over the room. It looks unbelievably clean—like the walls have renewed themselves over the summer, shedding a mottled skin for a newer, glistening one.

After the door slams shut behind me, 211 seems more familiar. Stepping closer to the walls, I see faint evidence of the room’s recent past: paint that the summer maintenance crew has failed to totally erase. Here, a dripped line of red; by the window, a constellation of blue acrylic spattering that I can trace to a friend’s practice in the autumn of our sophomore year. The floors are a complex map of past work. The oldest colors have been scrubbed down into the concrete, losing all but the very last of their character. Other stains look just-spilled. I try to parse the blots of color for their associations—a distinctive purple that another friend is known to favor; that blood red, that time I cut my foot on a broken oil bottle and the blood went everywhere (and how it looked like paint).

The first semester of my freshman year, I enrolled in my first painting class in 211. I took to the rhythm of the studio immediately—settling in for multi-hour marathons, balancing my dinner on the radiator. It was a lonely semester, with few of the other students intending to be art majors. They came to class, they left. They didn’t seem to feel the gravity of the room so strongly. The next year, however, I found my people. We felt like pioneers, building our shelter in Green 211.

Zach was the owner of the blue acrylic constellations. I remember his glass palette, always spotless, his neat rows of small piles of paint, his paintings—small brown boxes against a blue grid, over and over again. His eyebrows, pinched together over wire-rimmed glasses, his skinny arms raised high, his fine fingers gripping the brush so hard that they turned white. I don’t remember him ever being happy with his paintings; I don’t remember any of us being happy with our paintings. That wasn’t the point. They’d hum on the walls, waiting for us, as we went about the other business of our weeks. The door swung open and shut, open and shut.

Now, as I stand in the middle of the room, any place my eyes rest is caked with memory. The dented gray radiators—spending the night here in winter, we huddled in front of the heaters on the cold floor, sleeping lightly, then rousing ourselves to finish the eight, twelve, twenty paintings due only hours later. That pink wing-back armchair (sagging more, now, than it used to) where we would sit when we had given up, however briefly.

To my left, the metal carts in which we stashed our lives’ trappings—artistic and otherwise. Teacups, warm sweaters, scented hand soap repurposed for brush cleaner. All the carts are imperfect in some way, whether it’s a missing wheel, a broken hinge, or a faulty latch. I know well the harsh screech of dragging the metal beasts across a concrete floor. Scraps of tape used to claim ownership, now effaced and cryptic: “racie,” suggests one, “CRAN,” shouts another. Thick gobs of paint can be picked off the surfaces like scabs.

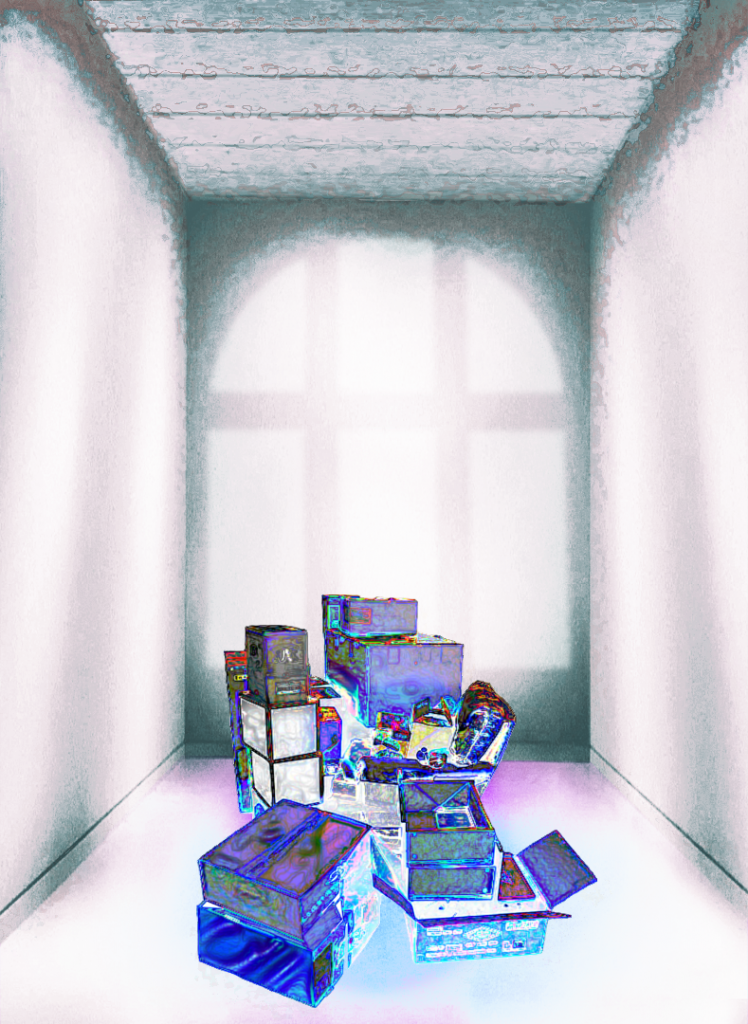

Looking out over the fresh glowing white of the movable partition walls, the neatly stacked (if visibly rickety) stools, it’s hard to believe how quickly it can all build up and be taken down. Effort, frustration, investment, paint. Can it really be as important as it feels? Felling the trees, clearing the land, building the cabin—only to be swallowed in a forest fire at the end of each semester.

That original wagon party finally reached the frontier and split to go their separate ways. Some people are making video work now; some are designers, some animators. Some have no idea what they’re doing after graduation this May, but they probably won’t be painting. As it pushes us out gently, the school gathers in a new batch of pioneers, preparing itself for their new architecture. We won’t be completely erased, though, and most likely, we will be back. We’ve kept our keys.