On November 26, 2012, twenty-five alleged members of two of the most violent gangs in New Haven filed into the Hall of Records, an imposing stone building with wide white columns on Orange Street. At the door, Reverend William Mathis greeted the young people, all of whom were on probation or parole. Those twenty-five were about to attend the first “call-in” of Project Longevity, a new police initiative that has come to exemplify the practical challenges even the most progressive anti-violence programs face.

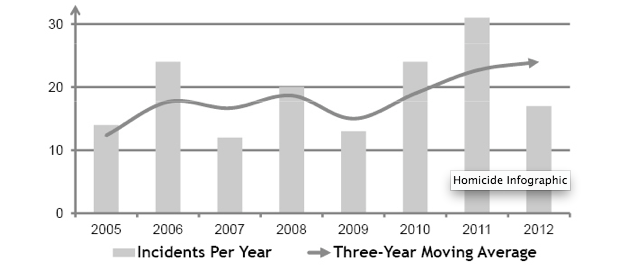

New Haven is a small city with a high homicide rate. Between 2003 and 2012, 185 people were killed in the city. In 2011, violence reached a twenty-year high, with thirty-four homicides and 133 non-fatal shootings. At the end of that year, the mayor hired a new chief of police, Dean Esserman, and gave him clear orders: stop the shootings.

Esserman already knew New Haven well. He had been the assistant chief of police in the nineties, when he helped institute community policing in every area. Cops walked neighborhood beats instead of driving in circles, gathered intelligence on gang leaders instead of petty criminals, and steered people towards social services instead of jail. In 1993, Esserman left for a job in New York. The department’s budget was cut and subsequent chiefs reverted to more traditional law enforcement methods, which saturated violent areas with police and racked up arrests.

Now Esserman is back, and so is community policing. In 2012, he helped launch Project Longevity, a program that, though widely praised, has left some in the community feeling unfairly targeted and unwilling to buy in.

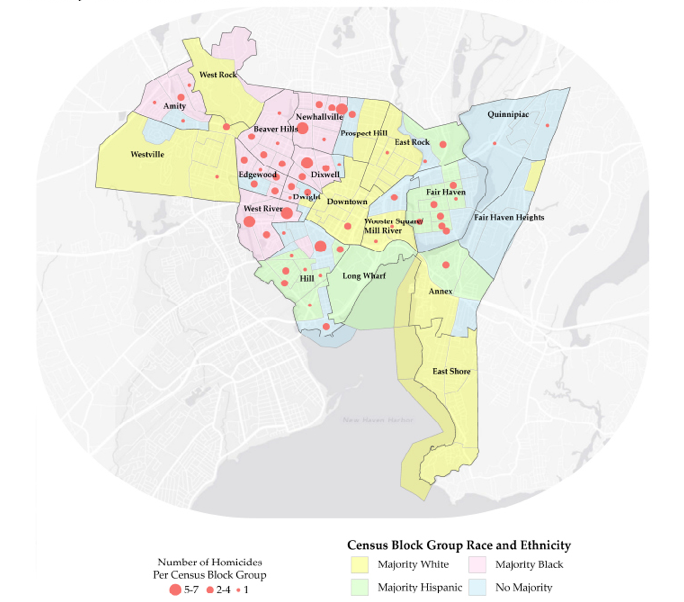

For eleven months before the first call-in, a team of cops, detectives, academics, and activists studied the perpetrators and victims of the worst violence in New Haven. Officially, these are “groups,” just a step or two above cliques, and not “gangs,” which are fairly established, with an internally-recognized hierarchy. The team went through five years of police records. They interviewed neighborhood cops, probation and parole officers, federal agents, and family members. They analyzed relationships between individuals. If you murdered Jim, they asked, who else was in the car? What was your relationship with Jim before the shooting? Who do you hang out with?

The cops used to just track down and arrest an individual in connection to a crime, but Project Longevity has expanded the scope of their inquiry. Police can react to a gang-related murder by focusing their attention on an entire network. And the police aren’t working alone—state and federal law enforcement have also promised to crack down on whole groups who do not heed Project Longevity’s message.

In November, Project Longevity brought in alleged gang members for a two-hour meeting. They displayed the initiative’s “table of organization” they had created over the past eleven months, a map of relationships that visually linked each person in the room. The team’s message was clear: we know who you are. We know who your friends are. The body count ends now.

“The first of you who goes to kill—we don’t just go after you,” Esserman says, summarizing his speech at the first call-in for me one afternoon in his office. “We go after all of you. You might not be responsible for the murder, but you are responsible for being part of the gang. Look to your left and look to your right—you are your brother’s and your sister’s keeper. What one does, the gang pays for.”

*

Project Longevity’s “focused deterrence” approach originated in Boston in the nineties with David Kennedy, now a professor at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York. In his book Don’t Shoot, Kennedy writes that the people committing violent crimes are “not an entire generation, not everybody in the hot neighborhoods, not all the young black men. Not everybody exposed to violent video games or rap. Not everybody from a single-parent family. Not everybody who could get a gun if they wanted one.”

Focused deterrence is based on a common pattern identified by criminologists: the overwhelming majority of violence in cities is caused by a very small percentage of the population that moves in identifiable groups. The opposite of focused deterrence is general deterrence—the “stop and frisk” program in New York City, for example, which was recently declared unconstitutional by a federal appeals court—where everyone gets police attention, whether or not they are violent offenders.

According to a 2009 New Yorker article, Kennedy began developing the roots of what would become the Project Longevity strategy in 1994, when the National Institute of Justice gave him and two colleagues a grant to study gang violence in Boston. Kennedy met Paul Joyce, the leader of a city police unit focused on gangs. Joyce had been quietly and successfully reducing homicides among some of Boston’s most violent gangs.

Joyce had realized that law enforcement officials and punitive measures alone couldn’t make people stop shooting. No matter how long prison sentences were, or how many young men got arrested, the number of homicides stayed constant. But if people with moral authority in the community—local clergy, grandmothers, and victims of violence—told violent offenders to stop shooting, they were more likely to listen.

Kennedy studied Joyce’s tactics for six months, eventually developing a framework for focused deterrence as a citywide program. Instead of asking cops to deliver informal notifications to individual gang members, Kennedy and his colleagues designed a forum—the call-in—where they identified members of gangs to come together and hear the clear message: if one member of a gang commits murder, the whole unit will be placed under a microscope. Five months after the first call-in, the homicide rate had gone down by seventy-one percent. People started calling it “The Boston Miracle.”

*

The first person I met who had been “called in” to Project Longevity, Sean, seemed to be a homegrown New Haven miracle. I was taking a sociology class called “The Urban Street Gang” with Project Longevity researcher and Yale professor Andrew Papachristos, who identifies gang members in New Haven and analyzes their links to each other. We learned about Project Longevity from four panelists: Reverend Mathis, the director of the program; Doug Bethea, a street outreach worker whose son was murdered in 2006; Thomas McDaniels, who founded a support group for grieving family members called “Fathers Cry Too”; and Bethea’s son Sean, a twenty-two-year-old convicted felon who was on probation and had been called in to one of Project Longevity’s first meetings.

Sean sat quietly at our seminar table while Reverend Mathis explained the basics of the program. Then it was Sean’s turn to speak. He told us that in 2009 he went to jail for robbery; he has since been released and is now on probation until 2015. His probation officer mandated he attend Project Longevity’s meeting. He has since moved out of his old neighborhood, he dresses differently, and he doesn’t hang out with the same people.

“I wanna change,” Sean said. “I don’t wanna die out here.”

The people in charge of Project Longevity are optimistic that there are many others like Sean who want to change, and who will change. Reverend Mathis said that the program will lead violent offenders to “life—and life more abundantly.” Attorney General Eric Holder gave a press conference in New Haven the day after attending the city’s first call-in and said, “Project Longevity will send a powerful message to those who would harm their fellow citizens.” Chief Esserman said Project Longevity will have a profound effect on the relationship between the community and the police because “the community—in the full light of day—sees us giving their children a second chance.”

As I learned more about the program, I found that the voices of one central constituency are absent from the media coverage. Where were the people who had been called in? What were they saying?

Reverend Mathis would not release the names of the call-in invitees, and neither would Professor Papachristos or Barbara Tinney, who leads Project Longevity’s social services. The formal avenues had failed, so I went to the street.

*

Kensington Street is a wide city street a few blocks west of downtown New Haven. Large white and beige houses with two-story porches are interspersed with brick apartment buildings and smaller row houses. At Kensington and Chapel, a steady flow of people enter Dux Market to buy cigarettes and lottery tickets, or stand by the curb to catch up with neighborhood friends.

The consensus among the residents I speak with is that Kensington Street used to be crazy. Asia and Joshua, who look about eighteen and are standing by a grassy park halfway down the street, say the neighborhood used to be so crowded, you could look to either side and only see people. Gus, a middle-aged man who works at Dux, says there used to be people selling drugs outside his shop in broad daylight. An older woman tells me in the eighties Kensington was “really rough.”

Everyone agrees that Kensington is calmer than it used to be, though the cause and timing of this transformation are up for debate. Some say it happened a year ago, when everyone got arrested; others say it happened eight years ago, when everyone got arrested. When I walk down to Kensington one afternoon, there are clusters of people sitting on stoops, hanging out in yards, pushing strollers, and leaning out of parked-car windows.

Laquanna Miller is standing outside her sister’s house, watching her two-year-old nephew Tramire. Miller remembers standing on the porch of this same house in October, when a drive-by shooter on Kensington accidentally shot Tramire in the chest. The bullet fractured his pelvis and caused citywide outrage. Today Tramire is grinning, wearing a blue sweatshirt. Miller’s son was called in to Project Longevity, and she has less than glowing things to say about the program.

“Basically, I don’t think it’s working,” she says. “Still people getting shot, still people selling drugs.”

Her criticisms are two-fold: first, by going through the probation and parole lists, the researchers and cops working on Project Longevity aren’t necessarily targeting people actively making trouble on the street.

“Just because you hang in the area doesn’t mean you’re in a gang,” Miller says. According to her, they brought in some young men who aren’t actively involved in violence, like her son, and they didn’t call in some young men who are. She seems uncomfortable with the basic premise of the program—that people should be accountable for the actions of their networks of friends.

Second, she has no idea what the program does or how it works. If they’re trying to bring the community together to help fight violence, she says this program isn’t a good way to do it. Her son, who shows up mid-way through our conversation, received a letter from his probation officer about the call-in. He didn’t know what it was about, and didn’t want to show up, but his probation officer made him. “I don’t even understand what Longevity is,” Miller says. “Is it for drugs, is it for guns, is it for both?”

Her son would not give me his name, and most people I spoke to who had been called in wanted to stay off the record. This, of course, helped explain why their voices were largely missing from the media coverage of Project Longevity. Because they wouldn’t give their names, it was difficult and often impossible to fact check their stories, or go back to them for more information. Their critiques lacked the specificity offered by the sociologists and police officers I spoke with, but ultimately, they were the ones with firsthand information about the experience of being called in.

Miller’s son says the program doesn’t actually give people the tools to change.

“It’s bullshit,” he says. He and other young men in the neighborhood were told to get off the streets—but no one can get a job, and, he says, the street is the only place to make a living. He thought the social workers connected to Project Longevity would get people jobs, but they haven’t.

“Us being from the streets, we don’t know if they’re pushing their power,” he tells me. His criticism challenges the basic trade-off proposed by Project Longevity—that the police will help you out with jobs and social services, if you’ll help them by not shooting. But to Miller’s son, the power disparity between the police and the alleged gang members is so wide that a give-and-take model just seems unfair. How could he trust police after years of watching them round up his friends?

The other Kensington Street residents who were called in to Project Longevity had similar criticisms. One young man in a red sweatshirt is angry about the infringements on rights. He says the cops are targeting whole groups of people for individual crimes, even when many of those targeted have nothing to do with those crimes. He says he’s not in a gang and he doesn’t want to be treated as if he is. The loose red sweatshirt he’s wearing now is the same one he was wearing recently when a cop stopped him and said he could go back to jail for wearing red, because this is a Bloods area. But he just got out of jail, he says, and he has to wear what he has. Another teenager says he isn’t a Blood, and he doesn’t understand why he was called in as an alleged member of the gang. A third young man pulls a Project Longevity business card out of his pocket, and says the call-ins weren’t useful because there was “too much police there.” The negative associations he had with the police were simply too strong to overcome in one meeting.

When I tell Chief Esserman that some participants feel like they are being wrongly identified as gang members just because they’re on probation and parole, he responds quickly and firmly.

“They’re bullshitting you,” he says. “We didn’t just call you in because you’re on probation and parole, because how come we didn’t call in ninety percent of everyone on probation and parole?” Esserman says the Project Longevity team did careful, precise research for the eleven months before the call-in. They went through five years of records. They did link analysis, creating maps of social networks.

When I ask if it’s possible that they’ve made mistakes, or misidentified people, he says, sure—

“That bullet could have gone into their body by accident when they were in the Yale emergency room, and the guy we arrested and convicted for shooting them could have been wrong, and the gun could have been make-believe and they could have been from Mars and they really weren’t the person who was dying in the hospital that day.” He looks at me as if I could not be more naïve.

He says his team is not “fishing,” that those called in were summoned for specific, research-backed reasons. They are not dragging a net down Kensington Street, looking for poor people or black people or people with a criminal record. “We’re doing the exact opposite,” he says. “We’re surgeons.”

And even as some of the participants in Project Longevity say the program is at odds with the community’s interests, there are also residents on Kensington Street who agree with the police’s crime-fighting efforts. Gus, who works at the corner store, tells me the neighborhood has changed for the better, and that “the police are doing a good job.” A young mother named Mary says community policing can be frustrating, but she’s also grateful for their vigilance, because she has a little girl.

“That’s why the cops are taking everyone,” she says. “’Cause we have to think of the children.”

Project Longevity isn’t taking everyone. But the main challenge for the police is that their surgical work can look and feel to everyone else like an arbitrary round-up of all the young men in the neighborhood.

*

Scot Esdaile, the president of the Connecticut NAACP, is one of the most vocal critics of Project Longevity. He grew up in Newhallville, another neighborhood whose gang population has been targeted through the initiative. He says he knows everyone in the neighborhood, and that the kids who were called in complained to him afterwards.

“The kids said, ‘Scot, they brought us in, they bought us pizza and soda, and all they did was threaten us,’” Esdaile recalls. Esdaile is frustrated because he says the program seems like it was simply imposed by law enforcement without considering the input of the community.

Reverend Mathis and Chief Esserman contend that they held a series of meetings with the community before they launched the initiative. They briefed local politicians, clergy members, and activists on Project Longevity, and asked particularly interested people to join the team.

The debate over Project Longevity raises the question of what constitutes “the community.” All the people I talk to are trying to speak for the community, either implicitly or explicitly: Scot Esdaile, Reverend Mathis, the New Haven Police Department, the residents on Kensington Street. But the community is heterogeneous, and in this case, it’s divided. Even if Project Longevity is a thoughtful, precise program based on months of data collection, there is still the challenge of making sure those affected understand the program and support its results.

It is much too early to tell what impact Project Longevity is going to make. The numbers in New Haven are small, and the call-ins only began a year ago. Its official evaluation will happen in three years, and will be conducted by Professor Papachristos and a team of colleagues. They will determine the success of the program based on whether there is a statistically significant reduction in shootings and arrests for violent crimes among the groups they’ve been working with. Papachristos’s research team meets weekly and tracks every single shooting that occurs within the city, to determine whether or not it was gang-related. The team hopes to steadily collect enough data to establish if Project Longevity is helping to stop the shootings.

*

One Sunday morning, I attend Reverend Mathis’s church service on Sperry Street, one block away from Kensington. The Springs of Life Giving Water Church is not large—it has only twelve chipped black pews in its center aisle—but it is lively. There is a full drum set and keyboard; the music is so loud I can’t quite hear what the fellow congregants say when we lean in to bless each other. Reverend Mathis wears a long black robe with red buttons. He wipes the sweat from his forehead as he delivers a spirited sermon and leads us to Hebrews 10:24: “And let us consider how to stir up one another to love and good works, not neglecting to meet together, as is the habit of some, but encouraging one another, and all the more as you see the Day drawing near.”

Reverend Mathis tells us that we must be encouragers for those around us who have lost their way. Seeing me in the audience, he adds to his sermon that Project Longevity is about encouraging the people who commit violence in New Haven to change their course; it is about showing them that the community cares about them, and is affected by them.

In Reverend Mathis’s view, as in Project Longevity’s view, we are all our brothers’ keepers. It is our job, as community members, or service providers, or police officers, to steer gang members towards the right path. It is up to those who can to prevent the man on his right from pulling the trigger, and to keep the man on his left from drawing a knife.

But whether or not Project Longevity succeeds in numerical metrics, a question remains. How can a program overcome a divided community and years of mutual mistrust between police and people on the street? When we discuss “community,” who is responsible for whom? There is an enormous gap between the people trying to provide encouragement and the people who are supposed to receive it. Even while Reverend Mathis and Chief Esserman and a host of other leaders encourage gang members to be their brothers’ keepers, many of the participants in Project Longevity don’t agree that they are brothers. They do not want to be kept.