Exams were approaching, and Lauren Canalori, a literacy coach at Fair Haven School, was apprehensive. In a few weeks, her students would be taking a new round of standardized tests, the Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium (SBAC). It was April 2014, and the tests would measure how well the district’s Common Core curriculum, implemented over the past three years, was working. Canalori had helped develop the curriculum and train teachers to execute it; now, her efforts would be put to the test. On the untimed examination, students in grades three through eight would have to tackle fifteen to seventeen questions, which would take an estimated two to four hours. Canalori’s own son would be taking the exam as well.

“He’s a really strong student, he’s a thinker, and he’s going to struggle on the test,” she said, after discussing the sample questions she’d seen. Bookshelves surrounded the round table at which she sat, in a small chair intended for a middle schooler. The brightly lit library was quiet after students had left the weekly lunchtime tutoring session.

The Common Core, one of the largest and most ambitious education reforms in the history of the United States, is an Obama-era project that replaces statewide standards in reading and math for kindergarten through twelfth grade with national standards. In 2009, experts across the nation wrote the new guidelines, aiming to reduce the dramatic variation in standards from state to state. While the federal government does not force states to adopt the Common Core, it provides additional funding for those that do, and forty-three states have decided to make the switch.

The New Haven test results will be released in the next six months, and teachers, parents, and students are all unsure of what they will look like. In New York State, where Common Core testing was implemented in the spring of 2013, the first tests were so difficult that they brought many students to tears. In some New York schools, as many as eighty-five percent of students failed, according to The New York Times.

The standards, which expect first-grade students to “identify who is telling the story at various points in a text” and fifth-grade students to “graph points on the coordinate plane to solve real-world and mathematical problems,” are not a curriculum in themselves. However, they do provide a classroom framework for educators.

In Connecticut, New Haven was one of the first districts to embrace the standards. Students and teachers have spent the past few years adjusting to a Common Core-aligned curriculum. And while educators hope that the city’s head start will show in the test results, opinions on the new standards are mixed.

***

When Carlos Torre, a member and former president of the New Haven Board of Education, talks about the Common Core, his voice is calm. He sounds like a lawyer explaining the facts of a case he knows he will win. And he feels that the Common Core standards are a key step in moving American education forward. “It’s the first attempt in this country to have anything that resembles a national conversation about what our students should be able to know, understand, or do,” he explained.

Architects of the Core, along with their supporters, think that every American child should be taught how to think critically rather than spend time memorizing formulaic strategies for taking standardized tests. That means that teachers will have to make fundamental changes in the way they teach. But they do have the new guidelines to point them in the right direction. For example, reading and writing are now supposed to take a more central place in every class.

“When you start to become departmentalized in the older grades, teachers start to become very territorial about what their content is and what they do,” Canalori said. “[But] the Common Core says very clearly that everyone is a literacy teacher.” To make that a reality, she is helping her colleagues understand how best to teach different kinds of writing across subject areas. Now, in science class, students learn argumentative writing based on observations of experiments, while social studies lessons include persuasive writing based on data collection.

Under the Core, students also need to be able to read and analyze a wider variety of literary genres, and the Fair Haven School’s library shelves show it: Both nonfiction survival narratives and Sharon Draper young adult novels exploring the lives of urban teenagers expose students to a variety of genres and satisfy Common Core requirements. In math, Howe said, students develop a stronger sense of numbers, acquiring a more intuitive understanding of how, say, place value works. They focus on fewer concepts, but delve more deeply into each one.

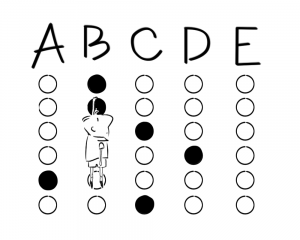

Before the Common Core, Canalori says, teachers often gave students “formulas” for answering different categories of questions on state assessments. “We have all these passive learners now. I think that the Common Core is going to take that away, because we don’t know what the kids are going to be asked,” Canalori said. In the past, teachers knew what type of essay their students would be asked to write: Fourth grade wrote narrative, fifth expository, seventh and eighth persuasive. Now, the test is unpredictable. Students need to be trained in many different kinds of writing, because the old formulas will not work on test day.

Canalori knows that that these tests are going to be a challenge. “The test is really hard. I firmly believe that teachers should have high expectations and that children rise to the expectations you set for them, and I’ve lived that in my career as a teacher. But the test is really difficult and I personally wonder if it’s developmentally appropriate.”

The already-difficult tests, she says, are made even tougher by the fact that they are taken on the computer. When I visited her at school, her students were busy practicing their computer skills, clicking away on desktops in the school library, building websites based on what they’d read about natural disasters. “I worry about their personal tech skills, but also I worry that we are somewhat behind in our technology infrastructure in the building and now we’re kind of running to play catch up,” Canalori said. Some schools simply have better equipment: Her son’s school in the suburbs supplies every student with an iPad, integrating technological literacy into everyday activities, but in Fair Haven, computers are often older models. But that’s changing: The school has received donated computers, and a state grant is helping schools across the New Haven district buy thousands more, largely intended to help students take the tests.

Marlin Coon, a sandy-haired student at the K-8 Worthington Hooker School in East Rock, took the test last spring, at the end of his third-grade year. He found that it was a little harder than tests he had taken previously, mainly because of the technology component. “I didn’t know what all the keys were. Plus writing is much faster than typing,” he said, swinging his legs while sitting next to his father at a local coffee shop.

Parent Dave Coon, PTA president at Worthington Hooker, voices a different concern. He and his fellow parents are worried that excessive testing will negatively impact their children’s education by forcing teachers to spend instructional time coaching students for tests. And, at Worthington Hooker, where Coon’s two sons attend school, testing occupied the school’s computers and shut down its library for two months.

Many parents report that even homework doesn’t look like it used to.Carol Boynton, a second-grade teacher at Edgewood School, said that many parents, unable to understand their children’s homework, have asked her what’s so terrible about teaching math the “normal” way. She recognizes that these new standards cause anxiety for parents. “I see a lot of frustrated parents reacting,” she said. “And I understand that.” She tries to explain that “some of this [material] has been around forever. It’s not really new. It’s just being formatted in a new way.”

***

Roger Howe, a Yale math professor who helped design the new standards in math, explained that the national standards are just that—standards. While the tests are administered nationwide, states and districts are left to design their own curricula. That asks teachers to completely rethink the way they plan their lessons. Despite all the work he and others have put into the structure of the Common Core, Howe noted that “standards and implementation are just two completely different things.”

New Haven is used to tackling big problems in education reform. In the early nineties, both Connecticut and Massachusetts raised teacher salaries and educational standards. They both had had similar scores on a standardized test called the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) in the eighties, and their math scores for fourth graders in 1992 were identical, both showing a jump in scores. But, unlike Connecticut, Massachusetts took an ongoing approach to reform, according to Howe, continually tweaking curricula and standards. Today, Massachusetts’s fourth graders rank second in the nation, while Connecticut’s hover around twentieth place.

This time, however, New Haven may be a bit ahead of the curve in preparing for the new standards and the associated testing. Three and a half years ago, the New Haven Unified School District replaced the previous math curriculum with Singapore math, which emphasizes independent problem solving to guide students towards discovering concepts and formulas instead of memorizing them. And two years ago, they introduced the reading curriculum designed in part by Canalori. In this sense, Common Core standards aren’t so new after all, and New Haven’s classrooms are already moving in the right direction. “It’s new for the rest of the state, it’s new for most of the country…but it isn’t for us,” Torre said.

This early adaptation sets New Haven apart from other states and districts because it has given students, and most importantly, teachers, time to adjust to and understand the new methods. Howe believes this head start has prepared New Haven students “in a pretty significant way,” making the difference between a successful rollout and a failed one.

***

But every teacher, in every classroom, in every school, still needs to be prepared to meet the standards. “The essential thing for the Common Core, or really any kind of curriculum innovation, is that you have to make sure teachers are ready to do it,” Howe said. “And this is what the U.S. education system chronically fails to do.” A survey conducted by Education Week in October 2013 found that teachers spent fewer than four days in Common Core training for both subjects. New Haven is hardly an exception and does not have many programs in place to provide teachers with opportunities for professional development and training to teach the Common Core.

The most promising program available—the Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute—is facilitated and funded by Yale, rather than by the city or the state. The seminars, which work with teachers to develop innovative curricula that they then post online, target Common Core strategies, because that’s what teachers are most interested in learning about. But they are not certified by any overseeing organization.

Founding Director of the Institute Jim Vivian sees teacher support as a weakness of the rollout both nationally and in New Haven. He knows that his workshops only reach a handful of teachers, and even the lesson plans that they produce and publish for free online can only provide so much support. He worries that not enough similar programs exist to support teachers through the transition process.

Boynton attended her first seminar at YNHTI in 2007. She continues to attend the program and use the online resources, and she encourages her colleagues to do the same. “It’s what we need as teachers. It’s an experience that teachers can have that will provide them with the tools they need to approach the Common Core,” she explained.

***

At both Fair Haven and Edgewood, students and teachers await results from the pilot round of SBAC testing. Scores from the pilot will not be used to make decisions about individual students’ placement or performance, but they will provide a general indication of how the district might perform once the final version of the test is administered next year.

Boynton feels a little more hopeful about the results that Edgewood School will receive this year. It was one of a few New Haven schools that participated in an earlier round of SBAC pilot testing in 2013, and her answer suggests that the tests are not to be feared. “Because we’ve been ahead of it a little bit, we’ve done it, we know a lot about what has to occur— not everything, but we have some ideas. I don’t think the anxiety is as high as it is in other places.”

Educators hope the Common Core standards will better serve their students. But, ultimately, many encourage their students to look beyond the test. “I work at a school where the philosophy is that you are much more than a test score,” Leslie Blatteau, a high school history teacher at Metropolitan Business Academy, said. “We want students to demonstrate creativity, innovation, collaboration, problem solving, analysis, citizenship—all these things that involve much more than sitting down at a computer.”

Caroline Sydney is a junior in Silliman College. She is an associate editor of the New Journal.