Emma picks me up from my dorm at Yale on the first day of spring break so she can drive me to her dorm at Wesleyan, where I plan to spend the next two nights to figure things out. She looks strange in the driver’s seat, taller and calmer than I’m used to, or maybe I’m just not used to the idea of her sitting there.

I still don’t know how to drive. Last summer I was supposed to learn, and the summer before that, and also the summer before that. I can’t convince myself that driving is any more critical a skill than juggling. It just seems like another way to be lonely. Lonely is how everyone looks in the photos on their licenses, which is an effect of being told not to smile: caged by the camera, stoic and solitary. On Emma’s license, earned when she was seventeen, her lips are pursed to hide the orthodontic metal reining in her wayward teeth. Now I see a glint on her nose, a tiny silver hoop. She sees me looking: “It’s new.”

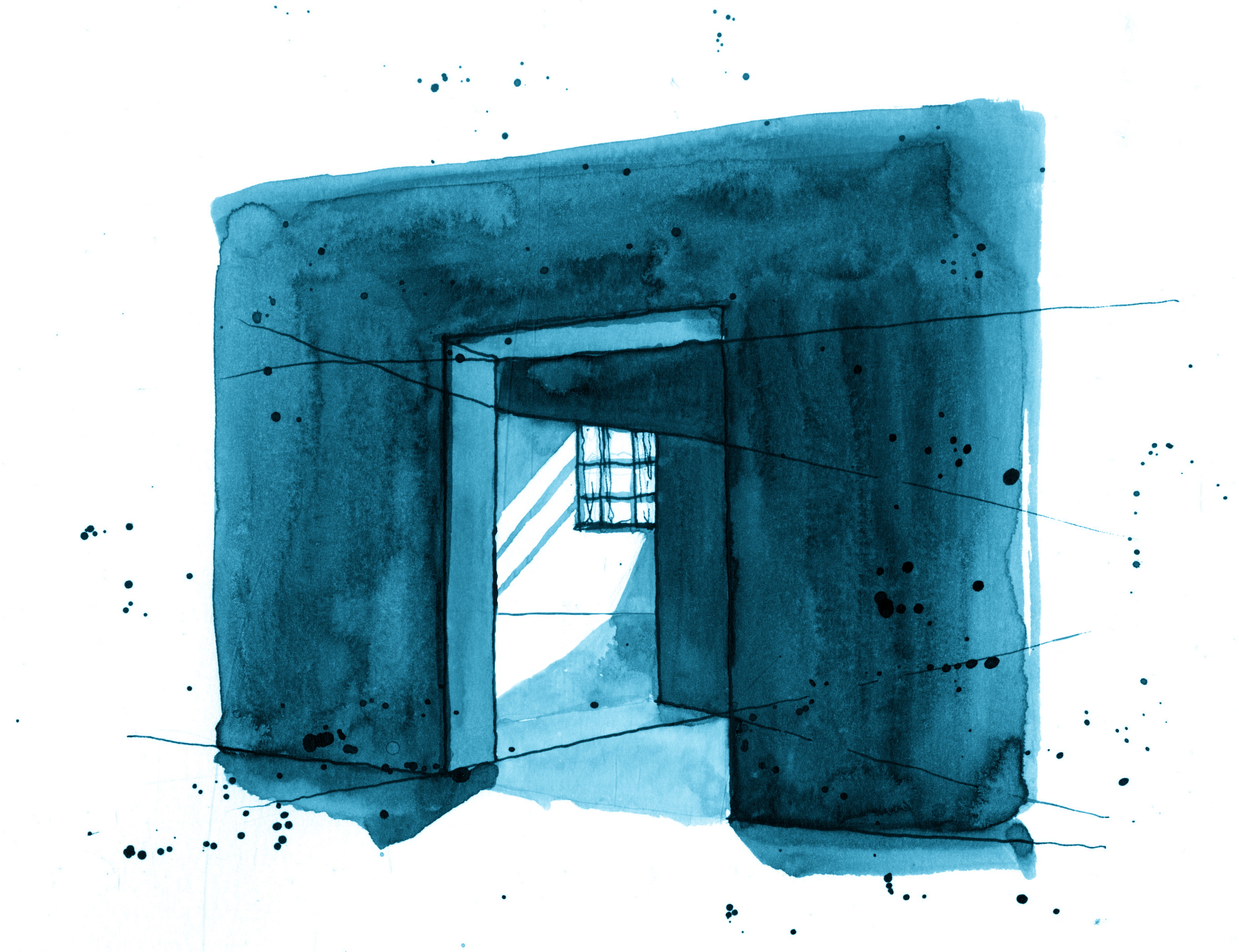

When the machine sputtered, I patted it as if I were consoling a child. From beneath the glass snuck bursts of light that I thought were trying to tell me something.

For dinner we go to an expensive Spanish restaurant where there won’t be any students and order a fourth of the sprawling tapas menu. When we’re splitting the bill I think suddenly about what my dad is always saying, that Emma’s father is a doctor who could afford to buy our entire neighborhood and still have change for pizza, and how that’s probably not true and anyway it’s a bad thought to think, but I can’t help that I’ve thought it.

In the car I realize I wasn’t even all that hungry, just tired. I was up until 4 a.m. scanning other people’s writing into an online database for a writing contest, crouched beside a finicky, old, all-in-one printer with hundreds of pages to go. The overhead light was dim, and my roommate had inexplicably packed up all the lamps, so I worked in the dark. Everyone I knew had left campus. When the machine sputtered, I patted it as if I were consoling a child. From beneath the glass snuck bursts of light that I thought were trying to tell me something.

I wasn’t supposed to be looking at any of the submissions because contest staff were to remain impartial, but of course I read everything I happened to see as if it were addressed to me. The last story was eighteen pages about a father and his son, who is a musician. The dedication, at the top of one cream-colored page, read “For Charles.” I wondered if Charles knew about this story, and if he did, whether he enjoyed it, or if he was put off by how self-consciously constructed it came across. But when I reread it imagining I was Charles, I was moved.

Emma is an English major, like me, except she wants to be a doctor, unlike me. She spent the last semester abroad in Dublin taking courses on medieval British literature because the upper-level courses on Joyce were closed to transfer students. In Dublin, she met Mason, who is taking some time off from art college in Tennessee to engage more fully in his jazz death metal band. When I hear this, I nod convulsively to show her how open-minded I have become. She doesn’t have any photos of Mason, only photos of her taken by him on her phone. They’re all black and white. She’s sitting on a brick wall strewn with graffiti, looking at the camera, at him, and now at me, sort of.

My mother, Susan, is a Chinese woman whose ability to find and befriend other Chinese women, including Emma’s mother, Shirley, will one day be revealed as an advanced form of echolocation.

Emma pulls into the parking lot next to her dorm, a stout building in beige. She’s a good driver, and fits her car into a tiny space like she’s threading a needle. Then she shuts off the music, this thrashing electronica that she’s kept muzzled at a low volume. “We can go up, then I’m going to pick up my weed,” she says, yanking the key out of the ignition. The heat in the car lingers, but I feel the incoming cold even beneath my down jacket, two sweaters, and the last t-shirt in the clean pile, which I received at the conclusion of my high school AP United States History class and reads “Four Score and Seven Assignments Ago…”

“You can come if you want,” Emma adds, as an afterthought.

We enter the building through the trash room and climb the stairs to her third-floor suite, where she lives with her friend Claire. Emma lets me in and goes off, saying she’ll be back soon. In the meantime I turn on the lights and go into the kitchen, where I open all the cabinets and drawers one at a time. Between Claire and Emma there are ten mugs, two handfuls of ornamented forks and spoons, and one slim knife. Inside one cabinet I find twelve types of tea, several of which are labeled “for women.” I decide on a cup of Women’s Chai. I press the home button on my phone repeatedly—I like to see it light up—and wait for the tea to boil.

I’m going to study her when she comes back. I’ll inspect her eyes, and watch her person for a smelly pouch or a plastic bag. But her hands are empty when I see her; her jeans don’t even have any pockets. She goes into her room and tells me she has to get some reading done. “It’s only the first day of break,” I say. Already, she’s with Persuasion, wrapping herself in blankets.

My mother, Susan, is a Chinese woman whose ability to find and befriend other Chinese women, including Emma’s mother, Shirley, will one day be revealed as an advanced form of echolocation. Susan and Shirley met in line waiting to pick us up from the first day of first grade. At Emma’s house, Susan and Shirley drank tea in the dining room while a floor below Emma and I decided we liked each other over a tub of one thousand Legos. That’s how friendship happens when you’re smaller: you presume it. The older you get, the longer it takes to be sure that someone is on your side. I’d call most of my earliest acquaintances “elevator friends.” These are people you’d never meet if it weren’t for repeated happenstance in intimate spaces, until one day you’re trying to call your house and you call their house instead.

The older you get, the longer it takes to be sure that someone is on your side. I’d call most of my earliest acquaintances “elevator friends.”

When we were smaller, Emma wasn’t allowed to bring her toys upstairs. We spent most of our time playing in the basement, where I accidentally broke a lot of things. Worst of all was a scale Lego model of Dumbledore’s study that took her weeks to build. She didn’t seem angry, but she refused to let me put the pieces back in order. “Everything you touch, you break,” she said, pressing a yellow tile into the place it had been moments ago. That’s not true, I protested. It was a little true. Once I was alone in her basement inspecting a paper model of an ornate Chinese junk when one of the sails broke off in my hand. I was so surprised and upset I almost yelled. But I didn’t want to her to discover what I had done, so I kept quiet and buried the pieces in a crate full of books beneath her desk. Why did people bother making things if they were going to break?

Emma’s silky lavender blanket is bunched around her knees. I haven’t brought anything to do, so I sit in her chair and open the small black notebook I carry around to a clean page. I’m in an introductory fiction class and have a story due the week after break. On Emma’s desk is a photocopy of E. M. Forster’s Aspects of the Novel. Chapter Three: Plot. “‘The king died and then the queen died’ is a story. ‘The king died, and then the queen died of grief’ is a plot.” A story, Forster writes, makes you ask “And then?” and a plot makes you ask “Why?”

I’ve been considering writing about a florist who has ceased to leave his shop and lives surrounded by overgrown houseplants. He makes his final sale, a bouquet of gardenias, to a woman who has axed her way through the shrubbery. Once he loved her. Then he suffocates on a daffodil. “And then?” “Why?” I get distracted. The snow starting outside seems unnecessary. There is already enough of it, these stout mounds brooding around the edges of Emma’s building like they’re waiting to be invited in.

At around 9 p.m., a girl enters without knocking and paws through Emma’s sparse wardrobe. The three of us go downstairs, where five of Emma’s other friends are already sitting knee-to-knee in a circle on Hannah’s small floor planning their road trip to Buku, which I learned earlier is a music festival in New Orleans. There is a tie-dyed dreamcatcher the size of a pocketwatch dangling off a hanger in Hannah’s open closet, the sort of thing you buy at a street fair and forget about.

Why did people bother making things if they were going to break?

In one trip scenario they’re going to spend a night in Atlanta and a night in Nashville on the way back. In another they’re staying a day in Houston, two days in New Orleans instead of one, and eating dinner with Martin’s sister in Richmond. At one point Martin has tacked on an extra ten hours to their driving time with the addition of a stop at the Mexican border. “Martin,” Emma says, after which her friends laugh and drop the idea. She’s only lying on Hannah’s bed looking at her phone, but she’s definitely the one in charge. The group sticks little red circles across the map like they’re spreading a pox. Around midnight Emma says she’s had enough and we decide it’s time to leave.

After Emma falls asleep, I go for a walk around her hallway and find a place to pace between the balcony and the vending machine. My phone starts vibrating. I see Home calling and don’t pick up. It’s my mom. She wants to know where I am. No one I know knows where I am, except for Emma. I like it that way. Every year I tell myself I’m not going back, and every year I hate myself for walking in the front door, taking off my sneakers by stepping on their backs the way my high school track coach said you’re not supposed to—it’s bad for your ankles—and taking my seat on the living room couch like it’s been reserved for me. I lean really far over the balcony, which is about a story and a half above the laundry room, and think about being reckless. If people were looking for me, where would they look first? Bang on my door, then check the library, the classroom I study in and have privately dubbed “A Room of My Own,” the coffee shop where I and a thousand other people have spent their time.

I’m pretty bad at hide-and-seek. I was tall long before the other kids in first grade were tall, which made hiding behind even the highest chairs or play castle walls difficult. So I sought walk-in closets, cabinets, once even a narrow pantry crammed with Italian herbed tomatoes, which made me feel like I was in a cave of little hearts. I wondered what would happen if I fell over this ledge and when Emma would realize, if it would take minutes, or hours, or the terrifying possibility of a year. And I wondered why the people we care about don’t just somehow know when bad things have happened to us without us having to tell them, why that’s not a sense anyone thought we needed to have.

“Jenny,” I hear. My mother; I’ve picked up. “Where are you? Is it snowing where you are? It’s snowing here.” We’re both quiet, like we’re stopped at a light and waiting for the other to go. “The snow looks like flour,” she says. “Someone had an accident in the kitchen if that’s true,” I finally respond. “That was a joke,” I add, when there’s silence.

I lean really far over the balcony, which is about a story and a half above the laundry room, and think about being reckless.

The snow really does look like flour. I’m looking out the window next to the balcony where you can see the snow falling. That big, innocent backyard. “Where are you?” my mother asks again. “Are you coming home soon?” She misses me. She says she misses me every time she looks at the snow. I don’t tell her I’m coming home. I haven’t decided if I will yet, but in three days I’ll be back on my parents’ couch.

The next morning Emma drops me off at the shuttle stop going back to Yale. We hug and I tell her to keep in touch. While I wait, I listen to other people calling their doctors about appointments. Hi it’s Jane, Hi it’s Matthew, Hi it’s Duncan, just confirming for Monday, Wednesday, Thursday. I wonder if any of the calls are serious, if anyone might have cancer or a grandmother dying, and I feel immediately guilty.

It’s cold outside, and I don’t get back until late. I unlock the door to my room and switch on the overhead light. As usual it does not turn on when requested, but takes its time, sliding into brightness. When it finally does turn on, the light is ungenerous, showing me everything exactly as I left it.