In October 2021, the Atlantic ran a piece about Alden Global Capital’s ransacking of the American press. A pioneer in what has been called vulture capitalism, the Manhattan-based hedge fund had purchased the owning company of the Chicago Tribune in May of 2021. At the time of sale, Alden already owned roughly two hundred newspapers, many of them small-town publications that the fund proceeded to ruthlessly gut. With its recent purchase, Alden added to its spoils the Chicago Tribune, the Los Angeles Times, the New York Daily News, and six other publications. Two days after the sale, the staff of the Tribune, a quarter of whom wereas immediately laid off, was put to work in an obscure corner of the city. “Here was one of America’s most storied newspapers—a publication that had endorsed Abraham Lincoln and scooped the Treaty of Versailles, that had toppled political bosses and tangled with crooked mayors and collected dozens of Pulitzer Prizes—reduced to a newsroom the size of a Chipotle,” reporter McKay Coppins wrote.

Alden’s buyout of the Tribune was just one crisis in the long conflict between capital and journalism. New Haven provides an illuminating case study. Included in Alden’s deal for the Tribune was a much smaller paper, New Haven’s very own Advocate—or at least a mutilated remnant of it. Founded in 1975 in an attempt to break out of the confines of the corporate newsroom, the New Haven Advocate went through a long series of buyouts until it was dissolved into CTNow, a weekly aggregator of arts and culture events in the state. When Alden purchased the Tribune Company, the relatively obscure CTNow was part of the deal.

How did the Advocate, a paper inspired by the anti-capitalist leaflets that nineteen-sixties stoners stapled together, end up absorbed by the conglomerate-behemoth Alden? The basic timeline is simple enough. In 1999, Advocate founder Geoffrey Robinson sold the paper to the Hartford Courant. The following year, the Courant’s parent company, Times-Mirror, was purchased by the Tribune Company for eight billion dollars. In May of 2021, Alden bought the Tribune company. Somewhere in the debris lay the disfigured corpse of the Advocate. Born in protest of to the atrocities of American capitalism and the lies spun by the mainstream media, the rebellious spirit of the Advocate would have to find a new home.

On an unseasonably warm day in late November, I walked east past the northern edge of the New Haven Green to learn more about the history of the Advocate. Afternoon threatened to turn into evening, and the setting sun caught the season’s last orange, yellow, and red leaves. Initially, I struggled to find the building I was looking for—51 Chapel Street, the current home of the New Haven Independent, a locally-rooted non-profit newspaper that publishes exclusively online. Finally, I spotted 51 in bronze lettering. The entryway sat between a high-end hat shop and Ferucci’s, an independent dress clothing es store. The block looked like it was frozen in the nineteen-fifties; as I crossed the street, I wondered if I might run into a twenty-year old Leonard Cohen.

Up three flights of stairs, I found someone who came close enough: the Independent’s editor and founder, Paul Bass. Wearing a yellow t-shirt, a colorful yarmulke, and blue jeans that might generously be called fatherly, Bass carries himself with a humility that obscures his importance in New Haven’s journalistic landscape. As I sat in his office and snacked on cannolis, Bass treated me to an hour-long history of New Haven journalism. He walked me through how a beloved, city paper, anti-establishment to its core, inspired by anti-capitalist leaflets of the nineteen-sixties was ultimately purchased by the vampires at Alden.

‘We couldn’t help but make money’

Before Bass became the editor of the Independent, he wrote for and edited the Advocate. The paper was born as an alternative to the straight-laced newsroom of the Hartford Courant. However, the Advocate had its roots in what is now called the underground press of the nineteen-sixties. Exposure to the brutalities of Southern racism, the escalating war in Vietnam, and, most of all, the mandatory draft, fueled for youth of that generation a rage at establishment institutions—schools, government, newspapers—that no mainstream publication could temper. The underground press was given its name for its promotion of drug use and legalization, but it was equally marked by a rebellion against the lies of American capitalism and their dissemination in major U.S. newspapers.

To better understand the counter-cultural presses of the nineteen-sixties and seventies, I spoke with Jim Sleeper, a retired professor of political science at Yale (and a former writer at the New Journal) who worked as a journalist in the nineteen-seventies. His baritone voice carried smoothly over the phone. He had a confidence and meter to his speech that reminded me of my grandfather, but instead of telling me stories about the lessons he learned in business school or his memory of the founding of the state of Israel, Sleeper’s stories centered around his time in the nineteen-seventies counterculture.

Sleeper recalled his time as a graduate student at Harvard in the mid nineteen-seventies, when he would line up on Wednesday nights to pick up each week’s issue of the Village Voice, a paper born out of the same frustration with the mainstream press that helped birth the Advocate. By the nineteen-seventies, the rebellious spirit of the previous decade had partially dissipated, but an appetite for news sources that rejected the inanities of the corporate press remained. The papers born from this nineteen-seventies transition period—the most famous of which was the Village Voice—are now referred to as “the alternative press.” These alternative weeklies retained much of the rebellious spirit of the previous decade but were run like small businesses.

The Boston Phoenix, which Sleeper wrote for, was one of these alternative weeklies. The Advocate, for its part, was founded in 1975 by two copy-editors at the Hartford Courant who, in Bass’ telling, were bored by the articles their paper was publishing.

“The hippies and druggies were coming above ground in their lives,” Bass told me. “They’re buying homes, making a little more money. And I think the new alternative press reflected that. They were still anti-military, they were still critical of the establishment, especially the media, and they were very pro-drugs, but they were more above ground and they made their money from restaurant ads and sex ads. Especially sex ads.”. (In a eulogy for the Advocate Bass wrote in 2013, he quotes a friend asking him, “Don’t you feel like you’re wrapping the Talmud around a copy of Hustler?”)

I asked Bass how publications like the Advocate managed to retain their spirit of rebellion and independence while meeting deadlines and generating enough income to stay afloat. Bass assured me there was never a problem—the alternative papers were beloved, and the mainstream press was loathed. “Even if the people running these papers were stoned out of their mind, forgetting to pay the electricity bill, they couldn’t help but make money,” Bass said.

One of the hallmark features of the independent press of those years was the writing style known now as “New Journalism.” In the underground and alternative press, commitment to objectivity—a staple of the mainstream press—was seen as nothing but the mainstream media’s veneer for the corporate agenda that their papers pushed. “Capitalism is good, corporate profits are good for the economy,” Bass told me, mimicking the one belief that mainstream journalism was not supposed to question.

New Journalism embraced a different philosophy. “You brought tools of fiction to how you write,” Bass said. “You develop character, you always make a point, and you don’t pretend to be objective.”

To Bass, the Advocate’s great popularity stemmed from the paper’s willingness to challenge the established norms of the day—drug culture was promoted, slumlords were exposed, private property was questioned. That, and they knew where the best restaurants were. “Even though the front of the book was the news and the investigative pieces, people of all backgrounds counted on it to know where to go out and have fun, wrestle with ideas about culture. It was fun, it was controversial, it was wild.”

But the paper’s days of youthful rebellion did not last. By the late nineteen-nineties, alternative weeklies “were making so much money, and their owners were getting older, that all over the country, big companies, mainstream corporate newsrooms, were buying these weeklies because they thought they were cash cows,” Bass said. In 1999, satisfied with the success of the paper he created, Advocate founder Geoff Robinson sold the paper to Times-Mirror, a major media conglomerate and the parent company of the Hartford Courant—the paper Robinson and his colleague Edward Matys had abandoned in order to found the Advocate. Business-savvy as they may have seemed, the new owners “didn’t have the DNA of those founders, they didn’t exist to challenge established norms,” Bass said. These new owners were interested in cash and cash alone. To Bass, it was no surprise that the paper eventually tanked.

Mark Oppenheimer, now a lecturer in Yale’s English department and coordinator of the Yale Journalism Initiative, served as an editor of the Advocate from 2004 through 2006. “By the time I got there, you could no longer show up to work,” he pauses, “on substances. I think there was probably too much fear of lawsuits.”

Oppenheimer still found the Advocate a welcome change of pace from the Courant. Compared with the three- hundred- person newsroom at the Courant, the Advocate had a staff of roughly ten. “It was more like being part of an elite strike force, instead of having a boss, a deputy boss, and all that bureaucracy,” Oppenheimer said.

The death of local newspapers, and the struggles of contemporary journalism, are frequently blamed on the internet. Prior to the internet, a venue like Toad’s would have relied on advertising in papers such as the Advocate to reach their desired audience. With the rise of the internet, however, local businesses no longer needed the Advocate to reach their audience. The loss of ad revenue created a problem for the papers. Nevertheless, Bass insists that the issue that actually felled the Advocate and similar papers was much simpler: they weren’t interesting anymore.

By the late nineties—once the Advocate had been bought by Times-Mirror—alternative weeklies were owned by “boring, corporate types—their main concern was not getting sued,” Bass said. “So, if you wrote a lede and it totally sucked, your editor would say, ‘What a great lede—how can we make it better?’ even though you misspelled everything and it was total crap.”

Unlike these papers, the New Haven Independent, founded in 2005 and published exclusively online, has remained free of corporate influence and, according to its editor, Bass, is committed to staying that way. Despite the inroads the corporate media has made into independent media in the past four decades, Bass remains confident that the Independent of today lives up to the best values of independent journalism.

“I find that with the Independent—I’m closer with my readership, I have the most diverse readership I’ve ever had, and it costs the least,” Bass said. “The ability to challenge corporate control and do independent media is by far greater than it’s ever been. The alt-weeklies were nothing compared to what’s around now.”

From perusing the Independent’s website or spending an afternoon in their office, no one would guess the paper’s roots in the alternative press. Today, Bass’s hair is short, and his office has an atmosphere of middle-class professionalism. A twenty-year old looking to rebel would do better to trip acid and burn an American flag than intern at the Independent. But, if today’s Independent might disappoint adrenaline-seeking college leftists, that’s not particularly surprising. It’s been forty years since Bass was twenty.

Connectic*nt

When I walked into their apartment, Zoe Jensen and Mariana Plaez were sitting by their kitchen table. Overflowing with magazine cutouts—text, images—the table was barely able to contain the scraps. I felt that if I sneezed too hard I might send the whole arrangement flying. There were only five days until their deadline, and they had lots of cutting, folding, gluing, and re-gluing ahead of them.

Zoe Jensen and Mariana Palaez are two of the three editors of the recently-born Connectic*nt Magazine. Spell- check can forget the red underline. Meant as “a love letter to the state of Connecticut,” the zine was born as a reaction against the dismissive attitude towards the state that Jensen and Palaez found obnoxiously common. “I know so many people that are just like Connecticut’s so lame, there’s no one cool in Connecticut, and a lot of these kids will move to New York or something like that because they have the means to do that,” Palaez said. Palaez herself was eager to escape the state when she graduated from high school. But she couldn’t afford Boston University, so she went to the University of Connecticut instead. “And then I found cool people there!” Palaez said. “I’m like damn, there’s cool people everywhere! But Connecticut just doesn’t get the love.” Jensen herself left Connecticut after high school to attend film school in Los Angeles, but came back a year and a half later. “I just missed this place too much,” she said.

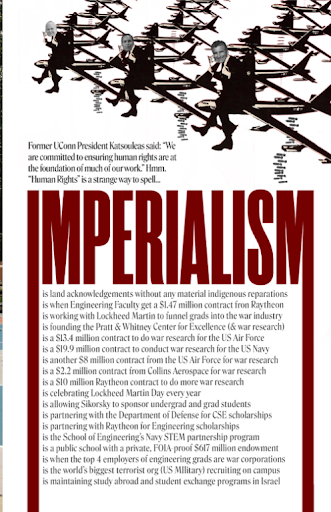

In the zine, many of the submissions are collages. It summons an elementary school era of simple joy, a time before pinging notifications and round- the- clock stress, when it was perfectly natural to spend an afternoon cutting shapes out of magazines, gluing them together, and repeating. But the child-like play that goes into the zine doesn’t keep it from addressing issues worthy of attention. The magazine’s October issue featured a full-page graphic lampooning the University of Connecticut’s proclaimed commitment to human rights. “Human rights is an interesting way to spell Imperialism,” muses the graphic. The page mentions the University’s partnerships with military contractors Lockheed Martin and Sikorsky and the school’s partnership with “the world’s biggest terrorist org (US military).” Delivered without the self-seriousness of other publications, the charge hits hard.

I asked if there had been any particular intention behind the vulgarity in the magazine’s name. “I chose it because I thought it was funny,” Jensen said, laughing. “I really just thought it would be a silly little thing for a few friends.” Now, with roughly 1,500 copies sold and consistent interest from local advertisers, Jensen and Palaez must come to terms with just how popular their zine has become.

Talking with Jensen and Palaez, I considered the similarity between their zine and the underground press of the sixties. The editors bragged about how few conventions of newspaper creation they adhere to. “Fuck a style guide,” Palaez said, laughing. As editors, their main job is simply to select which submissions to include in a given issue. They’re not interested in fact-checking, or telling a contributor how to better word a sentence. Really, they just want to create a low-stress medium for people to express whatever it is they do, or don’t, feel like saying. But, like the papers of the nineteen- sixties that preceded it, Connectic*nt has been very popular. I wondered if the zine’s promise of profitability might pique the interests of any aspiring business-owners. Jensen herself mentioned that she would love to work on Connectic*nt full-time, if possible.

In my conversation with Paul Bass, the editor was insistent that no tension exists between a magazine’s profitability and its ability to generate thought-provoking content. Readers seek content that is stimulating and fresh, and advertisers shell out the most for publications that readers love. Typically, decay at a newspaper results not from profitability itself but from the paper-pushers, HR consultants, and money-grubbers that get hired later.

In the rise and fall of publications, there is something of a life-cycle. Stories about the predatory behavior of a company like Alden are undeniably troubling. Journalists at publications like the Tribune and the Advocate had life-long careers overturned by a handful of nihilistic venture capitalists. At the same time, the tedium of corporate media is precisely what has pushed writers and readers to seek out new platforms and styles of communication, both in the nineteen-seventies as well as today. While Alden chews on the charred remains of the publications it buys, the boring papers it will publish will give even greater incentive for writers to break new boundariess and attract readers in yet more powerful ways.

Yonatan Greenberg is a junior in Saybrook College.