Author’s preface: This article is the product of a four-month-long investigation into how delays in New Haven’s lead poisoning prevention practices affected families with young children in the city, including many refugees. I reviewed over two hundred pages of previously unreleased government documents related to four New Haven addresses, the bulk of which were obtained through three Connecticut Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests. This article involved dozens of interviews with former and resettled refugees, government officials, medical and legal academics, employees of IRIS and other nonprofits, and property owners. Some names have been changed, and some details omitted, to protect the locations and identities of interview subjects.

Before writing this article, I formerly worked at Integrated Refugee and Immigrant Services (IRIS), one of the organizations in this story, as a remote intern in 2020-2021. My work consisted of filing Section 8 applications and UI claims during the COVID-19 pandemic. I met the Naqibzois separately, through sources at Elena’s Light, who connected us through a mutual friend.

This article could not have beeen completed without Elena’s Light, a refugee-led organization dedicated to women’s and children’s welfare in New Haven, that provided Pashto and Dari interpreters under contract with The New Journal.

1

Left in the Dark

Earlier this year, on a cold February day around 2:30 p.m., Shahid Naqibzoi got off the bus from Wilbur Cross High School and walked toward his home in The Hill neighborhood of New Haven, still thinking about favorite class, biology. A tall, wiry fifteen-year-old, Shahid knew he wanted to become a doctor, or maybe an engineer, with the encouragement of his new teachers. When he turned the corner to his backyard and saw strange men digging outside his family’s yellow duplex, he assumed they were “from the government.” In Afghanistan, when U.S.-funded infrastructure began to crumble during his adolescence, he had seen officials in similar attire fix the potholes.

There were four of them, bearded men, with black jackets—military jackets, Shahid thought. He watched as they shoveled gravel out of the back of a white, unmarked van and tossed it into the earth, near the duplex’s drainage pipe. An assortment of children’s toys from the families at the duplex—remnants of a Cozy Coupe and a pink bicycle, half-buried—dotted the back lot, which was surrounded by fence. Shahid tried not to make eye contact with the men who watched him, silently, as he climbed the wooden stairs that hugged the back of the duplex. He walked into his family’s third-floor apartment, where he lived with his parents and five younger siblings.

By noon the next day, when Amila, Shahid’s mom, left the house for a doctor’s appointment, the men were gone. At the south end of the lot, they had left a shadowy rectangle of gray gravel, in a darker shade than the rest of the yard, as if a cloud had floated over and stopped at the edge of the fence.

When Amila and her husband, Navid, first saw the vinyl-sided façade of 18 Dewitt Street, they thought the property was a step up from their first American home. The Dewitt Street apartment was more affordable––a lean $1,200 per month––and closer to the K-8 school in The Hill that four of their six children attended. But after signing their lease, a series of unpleasant discoveries made the property less attractive: mice, insects, and raccoons frequently scurried across the living room floor and into the kids’ bedrooms. Outside the room that Shahid shared with his brother, a long rod of twisted iron swung slightly from the top frame of a bay window.

Later in March, after living there for over a year, the Naqibzois learned another fact about 18 Dewitt Street that had gone undisclosed: the property was contemaminated with toxic levels of lead. A city inspection, conducted after a suspected poisoning at the property, found the chemical on their windowsills, in the dust lying on the stairwell, and, in its most concentrated form, in the soil surrounding the drainage pipe of their house. According to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), soil with lead concentration at 400 parts per million or greater is considered so great a public health hazard that the lead must be removed immediately, and children must vacate the residence. The soil surrounding the Naqibzois’ home, where children used to play, was over three times that number.

What Shahid had witnessed that day in February was the final step of the removal process, called a lead abatement: the legally required remediation of lead-based hazards in a child’s home. When toxic lead is present in the ground, the EPA says, the contaminated soil must be carefully dug up and hauled away. Then, a property owner, usually dependent on hired maintenance contractors, brings a “clean” soil deposit to the premises, making them safe for small children to inhabit.

Six months earlier, their landlord, Shmuel Aizenberg of Ocean Management, was ordered by the city’s Health Department to perform a lead abatement of 18 Dewitt. Yet city officials were aware of the soil contamination as early as November 2020, when an inspector received lab results that confirmed hazardous lead quantities in the property—and in 2016, a city inspection report had found similar levels of contamination. Eight years before the Naqibzois were made aware of it, the property’s history of lead poisoning was marked in the public record.

For the Naqibzois, information about the lead contamination came too late. 18 Dewitt Street wasn’t their first time as Ocean Management tenants—it wasn’t even the first Ocean property where they had lived with lead contamination. The first house in America where the Naqibzois lived, on Howard Avenue, was another one of the hundreds of Ocean-owned low-income properties in New Haven, operated under the names of smaller companies. While living there, at age 2, Shahid’s younger sister tested positive for lead poisoning.

The Naqibzois were not alone. Over the course of this four-month investigation, I confirmed that at least seven refugee families in New Haven, including over a dozen children, were exposed to toxic levels of lead in their homes without their knowledge. Emails, lab results, and city inspection reports from three FOIA requests show that city officials and landlords neglected to remove toxic lead for months from properties in New Haven where refugee families with young children were living.

Refugee families in the United States, who are disproportionately affected by lead poisoning, have little say over the first places where they are told to live, and receive few federal protections against lead exposure during resettlement. Where toxic lead is found, children who left homes once for safety must leave new homes again: after resettlement, a second exile.

2

The Poison

Lead, the most common industrial contaminant in America, can cause significant negative health effects for anyone exposed, but particularly for children under six. At that age, even low levels of exposure can permanently damage brain development. At extremely high levels, lead poisoning can lead to seizures, coma, and death. “No amount of lead exposure is safe,” Erin Nozetz, a Yale pediatrician and the director of New Haven’s Lead Task Force, told me.

Yet the behavior of New Haven landlords form a pattern: they often fail to remove lead contamination, or alert families about its presence in their homes, within the time frame required by law. Along with city officials, landlords often fail to provide translated information about the risks to families who don’t speak English, many of whom are refugees. (One reason frequently cited in city documents for inspection delays: “language barriers.”) None of the families that I contacted, with the help of Pashto and Dari interpreters, had been promptly informed by their landlord of toxic lead levels in their home. In some cases, we were the first to inform families of lead contamination in their current or former homes.

Emails, lab results, and city inspection reports from three Connecticut Freedom of Information Act requests show that city officials and landlords neglected to remove toxic lead for months from properties in New Haven where refugee families with young children were living.

The New Haven Health Department’s policy is to inspect a house for lead after a child under six has already been poisoned. So far this year, inspections have discovered lead contamination in at least 44 properties with young children, according to public records. The most common culprit is paint: until 1978, when the product was banned for residential use, lead paint was a staple of American real estate. According to a report by former health director Paul Kowalski, 83 percent of New Haven’s housing stock was built before 1978. The paint is particularly hazardous when it chips or peels, making it easier for a child to ingest.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) considers children under six “lead poisoned” when their blood lead levels (BLLs) are 5 micrograms per deciliter or above. A recent, internally-circulated report from the Connecticut Department of Public Health shows a staggering statistic: while 1.7 percent of Connecticut children under six have BLLs at that level or higher, 43.7 percent of refugee children under six do—nearly one in two children poisoned.

“Refugees and other newcomer persons resettled to the U.S.,” the CDC says, are a “population at higher risk” of lead exposure. One explanation for that higher risk is children’s prior exposure before coming to the United States. In Afghanistan, for instance, a greater presence of lead-based gasoline could signify a greater risk to children. Another, in the CDC’s phrasing, is exposure to risky “cultural practices, traditional medicines, and consumer products”—or as Camille Brown, the director of Yale’s Pediatric Refugee Clinic, puts it, “behaviors of different cultures.”

It’s true that many products made abroad, such as metal jewelry, spices, or cosmetics, contain lead, often because lead is cheap and easy to mold. Yet at best, these assumptions of exposure abroad provide a partial picture: prolonged American exposures to lead are a regular occurrence for refugee children too. During the COVID-19 pandemic, at the lead treatment center where Nozetz works, families took her on a “Zoom walk” through their house, and she’d point out potential hazards. Common sources included peeling paint, windowsills, and stairwells covered in lead dust. If refugee children are placed in further harm’s way, Brown said, U.S. resettlement risks “exacerbating” prior exposure. Children’s BLLs should start to decrease after a few months in lead-free environments; high BLLs after three months could signify that they are still being exposed. One 2017 study suggested that newcomers’ “joint exposure”—first, to lead-based products in a country of origin, and second, to an older home in the United States—was a significant driver of higher BLLs. In the Connecticut Department of Public Health report, “paint/lead dust” is listed as refugees’ primary source of exposure to lead. Contaminated soil is second.

One of the most recent fatalities of lead poisoning in the United States, in 2002, was a refugee child. Sunday Abek, a 2-year-old girl, died of lead poisoning in Manchester, New Hampshire, after the landlord of the property failed to disclose the presence of lead paint in their apartments. Sunday’s mother settled a lawsuit for $700,000 against the property manager and building owner; the property manager was also sentenced to fifteen months in federal prison. Her lawyer said, “had she known the price for coming to America would be the life of her youngest child…she never would have come.”

3

The First Exile

Amila, a skilled tailor and dressmaker, met her husband Navid Naqibzoi in 2003, in their hometown of Khost near the Pakistani border. He was her next-door neighbor, and they married the following year. In 2012, Navid began to work as a medic on a U.S. military base, Forward Operating Base Chapman, in Logar Province. Everything from simple sutures to I.V. drips to EMT calls fell under his purview. Navid accompanied American soldiers on missions outside Chapman, and he was adept at making friends. He liked to crack the occasional grim joke about the American War on the base, which endeared him to the others. At home, he kept details about Chapman to himself.

Eventually, concerns that the Taliban would target Afghans working at the base in Khost became so extreme that Navid warned his family not to venture beyond their walled home except for emergencies. Each morning, he carefully mapped the directions of his driving route to Chapman, so that he could follow another route back home and avoid a tail.

On the advice of a close friend, Amila and Navid applied for Special Immigrant Visa (SIV) status in 2016. For Iraqi and Afghan nationals who face persecution as a result of working for the U.S. military and its affiliates, SIV status is a means of protection by relocating: applicants who are approved for SIV status receive permanent residency and a green card to move to the mainland United States. Successful receipt of SIV status, however, is a notoriously slow, bureaucratic process. In 2018, a group of Afghan and Iraqi nationals sued the U.S. federal government over application delays that lasted as long as five years, which a federal judge later ordered the Trump administration to remedy.

After three years of waiting, the Naqibzois’ SIV application was finally approved. On November 18, 2019, they boarded a plane, for thirty-six hours of flying and an eight-hour layover in Dubai. Shahid was bored: the novelty of his first flight wore off quickly, and he wanted to get on the ground. In Khost, when he watched the World Wrestling Entertainment channel, he especially liked American wrestling aficionado Roman Reigns, whom other WWE audiences loved to hate. “Even though he’s the World Heavyweight Champion!” Shahid protested. He was anxious to see the country Reigns was from, where “they said they don’t have war.”

Upon their arrival in the United States, a refugee resettlement caseworker told the family to move to a multi-family unit on Howard Avenue, at that point owned by an affiliate of Ocean Management. Navid searched for a medical job in New Haven, but no hospital in Connecticut would recognize his certificate from Chapman. He worked as a delivery driver downtown, for Uber and DoorDash, to make money. He learned the addresses of Yale’s residential colleges, and grew to appreciate Silliman College residents for their reliable late-night Papa John’s orders.

Shahid and his siblings, including his younger sister, who goes by ‘Naz,’ underwent a mandated “refugee health assessment,” which included testing for the children’s blood-lead levels, measured in micrograms per deciliter. When Naz’s results came back from Yale-New Haven Hospital, a few days later: her BLL was nine micrograms per deciliter, placing her above the ninety-ninth percentile of children in America with respect to BLLs.

“We were so worried,” Shahid said. There are few cures for lead poisoning, besides changing a child’s environment. Unsure of what to do, Navid and Amila wiped down every surface of their home, and proceeded to bathe their daughter, twice a day, for several days following her diagnosis.

The timing of Naz’s lead test, soon after arrival, could suggest prior exposure or exposure in America. (A later inspection of their apartment at Howard Avenue found lead paint on twenty-seven surfaces.) But without prompt action, a secondary, prolonged exposure would further imperil her health. “The longer you’re exposed to lead, the higher the likelihood there will be long-term cognitive effects on children,” Nozetz said. After weeks and months of chronic lead exposure, neurotoxins can lurk in a child’s system for decades, leaving residues behind in bones and teeth.

A few months after their arrival, Navid’s cousin offered the couple his old apartment in The Hill, 18 Dewitt Street, down the street from the K-8 school where Navid’s younger children would go. The apartment was along bus routes that could eventually take Shahid to a magnet high school. Amila and Navid accepted.

In early 2020, three months after her initial assessment, Naz tested positive for lead poisoning again. According to New Haven city law, any report of a child with blood lead levels over five micrograms per deciliter triggers a city inspection, which must take place within five days of the child’s lead report. The first inspection came eleven months later.

4

The City

Cases like Naz’s weren’t supposed to keep happening. In May 2019, a class of over three hundred families, represented by the New Haven Legal Assistance Association, sued the City of New Haven for neglecting lead-prevention protocols. Muhawenimana Sara, who was poisoned in 2018 at age 3, was one of them. Displaced from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Sara’s family moved into a three-bedroom apartment in the neighborhood of Fair Haven. Her lead tests upon U.S. arrival presented no concern; but one year later, Sara’s BLLs had risen to 10 micrograms per deciliter.

Amy Marx, a New Haven Legal Assistance (NHLAA) staff attorney, attributed Sara’s poisoning to U.S. exposure. The lead paint on Sara’s front porch was chipped and peeling, increasing the risk of ingestion. The city had made one attempt to send an inspector unannounced to Sara’s home, who gave up when nobody was home and “left a business card with a note and materials in English only.” Court documents allege that the inspector “was aware that the family spoke Swahili.” The year before, the city had relaxed the threshold for lead inspections to a child’s BLL test of twenty micrograms per deciliter—four times the CDC standard. City administrators blamed staffing issues.

The City signed a settlement agreement with the suing class in May 2021, creating a thirty-one-step oversight process of legal and regulatory duties to ensure that the city would follow pre-existing Connecticut law. After a poisoning report, inspectors must come to a child’s home within five days, armed with dust wipes and containers for water and soil samples, to send their findings to a laboratory. If lab results yield evidence of “dangerously hazardous” levels of lead, the city must notify every family living in the house, as well as the landlord, within another five days. After that, responsibilities lie with the landlords: they have forty-five days to begin an abatement. “The biggest change here is a determination to make sure that what is in the law actually happens,” Marx said in a press conference following the settlement.

But delays and the lack of language access persisted in Naz’s case. When the city received notice of Naz’s first positive test, in 2019, and again in 2020, inspectors attempted unsuccessfully to reach the Naqibzois to schedule a follow-up lead inspection. In February of 2020, a city inspector sent a letter to the family’s Howard Avenue address, asking why they had not responded to her queries. The letter was sent in English only, with Naz’s first name (her legal name) misspelled.

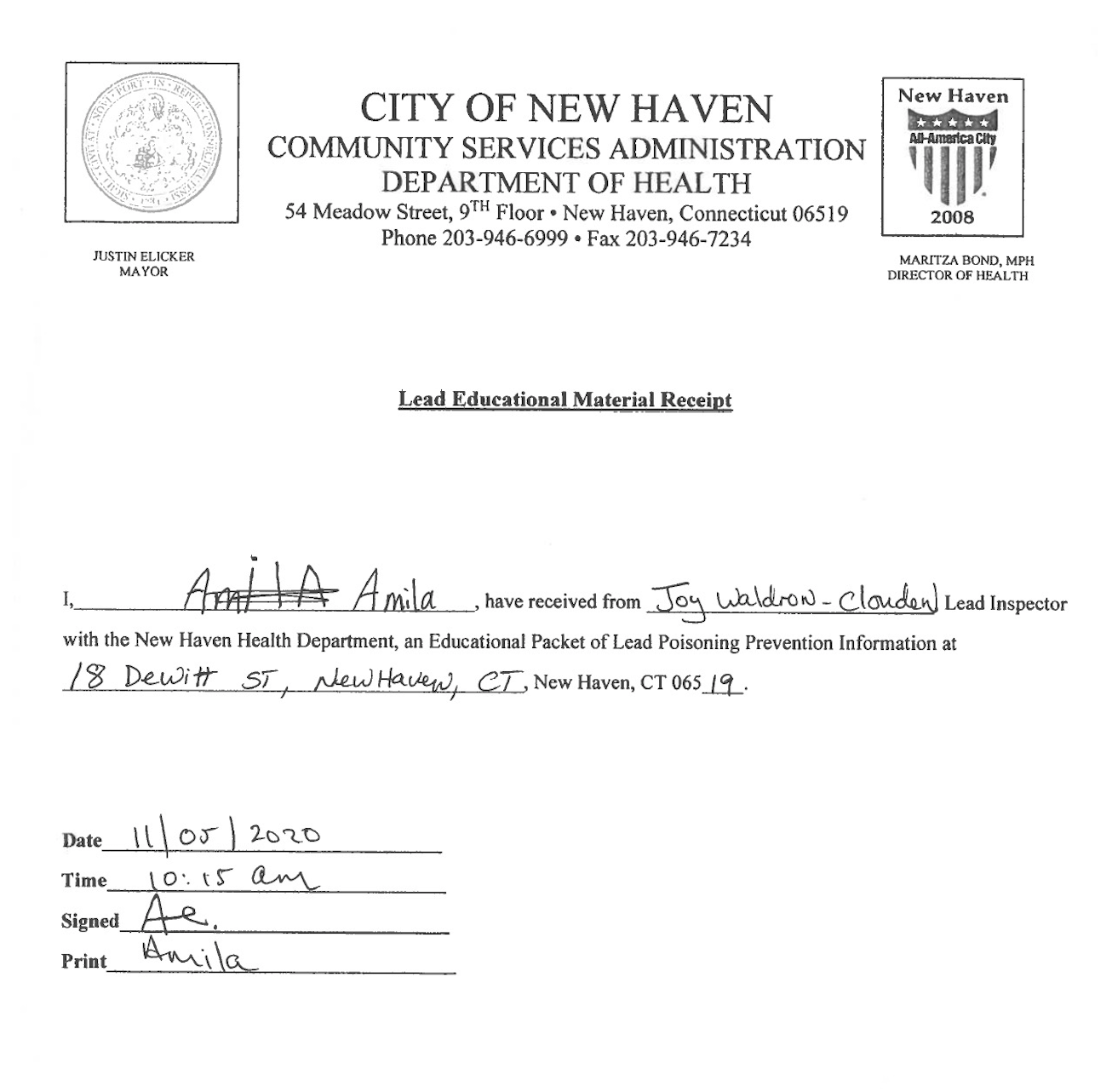

The family left Howard Avenue later that year, in September. Another city inspector, Joy Waldron-Clouden, located the Naqibzois at 18 Dewitt Street on November 5, 2020. According to a summary of her visit, Waldron-Clouden’s first training as a city inspector was less than three weeks beforehand. At the time, none of the families in the duplex spoke English.

While 1.7 percent of Connecticut children under six have high blood-lead levels (BLLs), 43.7 percent of refugees under six do—nearly one in two children.

On November 24, the Connecticut Department of Health emailed lab results from the visit to Waldron-Clouden and the director of the Health Department, Maritza Bond. Residual lead was present at “dangerously hazardous” levels, high enough to trigger abatement, in two locations: in the stairwell, and the soil in the backyard. On the left side of the backyard, lead was found at concentrations of 1560 parts per million, well above the threshold of four hundred parts per million. At that level, the E.P.A. says, backyard soil isn’t fit for a home garden, let alone for a child under six to play in. (On the city’s copy of the lab results received on November 24, that lead amount is highlighted in bright yellow.)

After receiving the lab results, Waldron-Clouden didn’t file an inspection report until January 8, 2021, more than two months after her initial visit. That same day, she sent an order to Wade Beecher, a maintenance employee of Ocean Management, to wipe down dust in the stairwell, but did not mention soil contamination. At the end of the inspection summary form, she filled out the paperwork to conclude the case:

Per section 19a-111-14(a) and 19a-111-2(e) of the Lead Poisoning Prevention and Control Regulations, a lead abatement is required for this property: { } YES { } NO

Waldron-Clouden marked a check by “NO,” and wrote her signature. The report was filed eighteen months after the city received Naz’s first positive test for lead poisoning.

After Beecher, the maintenance manager, claimed to have removed the lead dust in the stairwell, Waldron-Clouden re-inspected the house in June. “I have determined that the order letter to abate lead from this premise, data January 8, 2021, has been met with compliance,” she wrote. Temporarily, the case was closed. By the time health officials finally sent an order to Beecher to remove lead-contaminated soil in the Naqibzois’ backyard, on August 3, 2021, the city had known about the toxins present for over nine months.

In the same visit, Waldron-Clouden was required to attain a family signature, assuring the city that the Naqibzois had received an Educational Packet of Lead Poisoning Prevention. Amila signed her name in big, all-caps letters. Waldron-Clouden crossed out Amila’s signature and rewrote Amila’s name in her own lower-case handwriting.

I met the Naqibzois at 18 Dewitt Street for the first time in March, after Shahid had returned from school one day. Navid opened the door and invited me into the living room, where we sat on burgundy IKEA carpets under a framed plaque of the Shahada. Over tea, we spoke about the lead found in their home. I provided them with a copy of the city’s inspections, although Amila and Navid told me that the family was already looking for a new house to live in. “These little animals,” Navid said, pointing to the mice-infested walls and shaking his head. “We can’t sleep at night!”

By the time health officials finally sent an order to Beecher to remove lead-contaminated soil in the Naqibzois’ backyard, on August 3, 2021, the city had known about the toxins present for over nine months.

Naz, who is now four, walked into the living room, wearing a dark-green dress with golden trimming. She was playing with a green balloon, and had shoulder-length curls. According to her parents, their daughter struggled with learning words well after turning three, and she speaks far less than other children her age. Sometimes, inexplicable outbursts led to fights with her father—even more so, her parents worried, than a typical four-year-old. Troubled, Amila and Navid returned to Yale New Haven Hospital for more follow-up appointments. “A year ago, we didn’t understand what she’s saying,” Navid said. “Now, she is O.K.” Some doctors attributed Naz’s delayed speech to hearing problems or “oral-motor problems.” Her full range of symptoms, however, also closely resemble those of long-term lead poisoning victims.

I showed Amila the document where the inspector claimed to have acquired the family’s signature, eighteen months prior. She stared at me, uneasy. “That’s my handwriting,” she said, looking at the crossed-out name, “but I don’t know what that says.” Amila and Navid say that the inspector did not come with an interpreter. City documents show no record that one was present.

5

Housing the Evacuees

Compared to other housing assistance programs that receive federal funding, housing for resettled refugees is far less regulated—largely because their federal grants are not directly related to housing. The “Lead-Safe Housing Rule,” which applies to Section 8 housing and other programs funded by the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), requires, among other things, that landlords offer tenants a ten-day window to conduct lead inspections in their prospective homes before signing a lease. Property owners must also disclose every “record and report” of lead contamination in federal public housing, according to the Housing Rule.

But refugee resettlement is not within HUD’s purview, even if housing is involved. Nonprofit “resettlement agencies,” under contract with the State Department, handle the U.S. refugee admissions program, which includes arranging housing for families when they arrive. Since these agencies’ funding is determined by the number of refugees they resettle, the Trump administration’s cuts to refugee admissions wrought long-lasting damage to their staffing and infrastructure. By August last year, when the Taliban took over Afghanistan, and thousands of SIV applicants and “humanitarian parolees” sought refuge in the United States, the nine “voluntary agencies” that assist refugee resettlement had not fully recovered.

For New Haven’s resettlement agency, Integrated Refugee and Immigrant Services (IRIS), the greatest hurdle was finding affordable housing for refugees once they arrived, as rent is usually their greatest expense. Chris George, the executive director of IRIS, described the process as “a nightmare.” When George arrived as director, only one or two landlords in New Haven were willing to rent to refugee clients, most of whom possessed no credit history. In 2006, IRIS had taken the unprecedented step of co-signing refugee clients’ leases. “Most resettlement agencies would call us crazy,” George told me. Other agencies won’t risk the liability for paying their clients’ rent, but IRIS wanted to guarantee their housing security. George also said that, after Sara’s poisoning in 2018, the nonprofit decided to conduct lead inspections into any home where refugee clients with young children would be living, before those families arrived.

In practice, however, the pre-arrival inspection policy seems rarely implemented. I confirmed at least four cases of families who were placed in homes by refugee caseworkers, only to discover lead contamination afterward. One SIV holder living in The Hill, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, told me that IRIS claimed to inspect his apartment before sending him there with his wife and three children in 2019. “[IRIS] said it was fine,” he insisted. The property in question was in poor condition: in the first week, he noticed illegal utility tapping and incorrect metering in the basement. The house also had a long history of lead contamination, according to public records—three children were poisoned while living there, in 1999, 2002, and 2017. His youngest daughter became the fourth child poisoned while living on the premises in 2020, after which an abatement was completed.

“I think nobody would care for such a family, an immigrant family,” he told me. He wanted to move, or file a complaint—but after searching for weeks, he couldn’t find another affordable place to live, or an attorney to represent him. Since he had lived in the States for over a year, and was working, he was no longer eligible for many refugee and rental assistance programs; the U.S. resettlement system considered him “self-sufficient.” “Everything is going well, except for housing, and the landlord. They make it dangerous for my children.” He had a guess as to why his family was mistreated by his landlord, an affiliate of Ocean Management: “[The landlord] knows we are immigrants, so they think we won’t complain.” This year, he began receiving legal aid services.

In another case, a former soldier in the Afghan army, whom I’ll refer to as Amir to protect his identity, arrived in the United States in November 2021, living in his uncle’s house until IRIS found a home that would be suitable for him, his wife, and his daughter, who was eight months old. His caseworker eventually found him a unit in a brick building with dusty windows and stained curtains, a stone’s throw away from the Yale Bowl.

After their move to the new home in December, Amir’s daughter tested positive for high blood-lead levels. Just as in Naz’s case, the test triggered a legal duty for the city to inspect the property within five working days of the report. Internal city documents show that the Health Department did not inspect Amir’s apartment until February 9, 2022—almost two months after Amir’s daughter had tested positive. The reason for the delayed inspection, written on Health Department documents in neat cursive, was, once again, “language barriers.”

When Health Department inspectors arrived at the apartment, they found toxic amounts of lead paint at seventeen different locations, including within the family’s kitchen, living room, and bedroom. The report ordered the landlord to repaint the interior rooms and the building’s front porch, where lead on the doors and windows were sixteen times greater than the concentration deemed “hazardous.” In response, the landlord presented Amir with a document and asked him to sign it. “During time of construction, [Amir and his family are] going for a few days (3 days or more) to their relatives with his family,” the written agreement read. “During this time the managers will change the windows, paint the apartment.” Amir agreed, and left for a few days in March.

Amir’s landlord made no mention of lead or hazardous health conditions in the agreement. What’s more, the 2021 settlement requires that where lead paint is found in New Haven, children and their families must be relocated “at the expense of the property owner,” and not on their own dime, as Amir did. Amir told me that he guessed why his landlords removed the paint, after hearing from his daughter’s pediatrician and reading educational materials sent by the Health Department. Had he depended solely on his landlord for information, he wouldn’t have known that lead paint was even present.

Amir and his family weren’t the only IRIS clients placed in a lead-contaminated property via a pre-arranged lease: his caseworker, Zaker Sultani, was resettled to one himself. In an earlier interview with me, Sultani confirmed that before he worked for IRIS, he had formerly lived at 18 Dewitt Street—the Naqibzois’ past property. Our conversation in February, 2022 was the first time he had heard about the toxic lead in his old backyard. His children, a fifteen-month-old and a four-year-old, regularly played in the soil behind the house, sometimes for two hours a day. “Ocean Management was very callous, very reckless,” Sultani told me. “From day one, the property was filled with mice.”

I could not confirm whether Amir’s or Sultani’s homes were tested for lead before they arrived, either by their landlord or IRIS. But the eventual discovery of lead contamination on those properties suggests that pre-arrival inspections did not occur.

Resettlement agencies like IRIS are required, as a condition of their federal funding, to ensure that refugees’ housing is “free of visible health and safety hazards and in good repair.” Their cooperative agreement with the State Department states, “no peeling or flaking interior paint” for dwellings built before 1978. “IRIS is stuck between a rock and a hard place,” Amy Marx, the NHLAA attorney, said. The organization is responsible for finding refugees housing, but it remains under-resourced, and constrained by poor conditions that afflict most affordable units in New Haven.

But had he depended solely on his landlord for information, he wouldn’t have known that lead paint was even present.

When I arrived outside Amir’s building for the second time, hoping to speak with his property owner, a man of middle age in a gray pickup truck arrived. He got out of his car and stared at me icily. I explained to him that I found the address and its lead paint inspection results from New Haven’s public records.

“Why do you all care about this?” he said. “They”—gesturing at the building, where Amir’s family lived—“had lead in them before they arrived. They came here from Mandy.” Mandy Management is another local landlord whose properties are frequently found with housing code violations. When I asked whether any tenants on the property had been informed of their rights while the landlord removed lead paint, as required by law, he said he did not care to answer.

“I shouldn’t be talking to you,” he said. “I’ll report you for trespassing!” He told me to leave.

One IRIS employee recounted the condition of a basement in one Mandy Management-owned apartment, which was being rented by refugee clients. It “would make you vomit,” he told me. There was “raw sewage, spilling onto a basement floor, attracting maggots, it was the result of ridiculously dumb plumbing.” Despite the risks of renting with Mandy or Ocean, the employee said, there are few alternatives for refugee clients, given the two firms’ dominating shares of affordable housing stock in New Haven. Multiple IRIS employees wished not to speak on the record for fear that Mandy and Ocean Management would retaliate by refusing to rent to future clients.

Mandy, alongside Ocean Management, have been called “investor-landlords” in local press. “The pattern we see,” Marx said, “is that these landlords continue to neglect their properties.” ‘Investor-landlords’ partner with private-equity firms, who package landlords’ loans into mortgage-backed securities, then purchase formerly-owned properties with the extra credit and convert them to rental housing, largely in low-income neighborhoods. Ocean’s director, Shmuel Aizenberg, put 101 multi-family homes on the city’s housing market as a $52 million package deal last month. This Monday, Aizenberg pleaded guilty to charges brought last October for fifteen housing code violations at three properties. He paid a fine of $3,750.

A representative of Ocean Management told me in February that the company did not currently keep a maintenance agency. “We get Farnam Realty Group to outsource for us,” the representative told me. (As of April 30th, Farnam, a local brokerage firm, had severed ties with Ocean Management.)

When I inquired about Wade Beecher, the maintenance manager of 18 Dewitt Street, the representative informed me that as of January, Beecher was no longer an employee at Ocean Management. In May, the representative said they could not comment on individual properties or ongoing legal cases.

6

The Second Exile

By April of this year, the Naqibzois had moved to their third home since arriving in the United States, a recently-constructed, affordable-housing complex, still close to their children’s K-8 school. Amila and Navid successfully applied for a unit there. It is clean and safe and the rent was slightly cheaper.

Erin Nozetz, the Lead Task Force director, recalled asking a social worker with a poisoned client at the hospital about what could fix the lead contamination crisis: “She said, ‘if I could wave a wand, affordable housing.’” Median rent in New Haven has risen sharply, and getting off the waitlist for a Section 8 housing voucher, alongside about eighteen thousand others in line, can take seven to ten years. “Where do you go?” Nozetz asked.

I spoke with Alice Rosenthal, the director of Yale-New Haven Hospital’s medical-legal partnership, about the impact of the city’s lackluster prevention policies on vulnerable families. After I described the case of the Naqibzois to her, she was silent for a moment. “That’s terrible,” she said. “You’re leaving a kid in a home that’s incredibly vulnerable to further permanent damage for their brain. That’s egregious.” Yet accountability for affected families may prove elusive. Rosenthal explained that families who learn about lead contamination later, from a past apartment, have little to no hope for a successful lawsuit, especially if they cannot prove where their child was first poisoned.

Advocates hope that H.B. 5045, which passed the Connecticut House on May 3rd with the support of the governor, will tighten the state’s threshold of “actionable” lead levels in children to match the CDC’s newest standard, at 3.5 micrograms per deciliter. As the House debated the bill, New Haven’s leadership on lead since the settlement was cited as a positive. Mayor Justin Elicker has maintained a stricter standard for investigating lead cases since his election in 2020. But Connecticut is just the beginning—and legislation does not always imply enforcement. New Haven is an “improvement upon other cities,” Brown and Nozetz say. But these improvements haven’t met the needs of families like the Naqibzois.

Maritza Bond, the current director of New Haven’s Health Department and the person who received the Naqibzois’ case files by email, has also expressed support for the bill. She announced her candidacy for Connecticut Secretary of State last March. As she considered a run in September, 2021, Bond said, “I’ve led New Haveners through one of the worst moments in human history, while tackling long-standing, unanswered issues like lead poisoning in our infants and children.”

‘These are children—this is children’s development!’ she said. ‘I’m not even understanding why this is a conversation. How many kids do we have to poison before we take this seriously?’

When Bond was hired as Director in January 2020, after leading Bridgeport’s Public Health department for three years, she made lead poisoning a major priority. The reason so many lead abatements appear in public records at all, some have argued, is because of Bond’s updated procedures, digital record-keeping, and newly hired lead inspectors—including Joy Waldron-Clouden. Even Amy Marx, who closely observed the city’s reforms after the class-action lawsuit, was impressed.

In July 2020, Bond blamed the city’s COVID-19 shutdown for delays in identifying young children with lead poisoning. From mid-March to early June, she told the New Haven Register, the Health Department received no new reports of high lead levels because “there was a delay in routine children’s care.” Naz’s case, however, began in November 2019, well before the shutdown. While the city’s first inspection delay in 2020 could conceivably be explained by the pandemic, the Health Department had lab evidence of her home’s contamination for months after in-person inspections and home visits resumed. Marx guesses that the delays were due to the “period of transition” for Mayor Elicker’s administration, which had to close an overload of lead poisoning cases left from the Harp administration. Even so, the Naqibzois’ case is “totally unacceptable,” Marx said. “But not unexpected.”

Rosenthal points to Massachusetts, where tenants must receive a property’s lead contamination history before signing a lease, or the District of Columbia, where inspectors have broader authority to assess any houses where children are living, as more preventive models for lead poisoning. “But that’s really it, across the country,” Rosenthal said. “Generally, we’re being very reactive.” Landlords, insurers, and the lead paint industry have successfully fought lawsuits and lobbied on the state and federal level against greater protections. In Connecticut, health departments have even pushed back against the more stringent standards in H.B. 5045, protesting that it presents an undue burden on inspectors and officials. Rosenthal scoffed at that idea. “These are children—this is children’s development!” she said. “I’m not even understanding why this is a conversation. How many kids do we have to poison before we take this seriously?”

* * *

Recently, I joined the Naqibzois as they broke the day’s fast at sundown. It was Ramadan, and Naz was preparing to start kindergarten the next fall at the school across the street. As we sat on long maroon couches, trading flatbread, dishes of beans with lemon, pakora fritters, and vegetable samosas, Navid described his past annual vacations to Afghanistan. Each time, he tried to bring a gift to the friend who had helped him with his SIV application in 2016. But with the Taliban’s takeover, the vacations are no longer possible, and his friend is still in the country. I asked whether the family had any way of contacting him, and Navid shook his head. “I can’t reach him. I don’t even have his email anymore.” Amila and Navid were optimistic about their children’s new beginnings, but dispatches from Khost were difficult not to think about. As foreign aid evaporated, and their friends reported “no salaries, no food, no money,” Navid tried to budget $550 each week and wire it to his parents in Afghanistan. He did not know whether to expect to see them again.

After dinner, Amila and Navid packed away the leftover flatbread for tomorrow’s 4 a.m. pre-sunrise meal. Shahid and his younger brother deciphered the paperwork required for Naz’s entry into kindergarten while Amila started cutting red linens for her daughter to wear on her first days of school. In the living room, as his sisters turned on a Bollywood movie, I talked to Shahid about his weekly routine. He attended an IRIS youth group after school on Fridays, in the church next to Yale’s Timothy Dwight College. He would start attending again, after Eid.

Shahid remembered Eid last year. It was May 2021, and his friends took him to Lighthouse Point Park for a barbecue. The boys had hoped for an empty park, so that they could dance Attan along the boardwalk. Attan is a traditional Pashto dance, involving left-to-right pivots, careful steps, and twisting wrists. “There were Americans, and they were taking photos of us, they were recording us,” Shahid recalled. He didn’t like it, at all—the silent gaze of strangers made him feel self-conscious. The boys preferred to dance unseen, going out as late as 3 a.m. in the park to do so.

Shahid guessed the Americans “thought we were Arab, or from Turkey.”Eventually, the boys asked the onlookers not to post any of the photos they took, and his friends decided to post their own videos of Attan on TikTok, to claim the recordings for themselves.

In past years, the park had hosted the annual New Haven Lead Poisoning Awareness Picnic, the short-lived brainchild of former health director Paul Kowalski. “We’re trying to keep the issue alive,” Kowalski told the New Haven Register in 2018. At one picnic, Kowalskidismissed the lead-related lawsuits against the city as “lies and distortions.” The fair was discontinued when Kowalski resigned, in 2019, after he was named in Marx’s class action suit. Picnics featured a banner with a slogan used in lead awareness campaigns across the country:

LEAD FREE IS BEST FOR ME!

The message is no longer on display at Lighthouse Point Park. But on the day Shahid visited with his friends in 2021, to remind their onlookers in the park who they were, he hung the tricolor banner of Afghanistan from the ceiling of the park’s wooden pavilion—though today, the Taliban’s flag flies in Kabul. Wind buffeted the flag in the direction of the lighthouse, whipping bands of red, black, and green toward the sea. The boys kept dancing Attan.

—Tyler Jager is a senior in Silliman College.