The blue whale model loomed over me, the white paint of its belly striated by blue light. Sounds of ocean waves crashed and drifted in and out of my ears as I peered into each diorama of the Ocean Hall exhibit, longing to step inside. I closed my eyes—I want to stay here forever, I thought, jetting across the sea with giant squids and ammonites. I was 6 years old, and my fascination propelled me through every collection of the American Natural History Museum. That feeling—the intense desire to walk out of your own body into a world you can only imagine—was magic.

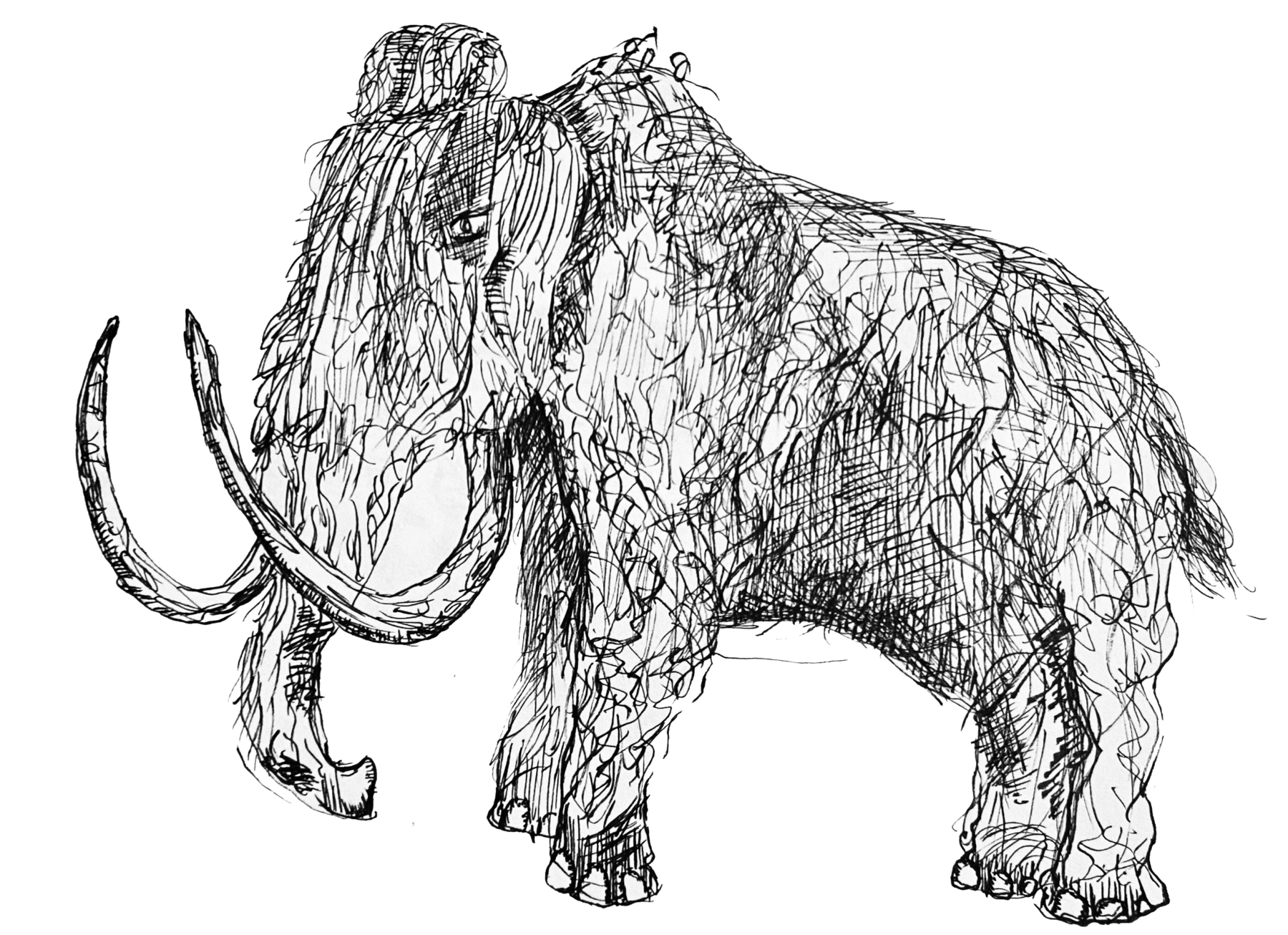

This is my earliest memory. At that age, all aspects of natural history captivated me. Dinosaurs leapt from the pages of books and became characters in a fairytale I could step into. I dove deep into the sea of natural history media: I spent hours watching documentaries where I saw mosasaurs swallow sharks whole. During reading periods at school, I’d flip through stories of archaeologists and paleontologists unearthing ancient civilizations and specimens in National Geographic Kids magazines, and I’d collect figurines of mammoths, saber-toothed tigers, and sauropods. Other kids my age also let their imagination mingle history and nature. Some of my friends pretended they were ancient royalty, while others dug for fossils in the sand next to their castles. We saw transformation in everything: we watched caterpillars turn into butterflies, and we ran around the playground with arms spread like the wings of a monarch. As we got older, we shed more than cocoons. We let the remarkability of the natural world slip.

I can’t remember when I stopped dreaming of dinosaurs. My figurines are still on my bookshelves, but that child who could name creatures long extinct, who took pride in classifying them as herbivores and carnivores, feels like a stranger. Her fantasies of swimming with the squids have abandoned me—or rather, I was the one who abandoned them.

Trace fossils remain, reminding me how she lived her life devoted to nature and driven by curiosity. I still love museums and world histories, but natural specimens just didn’t stick. I don’t know why, but my world became far removed from trilobites and pteranodons. Until recently, that is.

This summer, I interned in communications at the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History. As I peered through each of the Peabody collections—Invertebrate and Vertebrate Paleontology, Anthropology, Paleobotany, Entomology, and the Babylonian Collection—I searched for objects that spoke to me, that I thought would catch the eye of online audiences on Instagram, TikTok, and Twitter . Collection managers would tell me why they mattered in scientific research or in distinct cultural contexts, and I’d pore over books in Sterling Memorial Library to learn more. I’d look at trilobites up close in Invertebrate Paleontology and then scrounge for information about what the life of these distinctly-diverse and highly-populated arthropods were like before extinction. I even got to see the skeleton of Togo, the heroic sled dog of the 1925 serum run to Nome, Alaska, that saved many lives. My job was to translate these complex pieces of information into digestible bits for a broader audience on social media. In videos, and writing, I told the stories of inanimate objects and specimens in pursuit of the answer to the question: “Why do objects matter?” This question was to be seen as the guiding point for each story. It is what drew me to the position—I heard that child’s voice again, telling me that it was time to listen to the millions of voices of the past.

The work was slow. Not every object yields an interesting story. Sometimes, the work meant looking at a pile of rocks that had been stored in cabinets for hundreds of years. I wished these fossilized creatures could whisper in my ear all the secrets from the generations of hands they have passed through – tell me about their birth and creation, under what conditions they lived and died, or how they toiled in the mysteries of the natural world. There is something inexplicable and magical about seeing the vestiges of the past up close. One day, I was looking at a collection of cuneiform tablets in the Babylonian Collection. There was nothing particularly interesting about their contents—just letters detailing finances to family members and other economical logistics—but within the black crevice, incised into the clay, was the name of the scribe who had crafted it. I could almost see the stylus touching the soft clay, and the tablet drying in the sun. I imagined it making its way underground, surviving over hundreds of years, only to reemerge in a small box, neatly tucked away inside a wooden cabinet in the Yale Peabody.

Every moment spent in the collections is an intimate dance with curiosity. Time slows down so much that it begins to move backwards. I surrender to my curiosity, opening drawer after drawer, ignoring the Latin names I can barely pronounce. I hold dinosaur bones and mammoth teeth, peer into the incisions made into the clay of cuneiform tablets, and stare wide-eyed at jars full of maggots. I pull out scientific articles, and revel in others’ research. All this I haven’t had the excitement to do since I was a kid. And I’m able to take fragments of the collection with me in the pieces of information I collected along the way.

Enheduanna, an Akkadian princess and high priestess from the twenty-third century BCE, is known as the first named author in human history. She was a poet who wrote moving stories and incantations to the goddess Inanna. When I think about her writings in tandem with older pieces of the collection, like dinosaur bones and little trilobites, I think about how one can tell the story of time that is forever rolling. In my head, I swim through the Cambrian Explosion to the Ice Age and try to leap into the present, wondering how we got from microscopic creatures in the sea to prayers spelled out on clay tablets. These are the shifts in humanity and in the natural world that can be unveiled after opening one’s mind to the curious life of objects. Throughout all this time they have remained intact. Regardless of their popularity, old bones outlive us all.

— Daniella Sanchez is a sophomore in Morse College.