It’s 8:35 on a weekday morning, and students are filing into the Augusta Lewis Troup school in New Haven. Visible through the glass face of the building, clusters of middle-schoolers chat unhurriedly. Backpacked students bottleneck at the school’s front doors and spill out onto the wide stretch of pavement outside.

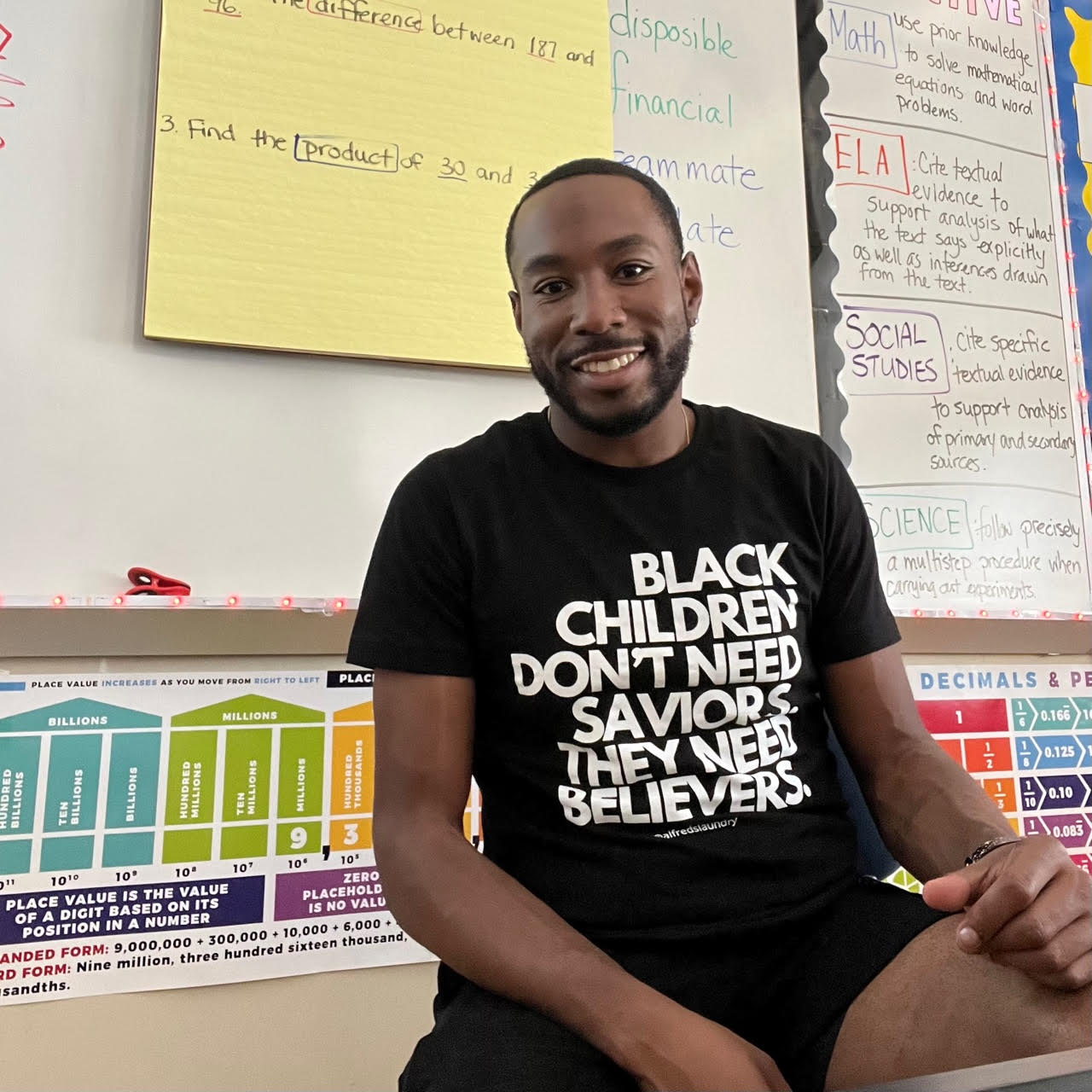

Sixth-grade teacher Da’Jhon Jett has been preparing in his classroom since 7:15 this morning. Today, his three gifted and talented students—students who read well above a sixth-grade level–might finish independent work early. Jett hopes that they’ll use the advanced books, purchased with his own money, to occupy themselves while he teaches four of his other students to identify the letters of the alphabet. Of his twenty-one students, four are learning English as a second language. Four are working on letter identification, and six need more special education support than they currently receive. Jett is not trained as a teacher of special education or English Language Learners (ELLs). But since Augusta Lewis Troup lacks enough specially trained educators, these students have landed in Jett’s classroom.

Low pay and tough working conditions have triggered a mass exodus of teachers from the profession. Nationwide, starting teacher salaries have sunk to the lowest level since the Great Recession (after adjustment for inflation). Pay—decided years in advance by union contracts–has not kept up with the rapid rise in cost of living. Since January 2021, rates of resignation have grown in educational services faster than in any other industry because of low pay and overwhelming expectations. .

In New Haven, the impact on students is especially dire. The city can’t compete with the salaries and working conditions of other Connecticut districts, which benefit from more local property tax revenue. Teachers are leaving New Haven to fill better-funded vacancies in wealthier districts, primarily in Fairfield, leaving the teachers who stay to pick up the slack. All six of the teachers I interviewed for this article know people who recently left the district.

Ryan Boroski is a Social Studies teacher at the Cooperative Arts & Humanities High School. “Two of my friends left this year,” he told me. “One was going to make 50 percent more and one was going to make 35 percent more.”

When some teachers leave, class sizes increase for those who stay. Steve Baumann, an eighth-grade science teacher in his tenth year at the Conte West Hills school in New Haven, explained how classroom management suffers in large classes: “If you have twenty-five students and you have even three that are really off-behavior, it can really throw off the dynamic of the whole class.” Jett also said that he often feels unable to teach effectively with so many students in the classroom. Leslie Blatteau, President of the New Haven Federation of Teachers Local 933, said, “Right now we’re juggling the jobs of many people…it wears on energy and morale.”

All six of the teachers interviewed had classes larger than twenty-five students. Eighteen or fewer is generally considered ideal.

Jett, who is Black, began teaching because he wanted to show students of color that “we can…lead in the classroom.” However, with increasing pressures from the school to cater to students with vastly different needs, Jett told me, he has little time to get to know his students one-on-one.

Before moving to New Haven, Jett taught in Hamden, where average proficiencies in math and reading are 43 and 50 percent, respectively. In New Haven, these rates are 22 percent and 35 percent. Jett attributed the discrepancy in achievement between New Haven and Hamden in large part to overwhelming class sizes. This year, Jett was relieved that his class only had twenty-one students, a decrease from last year’s twenty-seven-student class. But he still struggles to get everyone on the same page. Of the low reading levels among some of his students, Jett told me, “I didn’t know until I got there. I didn’t believe it until I got there. I just didn’t think it could be that low.”

Though conditions of teaching in New Haven—class sizes, low pay, and long hours—have induced some teachers to leave the district, the six New Haven teachers I spoke with are committed to helping their New Haven students. Teachers cited New Haven’s unique diversity and the new union leadership’s commitment to improving teaching and learning conditions as reasons for staying. The New Haven school district is in the top one percent in the state for racial and ethnic diversity, and 88 percent of its students are Black or Latinx.

Blatteau, who has taught social studies in New Haven since 2007, won her election to union president in December 2021. She ran alongside a slate of candidates that included Wilbur Cross High School counselor Mia Comulada as secretary. Before the election, Blatteau and her colleagues asked teachers what they wanted to change about their jobs. Many responded that their “working conditions are students’ learning conditions,” and that students and teachers have “shared concerns, experiences, values, and should have shared action.”

The city can’t compete with the salaries and working conditions of other Connecticut districts, which benefit from more local property tax revenue. Teachers are leaving New Haven to fill better-funded vacancies in wealthier districts, primarily in Fairfield, leaving the teachers who stay to pick up the slack.

The concerns that Blatteau and her colleagues saw emerge in conversations with teachers—especially the stagnant pay, despite growing responsibilities–were similar to those I heard. All of the teachers I interviewed said they worked more than the 6.75-hour day stipulated in their contract. Kris Wetmore, a visual arts teacher at New Haven’s Cooperative Arts & Humanities High School, told me she’s improving her work-life balance and trying not to work beyond 7:30 a.m. to 2:15 p.m., “the hours I’m getting paid for.” Still, Wetmore admitted that she usually has to get to work early and spend some time working on weekends to prepare for the week’s lessons. Jett added, “If any of us just worked for the 6.75-hour day, no one would get anything done.” No one felt that their pay fairly compensated these long hours.

Boroski feels low teacher pay reveals the city’s priorities. “I know no one gets into this job for the money, but…the salary in New Haven is a reflection of the lack of respect for teachers.”

Teachers have long been subject to lower salaries than similarly educated professionals for their demanding work. At the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, Blatteau explained, wages stagnated when the city negotiated a pay freeze that stopped the regular schedule of raises stipulated in the union contract. Since teacher pay schedules lay out pay for a teacher’s entire career, a one-year pay freeze meant that teachers were set back a full year in their schedule of raises. “This really robs teachers who are going into retirement because their pensions are dependent on their salary,” Baumann said, emphasizing the impact of pay freezes on long-term teachers.

Local activists and union organizers have attributed the deficit in New Haven public school funding to Yale’s paltry contributions to the city. Davarian Baldwin is a political science professor at Trinity College and Director of the Smart Cities Lab, which facilitates collaboration with eleven cities on problems involving municipal services including public transportation, housing, and schools. In the past, Baldwin has worked with New Haven Rising, a local activist group whose demands include an increased voluntary contribution from Yale. Baldwin said that top colleges like Yale are “built on the plunder of their cities,” and he highlighted Yale’s property tax break as a prime example.

Daniel HoSang is professor of Ethnicity, Race and Migration at Yale and a founding member of the Anti-Racist Teaching and Learning Collaborative. He, Blatteau, and Wilbur Cross counselur Mia Cormulada helped me understand the complex structure that determines public school funding, which in turn determines teacher salaries. School funding is allocated at a few levels: first, the city of New Haven determines its annual budget, which includes all of the money that will be used for municipal services in the city. This money comes primarily from property taxes (New Haven’s city assessor, Alex Pullen, did not respond to questions about local funding, which accounts for 58.8 percent of total school funding).

Blatteau added, ‘Yale could really right the wrongs of the historic underfunding of public schools that they have contributed to by taking up so much untaxed property.’

Funding from property taxes does not include money from Yale’s voluntary contribution to the city, which was $23.2 million this year. In 2019, activists in New Haven Rising estimated that Yale would have paid $146,079,896 if its property was taxed as private, 40 percent of the $364,659,346 total public school budget for New Haven that year. Yale’s property holdings in New Haven are increasing every year.

The district gets a small amount of funding–approximately 4 percent in 2020–from the federal government, and the city also gets 37.3 percent of school funding from the state, including money from the Payment in Lieu of Taxes (PILOT) program. The PILOT program gives $90 million in state funding to New Haven to make up for property tax revenue lost because of the city’s large swaths of untaxed property, mostly owned by Yale and Yale New Haven Health. When it comes to Yale’s tax break, this still leaves about $56 million unaccounted for.

Baldwin likened Yale’s tax break to a subsidy that New Haven grants the University each year. When discussing his work with New Haven Rising, Baldwin said, “We want to create policies that induce schools like Yale to be better neighbors.” Blatteau added, “Yale could really right the wrongs of the historic underfunding of public schools that they have contributed to by taking up so much untaxed property.”

Lauren Zucker, Yale’s associate cice resident for New Haven Affairs and University Properties, responded to questions about Yale’s relationship with New Haven in an email: “Yale is proud of its commitment to our home city…the University pays approximately $5 million in property taxes…making Yale among the top three real estate taxpayers in New Haven.” She also emphasized Yale’s cultural contributions to the city, including the University’s Pathways to Science and Pathways to Arts and Humanities programs for New Haven Public School students and Yale’s public museums.

Zucker cited Yale’s recent “historic increase” in voluntary payments to the city, and this year’s $23.2 million contribution. $23.2 million is 15.7 percent of what Yale would pay if its buildings were taxed like private property, according to the 2019 calculations from New Haven Rising cited earlier. Yale’s voluntary contribution still leaves New Haven about $33 million short in property tax revenue.

HoSang added that Yale is not entirely to blame for the harms its untaxed property has wrought on the city. “After all, Yale didn’t author the laws that keep it from paying taxes,” he said. Yale’s status as a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization means that the school is exempt from all taxes on educational property buildings where instruction takes place.

Adding up the money that he spent on books, paper, pencils, markers, craft supplies, and toys demonstrating mathematical concepts, Jett estimated that he spent close to $4,000 on supplies for his classroom this summer.

New Haven Mayor Justin Elicker acknowledged that there is much work to be done to secure adequate funding for public schools, but he said, “We’re seeing both [Yale and the state of Connecticut] take significant steps to address these problems.” Elicker attributed the lack of money for schools to Connecticut counties’ overreliance on city-limited property tax revenue. Property taxes from suburbs and rural areas around New Haven don’t contribute to the city’s revenue. In contrast, Elicker said that other states distribute funding by county, spreading property tax revenue more evenly. New Haven schools would be better funded if the city adopted this system. Still, in Elicker’s view, “the city of New Haven works very hard with very limited resources to support funding for our public schools.”

Even within the district, however, funding is unequally distributed. Jett told me that the Wexler Grant Community school, a mile away from his school between Dixwell Avenue and Canal Street, has two sixth-grade classrooms and twenty-three sixth graders. In smaller settings, teachers can work with each student to meet their needs. The school district’s spokesperson, Justin Harmon, explained how funding is allocated in an email: “Neighborhood schools vary in enrollments as the population around them swells or declines,” he said. “Wexler is in a period of decline. Over time, the district makes staffing and program adjustments in an effort to rebalance the distribution of students and teachers from school to school.” Blatteau maintains that the public school deficit is an illusion: “If schools were a genuine priority,” she said, “the city would find the money.”

If Jett worked in Norwalk, a majority white town with a median household income of $89,486, he’d be making $64,355, according to a salary comparison chart prepared by the New Haven teacher’s union. If he worked thirty minutes away in Westport, a city that is 86.5 percent white and where the median household income is $222,375, he’d make $77,721. In New Haven, where the median household income is $44,507, he makes only $50,440. A portion of Jett’s modest paycheck goes back into his classroom.

To make up for the things his school can’t buy, Jett keeps his classroom stocked by spending his own money. While we were on the phone, Jett pulled up his Amazon purchase history for the last few months, going back to just before the school year started. Adding up the money that he spent on books, paper, pencils, markers, craft supplies, and toys demonstrating mathematical concepts, Jett estimated that he spent close to $4,000 on supplies for his classroom this summer. What the school is able to provide often arrives after the year has started. Teachers who didn’t make similar purchases sometimes begin the year without books. Baumann has experienced these delays, and now buys most of the materials needed for experiments with his own money. All of the teachers I interviewed said they spend some of their own money on classroom supplies, but amounts ranged from a few hundred dollars to Jett’s $4,000. Still, they choose to stay.

When asked if he has considered leaving the district, Baumann said, “I think about it every day.” He knows several teachers who have left just this year. Still, he plans to stay for the next year and a half until he retires: “I…honestly enjoy the eighth-grade team teachers that I’m working with, and I’m probably staying here more for them than for myself or the kids right now.” .

Blatteau said, “Teachers who switch districts love New Haven, but I don’t blame them.”

Comulada agreed.“People need to feed their families, Maybe [leaving] is in their self-care bucket,” she said, acknowledging also that pay across districts “isn’t an even-steven.”

Those teachers who do stay in New Haven remain excited about the district’s potential, and Blatteau said that “this isn’t a crisis without an answer.” The union’s current leadership is advocating for the things rank-and-file teachers want, like smaller class sizes and pay that adjusts to the rising cost of living. In preparation for the election, candidates—all of whom are teachers themselves—worked to increase member engagement in the union, responding to criticisms that there wasn’t enough information available about union activity.

Though he acknowledges that pay and conditions are better at other schools, Jett said, “New Haven is one of the only districts in Connecticut where kids’ and families’ voices are heard, where we’re really trying to fix these problems.” Where other districts promised inclusion but often fell short, in New Haven, “everyone’s doing their best to get kids up to where they need to be.” Still, as Blatteau and her colleagues in the union understand, teaching in New Haven is unsustainable for many teachers.

Things are looking up, though. In November, the city’s Board of Education approved a new teacher contract that will incrementally increase salaries over three years, according to the New Haven Register. In July of 2023, wages will increase 5.9 percent, then 4.9 percent the year after, and 3.9 percent the year after that. By the 2025-26 school year, the starting salary will be $51,421, compared to the current starting salary of $45,457. It’s an overdue improvement, but it might still not be enough.

“Teachers are the most unappreciated and undercompensated [workers],” said Boroski. What’s more, New Haven teachers advocate for their students far beyond the classroom. Comulada recounted two trips to Massachusetts that she organized in 2019, rallying students and fellow teachers to support a student who had been detained by ICE.

Students leave Augusta Lewis Troup at 2:50. Under the hum of fluorescent lights, Jett stows the markers and crayons, sorts early-reader books and chapter books into their separate bins, and reorganizes math manipulatives. He keeps the supplies his paycheck paid for in good shape. A mile away at the Cooperative Arts and Humanities High school, Boroski and Wetmore do their ritual clean-up as well: Wetmore puts away all of her art supplies so that a health teacher can use the room the following morning, while Boroski rolls up the projector screen that he bought for his room.

—Caroline Reed is a junior in Saybrook College.