Domingo Medina, owner and founder of Peels & Wheels Composting, surveys the heap of food waste before him. Over a thousand pounds of rejected leftovers are spread in a neat rectangle at his feet, the sweet smell of decay punching through the winter chill. His son, Noah, shoos his dog away from a banana peel. One employee scours the pile for still-edible melons and potatoes to take home. Another wades into the garbage, picking out stray pieces of plastic and compost bin liners.

Medina grabs a shovel to start turning the pile as he tells me about his composting setup.

“It’s all human-scale,” he says. “It doesn’t require any machinery, just labor force.”

Medina is the brains and one-sixth of the brawn behind Peels & Wheels, New Haven’s bike-based composting service. For $7.50 per pickup, Medina and his five employees will collect your food scraps and pedal them to a small facility by the Mill River where orange rinds and eggshells slowly turn back into soil for local farms and gardens. Since its founding in 2014, Peels & Wheels has diverted over one hundred and ninety thousand pounds of food waste.

I joined Medina for his Monday pickup route on a blustery morning in December. It took a while for him to confirm our meeting point: “My references are trees, doors, corners, not numbers,” he told me.

His process, though, he knows by heart. He coasts into each customer’s driveway, eyes peeled for the little green bin left on the porch or by the dumpster. He weighs the bucket with a portable scale, spins the top off with a practiced ease, and heaves its contents into one of the large black bins on his trailer, smacking the base to dislodge tenacious scraps. And then he bikes away to his next destination, his trailer fourteen or so pounds heavier.

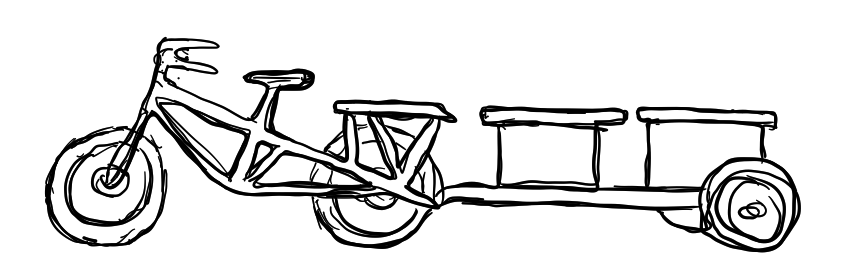

Medina rides a beast of a bicycle: bright orange with an electric assist, a heavy gray trailer, and tires as thick as my forearm. My gray road bike looks puny by comparison. Although Medina was dragging three hundred pounds of garbage, I found myself racing to keep up as I followed him up Canner and down Orange, stopping at three consecutive houses on Whitney Avenue.

Our route reflected the business’s limited clientele. Peels & Wheels only accepts customers in East Rock, Prospect Hill, Wooster Square, Downtown New Haven, and Westville, plus Spring Glen and Whitneyville in Hamden—an eight mile radius covering some of the wealthiest parts of the region. The collection area doesn’t include the lower-income neighborhoods of Fair Haven, although that’s where the compost is processed, or Newhallville, although it’s next to Prospect Hill.

lot of Pheonix Press near the Mill River. Photo by Sadie Bograd.

Medina says he worries about these inequalities, but sees them as the inherent limitations of running a business. It’s not that he doesn’t want to serve more neighborhoods, but that there aren’t enough people requesting his services. Weekly collection costs $30 a month (although about twenty off-campus Yale students get subsidized pickups through the Yale Student Environmental Coalition). Peels & Wheels is funded by its customers, so its customers are mostly people with funds to spare.

“I needed to do something that could pay for itself. I worked a long, long time for not-for-profits,” he told me. “It required me to write grants and to chase the money, and I got tired of it…I’m just not willing to get into boards, and meeting every month, and trying to convince people. My time of convincing is done. For me, it’s about doing.”

Employee Austin Larkin takes a similar perspective. I chat with him while we hack discarded vegetables into pieces, increasing their surface area so they decompose faster. Larkin describes himself as a former “guerrilla composter” who used to bury his food waste in backyards and parks before he discovered Peels & Wheels.

“It felt very logical and also radical,” Larkin says as he jabs a hoe into a particularly sturdy carrot. “Obviously it’s not enough, but it’s also better than nothing. It’s what’s possible right now. And it’s not about finding an ideal, it’s about progress.”

Progress, though, might be difficult without more institutional support. Two years ago, New Haven’s Food System Policy Division received a $90,000 USDA grant, which it used to improve community garden compost systems and start community composting working groups. But due to bureaucratic challenges, the Division failed to find city-owned land where they could start another food waste diversion site. Instead, they used the money to expand Common Ground High School’s compost facility (which Medina helped establish).

In general, local efforts at food waste management are “a little fragmented” and limited by budgetary constraints, according to Deborah Greig, Common Ground’s Farm Director. There are a handful of independent initiatives: in addition to Peels & Wheels, many restaurants contract with the Hartford-based scrap collector Blue Earth Compost, while Yale sends its dining hall discards to an anaerobic digestion facility in Southington. But there’s no citywide compost infrastructure, and no organizations devoted to helping interested residents develop composting skills.

“You need to have municipal-level compost. It almost doesn’t matter that there’s micro-haulers out there,” Greig said. “I think it’s impossible to create equity and access in education and composting itself until there’s also a larger effort [by] the city.”

Medina agrees: he notes that Peels & Wheels is New Haven’s main home compost hauler, yet it only serves about five hundred households out of more than fifty thousand in the city. But he insists that a micro-scale approach can work on a municipal level. Most citywide compost systems, he says, rely on massive trucks and process food waste in a central hub. They treat food waste as a “nuisance” to whisk away rather than a valuable good to return to local residents. He would prefer a decentralized network of compost haulers and processors, with programs like Peels & Wheels closing the loop in every zip code.

“Everybody sees my business like something cute,” he said. “But it’s also a demonstration that things can be done differently.”

Although Medina swears his operation is scalable, he is struggling to make it last. Right now, Peels & Wheels operates rent-free from the parking lot of sustainable printing company Phoenix Press, sweeping stray bits of food from the asphalt at the end of each processing session. Local nonprofit New Haven Farms—which has since merged with the New Haven Land Trust to become Gather New Haven—grows crops in a small plot beneath the press’ wind turbines, and Medina founded Peels & Wheels so that they could have free compost processed on site. But Phoenix Press’ owners are selling, and Medina has yet to find a new location.

Medina is not a melancholy man—fist bumps are his preferred farewell gesture—but as he ponders this dilemma, he turns pensive. Expanding the city’s compost systems requires broader concern about food waste. But how do you get people to stop making their garbage someone else’s problem—to stop “pushing the wrinkle,” as Medina puts it?

He takes heart that he is providing a valuable service for his community. Peels & Wheels started, according to college freshman Noah, as “a notepad with five clients” and “a bunch of little containers all around the house.” Over the last nine years, his dad’s company has kept one hundred and ninety thousand pounds of food waste out of incinerators and created nearly sixteen thousand metric yards of soil-enriching compost.

And it doesn’t hurt that subscribers tend to be effusive in their gratitude.

“I tried [composting with] worms and unfortunately I filled my house with bugs and so Domingo’s service was a godsend when I learned about it,” Virginia Chapman, a Peels & Wheels customer and Director of Yale’s Office of Sustainability, said in an email. “I love the low carbon footprint (the wheels), the garden it was supporting, and the compost I get back every year for my garden.”

Besides, the job stays interesting. Most of what ends up in the compost bins is fairly standard—chopped vegetables, stale bread, the accidental piece of silverware. But when I ask Medina about the strangest thing he’s seen in a compost bin, he has an answer prepared.

“I honestly thought there was a woman that was trying to compost her husband,” Medina said.

Strands of hair and fingernail clippings started showing up in her compost bin. Then shirts, then trousers.

Medina never saw any human limbs—and, as far as he knows, there were none to be disposed of. But if it weren’t aiding and abetting a murder, he says Peels & Wheels could have composted them.

“We’ll take anything that’s organic…animal or plant-based.”

– Sadie Bograd is a sophomore in Davenport College