Anna Tender was “already very out” as bisexual when she came to Yale in 2018. Her first week on campus, she followed the stream of nervous first years to the fraternity houses on High Street, towards what seemed to be the archetypal college party: red Solo cups, a watered-down keg, and unremarkable music shaking the sticky walls. As she relaxed into the party, she began to dance with a girl next to her, letting her hands rest easily on her waist. Half-drunk, and thinking of very little except enjoying the night, Anna kissed her.

“Huge mistake,” she says of the public kiss now. A man leaned in and asked, leering, “Can I join?” They broke apart. Over the next few days, she found that the news of the kiss had spread through her residential college, without her knowledge or consent. People she barely knew “freaked out” at the fact that Anna, with her long hair and more femme style of dress, hadn’t been what they expected of her. A carefree moment turned into a public dissection of her sexuality. “After that,” she says about the party, “I was like, ‘Oh, okay. I get it. This is not a space for me.’”

She stopped going to frat parties, and started befriending more queer women: people she met in classes, members of her modern dance group, mutual friends, and hookups. Somebody added her to an email list for an organization called “Sappho,” an informal social group that hosted a semesterly party for queer women and nonbinary people. They promised a night out free from the anxiety that Anna felt at frats. Her sophomore year, she arrived at a “Euphoria”-themed party in the basement of the women’s rugby team apartment on Elm Street. This was no Bud Light-ruled rager: attendees adorned themselves with glitter, sipping colorful, intricate cocktails made by student bartender Lauren Lee. She had already started to attend “smaller, more intimate” parties dominated by queer women, from wine nights hosted by girlfriends of friends to a set of lingerie parties hosted by an all-woman society. But Sappho was the largest gathering of queer women she’d seen in one space.

At “the Gay Ivy,” where, according to a Wall Street Journal article published in 1987, at least “one in four” students are some kind of gay, lesbian social life is hardly an underground niche. But over the decades, Yale’s lesbians and queer women have wrestled with how to carve out a social life that is safe but still exciting.

1970s: Yalesbians begins

In September 1975, a record twelve women attended a meeting of the Gay Alliance at Yale (GAY), a mostly male discussion and advocacy group. It was the height of the lesbian feminist movement, and some young lesbians were growing frustrated with what they saw as the patriarchal focus of gay activism across the United States. Four years before, the Yale Women’s Center was founded as a space for undergraduate women to gather. In 1970, the activist Del Martin published an essay, “If That’s All There Is” in the lesbian review The Ladder, where she condemned gay rights organizations as sexist. Lesbians—growing doubly frustrated by the homophobia they experienced from straight women and the marginalization within gay spaces—felt they needed a space to breathe.

Two lesbian undergraduates, the out-and-proud Tara Ayres and a partially anonymous woman identified only as “Sarah” by The Yale Daily News, formed a Yale-registered sister group to GAY known as “Yalesbians.” On a balmy September night, twenty lesbians and self-identified “straight woman” allies met for the first time at the GAY room in Hendrie Hall. They adopted the format of “consciousness-raising circles,” open feminist discussions where women connected wider political issues to the struggles of their everyday lives. The organization also co-ran multiple projects with GAY, including a telephone counseling service and a weekly radio hour called “Come Out Tonight.”

Yale’s Weekly Bulletin and Calendar initially ignored requests to publicize Yalesbians’ weekly meetings. After a few weeks, they finally responded and began to reluctantly spread the word. Through word of mouth and print ads, membership grew to about one hundred people. As co-founder, Tara noted Yalesbians’ membership was a low estimate of the true proportion of lesbians on campus, arguing in a 1977 report to the Yale Corporation that the average gay woman at Yale “is probably not vocally a lesbian, and is afraid to be identified as such.”

Lesbians—growing doubly frustrated by the homophobia they experienced from straight women and the marginalization within gay spaces—felt they needed a space to breathe.

On New Year’s Eve in 1976, a fire destroyed part of Hendrie Hall, burning out the room where Yalesbians and GAY met, as well as the headquarters of the service frat Alpha Psi Omega. While the frat was re-housed almost immediately, the administration dodged Ayres’ inquiries about finding a space for Yalesbians for over a month. In late February, Tara and GAY member Jack Winkler were finally able to march up to the Associate Dean of Student Affairs’ office to secure a new space in Bingham.

Off campus, meanwhile, many lesbians could still find social and political community in the lesbian feminist scene in New Haven. “By the end of the [1970s],” Yale alum and former Yale LGBTQ history professor George Chauncey wrote in The Yale Alumni Magazine, “New Haven was home to an extraordinarily vibrant and complex women’s culture and lesbian feminist movement: the Feminist Union; feminist bookstores, women’s health centers, self-defense classes.” While Yale lesbians (and Yalesbians) found political homes in New Haven’s more radical feminist scene, they often came cleaved closer to campus to party.

1980s: Lesbians after hours

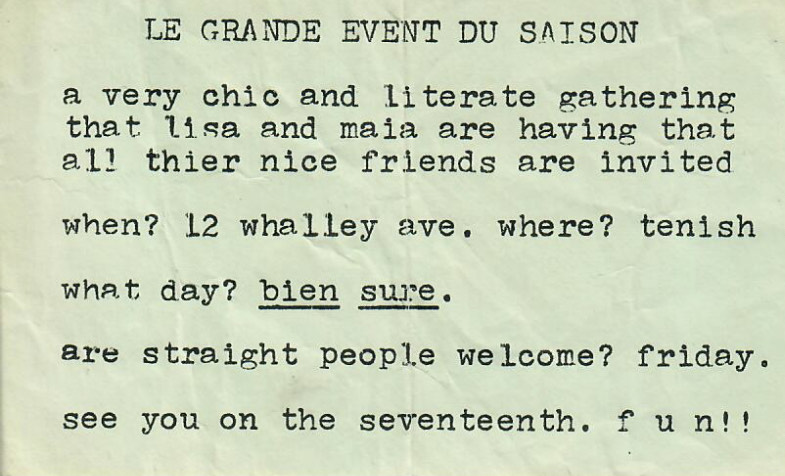

By the late nineteen-seventies and early nineteen-eighties, separatism was no longer the word of the day. Maia Ettinger, a former official leader of Yalesbians, told me that by the nineteen-eighties, the gay “scene” was more multiracial and cross-gender than the “pretty white” nineteen-seventies separatist world. She moved off-campus to 12 Whalley Avenue, where she lived with fellow Yale gays Judith Rodenbeck, Lisa Kennedy, and the late Donald Suggs, who later became known as a Black gay activist and journalist during his postgraduate life in New York City. While Maia was a leader of on-campus lesbian life at weekly Yalesbian meetings, the household threw after-hours parties that brought campus gays together on more relaxed terms.

Rather than being exclusively lesbian, the household “invited everyone cool, which was cool with us,” explains Maia. Though the parties skewed gay, they allowed proud lesbians and straight lefties alike to dance to Boy George, Annie Lennox, and Prince, who were bringing queer aesthetics and sensibilities into popular music for what felt like the first time.

Listening to Maia sketch out her gay world, I was enthralled by the vibrancy of her social and political life. I also started to wonder how my life would have unfolded on the gay campus of 1982. I certainly wouldn’t have identified as nonbinary the way I do today—Maia confirms that while “androgyny” was the word of the day, and something many campus lesbians pursued, the language just “wasn’t available” to identify outside of womanhood.

Romantic and sexual relationships flourished—most queer women that Maia knew had both casual encounters and long-term girlfriends. On nights out at several gay off-campus apartments, open lesbians made out with the girls who had attended weekday Yalesbians meetings as “straight allies.” The mood was both celebratory and anxious, and increased visibility came at a cost. In 1982, Yale’s LGBT Co-operative held the first Gay and Lesbian Awareness Days (GLAD), which culminated in an on-campus dance for which the administration gave permission. Maia remembers a group of football players had overheard that a girl they knew, someone they certainly didn’t think was gay, was attending. One athlete stood outside the door, trying to intimidate her, and Maia “just hauled off and punched him in the eye.” She was proud to see him later that week with a black eye. The gays danced on.

Hostility continued to accumulate. In February 1984, the senior class threw a party at what is now Grace Hopper College, where the 17-year-old daughter of a Yale faculty member was kicked in the stomach by male students. The men taunted the girl, and the female friends she was dancing with, with chants of “Lesbos!” Susan Arkun, a Yale College student who was verbally harassed at the event, explained to the News that in social spaces she was often met with derision owing to her short dyed hair. “I wish those lesbians would leave so we could tap the keg,” she overheard once. Strangers shouted “Yalesbians!” at her on the street.

Maia freely accepts that in the face of these explosions of homophobia, some of her football player-punching bravado was bluster. She wishes the gay communities on campus had the language at the time to articulate “how frightened we actually were.” At 18 or 19, she explains, “maybe you access anger more easily than you access your own vulnerability.” Parties are a good way to deflect from the fact that it is often difficult to be young and gay and alive.

Sappho comes out

Yalesbians faded, let down by a quick student body turnover and a lack of institutional memory. The group’s archives were smaller and more informal than a lot of other, larger, official student orgs. Leadership changed hands, over and over again. By the time the third millennium rolled around, Yalesbians’ weekly, Wednesday meetings had stopped. I combed through campus newspaper archives to find some concrete reason for the organization’s dissolution, but came up with nothing. The last mention of the group I could find came in 1995, when the News advertised a regular Yalesbians meeting as part of “Sexuality Awareness Week.”

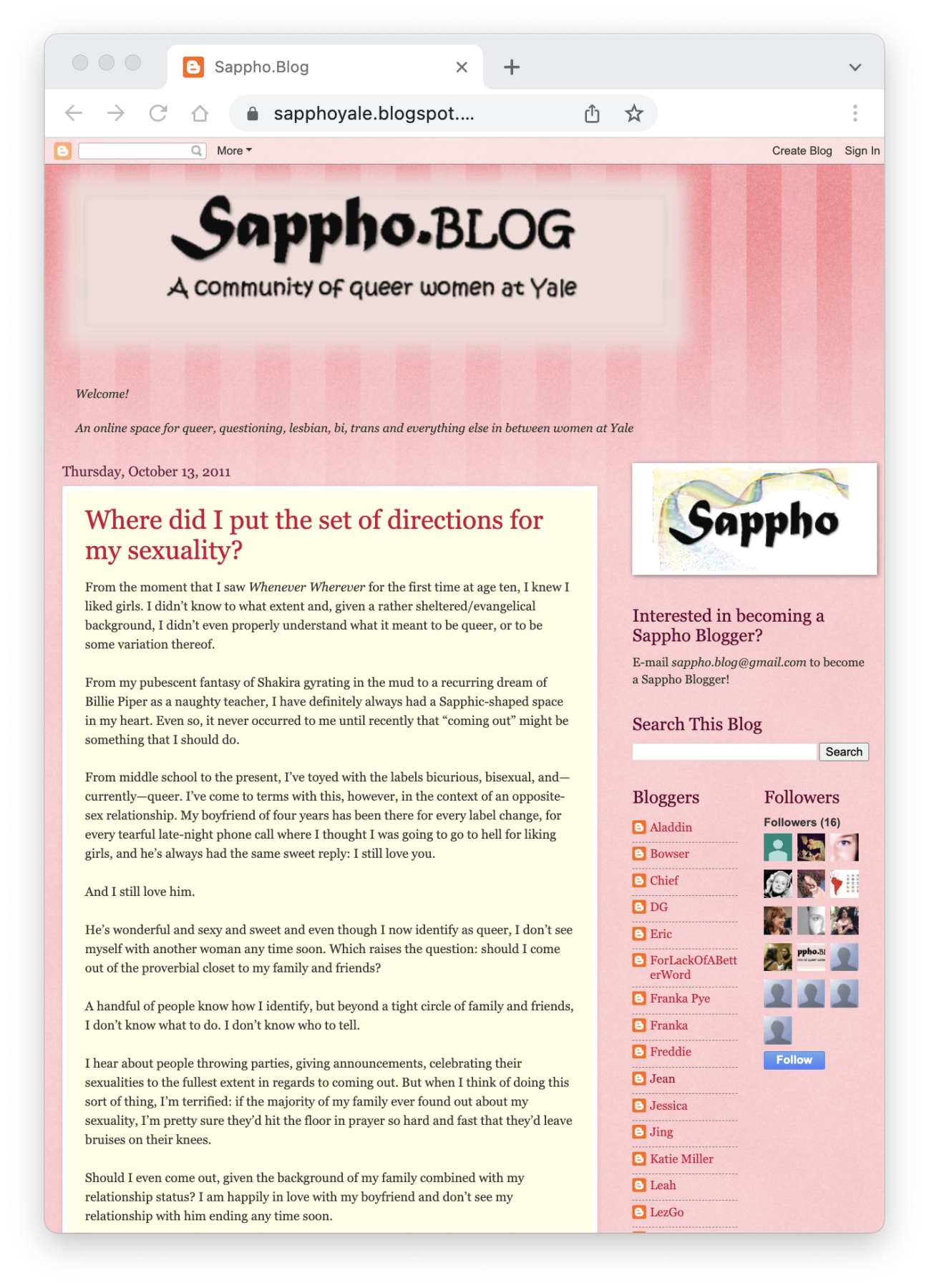

But lesbians, specifically, still wanted a space to come together. Sappho, named after the Greek poetess who gave us the word “lesbian,” was founded by an unknown group of queer women in 2004. Unlike Yalesbians, who were a registered student organization receiving Yale funding, Sappho began—and remained—an informal social collective. Sticking true to Yalesbians’ 1979 declaration to “never again turn to the YDN” to publicize their work, Sappho in 2010 started to reach other on-campus queers in the most 2010 of ways: a blog.

on campus to stay connected amid the emerging digital age.

On sapphoyale.blogspot.com, “queer, questioning, lesbian, bi, trans, and everything else in between women at Yale” could post, anonymously or not, about anything that came to mind. In the style of full-on early 2010s hyper-enthusiasm, they gushed about their sexual awakenings (“I LOVE TOPPING…Eeeeee.”), brought gay political news to the blogosphere (“Yay, queer people can now visit thier [sic] partners in hospitals just like married people!”), and rejoiced over queer pop culture (“how awesome was glee in so many ways? way awesome.”) The blog encompassed the complexities of lesbian social life in the emerging digital age. On the one hand, queer women on campus could now stay connected to each other at all times, even in physical isolation. Dozens of posts popped up over summer and winter breaks, lamenting homophobic households and celebrating hometown pride parades. But in some ways, with the arrival of the internet, lesbian spaces were also in the process of becoming more isolated, more dispersed. Websites like Tumblr, which flourished in the early 2010s, allowed younger queer people to “come out” under digital aliases, while remaining closeted in their day-to-day life, not taking the risk (and thrill) of venturing into physical queer spaces. Lesbians could raise their consciousness from the comfort of their home, without looking another queer in the eye.

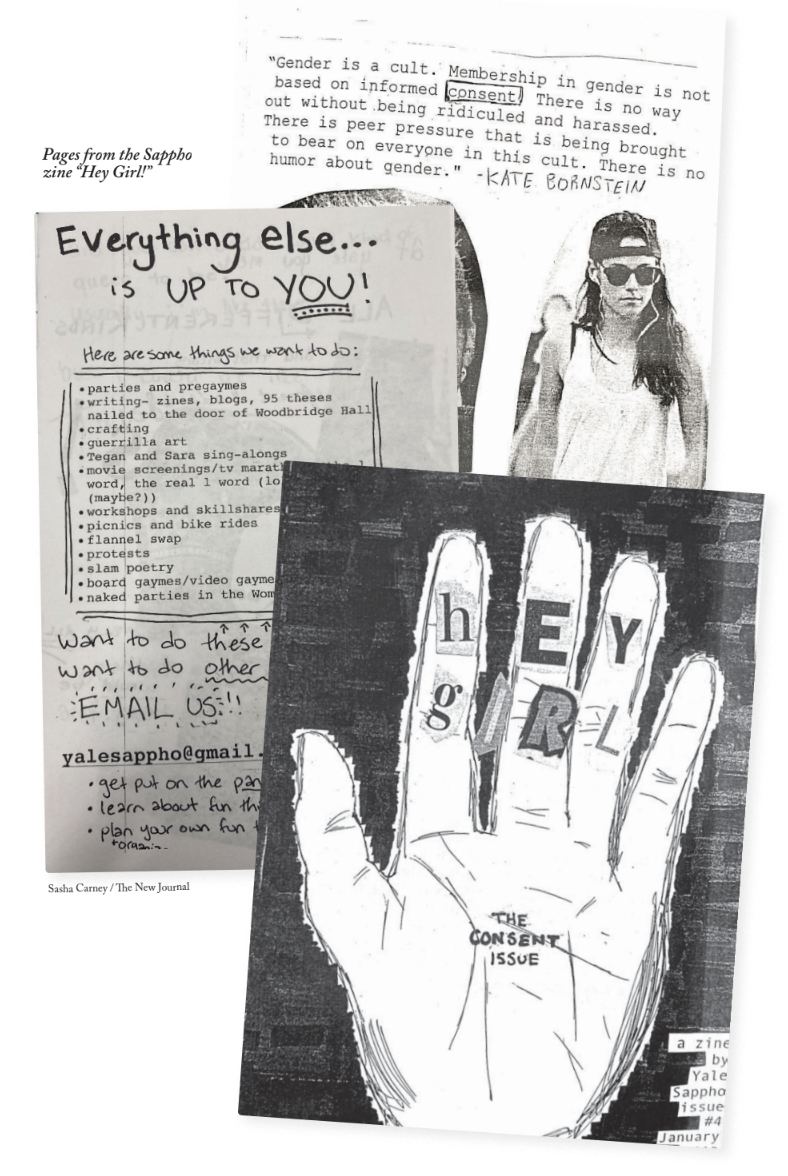

The blog only lasted a year before being replaced in September 2012 by a series of zines called “Hey Girl!” Perhaps Sappho’s new leadership, tiring of the dispersed nature of the digital, wanted to throw it back to the heyday of analog feminism. The DIY-style zines, frequently thrown together over the span of one night, were a deliberate aesthetic homage to the anarchist, punk, and Riot Grrrl subcultures of the nineteen-eighties and nineteen-nineties. They set out an ambitious agenda for what Sappho would bring to the “queer ladies” of Yale, including guerilla art, skillshares, protests, “parties and pregaymes,” and—supposedly—naked parties in the Yale Women’s Center. The zine was earnest, funny, and pro-Beyonce. One full-page spread of collages and hand-scrawled slogans encouraged readers to “queer up Yale ” in any way they knew how. “GET OUT THERE! YOU DO YOU!” the caption blared over a drawing of a Venus symbol, a printed-out picture of the Hulk, and an invitation for lesbians everywhere to “make friends” and “make enemies.”

The zine folded after four issues. The idea of “parties and pregaymes” stuck around. Though it’s incredibly difficult to track down the “official” emergence of Sappho parties, in 2014, a Silliman student named Zoe heard, through Facebook groups and word of mouth, about a semesterly party for sapphic people only. The series of Sappho parties, which was funded entirely by the friend groups of juniors who put them on, was “passed down” each year to a new friend group of queer women deemed sufficiently cool, with enough off-campus space to host. “Everyone seemed to know about it, but I can’t tell you how,” she recalls.

This sense of uncertainty and anonymity, which persisted throughout Sappho’s existence, is a kind of double-edged sword: these social spaces are at once unconstrained by official channels and institutional funding, and difficult to historicize or pin down. Of course, “everyone” can also never entirely encompass “everyone.” Though Sappho invitations were entirely open, most knowledge of the parties, like in Maia’s day, boiled down to who already knew who.

As sophomores, Zoe and her roommates were selected to throw next year’s Sappho parties, but with few guidelines and no funding by the women who came before them. With money they had saved from campus jobs and donations from attendees, they put on a couple successful events where “people were definitely there to hook up.” Zoe recalled these parties as “more mixed-race and more genderfruity” than most other campus parties, and found herself encountering butchness as a possibility she could pursue for the first time. Attendees felt at ease picking up women in ways they didn’t elsewhere on campus—ways Anna didn’t at the frat party her first year. The next year, Zoe and her friends passed the baton to another Silliman friend group. She confesses that she has no idea if they carried it on.

They did, although some people grew frustrated with the slowness of the parties’ semesterly format. “I think we need more parties to cruise at and have sex at,” recent Yale alumnus Mia Arias Tsang told me bluntly. She spent most of her time on campus surrounded by other queer women of color through her work at Broad Recognition, a campus feminist publication. Though she was already in those environments in her day-to-day life, she was looking for more explicitly sexual and romantic lesbian spaces after-hours. She remembers her disappointment at missing a Sappho party in 2017 where attendees reportedly did body shots. Anna expressed to me that although she wasn’t seeking sex at the parties, being in multiple monogamous relationships through her time at Yale, she enjoyed their distinct atmosphere, at once both electric and celebratory.

When Mia did attend the fall 2019 Sappho party in the rugby basement, she felt a huge “pressure to fuck” owing to how infrequent and unpredictable the parties were. She felt that these opportunities were somewhat scarce, and felt anxious about not taking full advantage of them. “I went with friends who all peeled off and found other people to have sex with,” she recalls. She adds that she was pleasantly surprised by the amount of lesbians of color there, but “at any Yale space,” she acknowledges, “as a queer [Woman of Color], if you’re trying to get laid, it’s going to be hard.” Still, she came away grateful for the experience, and excited for next semester. But before the next party, Covid hit.

Today: Everyone is gay

As of 2023, “lesbian life” or “queer women’s life” spills out into much of everyday life at Yale. With outness not only encouraged at Yale, but essentially the default in vast swathes of the campus’ academic and social world, many lesbians don’t have to look for “lesbian groups” or “gay issues” to find the comfort and community they seek. “It felt like my life was inherently a queer space in a way I never experienced before college,” Mia explains. Many other queer students echoed this sentiment, feeling that while they variously enjoyed Sappho parties, they didn’t feel the need to attend them to find sex, love, or friendship.

“I don’t think I hang out with anyone who isn’t queer,” Ava Dadvand, an Iranian trans lesbian, decided after thinking for a moment. She finds most of her queer friends through Beyond the Binary, an official on-campus trans and nonbinary social group, as well as through social media, friends of her partner, and other mutual friends. A lot of it is incidental. On an increasingly “out” campus, you can meet other lesbians and sapphic people with ease from a class seminar to the line for lunch. Add in the queer-centric social spaces of Yale Twitter, as well as the opportunities for casual sex and romance from dating apps, and you’re giving Sappho-specific bulletins like Sappho.blog and Hey Girl! a run for their money.

The definition of a “lesbian social space” is also increasingly changing as the idea of “lesbianism” does. While the Sappho of the early 2010s nominally included trans women in the labeling of their organization (if not in the content of their blogs and zines), the language of the world of “lesbians” has become more complex and gender-diverse as medical and social transition become increasingly possible. Last semester, I had top surgery through Yale Health. Newly healed this semester, I feel more comfortable at parties and excited to dance, but more anxious in things closer to “women’s spaces.” I jump back at the thought of throwing someone off in a bathroom or changing room. I believe “lesbian spaces” can, and should, include people like me, but I don’t always feel at ease in those dominated by cisgender, gender-conforming women. The concept of a “lesbian-only” or “woman-only” space can sometimes be code for “cis women-only,” something Maia worried about when I described Sappho parties to her over the phone. “The parties aren’t trans-exclusionary, right?” she asked sharply. I assured her that they weren’t, at least not in their advertising. But it’s certainly possible that some trans people stay away.

Ava is perfectly happy finding a home in what she calls “dyke spaces,” but also notes that she’s found it a lot easier since she had bottom surgery last summer. She concedes that this sounds “bioessentialist” of her, overly focused on genitalia as the site of sexuality. But, after all, she explains, our society is bioessentialist. “It’s drilled into our heads, for better or for worse, that lesbianism is associated with pussy.”

While campus “lesbian life” has become more trans, Sappho parties have arguably become less so. After the onset of Covid-19, what events have popped up feel distinctly lackluster. Lily, a senior who started attending Sappho events in 2022, describes the two parties they stopped by simply as “boring.” The music was soft, the drinks were sparse, and the energy was conversational—more of an “affinity group” than a party space. After recently beginning to present more masculine, they were acutely aware that the people they met at a fall 2022 Sappho party were “almost all femmes, and pretty white too.” They headed home early.

Attendance at these last two parties was small, something exemplified by the relative lack of undergraduate knowledge about Sappho. When I asked her about Sappho parties, Ava, who arrived at Yale in 2021, confessed “I don’t know what that is.” The same things that make Sappho exciting, flexible, and cool—the lack of Yale institutional ties or funding, the informality of leadership, word of mouth —also make the whole operation hard to maintain. By the time someone intending to throw a Sappho party has the means to bring their idea to fruition, they may have already graduated. Not to mention, there’s no unified vision behind what makes a Sappho party “good.”

I, for one, don’t want the Sappho party tradition to die out. Lesbian nightlife on campus—the kinds experienced by Ettinger in the nineteen-eighties, or what Anna reveled in as a first-year—is facing a number of challenges. The difficulties of resurrecting marginalized party spaces after Covid, the hesitancy around where exactly to define “lesbianism” or “queer womanhood,” and the uncertainty around whether exclusively gay social life even needs its own space on such a strongly queer campus, all seem to lead people to pause before they send out an invitation to a naked party in the Women’s Centre. I say, there’s value in taking the extra, deliberate effort: to carve out a semesterly space, to reach queer women beyond your social group, to confront the contradictions of a lesbian night out. Let the gays dance on.

—Sasha Carney is a senior in Silliman College.