Rolling hills. A long pasture of highway. Cars grazing in the distance.

The view from the classroom at Danbury Correctional Facility could be idyllic enough for portraiture—if one leaves out the chain link fence.

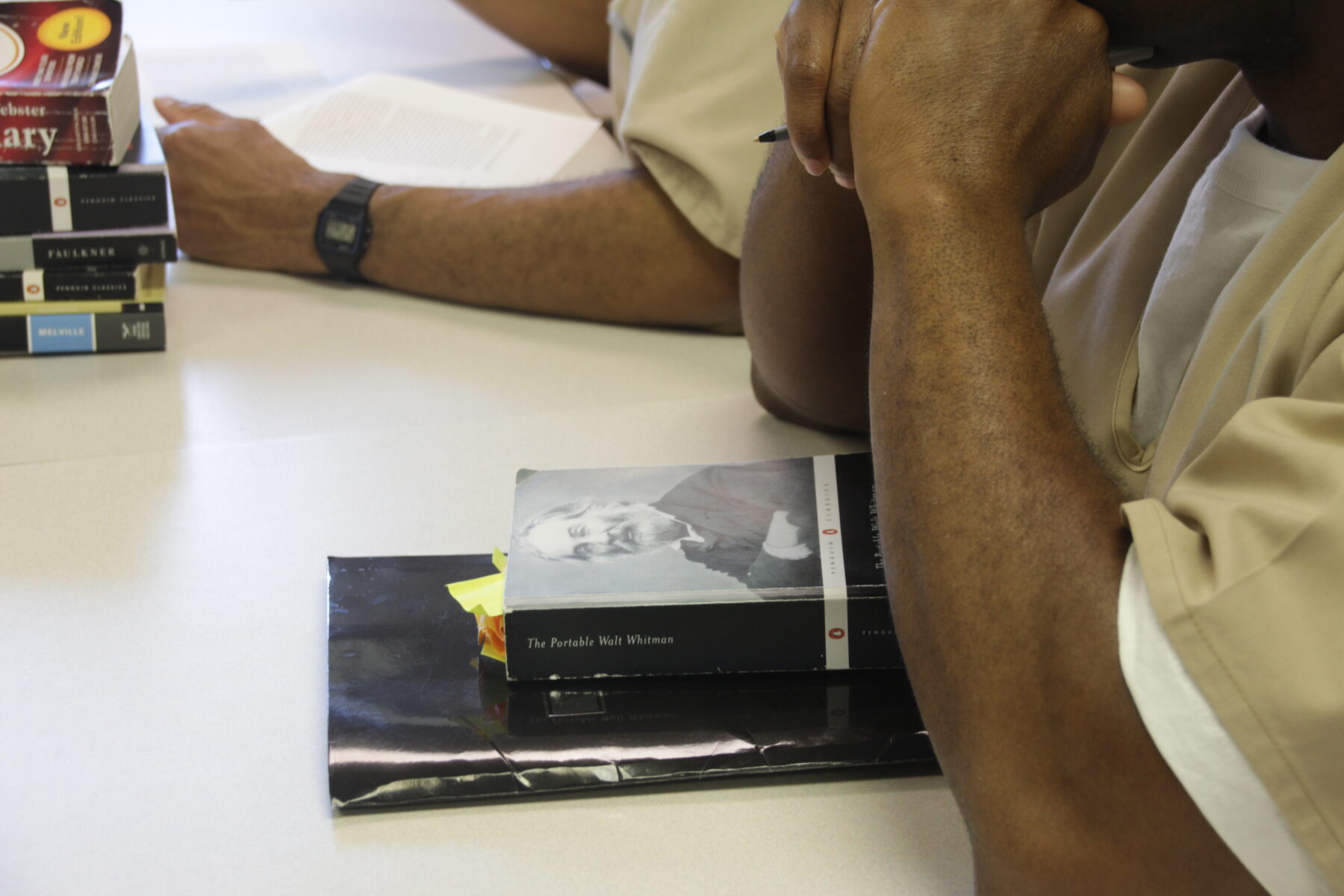

Jonathan Herrera Soto YSA ’23, a Teaching Fellow in the Yale School of Art’s Art and Social Justice Initiative, spent the slippery months of mid-summer driving up a jagged path to a small parking lot in western Connecticut.

Lugging art supplies from his trunk, Herrera Soto would enter the prison for a security screening reminiscent of the TSA’s. At times, guards turned materials away, forcing him to return crates of styrofoam back to his car and improvise lesson plans without them.

“I know I’m not supposed to bring in, like, hazardous contraband, but I don’t really know what contraband is,” he told me. “I’m also not imaginative enough to see how some of these things could be used as weapons.”

In his application for the fellowship, Herrera Soto wrote about his older brother who was incarcerated. During visits, a glass window stood between them. The separation was part of what brought him to the craft of drawing. The “technique of seeing and looking” became a way to better understand his memories. Yet, a summer teaching in prison challenged him to ask: in the art of rendition, is the truth only what appears?

“Part of [one] assignment was to draw outside,” he tells me, describing students’ apprehension about including the fence. “As your instructor, I want to say that it’s your choice, if you’re going to use the chain link fence as evidence of what you actually see. But also…omission is a creative decision to maybe get at a deeper truth or more of the truth. And I had the students [say] to me, ‘Alright, from here on out, no more fences.’”

BEGINNINGS

In the summer he taught at Danbury, Hererra Soto joined a host of Yale and University of New Haven faculty who teach in the Yale Prison Education Initiative—a Dwight Hall program founded in 2016 by Yale alumna Zelda Roland ’08, GSAS ’16. Each semester, the YPEI hosts approximately thirteen classes at MacDougall Walker Correctional Institution and Danbury Federal Correctional Institution, with between seven to fifteen students in each course. The YPEI is a member of the Bard Prison Initiative’s nationwide Consortium for the Liberal Arts in Prison, which runs programs from fifteen universities across ten states.

The partnership between universities and prisons can occupy a tenuous space, particularly given the difficulties plaguing both institutions.

With soaring fees, post-graduate employment in limbo, and faculty bogged down by bureaucratic bloat, media and academics have claimed that the University is in crisis. The Prison, too, has been decried for its inhumane conditions, and the disproportionate representation of low-income BIPOC in its surging populations. For two institutions that have accumulated a barrage of negative media coverage over the past few decades, prison education programs present a unique opportunity to change the narrative.

From a PR perspective, it’s not difficult to see the benefits of hosting a program like the YPEI for an institution like Yale. Last year’s graduation alone turned up more than sixty hits from a quick Google search, with nationwide media outlets such as AP News, PBS, and NBC picking up the story. The Yale name finds itself front and center in this coverage, with headlines including “The Jail to Yale Journey” and “Seven Prisoners Earn College Degrees from Top World University.”

“As you can probably tell,” Roland tells me, “the University is celebrating this program in a big way. It’s taking a lot of credit for what we’re doing. And what we’re hoping for is that it will lead to better investment and buy-in.”

When Roland initially pitched the program to the Connecticut Department of Corrections, the Commissioner stopped her mid-spiel: he’d been waiting for someone at Yale to propose this idea for years.

“For me, the prison system in Connecticut always wanted us inside it,” Roland explains. “Yale was the holdup.”

Ultimately, while the YPEI bears the Yale name, degrees are awarded by the University of New Haven—a decision informed in part by logistics (Yale doesn’t offer Associate Degrees), and in part by exclusivity.

“There’s always a tacit awareness that the selective nature of elite universities in the United States necessarily means that only a few can have something that’s valuable,” says Peter Crumlish, Director of Dwight Hall. Extending that education to more people—particularly incarcerated people—breaks down Yale’s value system. “And you hear people saying, well, what about people who aren’t incarcerated who are deserving? Shouldn’t we start with them?”

This question of merit—who deserves an education, particularly a Yale education—clouds the rollout of the program. For faculty and students within the YPEI, higher education is a means of reclaiming inmates’ humanity in prisons and paving a better life post-release. Yet, resources and funding constraints mean that only a select few can access this legitimizing force. In a setting where release isn’t guaranteed, performance post-prison still seems to be the prevailing metric that matters. This begs the question: In between the Prison and the University, is personhood something you have to prove?

LIBERATING THE MIND

For students at MacDougall-Walker Correctional Institution, the journey to class is a taxing one.

Much of students’ days—twenty hours if the prison is in lockdown—are spent in cells. When it’s time for class, they embark down a long gray “hallway of hopelessness,” according to Marcus Harvin, an alumnus of the YPEI (’23) and a current College-to-Career Fellow. He described how the trek is a double-edged sword—“a sign of hope for the inmate population but a sign of ridicule for the Corrections Officers.”

Indeed, despite supportive prisons from the YPEI’s administrative perspective, all five incarcerated students I spoke with described a degree of hostility from guards across prisons. Though some COs displayed interest in students’ coursework, many firmly espoused the belief that incarcerated people did not deserve an education, much less one from an institution like Yale.

“Some will even be bold enough to say to each other when a group of students are coming by, ‘Oh, we got to pay X amount of dollars [for college], all they got to do is come to prison’,” says Harvin. “You got to get through a lot of hostility, to get to, let’s say for vernacular’s sake, History.”

History is held in a seminar room at the end of the hall. With a round table, chairs, and a window, it could resemble any classroom at Yale. But instead of lush courtyards and blue skies, students gaze out at the prison block, where other inmates walk to and from class. Harvin describes it as an “educational warehouse.”

Part of the violence of a prison is its mundanity, says Hector Rodriguez, an alumnus of the Bard Prison Initiative and a current College-to-Career Fellow at the YPEI.

“I will look into the yard and people go in circles like zombies,” he told me “That’s your routine for every day of the sentence. You’re doing the same thing.”

For Herrera Soto, proposing assignments for Basic Drawing meant finding ways to fight this mundanity. He suggested that students use abstraction—rendering an image with scribbles. “It’s great because it’s not really your bunk or the concrete hallway…but [still what] we’re trying to learn, which is value,” he said.

The classroom itself, for many students, is a departure from the oppressive routine of the prison.

“You’re planning something and you’re performing or you’re writing and that brings you to another world,” says Elizabeth Hinton, a History professor at Yale and in the YPEI. “It’s important to provide people—[where] the purpose of prison is to remind them where they are in the world—to be able to transcend that.”

James Jeter, an alumnus of the Wesleyan Center for Prison Education and the Founder of the Dwight Hall Civic Allyship Initiative, labels professors as “idealists,” facilitating a space where “for the first time…[students] get to actually have an experience outside of being an inmate.”

“It’s like the best part of the day that anybody in such a situation could have,” says Harvin. “Because you don’t only get educated. You get community, communication, camaraderie. And that’s something that prison lacks because it’s such an independent process…It’s like a facade or dream, right? …But like, we can’t really survive by ourselves.”

Cultivating this community of optimism is not without its challenges. For Paul North, Co-Faculty Director of the YPEI, teaching a class called Non-Cynical Social Thought required an exercise in imagination.

“We looked for a way to think about society that wasn’t cynical,” North said. “What does it mean to look for utopian moments? And students are resistant at first.”

For their final projects, students were tasked with analyzing an intentional community in history. One decided to focus on Black Wall Street, a prosperous area in Tulsa, Oklahoma heralded by Black agriculturists in the early twentieth century. It was eventually the site of a devastating massacre. For their final projects, students resurrected the community, acting out a day on Black Wall Street.

Hinton describes how in her African American Literature class, many students were able to name—for the first time—the structural forces of race, class, and gender that played a role in their imprisonment.

“This is essentially the essence of the value of a liberal arts education,” says North, “liberating your mind.”

And yet, liberation in a prison setting is always limited. Eventually, class ends, and students, armed with the academic tools to interrogate their oppression, must still embark back down the “hallway of hopelessness.”

“Of course, it’s cool to be on Instagram for the Governor. It’s cool to be on Yale’s Instagram…But it sucks to have to go back to a cell after you learn all of this stuff,” says Harvin. “After you’ve just been told by one of the most brilliant people in your field that you are brilliant yourself. But you’re still behind bars.”

In a prison setting, where students tolerate harassment to go to class, Jeter says inmates must be wary of conflating studenthood with personhood.

“You can’t get roped into believing that something is worth more than your freedom,” says Jeter. “That this version of your humanity is worth more than your overall humanity. Nothing is worth more than your personhood.”

NOT AN EDUCATIONAL UTOPIA

For many, college in prison isn’t just about education; it’s about the future it offers post-release.

“A lot of times, we’re not really looking at recidivism as a metric of success in higher education. That’s not important to us,” says Roland. “But to sell the program to the facilities, they want to know that higher education is impactful for recidivism, or that it’s having these different metrics, which it does.”

At the Danbury location, Site Director Tracy Westmoreland mentions a new Ward who really “sees the value” in the program: “If the students are gonna go back to the community, they need education, they need to be able to get a job. Otherwise, it’s just a vicious cycle.”

The philosophy that helps pitch prison education programs, then, stands on two fronts. One, that attending college in prison will behaviorally reform inmates, decreasing recidivism rates and increasing public safety. Two, that education programs will make inmates more productive in the workforce, becoming high-functioning and contributing members of society.

While these are the principles that help get prison education programs through the door, they often come with fraught implications.

Hinton argues in her lecture “Second Chances: Redemption and Reentry after Prison” that reliance on recidivism as a metric further reinforces the idea that education is a privilege. “It is necessary to redefine education from social utility,” Hinton says, “from its purpose being to train people to develop useful skills that will allow them to succeed in a global capitalist market, to individual utility.”

This, Hinton tells me, looks like a world where education is afforded to incarcerated students simply so they can “understand the world better, expand their horizons”—without any expectation of capital return.

Yet, for some students, education is a means to an end. Reentry often means low-wage, labor-intensive jobs at warehouses or construction sites. Having a degree opens up an entirely different trajectory—the ability to make a living.

Rodriguez describes how in the Bard Prison Initiative, some inmates would apply year after year: “Every time they keep trying…because they see people go home and have good jobs.”

“Wesleyan’s motto was ‘Education for the sake of education.’ No one in that program was looking to be educated for the sake of education,” says Jeter. “It’s impossible to be real, because learning has been so commodified in America…Men and women want to get out. They want to get better. They want redemption. They want to prove something. So this isn’t for the sake of education.”

Ultimately, inmates have lives they lead outside of prison, and many have hopes of one day making their way back to the places and people they love. In one of Herrera Soto’s assignments, where students were tasked with drawing portraits, many turned to the only references they had—photos of their children.

“That was particularly hard because I wasn’t expecting the effect,” Herrera Soto says. “There’s nothing that prepared me for going to check on people’s homework and then they’re sharing their stories of their kids.”

For one student, prison education was a way of reconnecting with her daughter who was finishing high school. “She’s participating in the YPEI to show her daughter,” Herrera Soto told me, “…if your mom can do it, then it’s never too late.”

THE PRISON-TO-COLLEGE PIPELINE

“[Yale] owns New Haven,” says Harvin. “Yeah. That’s how I felt. That they own it. And maybe that they owed something to it?”

Historically, Yale has a long record of perpetuating racial and economic inequality in New Haven, purchasing large swaths of land, over-policing, and limiting local hires—all while evading property taxes. The majority of students at MacDougall-Walker Correctional Institution are from New Haven, Hartford, and Bridgeport, directly residing in spaces where Yale is implicated.

“Therefore,” says Hinton, “it should be part of Yale’s responsibility to share its resources with students.”

Currently, Yale’s investment in the YPEI primarily comes through administrative support, such as faculty and indirect contributions. Roland stresses the importance of these resources, yet the University’s direct financial commitment to the program is “such a low number” that she doesn’t share it. “We raise nearly the entire budget for this program through private grants and individual donations,” she says. “And it’s all funds that are raised not through Yale, but through Dwight Hall.”

Real buy-in from Yale, Hinton says, would require an expansion of resources and a shift in its educational mission.

In the past, courses in prison counted as overload for faculty—classes they taught on the YPEI’s payroll—in addition to a full schedule at Yale. A recent administrative win means that now, professors can count one credit taught in prison as part of their normal workload, covered on the University’s dime. In Hinton’s view, this policy should apply to all course credits.

What does this mean for the University’s educational goals on campus?

Rather than a “side project,” Hinton says Yale should include educating incarcerated students in its primary mission, thus addressing inequalities that are “studied so deeply [at the University] but that Yale as an institution has helped to create.” This could look like a degree awarded by Yale itself—something that the YPEI administrators I spoke with characterized both as an improbable pipe dream and an ultimate goal.

Hinton calls this the “Prison-to-College Pipeline,” a radical reimagining of prisons as a space for “mass education,” and a world where the transition to college post-release is seamless, with institutions like Yale taking the lead in facilitating degrees for students upon reentry.

This is work that the YPEI has already begun to undertake. The College-to-Career Fellowship offers one to two years of funded “professional development, career exploration, and mentorship opportunities” for formerly incarcerated alumni of any prison education program. Students pursue their academic interests, drawing from the wealth of resources that Yale offers—professors, libraries, mentorship. Roland calls it a “Fulbright for formerly incarcerated students.”

Marisol Garcia, a College-to-Career Fellow and a graduate of Wesleyan’s Center for Prison Education (CPE), is using the Fellowship to supplement her exploration of teaching and policy, while also pursuing her law degree at the University of Vermont.

“Even let’s say people who are not formerly incarcerated,” Garcia said. “[To] have an opportunity for a two-year fellowship at a university as large as Yale, with their resources, and their networks, and the different opportunities?”

Initially, Garcia’s many commitments dissuaded her from taking on a full-time fellowship, but a mentor told her, “You would give up an opportunity that would take you multiple lifetimes to be able to even explore Yale.”

A SELECT FEW

Hearing about the application process for the YPEI, I was surprised by its extensive rigor, some components even exceeding what was required for my own application to Yale.

After an initial information session, the YPEI invites interested students to submit a written component, consisting of three to four short answer questions and a longer essay. Next, students complete a timed essay in response to a prompt—often quotes from literary icons. A committee of faculty and formerly incarcerated staff read their applications, looking primarily for the “desire to engage with questions.” Some are then invited to participate in a mock Socratic seminar. Finally, a select group of students are interviewed. In 2018, out of nearly six hundred applicants to the first YPEI class, twelve were granted a spot, amounting to an acceptance rate of 2 percent.

It follows then, that for participants in the YPEI, being a student is a matter of prestige, replicating Yale’s real-world hierarchy and the hostility its exclusivity creates.

“People in the community college programs will often subordinate themselves to someone in the Yale program. ‘I’m not as smart as you Yale dudes,’” Harvin says. “So what it does is, it kind of gives the people in that program, rightfully so, some level of esteem amongst their peers. It takes a lot to get into the program, even more to stay in the program, and not just to stay, but to excel in the program.”

Yet, in a setting where those I spoke with described professors as the only ones who treat them like humans, what does it mean that this program is only accessible to a select few, and that “it takes a lot” to excel within it?

“Everyone should understand that education is always valuable,” says Ernest Francis, an alumnus of the YPEI (‘18). “Most of us wouldn’t be here if we had education. Right, you will make better choices…An educated person doesn’t commit crime because you understand the reality, right?”

Indeed, while prison education is often touted as a “second chance,” Hinton argues in her lecture that “most incarcerated people never had a first chance” at school. With over-policing in historically under-resourced districts, many Black and brown youth are funneled into places like MacDougall by the school-to-prison pipeline. Prison education, then, is the righting of a wrong that begins before inmates are even incarcerated.

And it must be treated as such. “Until there’s legislation that says a person has a right to education,” says Francis, “there’s always going to be a small amount.”

In a prison setting, this exclusivity runs the risk of maintaining the carceral system.

“Prisons do just enough to basically say we’re doing something,” says Francis, “but they don’t want to turn prisons into colleges…It’s in your best interest not to educate everyone because if no one comes back, why would you exist?”

The YPEI must be funded, developed, and nurtured. On this, faculty and students are in overwhelming agreement. If Hinton’s vision comes to pass, prisons will one day be colleges, democratizing education and the humanization that can come with it.

At MacDougall Walker Correctional Institution, Harvin was referred to by a number: 403853.

Today, as I sit in the crowd at Pitts Chapel United Free Will Baptist Church, he is introduced by a Bishop who marvels at how three days after being released from prison, Harvin found himself “on top of a hill at Yale University.” Among the sea of friends and family who have come to see his first sermon, Harvin shouts out one row in particular—his professors at the University of New Haven, where he is now completing his degree.

“I got some good news,” he says. “Number 403853 has passed on.”

The crowd cheers; the organ blares; “It’s your time!” someone shouts. Harvin ends the sermon with a beginning: “Allow me,” he says, “to reintroduce myself.”

ENDINGS

After his summer teaching for the YPEI, Herrera Soto returned to his studio in Erector Square, uncertain about what came next for the lives he briefly encountered.

“Something about leaving always felt hard…Saying bye and then going through a bunch of gates and then you drive away,” Herrera Soto says. “Yeah. It was kind of gnarly.”

Still, part of him was relieved.

“There’s so many contradictions, so many things that get in the way sometimes,” he slows, cars from the street below droning through the silence. “It’s hard to hold the feelings of caring for your students. And then that feeling, sometimes in my body, like you shouldn’t be in here. And I don’t know. I don’t know if I’ve resolved that for myself.”

Sitting on a crate, Herrera Soto’s silver earring catches the abundant light of the studio. It’s a stark contrast to the darkness of the prison he drove to three times a week, in the wet heat of mid-July.

“At Danbury when I taught, all the good and bad was also housed within this feeling of dread of the prison,” he says. “Every minute you’re there, there’s this feeling. Like you can’t leave. Like once you’re in there…You’re in a prison. You can’t just run out the door.”

Before I go, Herrera Soto shows me his students’ drawings. Just one more, he insists, pausing to marvel at each one. It’s a beautiful piece, he affirms. Over and over again: “Like objectively, just looking at, it’s a beautiful drawing.”

For her final project, one student—Felicia—drew a self-portrait. Her inked signature is shadowed by charcoal. She is the focal point of the piece, elevated in a vortex, hair parted by the wind. The floating faces of her classmates flock out from around her. A sea of eyes, they stare at her as we stare at them. We, the viewers, are aliens. And we’re abducting her.

“The fact that she’s bigger or the other people are smaller. It doesn’t necessarily make sense. [But] she’s the most important part,” Herrera Soto says. “When you’re imagining from a different perspective, you’re imagining more of the whole…Which is hard for a student.”

He ponders whether the alien is a metaphor for wanting to escape. I think about wholeness.

“Yeah,” he tells me. “It was hard to leave.”

-Aanika Eragam is a sophomore in Pierson College and an Associate Editor of The New Journal.

Photos Courtesy of Karen Pearson and Zelda Roland.

*Corrections: A previous version of this article incorrectly referred to YPEI alumnus Ernest Francis as Francis Ernest. Additionally, the correct name for Paul North’s class is “Non-Cynical Social Thought,” not “Non-Cynical Socialists.”